The Value belief is the second of the Five Key Beliefs of student motivation, which I unpack at length in The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own and in Chapter Two of These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most.

- What is the Value belief?

- Key Ideas About the Value Belief

- Key Idea #1: The Rainbow of Why = the spectrum of Value.

- Key Idea #2: American secondary schools rely too heavily on utility and relevance; this imbalance harms the hearts of our students.

- Key Idea #3: To remedy our overreliance on relevance and utility, we’ve got to “paint” intentionally with all the other colors of the Rainbow of Why.

- Key Idea #4: It helps to represent learning in lots of ways.

- How can I cultivate the Value belief in my classroom?

- Extra “Booster” Strategies for the Value Belief

- Common Questions and Hang-Ups About the Value Belief

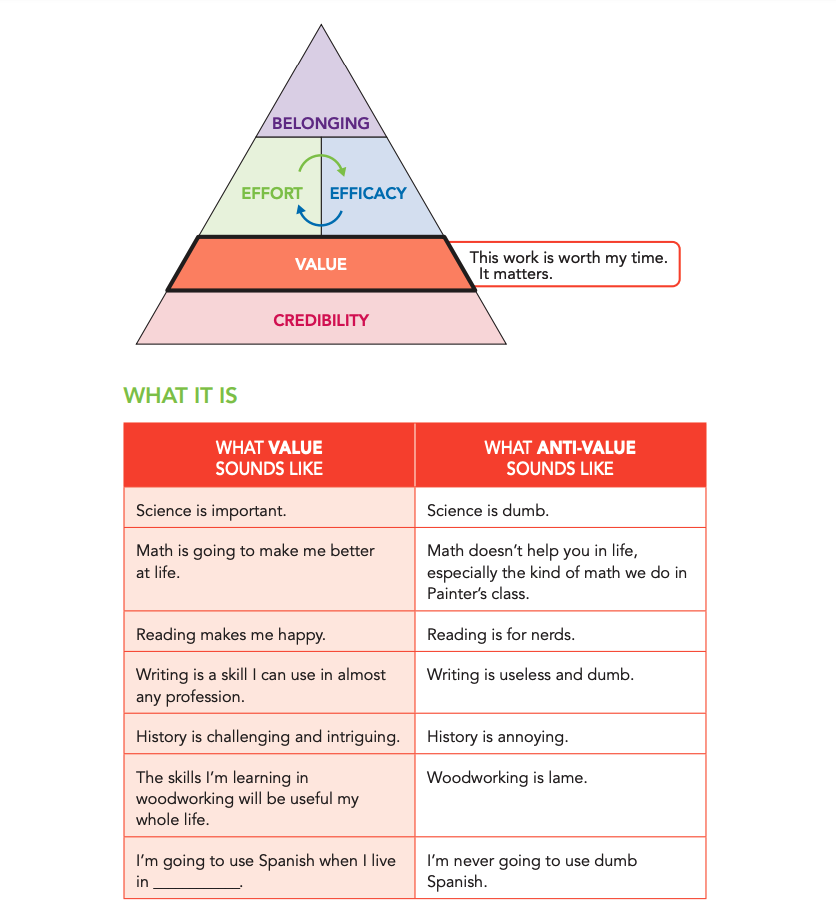

What is the Value belief?

For a human to be optimally motivated in an endeavor, they need a core question answered: does this work actually matter?

Unfortunately, the average secondary student answers this with a simple “no.”

To start to remedy this, there are a few key ideas we need to understand.

Key Ideas About the Value Belief

Key Idea #1: The Rainbow of Why = the spectrum of Value.

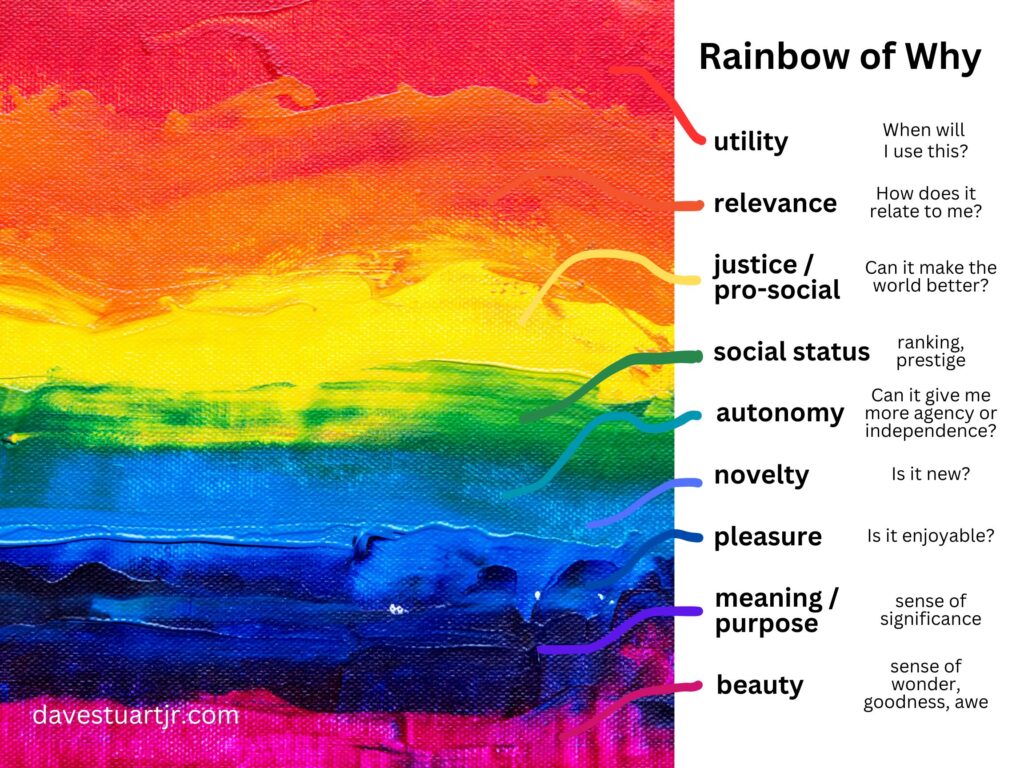

When I was doing the research on the Value belief, I was overwhelmed by all the angles researchers took when examining the topic. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that the best way of representing this range of Value angles was with the color spectrum.

I love this image for several reasons:

- In its colorfulness, it communicates beauty, playfulness, and hope. That’s exactly how I want you to think about cultivating Value. You’re not trying to strong-arm your students into valuing what you do; you’re inviting them into a world of color and wonder.

- In its painted-ness, it suggests creation, art, and innovation. Too often in education we talk about motivating students as if it’s a chore. Instead, cultivating the Five Key Beliefs is a privilege and a pleasure. No matter what you teach, the wonderful thing is that your subject is good and worthy because education is good and worthy. All of your students can benefit. And so you need not groan beneath the weight of cultivating Value; you need only to get out your paints and play.

The Rainbow of Why shows us the great deal that's possible within the Value belief. But it also helps us to see how our biases tend toward treating just two of the “colors” of the rainbow.

Key Idea #2: American secondary schools rely too heavily on utility and relevance; this imbalance harms the hearts of our students.

Let’s explain what I mean by utility and relevance in the Rainbow of Why, and then I’ll explain the shortcoming of relying too much on either in school.

Utility is usefulness. It answers the question, “When will I ever use what I’m learning right now?”

When a student believes this part of the Rainbow of Why, it sounds like:

- “I’ll use fractions when I bake cakes.”

- “I’ll use grammar and mechanics in my career as a writer.”

- “I’ll use strength training in physical education class during soccer season.”

In most secondary education cases, students don't see the Utility of their secondary education. And because we live in a culture that heavily values utility, we tend to make utility-based arguments when we hear the age-old question: “But why do we have to do this, teacher?”

I've asked thousands of teachers how they answer this question, and well above 80 percent of educators answer with something to do with utility: “You’ll use this when you ____ .”

There are at least two problems with so many of us defaulting to utility explanations.

- First, they don’t work all that well, especially when we make utility arguments about the future: “People discount the value of temporally distant rewards to an extreme and irrational degree” (Bryan et al., 2016). In other words, leaning on utility in math class — “Dave, you’ll use this geometry someday if you’re ever building a shed” — is like telling me that exercise or a diet will help me live healthier in twenty years. Living healthy longer is a temporally distant reward; it sounds great, but not nearly as great as another slice of pizza with ranch on the side — and that’s coming from a middle-aged man. Teenagers have an even harder time valuing things that are temporally distant.

- Second, when we overuse utility, I think we send a motivationally deadly unspoken message. This message is, if you can’t use what you’re learning in school then there’s no point in learning it. Which leads to wonderings like, “Wait — my teacher can't say when I’ll use this today? Ha — I got 'em! Time for me to sit back and relax.” Over a hundred years ago, edu-philosopher Charlotte Mason basically called this when she warned against using too few methods for motivating young people lest we call one set of motives “unduly into play to the injury of the child’s character.” It’s that last part — “injury of the child’s character” — that I find so haunting as I look into the eyes of a student that demands to know when today’s lesson will be used.

Now, far be it from me to bring up a problem without proposing the silver lining. Here’s how I think we overcome a culture obsessed with utility.

Teach that no adult knows just what they know from their K-12 education. I had a lovely, talented, and hard-working eighth-grade science teacher, Mrs. Lavoie. She was just fantastic. But believe it or not, when I try remembering things from her class as a middle-aged man today, I can call to mind just two things: a picture of a food web and her warm, smiling face.

So does this mean that Mrs. Lavoie taught me nothing that I use today? That the 180 or so hours I spent in her science class were wasted? Heavens no! What a silly and un-sacred thought. Yet this is just what some adults seem to think when they get up on TED stages and rail against how the industrial model of education is ruining lives today.

The reality is that during the reading of these past three paragraphs, your mind has been transformed. Your neural pathways are just a bit different. If I were to ask you to think in exactly the same way this evening as you thought this morning, it would not be possible. Why? Because due to your neuroplasticity, you are a creature ever changing.

With that said, teach your students that their educational time is precious and deserves never to be wasted. In the spirit of gentle urgency (see Strategy 3 in The Will to Learn), I want my students to know that it’s important to me that our class time is always wisely invested. I have no tolerance for things like busywork — activities meant to keep kids occupied and placid. Instead, we are obsessed with moving toward mastery in our discipline. “We are not about busywork,” I often say to my students.

And that, dear colleague, is something that will never waste your time and will always enrich your life. These are the kinds of things we must say relentlessly to repair student hearts that have been malformed by utilitarianism.

Now let's look at the other overused “color” on the Rainbow of Why: relevance.

Relevance is relatability. It’s “How does this lesson connect with my interests, values, hobbies, and goals?”

In a young person, it sounds like:

- “I’m interested in being a YouTuber, so this video editing unit in my TV production elective is useful to me.”

- “I plan to have children someday, so this family science lesson on infant-rearing is important to me.”

- “I like writing songs to play on my guitar at home, so when we analyzed those Taylor Swift lyrics in English class, I resonated with that.”

The biggest problem I see in teachers who rely too much on relevance is that they presume that student interests are more homogenous than they actually are. For example, in a blog article I once read but will not cite out of respect for the author, the topic was culturally relevant pedagogy. Now mind you, I have a deep respect for CRP, having matriculated at an undergraduate program that was shaped around Ladson-Billings’s Crossing Over to Canaan. I believe all good teaching is culturally responsive.

In the article I’m referencing, the author provided an exemplar lesson in which students were asked to analyze a Taylor Swift song rather than an Emily Dickinson poem. The Taylor Swift song, the author implied, was relevant to student cultures in a way that the Dickinson poem was not.

This is deeply problematic to me as a Five Key Beliefs practitioner for the following reasons:

- On the one hand, the student who has total interest in Taylor Swift — a Swiftie through and through — has now received a signal that only optimally relevant things are worth studying in school. In the long-term, signals like this undermine the Value belief because not every lesson of every discipline can be optimally aligned to one’s individual preferences.

- On the other hand, the students who have zero interest in Taylor Swift — anti-Swifties, let’s call them — have now received an anti-Belonging signal that their identities are at odds with the kind of work done in their English class.

- And for this latter group, the teacher’s Credibility has likely diminished because the teacher seems to care more about Swifties than about anti-Swifties.

My point is to critique the popular narrative amongst American educators that relevant curricula are a simple and self-evident good. First of all, there is no classroom in the United States where relevance is simple. Our students are too diverse, their identities too complex. And second, in an Internet-saturated culture like the one we teach in, is an individually relevant education truly the best possible good we can provide for our students? I say let the algorithms master individualization; in school, let’s focus on mastering the disciplines.

So how do we solve our overreliance on relevance? Basically, teach a broadly representative curricula that showcases the breadth and depth of your discipline. Dr. Bishop so aptly called for “mirrors and windows” in the curriculum: learning experiences that reflect your students, that are relevant to them, and learning experiences that show your students other worlds.

In other words: Just do the darn Dickinson poem! And do a song from pop culture once in a while. It’s important for your students to experience the fullness of what your discipline or art offers, and that means giving them lots of chances to experience all the breadth and depth of what you teach.

Key Idea #3: To remedy our overreliance on relevance and utility, we’ve got to “paint” intentionally with all the other colors of the Rainbow of Why.

So if we're to paint less of the utility and relevance colors of the Rainbow of Why, what are we left to paint with? Let’s now examine the other color avenues to Value.

Social status is our sense of how we measure up to others. It answers questions like, “What’s my ranking? How does this activity affect my ranking? Am I more or less prestigious amongst my peers because of this thing?”

In a young person, social status sounds like:

- “My debate speech in civics class today was so much fun — all of my friends applauded.”

- “I can’t wait until the bake-off in food and nutrition class next month — it’s going to be fun to compete with my peers.”

- “I love playing Kahoot in science class. It’s so intense to compete.”

- “If there’s not a competition involved in a classroom, I’ll probably not be interested.”

The main drawback of the social status angle is that it often depends on competition, as I'll explain later in the “questions and hang-ups” section of this article (see also pp. 118-120 of The Will to Learn).

Next, we have autonomy.

Adolescents are hypersensitive to being autonomous. They want control of their lives and the independence to make their own choices.

The autonomy angle can sound like this in a young person:

- “I’m learning personal finance so I can save up for a car.”

- “I like how in English class we get to choose our own books for independent reading.”

- “Ms. Smith’s a great agricultural science teacher because she lets us pick from several options for showing our mastery in each unit.”

- “I’m paying attention in history so that I can have an informed discussion with my dad about politics.”

Providing autonomy for students doesn’t require a major curricular overhaul. In one study, framing a request in terms of what one “should” do versus what one “might consider” prevented adolescents from internalizing a message or changing their behavior (Bryan et al., 2016). The latter’s added sense of autonomy made a difference. One tiny language shift; big shift in perceived Value.

Now let's look at the justice/prosocial angle.

Justice is righting wrongs in the world. It’s resisting what is evil or unfair. It’s standing up for the oppressed. It’s the pursuit of rightness.

Prosocial behavior is psychologese for something smaller than justice — think of it as the simple act of helping another. Though less dramatic than justice, it’s still deeply good. Raising money for someone who has lost their home is prosocial; stopping to help a peer in the hallway who has dropped their belongings is prosocial.

This can sound like:

- “I’m into this research paper that we’re writing in English class because my topic is something that I believe is important and needs to improve in the world.”

- “I enjoy earth science because I’m learning more about the environment and how it can be positively or negatively affected by my choices.”

- “I like what we’re studying in health because I’m learning to see the manipulative practices of food companies and how they encourage poor eating choices.”

- “Personal finance is teaching me how to ‘stick it to the man' by resisting consumer spending urges and saving a bit from each paycheck.”

It turns out that justice and/or prosocial angles can be especially appealing to adolescents. In another part of the study I mentioned earlier, Bryan et al. demonstrated with a 536-student study that students were more likely to eat healthy foods when taught about the manipulative and unfair practices of the food industry (e.g., engineering junk food to be addictive and marketing it to young children) versus just being taught about unhealthy and healthy eating.

Next, novelty.

Novelty is when something’s new. You’re not used to it — in a good way. Its newness makes it interesting.

It gets activated by things like:

- Referring to your discipline in a way students are not used to (e.g., in Caroline Ong’s mini-sermon example; see this article or p. 128 of The Will to Learn, in which she says, “Mathematicians are lazy!”)

- Using a new review game in Spanish class

- Starting a new unit in computer science

- Starting a new book in ELA

What folks often miss is that novelty can come from things as small as the language you use or the way your classroom makes every student feel like they are somebody. In other words, novelty need not come from constantly coming up with new lesson blocks.

Next, let's look at enjoyment/pleasure.

Enjoyment is fun. It’s what we typically associate with being happy or entertained. It’s the source of hedonic pleasure — a counterpart to the eudaimonic pleasure that we’ll see in a moment.

It sounds like:

- “It’s fun answering the problems in the math textbook because they are just the right amount of challenging for me, and I usually get them right.”

- “I always look forward to Pop-Up Debates because I know someone will say something funny and we’ll all laugh.”

- “My psychology teacher is really good at his job; he always makes learning fun.”

The master play here is helping students broaden their sense of what is enjoyable and pleasurable. Just like beauty, enjoyment and pleasure are subjective. They are changeable, expandable states that can be influenced; we’re not born with a fixed set of things we’ll find fun and things we won’t. So what you’re after is helping your students to find joy and pleasure in the challenge of learning, in things that are not normally enjoyed by folks like them.

One great teacher move, then, is to expand your own sense of what is enjoyable and fun. Every half year or so I try enjoying the pursuit of a new hobby, the learning of a new topic, the cooking of a new food, or the enjoyment of a new kind of music.

Now let's get to the really good stuff: meaning and purpose.

Meaning is significance beyond the self. It’s being caught up in something bigger than you and your life. It’s the source of what philosophers call eudaimonic pleasure. It’s what management thinker Simon Sinek is talking about in his popular TED-talk-turned-book, Start With Why.

Purpose is a sense of what you’re here for. It’s the impact you’d like to have in the world. It’s the thing you’d like to look back upon at the end of your life and say, “I accomplished that. I lived up to that.”

In a young person, this sounds like:

- “I’m going to become a nurse one day because I love to help people. Because of that, I care about what we’re learning in our anatomy class. It aligns with my purpose.”

- “When I read the end of the novel for English class last night, I couldn’t describe the emotions within me. It felt good and sad and terrible and beautiful.”

- “Art brings people joy. This is why I love to make and share my art.”

- “I want to serve my country as a Marine one day, and so I’m all in when it comes to physical education class.”

- “My mom had breast cancer when she was thirty, and so what we’re studying in health class is especially significant for me.”

Psychologists are especially interested in eudaimonic pleasures like meaning and purpose because they are associated with lots of beneficial side effects. As Telzer et al. put it, “The presence of meaning in adolescents' life is associated with a host of positive indices of well-being, including higher self-esteem, higher happiness, lower distress, lower anxiety, and greater academic motivation” (p. 6,601).

Cultivating a sense of meaning and purpose in the work of learning is one of the best gifts you can grant a young person. Meaning and purpose are nuclear fusion reactors of the Value belief; they form a foundation for a flourishing life.

Finally, we arrive at beauty.

Beauty appeals to the aesthetic senses. It is deeply subjective and deeply influenced by context. One person can sit outside in a quiet park, listening to the wind through the trees, and be deeply moved by the beauty of the moment. A person sitting next to them, meanwhile, can be completely bored.

This can sound like:

- “When my peer gave a presentation in science class today, I was moved by how well she spoke.”

- “In physical education class, we watched an interview of a paraplegic who goes to the gym each day for exercise. I kept thinking about it all day — not because I felt sorry for the person but because their attitude was beautiful.”

- “In our ethnic studies elective, we got to read interviews from Holocaust survivors; though all were sad, some of them were beautiful in the hope I read between the lines.”

Despite its subjectivity, a strong sense for beauty in school is nothing short of a superpower. When a student learns to see beauty in the everyday (e.g., in Caroline Ong’s math class, where the beauty of math is spoken of often; see pages 127-129 of The Will to Learn), that student will have little trouble valuing school.

Key Idea #4: It helps to represent learning in lots of ways.

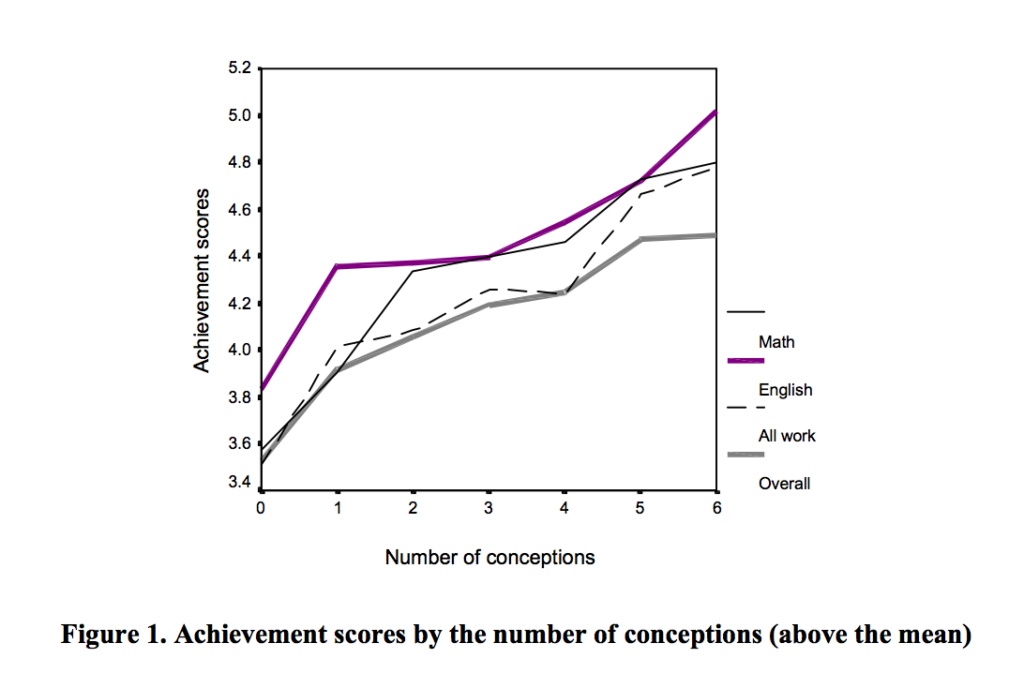

Nola Purdie and John Hattie did one of the most interesting studies I've ever come across. They wondered how students' conceptions of learning would relate to their outcomes in school. (If you want to read more about this, see this article or pp. 115-118 in The Will to Learn.) Their tool focused on six core conceptions:

- Learning as gaining information

- Learning as remembering, using, and understanding information

- Learning as duty

- Learning as personal change

- Learning as process

- Learning as social competence

Interestingly, there was no single “right conception” of learning that led to better achievement. Instead, students' achievement improved based on how many conceptions they held.

The more conceptions they had, the better they tended to do in school. I don’t know why that is, but my guess is that a student with such a broad array of outlooks has an easier time engaging with any learning task they’re presented with. In other words, they've got lots of situations in which they can Value learning.

This is fascinating because, at least in my experience, teachers tend to assume that their philosophy of learning is the right one: “Everyone knows learning is about ______________ .” Progressive teachers are certain that learning is about the process of personal or societal change, and they generally flinch when learning is considered a duty or simply about information. On the other hand, traditionalists get frustrated when learning is presented as a social-emotional process or a personal journey; they focus on building knowledge and the importance of this for a well-functioning democratic society.

But according to Purdie and Hattie, both the progressives and the traditionalists are only partially right. The most productive view of learning is one that encompasses all of their views.

It’s likely that the most robust method for broadening our students’ conceptions of learning is contextual rather than interventional; creating classrooms in which all of the conceptions are reinforced by learning tasks. Practically, this means using the conceptions as a filter through which to view our lessons and assignments. In X lesson or Y assignment, what conception of learning am I reinforcing?

The big idea for me is that I want to internalize each of these conceptions of learning — I want to memorize them and use them — so that I communicate them all throughout the year. This, I hope, will help me build more lessons and assignments that engender the full spectrum of conceptions in my kids. In light of Purdie and Hattie’s research, I can no longer afford to emphasize solely the conceptions I’m drawn to; I need to communicate them all.

Value, it turns out, is less about what learning is than it is about why learning matters.

But the Hattie/Purdie study is a useful complement to this idea of painting with all the colors of the Rainbow of Why.

How can I cultivate the Value belief in my classroom?

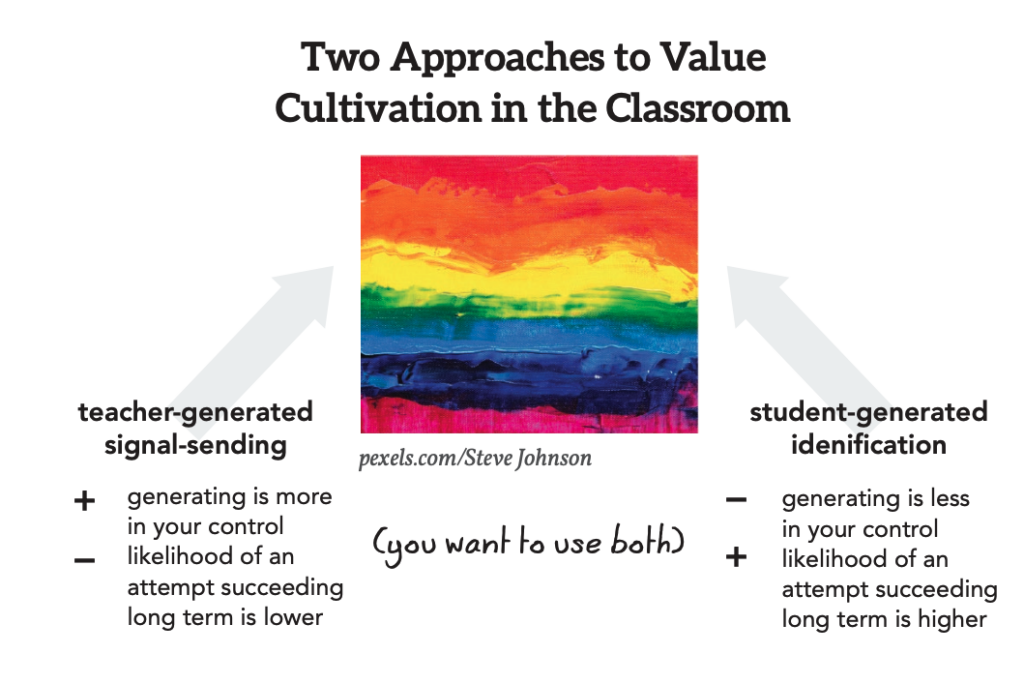

When it comes to cultivating Value, you want to focus on a two-pronged approach.

At the end of this section, you'll see a list of articles I've written over the years sharing many ways that you can cultivate the Value belief in your students. But when I wrote The Will to Learn, I was determined to identify the fewest, biggest-bang-for-your-buck strategies I could. I narrowed and narrowed and narrowed until finally I arrived at three core strategies for cultivating Value.

- Strategy 4: Mini-Sermons from an Apologist Winsome and Sure. These are frequent, brief (30- to 60-second) “sermons” in which we as teachers explain why the work we are doing is valuable. During this mini-sermon, we demonstrate that we respect our students' skepticism about the Value of learning while at the same time casting a confident vision for the full-spectrum Value of what we're doing.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 123-141 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 5: Feast of Knowledge (Or: Teach Stuff, Lots). The research is pretty clear: the more we know about a subject, the easier it is to learn about that subject and feel motivated in doing so. The whole idea with this strategy is that learning things ought to be presented as a feast, not a chore. Using simple methods like teaching all you know, incorporating knowledge-rich sources, and helping students memorize “sets of knowns,” this strategy brings knowledge-building to the foreground and cultivates Value as it does so.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 142-156 in The Will to Learn or Chapter Three of These 6 Things.

- Strategy 6: Valued Within Exercises. These are a set of moves designed to guide students to create their own reasons for valuing school. They help students habituate the life-critical task of valuing something for their own reasons rather than the reasons of others. Students need guided practice in generating Value for the work of learning within themselves, just as they need adults who model this Value for them (mini-sermons).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 157-166 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

Extra “Booster” Strategies for the Value Belief

Outside of the core strategies outlined above, here is an ever-updating list of brief articles I've written to describe more Value boosters.

- Value Indicator: “When Am I Ever Going to Use This?”

- End of Year Value Booster: the Led Tasso

- End of Year Value Booster: Ask Them

- End of Year Value Booster: “What Was It All For?” End of Year Mini-Sermon

- Underused Value Angle: Science Class is Beautiful

- How to *Have Fun* Helping Your Students Value School This Year

- A Pop-Up Debate for Helping Students Value Writing

- Value Booster: Why Are You Here?

- Credibility/Value Booster: Is that a Treasure Chest I See You Carrying?

- The Desire for Knowledge: One of the Most Underplayed Approaches to Value-Based Motivation in US Public Education Today

- What If Schools Were Places Where the Value of Learning Was Obvious?

- How to Help Students Value Learning Just Because It's Learning (Video)

- Simple Intervention: Bill Damon's Approach to Helping Students Value School

- Principles Must be Proven; Use “Value Drills” to Help

- Simple Interventions: Building Connections to Help Kids Value Coursework

- An Expectancy-Value Pop-Up Debate

- A Simple “Expectancy-Value” Activity for Helping Students Care about Your Coursework

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About the Value Belief

Is competition a valid way to help my students value learning?

Competition is tricky because some people really like it and some people really don’t. When competition comes up in my teacher workshops as a source of Value for students, I like to ask the room two questions. First, I ask students to raise their hands if they love competition, and then I ask them to raise their hands if they loathe competition. Hands always go up for both questions. And so, what are we to do as teachers who want all of our students to have productive and enjoyable learning experiences in our classrooms?

I think that part of the answer is found in the Rainbow of Why. When we think of a classroom competition — say, a game of Quizlet or Kahoot on the mild end or a March Madness–style bracket debate on the other — a few facets of the Rainbow are in play.

Social status: “If I win, I move up! But if I lose, I move down.” Some students may not enjoy competition because they don’t need social status to be a motivator in a given course; for example, they may find history fascinating on its own terms without incorporating a game, and so a competition feels like a needless risk. Whereas competition-lovers may find history boring and, therefore, the chance to rise in social status is highly appealing.

Another trouble with the social status draw is that students who could potentially be motivated by an improvement in social status during a game you’re playing may view themselves as so incapable of winning (an Effort/Efficacy issue) that they completely stop trying.

Enjoyment, pleasure: Some students are socially and emotionally mature enough to compete in games without deep concern for who wins or loses; they simply enjoy the different mode of learning.

So what are we to do? I see a few opportunities.

- Ask your students my two questions above: Who loves competition? Who hates it? Emphasize to them that part of the way in which you’ll create a room of challenge for everyone is through occasional competitive events. You know that this will be motivating for the competition-lovers and frustrating for the competition-haters, but the reverse will be true during learning blocks where you choose not to involve competition.

- The rest of the Five Key Beliefs strategies (see this page or The Will to Learn) will help make competitions safer in your classroom for students. As their ability and Efficacy improve, so too will their eagerness for games. As they come to believe they belong in your room no matter the outcome of some competition, they will be more likely to find the games you play in your class another important part of the work they get to do with you.

What do I do if my students only care about grades?

Most teachers I speak with nod their heads when I describe grade-mongering — that is, when a student is only willing to do course work that is graded. A monger is a dealer or trader; for example, a fishmonger deals or trades only in fish. And a grade-monger is someone who deals or trades only in grades. Like all of our students, those caught up in grade-mongering are good people.

Grade-mongering, however, is a massive obstacle to proper motivation in our secondary schools. As I call to attention at every talk and workshop I give, schools exist to promote the long-term flourishing of young people, specifically by teaching them to master the disciplines and arts. Where in that definition have I included grades?

Now, let me be clear: I’m not a “get rid of grades” guy. But in my own practice and research, I don’t find a fixation on grading systems to be necessary for helping my students to move their hearts away from grade-mongering and toward a mastery

orientation.

The main thing that I find helps is that I keep my grading system as simple as possible. I don’t have complete autonomy over this — for example, my department decides on the 60/40 summative/formative weighting split that we use for our marking period grades — but wherever I do have autonomy, such as in deciding what to grade as formative and how to grade things that are formative, I lean heavily toward simplicity.

Let me expand on my grading practices, as I am often asked questions about them.

- Although I require students to complete a daily written warm-up, I rarely grade this. Instead I’m walking around the classroom as my students complete the

warm-up and addressing any problems I see. - Because summative assessments hold a lot of weight in my system, I like to offer students the chance for test corrections as a means of regaining partial credit for errors at test time. I talk to my students about how test corrections are our version of a curve for a test. I remind them that the point is mastering the material and that test corrections give us another chance for doing that.

- I give students five emergency passes at the start of the semester that they can use for submitting late work; otherwise, I don’t accept late work.

- I try entering no more than two or three things into the grade book in a given week. This saves me time doing data entry and reduces my opportunity for making errors entering grades. It also reduces complexity for students trying to improve their grades.

Overall, the most powerful thing we can do to help students who are obsessed with grades is speak to the truth that our goal is mastery, not grades. I advise teachers to be as creative and passionate and consistent as they can be with little messages like this, which are typically spoken for the whole class to hear when the matter of grades comes up. At the same time, though, it’s important to express compassion for students who are anxious about grades. This is a hard way to go through secondary school.

May our classrooms be rich in little nudges away from grade-mongering.

What if my students come from homes where education isn't valued?

This one is easier to respond to. First, I’ve been teaching and parenting long enough to know that when educators make assumptions about a student’s home life, there’s a lot of ego blindness going on. I always tell colleagues, “The only home I can speak authoritatively on is the one I live in. And even then, there’s a lot I don’t know!”

Second, my students’ homes are not contexts that I control, and, therefore, I do not spend time or energy fixated on what may or may not be valued in them. It is just not something I have found profitable to attend to. But what I absolutely must attend to, with great vigor and earnestness, is the degree to which education is valued in my classroom. The person most responsible for the values of that place is me.

To make good on that responsibility, I recommend Mini-Sermons and Valued Within Exercises.

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: you get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply