In my book These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most (2018), I introduced the Five Key Beliefs as a methodology for analyzing and doing something about student motivation problems. Due to the need to treat more than just the Five Key Beliefs in the book (after all, they are just one of the “six things” the book is about), I kept the chapter as brief as I could in hopes of writing a book-level treatment of the Five Key Beliefs in the future. In 2023, that book-level treatment was published as The Will to Learn: Cultivating Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own.

In this article, I'll give you everything you need to know to get started with the Five Key Beliefs. For a fuller treatment, check out my books through the links above.

What Are the Five Key Beliefs?

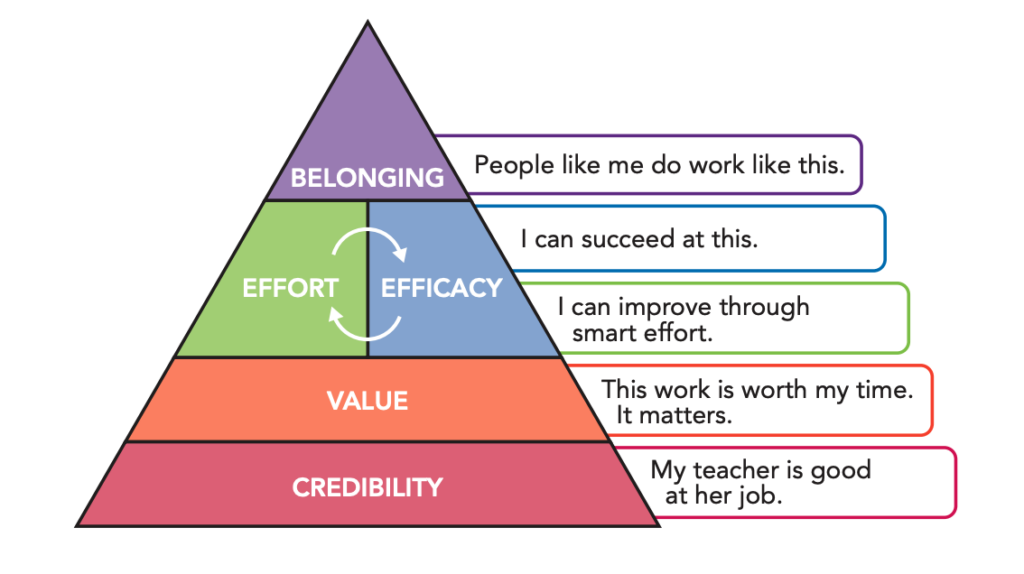

Credibility, Value, Effort, Efficacy, and Belonging — these are the roots of student motivation, which presents itself as care-driven, learning-conducive behaviors. They explain why markedly different-looking classrooms can have such similar motivational dynamics. What I mean is, let's say you were to find me a dozen classrooms sprinkled throughout the world. In each of these classrooms, students do work with care and are growing in mastery, but that's all they have in common. Otherwise, they're completely different — different pedagogies, different physical spaces, different subjects, different student ability levels, different demographics, different teacher personalities.

Despite their important differences, at the root of all these spaces, you'll see the same thing again and again: thousands of contextual signals pointing student hearts toward the Five Key Beliefs.

When the heart is all set, the mind is primed for development. And understanding the Five Key Beliefs can help you get the heart set in all kinds of settings.

The Five Key Beliefs pave the path to the head. Because the path to the head, it turns out, is through the heart.

(For a quick video summary of the Five Key Beliefs, see this video.)

Let's look at each belief briefly, and I'll link you to a page where you can learn lots more about how it works and what to do to influence it.

- Credibility: My teacher is good at her job. Though it sounds too simple and hokey to be true, John Hattie finds in his meta-analysis that classrooms in which the students believe in their teacher are more than twice as productive as classrooms in which students do not. The key here is sending intentional and consistent signals to our students that we care, that we're competent, and that we're passionate.

- For a detailed treatment of Credibility, see pp. 33-100 in The Will to Learn, pp. 28-38 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

- Value: This work is worth my time. It matters. It's not enough to have a belief in my teacher (Credibility); I must also believe in the work I am doing. Is it worth all the work? The key here is creating a counterculture in our classrooms, one in which both the teacher and the students believe and can articulate why the work of learning in this subject is important to one's real life.

- For a detailed treatment of Value, see pp. 101-166 in The Will to Learn, pp. 51-58 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

- Effort and Efficacy: I can improve through smart effort. I can succeed at this. These two are tied together. I believe hard work will pay off and that I can get better as I go; I work hard and with increasing effectiveness; my hard work yields growth (i.e., success); I now more strongly believe hard work will pay off. The key here is intervening at the points in the cycle where Effort and Efficacy beliefs are broken.

- For a detailed treatment of Effort and Efficacy, see pp. 167-218 in The Will to Learn, pp. 44-51 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

- Belonging: People like me do work like this. I fit here. Belonging is all about identity-context fit. It answers the question, “Does who I am fit with what I am being asked to do or where I'm at or who I'm with right now?”

- For a detailed treatment of Value, see pp. 219-242 in The Will to Learn, pp. 39-44 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

For a look at my earlier summaries of the Five Key Beliefs, see these articles:

- Five Key Beliefs: The Source of Abbe's Superpowers (2018)

- The Five Key Beliefs that Motivate Student Writers (2018)

- The Five Key Beliefs: More than Band-aids (2018)

- What's a “Minimum Viable Understanding” of the Five Key Beliefs? (2022)

- The Five Key Beliefs in Five-ish Minutes (2023)

How Do the Five Key Beliefs Work?

Though theoretical considerations like I'm about to share can seem far removed from day-to-day classroom practice, I find that these understandings are what power my ability to accurately understand how the Five Key Beliefs are helping or harming a given student's motivation.

That said, here are five critical qualities of the Five Key Beliefs (for a detailed treatment of these, see Chapter 2 of The Will to Learn):

- Quality 1: The Five Key Beliefs are knowledge held in the will. A belief is something beneath cognition. It's mundane. It's the stuff of the everyday — the stuff you don't even think about. Instead, you just know it, and you act on it, and you do so again and again and again and again, without thinking. Belief is the bedrock of assumption. And from this foundation of beliefs, we enact our lives. In other words, it's a kind of knowledge we hold in our will, not our head. And so you come to your beliefs primarily through experience, not merely from being intellectually convinced.

- To further unpack this quality, see pp. 13-17 of The Will to Learn or this article or this one.

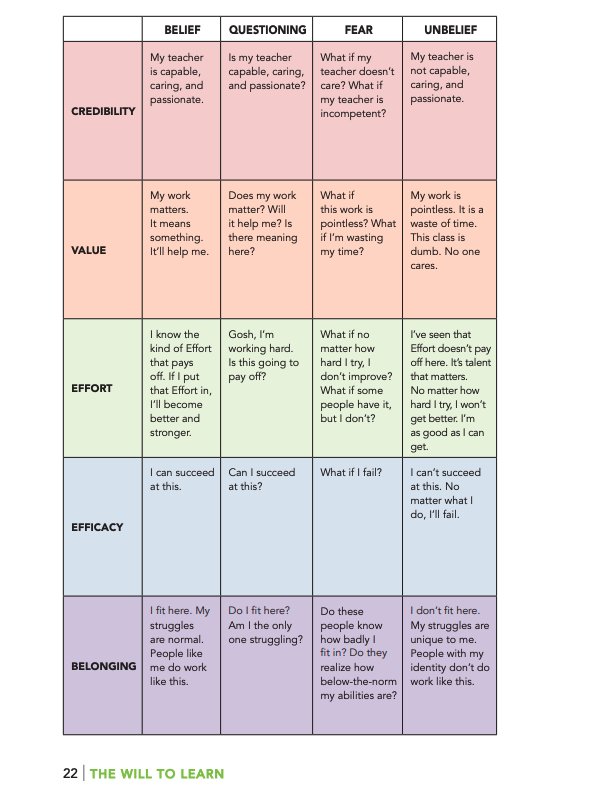

- Quality 2: All of the Five Key Beliefs exist on a spectrum in the heart of each student. The heart of every student in your classroom and school can be found somewhere on the rows in the grid below.

It's common for teachers to say things like, “Well, that student is just not motivated.” The spectrum idea teaches us that it's not that simple, which is really good news. It's more accurate to say, “At present, the student doesn't seem to believe that:

- Math matters (Value).

- She can improve her understanding of science (Effort).

- Ms. Smith is a good computer science teacher (Credibility).

This is what I mean when I say that the Five Key Beliefs methodology can help us analyze student motivation more effectively than we currently tend to. Accurate analysis enables effective action.

To further unpack this quality, see pp. 17-23 of The Will to Learn.

- Quality 3: The Five Key Beliefs are hierarchically interrelated. When I was first developing the Five Key Beliefs methodology, I had five beliefs in an unordered list. Eventually, I began to see how some beliefs form the foundation for others. When you look at the Five Key Beliefs pyramid (the first graphic in this article), you have to build from the bottom. Focus first on cultivating Credibility, then Value, then Effort and Efficacy, and finally Belonging. (Many teachers do it the opposite way and begin with Belonging; this is problematic, as I explain in this article.) This “build from the bottom” approach helps when you're feeling overwhelmed by the Five Key Beliefs methodology. What I always tell teachers who are getting started is focus on Credibility. It's especially malleable, it's the most within your control, and it's the point of best leverage from which to influence the other beliefs. With that said, once you get a handle on all the beliefs, you're going after all of them all the time in the context of the mastery work you're doing with students. This becomes a part of your soul-gardener's green thumb, and you use it seamlessly and to great effect.

- To further unpack this quality, see pp. 23-26 of The Will to Learn.

- For more on this idea of “soul-gardening,” see Chapter 1 of The Will to Learn and this article.

- For more on what to do when you get overwhelmed with the Five Key Beliefs, see this article: “I Can't Handle Five Key Beliefs Right Now. Gimme Just One.”

- Quality 4: The Five Key Beliefs are dependent on context. Beliefs are largely context-dependent, especially in secondary students. This can be observed by gathering all the teachers who teach the same student and asking them how motivated that student is. You will find that, in nearly all cases, the student's motivation waxes and wanes based on the context the student is in — highly motivated in math, completely demotivated in ELA, middlingly motivated in Phys Ed except during weight training exercises, etc. How we shape the school or classroom context is enormously predictive of the degree to which students will pursue mastery with care (i.e., demonstrate motivation). And we shape that context every day, during every encounter. We only control a sliver of the total context of our classroom, but what we do control is massively influential.

- To further unpack this quality, see pp. 26-29 of The Will to Learn.

- For an article related to this, see “Not Just Home Life: A Critical Mass of Belief-Supporting Contexts.”

- Quality 5: The Five Key Beliefs are malleable. Research on student mindsets (i.e., the Five Key Beliefs) has made it clear that mindsets can and do shift even from very simple and brief interventions. This means that comments like “So-and-so is just an unmotivated student” aren't accurate or helpful because they disempower the teacher to do the kinds of things that influence student motivation. This provides us a solid segue into the 10 tools I recommend using for influencing the Five Key Beliefs — we'll turn to those now.

- To read about a study that demonstrates this important quality, see pp. 29-31 of The Will to Learn.

How Can We Cultivate the Five Key Beliefs?

In my first draft of The Will to Learn, I had 55 different strategies for influencing student motivation. I can still remember taking that file on my computer and dragging it to the trash bin, followed by me apologizing to my editor and asking for more time to write the book.

In the subsequent draft, I took the initial list of 55 strategies and reduced it to just 10. Here they are:

- Strategy 1: Track Attempted Moments of Genuine Connection (MGCs). These are brief (30- to 60-second) interactions with individual students, during which you attempt to make a student feel valued, known, and respected. You keep track of these attempts on a clipboard.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 47-63 in The Will to Learn, pp. 30-32 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 2: Improve at One Thing. This strategy is central to all of my writing. Even though I write about quite a few things, I'm only ever pushing myself to improve at one thing at a time. Many of the tools and ideas I write about are at play in any given week of school, but I'm only pushing myself to improve with one tool or idea at a time. This focuses my efforts and yields faster improvement than distributing my improvement efforts too thinly and broadly.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 64-90 in The Will to Learn.

- Strategy 3: Gentle Urgency. This is all about using class time well and signaling to our students that class time is sacred, while at the same time, we are human beings who won't always get it right and sometimes need rest.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 91-100 in The Will to Learn.

- Strategy 4: Mini-Sermons from an Apologist Winsome and Sure. These are frequent, brief (30- to 60-second) “sermons” in which we as teachers explain why the work we are doing is valuable. During these mini-sermons, we demonstrate that we respect our students' skepticism about the Value of learning while at the same time casting a confident vision for the full-spectrum Value of what we're doing.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 123-141 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 5: Feast of Knowledge (Or: Teach Stuff, Lots). The research is pretty clear: the more we know about a subject, the easier it is to learn about that subject and feel motivated in doing so. The whole idea with this strategy is that learning things ought to be presented as a feast, not a chore. Using simple methods like teaching all you know, incorporating knowledge-rich sources, and helping students memorize “sets of knowns,” this strategy brings knowledge-building to the foreground and cultivates Value as it does so.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 142-156 in The Will to Learn or Chapter 3 of These 6 Things.

- Strategy 6: Valued Within Exercises. These are a set of moves designed to guide students to create their own reasons for valuing school. They help students habituate the life-critical task of valuing something for their own reasons rather than the reasons of others. Students need guided practice in generating Value for the work of learning within themselves, just as they need adults who model this Value for them (Mini-Sermons).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 157-166 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 7: Woodenize All of It. In this strategy, we seek to effectively teach, model, and reinforce every learning-conducive behavior that we expect of our students. The strategy is named after legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden, who famously began each basketball season by teaching his players how to put on their socks and shoes. This strategy is all about making effective effort clear for all of our students.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 175-193 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 8: Define Success Wisely, Early, and Often. Most students do not have a clear or helpful idea of what success in school looks like. In this strategy, we seek to communicate our vision of success to students and help our students generate and reflect upon their own definitions of success.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 194-205 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 9: Unpack Outcomes, Good or Bad. This strategy is all about pointing our students' attention toward wisely interpreting how their learning is going. If we don't do this, students are likely to make maladaptive interpretations of both bad results (e.g., “I did bad on the test; I'm stupid”) and good results (e.g., “I did good on the test; I'm smart”).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 206-218 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 10: Normalize Struggle. The thing with struggle (e.g., nervousness in public speaking; stress about tests; difficulty writing; self-consciousness when exercising in Phys Ed) is that students often interpret it as something unique to them. They then take this interpretation and form a devastating and growth-halting conclusion: “I'm uniquely ill-suited to the work we do in this class.”

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 230-242 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

A One-Hour Talk on How the Five Key Beliefs Work in Practice

In May 2024, I gave a talk to AP teachers about student motivation troubles, how to think more productively about these struggles, and what to do about them. You can listen to that talk in this video.

Still Got Questions About the Five Key Beliefs?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: you get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Michelle Tyner says

Thank you for creating this insightful and timely resource!