If there is one way that you can begin implementing the writing and speaking/listening portions of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in a simplified, manageable, high bang-for-your-buck fashion, it's simply this: have students argue.

If there is one way that you can begin implementing the writing and speaking/listening portions of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in a simplified, manageable, high bang-for-your-buck fashion, it's simply this: have students argue.

Frequently.

Whether you teach science, social studies, technical subjects, ELA, even math, argument is a dependable path to enlivening your classroom, promoting long-term student flourishing, and pwning the heck out of a large chunk of Common Core literacy standards.

But don't just take my word for it. In an article back in 2011, gurus Jerry Graff and Mike Schmoker (their books Clueless in Academe, They Say / I Say, and Focus have hugely shaped me) warned that, though the CCSS held promise, especially compared to the preceding generation of state-created wish lists, there was still too much fluff. Their fear was that the high impact standard of argument might get watered down amongst the rest.

Separate and way not equal

Even though the research appendix discusses the “special place” of argument in the CCSS (p. 24), the only hint of such importance outside of the appendices is that the “argument standard” (W.CCR.1) comes first.

This is problematic; many will not read the appendices and, as a result, will likely spread their curriculum too thin by trying to equally teach all 10 of the basic writing anchor standards. The simple problem with trying to equally teach all 10 is that, frankly, it can't be done well, at least not by an average teacher like me.

And honestly, it's not just a teacher thing. Students enjoy becoming excellent at the biggies and spending less time on minutiae.

Choosing to focus

So if you're an average teacher like me, I advise the following non-freaked out, focused approach to the CCSS writing and speaking/listening standards:

So if you're an average teacher like me, I advise the following non-freaked out, focused approach to the CCSS writing and speaking/listening standards:

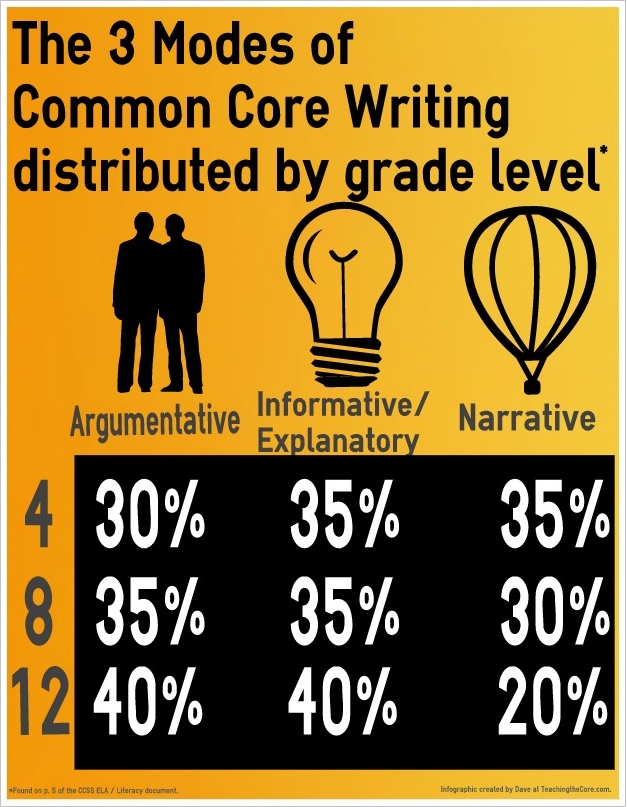

- Go big on argument, both written and spoken (W.CCR.1 & SL.CCR.1). In the infographic at right, you can see the percentage of writing types that the CCSS and NAEP recommend per grade level, and I would say those are good percentages. However, I would also suggest that our schools in general are vastly under-using the power of argument to “enliven learning” (Schmoker and Graff). Honestly, I have yet to ask students to argue too much. (In this video, I share my thinking on that.)

- Emphasize and exploit the strong link between spoken and written argumentation. I think this is one of the keys for making argumentative writing accessible. When students can enjoy, participate, and dominate in classroom debates, they begin to see and understand the beauty of crafting great arguments in writing.

- Have students speak frequently. I'm not talking about just the talkative ones, either. More about this in Part 5 of this series.

- Have students write frequently (W.CCR.1). I'll discuss this more in Part 6 of this series.

(If you're looking for what I do with the Common Core anchor standards in reading, check out Part 2 on Complex Texts and Part 3 on Close Reading.)

So how do we get students arguing productively?

If you're just trying to get started with argument, I recommend this first-day activity. Even if you're in the middle (or end!) of a school year, it can still work. Honestly, I would attempt this activity with every grade level I've ever taught (6-12), and I'm guessing some form of it could be effective in lower grades, too. I think it's that accessible, simple, and powerful; within five minutes of the start of a course, my students are seeing the community-building, game-like fun of argument. Eventually, there are these basic enduring understandings I want students to live and breathe as arguers:

- A claim is simply a debatable point (e.g., Tacos are the best food in the world).

- When I was in high school and college, this was the thesis statement.

- Effective arguers use evidence and logic to back up their claims, and they clearly explain how the evidence or logic supports or connects to their point.

- Herein lie the written skills of blending quotes, using transitions, and anticipating the audience's comprehension needs.

- The best arguers can argue both sides of an issue and can anticipate and pwn counterclaims.

From the first day to the last, we simply do lots of arguing. I've found no activity besides reading and writing that match it for the power to enhance my students' self-concepts, academic abilities, and character strengths. Seriously.

What does a debate lesson look like?

Here's a video I made at the beginning of the year that outlines my approach to debate; it's kind of long (8 minutes).

More recently, my students argued around this question: Does power always corrupt? This was our driving question in reading Orwell's Animal Farm, and students were encouraged to use anything or anyone we've studied in world history or literature as evidence. Below, I'll walk you through the lesson for the day of the debate; for what it's worth, this was one of the best debates I've yet seen. Remember, the reason debates work well in my class is because I invest a good amount of time into them throughout the year — it's not because I'm some magical debate coach.

Introducing the debate (5 min): Here, I remind students that staying on topic is croosch in a debate (we've recently started calling this topicality, which I learned about in Joe Miller's magnetic Cross-X: The Amazing True Story of How the Most Unlikely Team from the Most Unlikely of Places Overcame Staggering Obstacles at Home and at School to Challenge the Debate Community on Race, Power, and Education). This leads us to defining power (we go with a broad definition that includes popularity, influence, money, etc.) and corrupt (verb: to cause one to use dishonest or immoral means for personal gain).

Introducing the debate (5 min): Here, I remind students that staying on topic is croosch in a debate (we've recently started calling this topicality, which I learned about in Joe Miller's magnetic Cross-X: The Amazing True Story of How the Most Unlikely Team from the Most Unlikely of Places Overcame Staggering Obstacles at Home and at School to Challenge the Debate Community on Race, Power, and Education). This leads us to defining power (we go with a broad definition that includes popularity, influence, money, etc.) and corrupt (verb: to cause one to use dishonest or immoral means for personal gain).- Independent brainstorming (2.5 minutes): I want students to rack their own brains first. There are three main areas I want them to explore: every book we've read in Comp/Lit, every period we've studied in world history, and their own prior knowledge.

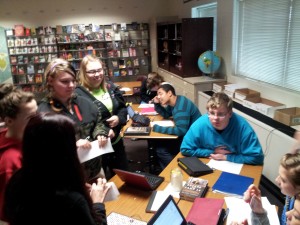

- Collaborative brainstorming (5 minutes): Even though students know that they may end up debating against people in their table groups, they share ideas with their table. More ideas tend to come during this time. Every student needs to take notes.

- Research (10 minutes): Now they can consult any resource in the room to fill out their t-charts. They only need citations if they are using a quotation or referring to something outside the scope of our classes (e.g., one student used Fidel Castro, and since we haven't studied him, she cited her source).

- Team assignments (2 minutes): I now randomly place students into one of two teams, affirmative or negative. We then flip a coin: winner gets to close, loser gets to open. Finally, I explain to students that 2-3 people can go up front at a time, and each duo/trio will have 2 minutes to speak.

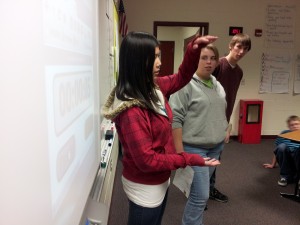

- Team strategy (5 minutes): The newly formed teams have 5 minutes to determine who will speak when and with whom. I remind students that working effectively in a new group is a social intelligence workout. Here's a video of this taking place (it's also proof that I teach normal teenagers).

- Debate (varies): During the debate, I require at least one person to come up each time that hasn't come yet (this keeps us moving through the roster but allows for repeaters to come up and recover arguments. During this debate, I experimented with tracking arguments — which team made which points, which points were stolen

- Post-debate reflection (5 minutes): I ask students to explain what they noticed we did well as a class and what we still need to work on before our end of the year debate with the sophomores.

- Teacher feedback (5 minutes): I then give students what I noticed. I use specific examples and student names, and I both praise and critique. This is a time for us to get better, not a time to give fake praise or avoid the truth.

Other debate formats I use

As you can tell, that debate format took quite a bit of time. But debates in my classroom need not be long: they can be as quick as 10 minutes or as long as a lesson. I've played with many formats over the last year and a half, ranging from a strict Lincoln-Douglas to a ridiculously hard Lightning Debate in which students have 10 seconds to speak.

However, outside of the two-sided team debate like the one described in the preceding section, I'd say that by far the most effective is the pop-up debate format (professional sounding title, right?).

In pop-up debates, students can remain in their seats at their table groups. They don't need to collaborate with their team — in fact, they don't need to be assigned a team. When they are ready to talk, they simply stand up (“pop up”) and begin their speech. I've found this to be an especially effective format when I grade them on two croosch moves: 1) their ability to paraphrase the speaker they are responding to, and 2) their ability to make their own point with support from evidence and/or logic. After doing this form of debate last Friday, I caught my students paraphrasing in a much less structured classroom discussion this week.

Ways to customize

There are multiple ways that I will customize a debate, depending on what I want students to do. Here are some variables I play with:

- Number of teams

- Time per speech segment

- Number of people per speech segment

- Number of speech segments in the overall debate (affects team strategy)

- Number of times that a person may speak before everyone else in the class has spoken

- Where speakers stand (usually either at their desks or in front of the class)

- What “moves” are speakers required to make?

- What moves will I be grading?

Ways to win

We don't usually have a winner in our debates. I'm still too new to know how to judge the teams objectively, and, so far, the students don't seem to need a winner. However, we do love when a debater delivers a good pwning to her opponent, and with that in mind, here's a list we've developed of ways to lovingly annihilate an opponent in debate:

- Point out unsupported evidence (lacking citations)

- Point out anecdotal evidence (“My uncle has all his guns in a locked safe and makes his kids take Hunter's Safety, so there's no need to tighten gun laws”)

- Point out topicality violations (when a debater strays from the topic of the debate)

So much room to grow

These are such nascent thoughts, but they are good for what they're worth!

As I mentioned before, lately I've been reading Cross-X, which is a brilliantly written true story about a debate team from Kansas City, and one thing the book has been showing me is that what we call debate in my class is pretty rudimentary.

And yet, even though I'm a total noob at debating, I still keep on. And if the Common Core vanished tomorrow, I wouldn't stop with debates. Here's why:

- because the kids get amazed by how freaking smart they can sound,

- because it's amazing to watch the kids go nuts after someone gets pwned — they act as if they just saw a bodyslam in WWE when in fact they are simply watching a purely intellectual sport,

- because there are these magical moments when shy kids turn into public speakers and when vociferous kids realize they've got a long ways to go,

- because it changes the way my students view the world and forces them to see all sides of an issue if they want to win,

- because it radically transforms the task of reading and writing arguments.

Basically, debate is one of the best things I've stumbled upon in my years as a teacher. I'd love to hear how it's impacting your classroom in the comments below.

Mary Lou Baker says

This is so helpful! Thanks!

Ted says

Great post!

A few thoughts on the debate: I like the use of Animal Farm as a source to design your debate prompt, however, the use of the word “always” seems to steer the debate in a certain direction (i.e. those on the “pro” side might have trouble defending their position in light of the fact that they can’t possibly defend ALL situations where power might corrupt). In addition, I wonder if there is enough time devoted to research (you account for 10 minutes here). The power of debates isn’t necessarily the process of plotting team strategy or “winning,” but in writing claims, considering counterclaims and, most importantly, the supporting evidence to reinforce both. It’s the “behind-the scenes” prep that makes a debate a worthwhile assessment. In fact, I always try to include a writing piece with any debate I design to highlight the importance of research. CCSS’ emphasis on short research projects lends itself well to debates, but only if the evidence collection process is carefully planned and executed by teachers. Lastly, the prompt seems not to directly refer back to the text you’ve spent so much of your instructional time teaching (you say in the LP that students can “consult any resource in the room”). The debate could be a wonderful example of a culminating assessment, but the prompt itself has to direct students back to specific examples, ideas, characters, etc. from the text.

Just my thoughts. Thanks again for the good post!

davestuartjr says

Hi Ted,

Do you have a blog or any other way that you share resources online? I ask because immediately upon reading your comment I sensed that you are the Jedi master I have been longing for to take me to the next level in maximizing the effectiveness of in-class debates. Even if you don’t have an online “home,” this comment alone will shape my thoughts and prayers and preparations for the 2013-2014 school year. So thank you for sharing in such a helpful and honest way, Ted. This kind of feedback is exactly what I need because:

1. I know my students can go much deeper into evidence-based argumentation than they did this year, but I wasn’t sure how to get there;

2. I know we can much more effectively leverage the time spent on reading complex texts into creating excellent, technical debates;

3. I’ve found skills learned in debate to be highly transferrable, but I believe there’s a great chunk of potential that I still haven’t tapped into.

So thank you, Ted — I sincerely appreciate your thoughts.

Ted says

Hi Dave,

Thanks for your very kind (and funny) response. No blog, I’m ashamed to say. I do PD for various central Indiana schools on CCSS, and I’ve enjoyed following your blog! Keep up the good work, and I hope we can continue the dialogue from time to time.

All the best,

Ted

Milissa says

Dave, I came across your site today while looking for DBQs. I have been all over your site, reading many of the blogs- and others comments as well. I really appreciate the blogs and videos on debating. I tend to open new tabs instead of pressing the back button and I’ve lost my way. I am really interested in the debate sheet that you created. I cannot remember if I saw a picture of it somewhere or if it was in a video. I’ve been at this for hours! Can you please tell me where I saw this or can you please send me a link. We debate quite a bit, but some of the students do see this planning time as free time, and I’m not sure how to solve this problem. However, I will definitely start making students summarize their opponents arguments before responding.

Dave Stuart Jr. (@davestuartjr) says

Hi Milissa,

I’m not sure which debate sheet you’re talking about — can you describe it a bit more?