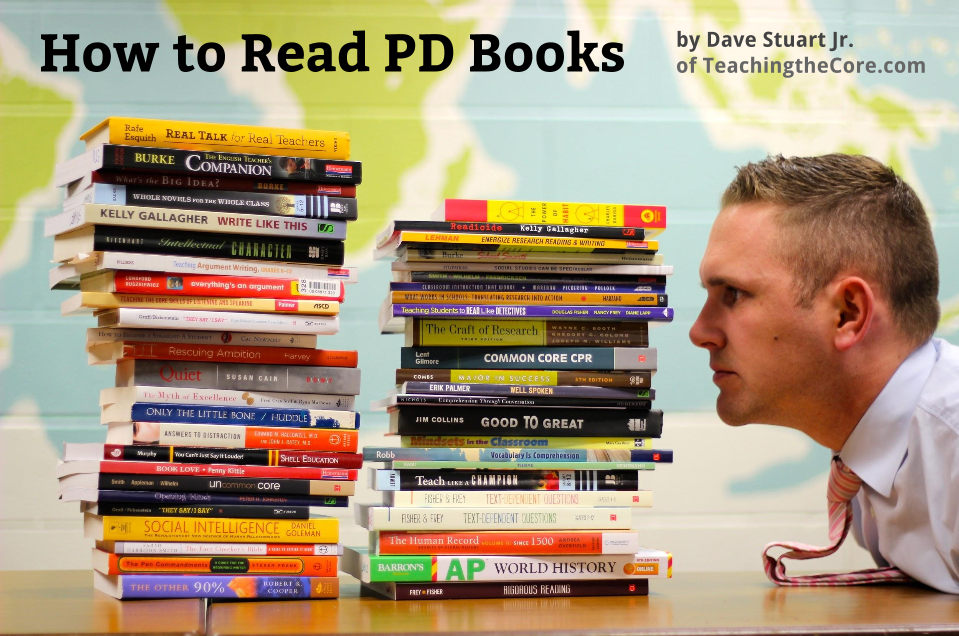

Whether you're a teacher, administrator, instructional coach, central office person, or someone else, I'm guessing you're familiar with the fact that there are a lot more edu-books out there than any of us have time to read.

And their unmanageable quantity is not the only tricky thing about professional development books; they also vary in their utility. Some are immediately useful, superbly organized, and blessedly efficient; others are anecdotal or theoretical or haphazard or verbose.

In this post, I want to help you read professional development books better. I want to do this for a simple reason: reading professional development books, when done smartly, is one of the most cost-effective methods to help us get better at teaching. When reading a PD book is done right, you basically get access to someone like Jim Burke or Kelly Gallagher or Mike Schmoker or Doug Fisher for less than it costs to take a date to the movies.

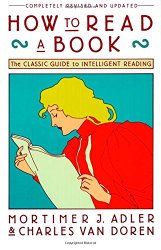

Throughout much of this post, I'm going to draw from Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren's decades-old How to Read a Book, which is securely on my “Top Three Most Important Books I've Read in My Life” list. Why so important, you ask? Because it taught me to read on purpose, and reading has helped me do lots of stuff.

Let's dive into the tips.

1. Accept this truth: there's more than one way to read a book

We've got to get past the idea that reading a book means plowing through from cover to cover.

As an example, one of the top tips I give to folks who buy my book is to not read the whole thing.

This has nothing to do with trying to be humble, either. If the book merited a sit-down read-through for everyone, I'd absolutely advocate for that. Humility isn't about talking yourself down; it's about thinking of others more than yourself.

I give this advice because, for most folks, my book will not be the first thing they've read about the Common Core — therefore it doesn't make sense for them to read through every last standard — but it will probably be one of the more accessible texts on the topic and perhaps the only one that focuses exclusively on the anchor standards rather than diving into grade-specific considerations. In other words, my book helps readers grasp at the big picture — what are these standards aiming at? — and you can get the bulk of that big picture through reading the introductory chapters, the conclusion, and a sampling of the “Why Is This Important?” sections that follow each anchor standard.

And whether you read my book the way I recommend above or through carefully reading each sentence, cover to cover, guess what? I'd say you've read my book — you've just done it in a manner that suits your purposes.

From How to Read a Book:

Many books are hardly worth even skimming; some should be read quickly; and a few should be read at a rate, usually quite slow, that allows for complete comprehension.

It all comes down to what you need from the PD book.

So before doing a full sit-down read through, another type of reading is merited (drum roll please).

2. Read all your PD books inspectionally

From How to Read a Book:

Most people, even many quite good readers, are unaware of the value of inspectional reading. They start a book on page one and plow steadily through it, without even reading the table of contents. They are thus faced with the task of achieving a superficial knowledge of the book at the same time that they are trying to understand it. That compounds the difficulty.

As Adler and Van Doren go on to say, the word superficial often has negative connotations, but it need not be so in the case of inspectional reading. We read inspectionally to answer simple questions, like

- What is this book about?

- What are its parts?

- What problems can it help me solve?

One challenge I'm giving myself this year is to give an inspectional reading to every PD book on my shelf. From then on, I'd like to make a habit of doing this for every additional PD book I get.

But Dave, you say, don't be insane — ain't nobody got time, man. Look at them stacks, brother.

But here's the beauty of inspectional reading: it has a time limit.

To do an inspectional read, give yourself 15, 30, or 60 minutes. With that time, you have a simple goal: get the most out of the book that you can. Through doing this, you will begin to internalize the value of organizational, summary elements found in virtually every PD book, like the intro, the conclusion, the list of graphics, the table of contents, and the index.

From How to Read a Book:

Do not try to understand every word or page of a difficult book the first time through. This is the most important rule of all; it is the essence of inspectional reading. Do not be afraid to be, or to seem to be, superficial. Race through even the hardest book. You will then be prepared to read it well the second time.

Books ideal for an inspectional reading

While every PD book is worth at least a quick inspectional read, there are some that yield inordinate amounts of fruit from quick, superficial readings. These are the kind of books you inspectionally read and then keep on a close shelf for easy reference.

While every PD book is worth at least a quick inspectional read, there are some that yield inordinate amounts of fruit from quick, superficial readings. These are the kind of books you inspectionally read and then keep on a close shelf for easy reference.

Two examples that immediately come to my mind are below.

- Jim Burke's Common Core Companion series (available K-12). I write about the series here.

- Lemov's Teach Like a Champion. Loaded with over 50 techniques, this book is a great example of one ideal for an inspectional read.

3. Stop saying “I could never read a book in 60 minutes”

From How to Read a Book:

There is no single right speed at which you should read; the ability to read at various speeds and to know when each speed is appropriate is the ideal.

Growth mindset is in vogue these days, and yet it's incredibly common, even from some of the most enlightened folks I talk to, to hear this kind of statement: “I'm a slow reader.”

That, my friends, is a textbook example of fixed mindset! Reading is a skill, and like any skill, we can develop it.

Until I was 28 or so I used to say I was a slow reader. And it was true; I was!

But 28 found me with a wife I wanted to still be close to, two tiny kids, a house that needed work, a full-time job that, believe it or not, is rather demanding, and a baby blog I hoped would someday turn into something.

All of this added up to something simple: I no longer had time to accept being a slow reader. Thankfully, it was around that time that I started taking How to Read a Book seriously, so I began simply trying to read faster. I didn't put a lot of pressure on myself, but I did give myself time limits within which to read sections of books (and eventually entire books), and this led to me steadily getting faster as a reader.

I'm not a speed reader yet, but I am quicker than I was two years ago when I started trying to get quicker.

4. Once you've inspectionally read a book, “satisfice”

One of the most valuable concepts I've learned this year is that of satisficing. I learned of it from Eric Barker's blog, and he draws it from Daniel Levitin's The Organized Mind. (One more book on my wish list!)

One of the most valuable concepts I've learned this year is that of satisficing. I learned of it from Eric Barker's blog, and he draws it from Daniel Levitin's The Organized Mind. (One more book on my wish list!)

To satisfice, you seek a solution to a problem that achieves acceptable results, rather than seeking the solution that achieves optimal results. When applied to our PD reading, this means that when we're struggling with using rubrics or keeping a class engaged or helping students read complex texts better (or perhaps instilling in them a love of reading) or getting them speaking better (or with greater social skill), it's often best to use our basic knowledge of the books on our shelves (gained through inspectional reading) to decide which book to pick up and search within to find an answer.

Very, very, very often, I see teachers trying to find optimal solutions when they should instead be seeking solutions that offer acceptable, or improved, results. The implemented partial solution is superior to the non-implemented, I'm-still-looking-for-it perfect solution. There rarely are silver bullets in education.

5. Read a select few of your PD books analytically

From How to Read a Book:

If inspectional reading is the best and most complete reading that is possible given a limited time, then analytical reading is the best and most complete reading that is possible given unlimited time.

Since analytical reading calls for you to read a book the best you can, it's not something you should do with every book. Like Francis Bacon once said, “Some books should be tasted, some devoured, but only a few should be chewed and digested thoroughly.”

When reading a book analytically, here are the questions you're seeking answers to, according to How to Read a Book:

- What is the book about as a whole?

- What is being said in detail, and how?

- Is the book true, in whole or part?

- What of it?

What books are worth an analytical reading?

Here are 12 PD books I recommend analytically reading. If you have more to add, I'd love to have you share them in the comments section below this post.

- UnCommon Core, by Jeffrey Wilhelm, Deborah Appleman, and Michael Smith. They focus on a problematic series of lessons on MLK's “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”and teach us much about teaching as they break these apart.

- Clueless in Academe, by Gerald Graff. His observations and solutions have radically informed what I hope to help my students achieve each year. Jerry and his wife, Cathy Birkenstein, wrote They Say, I Say, a book we reference frequently here at Teaching the Core, after Clueless.

- Book Love, by Penny Kittle. Penny is trying to answer the biggest questions we have as English teachers; I respect her because her answers to the questions aren't static; they are deepening each time I see her talk.

- There Are No Shortcuts, by Rafe Esquith. I owe Rafe for my high expectations for students, and yet I don't always agree with him. This is his earliest book; he's also written Teach Like Your Hair's on Fire and Real Talk for Real Teachers, but I like Shortcuts best.

- Readicide, by Kelly Gallagher. Masterfully short, packed with power. Gallagher is one of the guys who inspired me to get started writing for teachers through this blog.

- Results Now, by Mike Schmoker. Even though it came before Focus, Results Now is a more comprehensive book.

- Well Spoken, by Erik Palmer. The dearth of quality speaking instruction is one of the greatest crimes in education today. Palmer's book is the most helpful corrective. He's written other books, but this remains my favorite.

- English Teacher's Companion (4th Ed.), by Jim Burke. The man is as humble as he is smart. This book almost fell into my inspectional read section, but it belongs here — I don't know how this man puts the entirety of the English Teacher's practice into a single book, but he does.

- How Children Succeed, by Paul Tough. An engrossing look at the birth of the character strengths movement.

- College, Careers, and the Common Core, by David Conley. Conley is the father of the term college and career readiness. I had a hard time choosing which of his books to put on this list, so I'll also say that College Knowledge is sweet, but that I find College, Careers, and the Common Core, his most recent book, more developed and relevant to my school.

- Good to Great, by Jim Collins. It's a business book, but it constantly gets cited by edu-types, especially administrators. And for good reason — while there's a lot of unhelpful “let's think of school's as businesses” rhetoric out there, Collins' findings about great businesses shine a lot of light on some of the sillier things we do in schools. (Hint: the “greats” profiled in the book don't become great through large, sweeping, hypey initiatives.)

- Rigorous Reading, by Doug Fisher and Nancy Frey. I have no clue how these two do it — they write about 14 books per year and all of them seem solid (I have to say seem because I cannot for the life of me keep up with reading them all — seriously, I swear they outsource their entire lives to write like they do). This book is eminently practical.

Not feeling the costs of these books? Have your administrators foot the bill — here's how.

6. Annotate

From How to Read a Book:

If you have the habit of asking a book questions as you read, you are a better reader than if you do not. But… merely asking questions is not enough. You have to try to answer them. And although that could be done, theoretically, in your mind only, it is much easier to do it with a pencil in your hand. The pencil then becomes the sign of your alertness while you read…. Unless you [annotate], you are not likely to do the most efficient kind of reading.

I've written about teaching students to purposefully annotate, but this is all about you, dear educator — not the chillens.

In every conversation about annotation I've ever had with a group of teachers, there's always been at least one person who says that forced annotation frustrates him/her because he/she has never annotated in the past and finds it artificial and pointless.

Here's how Adler and Van Doren respond to adults who view annotating as pointless.

From How to Read a Book:

Why is marking a book indispensable to reading it? First, it keeps you awake — not merely conscious, but wide awake. Second, reading, if it is active, is thinking, and thinking tends to express itself in words, spoken or written. The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks. Third, writing your reactions down helps you to remember the thoughts of the author.

If you own the thing, read it with a pen in hand.

7. Use what you read

A mentor of mine used to lead a men's Bible study on Tuesday nights in Baltimore, and at that Bible study he'd have us literally write a simple sentence on the edges of our Bibles. The phrase was this: This book is not boring if you obey it.

Now, whether you agree with that statement or not, I've found that it's pretty powerful to apply this thinking to the PD books we read — with slight modifications. So I literally will sometimes write on the edges of my PD books, “This book is not boring if you apply it.” (Obey felt a bit strong.)

When reading a PD book becomes trying something new in the classroom, we really start to learn.

In summary

To read PD books better, remember:

1. Accept that there's more than one way to read a book

2. Read all your PD books inspectionally

3. Have a growth mindset about your reading speed

4. Think “satisfice”

5. Read a select few books analytically

6. Annotate

7. Apply what you read

Got more tips? Other books recommendations? Experiences to share? Let's hear it in the comments.

And please, apply something from this post!

Mary Lou says

Again, very helpful! Thanks so much!!

davestuartjr says

So glad to hear it, Mary Lou — thank you 🙂

Angeline says

Once my son came along, I found myself reading in different ways too. Your posting perfectly describes the reading modes that I find myself shifting in and out of as I read any book.

davestuartjr says

Gotta love the impetus that those kids give us to work smarter, not harder!

JimW says

I get so much better use out of my PD books once I started annotating them. Aside from the usual underline/star system, I also have a special symbol I put in the margins if it’s an idea I can use right away in class. I draw a little light bulb in the margin (for “idea”). When I’m skimming at a later time, looking for something to do the next day, that symbol usually helps me find the most practical passages.

davestuartjr says

Jim, love it — simple and actionable. I put an empty checkbox in the margin when it’s something I want to do or try.

Thank you for sharing!

VrKimmel says

Thank you for this insightful post. I must admit that through the years, I thought I was cheating when I read inspectionally. As an educator, wasn’t I suppose to read every word of every professional book I picked up? The 7 steps you share are spot on for making the most of the abundance of great PD books that educational professionals should read.

I must say that in my role as a district facilitator/coach, I found something you said to be incredibly compelling. “Very, very, very often, I see teachers trying to find optimal solutions when they should instead be seeking solutions that offer acceptable, or improved, results. The implemented partial solution is superior to the non-implemented, I’m-still-looking-for-it perfect solution. There rarely are silver bullets in education.”

Now I understand why teachers/administrators are many times reluctant to apply what we know to be powerful practices based on research. In their desire to look for the “sliver bullet”, They are led to pass on solutions that will provide improved results. Knowing this, will affect my work. Thank you, thank you once again.

davestuartjr says

I appreciate you sharing that that line resonated with you — and my mind is a little blown hearing it explained in your words. Thank you!

philosophyiseverybodysbusiness says

Hello,

We are a not-for-profit educational organization founded by Mortimer Adler and we have recently made an exciting discovery—three years after writing the wonderfully expanded third edition of How to Read a Book, Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren made a series of thirteen 14-minute videos—lively discussing the art of reading. The videos were produced by Encyclopaedia Britannica. For reasons unknown, sometime after their original publication, these videos were lost.

Three hours with Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren, lively discussing the art of reading on one DVD. A must for all readers, libraries and classroom teaching the art of reading.

I cannot exaggerate how instructive these programs are—we are so sure that you will agree, if you are not completely satisfied, we will refund your donation.

Please go here to see a clip and learn more:

http://www.thegreatideas.org/HowToReadABook.htm

ISBN: 978-1-61535-311-8

Thank you,

Max Weismann, Co-founder with Dr. Adler

davestuartjr says

Max, this is very cool — I am sorry that I am just now reading this! I just ordered the videos — I’m excited to learn from them!

Melissa Balk, librarian says

That’s why it’s great if you have access to ebooks (our regional libraries have 24/7 access) to collections like ASCD, so you can “inspectionally” search for a section. Love this post

davestuartjr says

Melissa, I would LOVE that.

Doug Stark says

Is one of the strategies to let your friend Dave read all of the books for you?

davestuartjr says

That is a great strategy, Doug. #8 — I forgot to include it.

Kim says

Hmm…just realizing I’ve had a fixed mindset about my reading pace. I’ve always been the person to say “I’m a slow reader” and as a result, I’ve lost entire years in grad school and first year teaching by not reading books of my choice. Well now I know, I’m free from the chains of my fixed thinking! This is my third time reading this post and today was the day it finally clicked!

davestuartjr says

Kim, third time is the charm 🙂 Thank you for giving this article so much of your time; I hope the “click” pays off for you and your work.