In a 2020 study published in Early Childhood Research Quarterly, researchers from Temple University share an interesting finding: in a group of preschool and kindergarten classes, the complexity of teachers' language during morning message and small groups had a significant relationship to students' vocabulary development. “Together,” the researchers write, “the results imply that complex syntax is an important source of linguistic information for word learners, and that teachers’ syntax may be another, often overlooked but potentially malleable dimension of classroom quality.”

Okay, so what? What do we take away?

First of all, one study is just one study. If subsequent studies replicate the findings of this one, then we'll have a stronger sense of whether teacher syntax is something we all ought to start working on.

But given that this study appears in a peer-reviewed, scientific journal, we've got plenty of reason to take this seriously. Unfortunately, our profession's commercial vendors have flooded our ears with claims of “research-based,” and so as a group we tend to be a cynical bunch. “Okay, sure — ‘research says,'” we mutter, opening a fresh page in our notebooks so that we can doodle during the latest fad-driven professional development. We need to avoid this kind of burnt-out hyper-skepticism, instead using our minds and our mouths to ask questions like, “What research? What studies?”

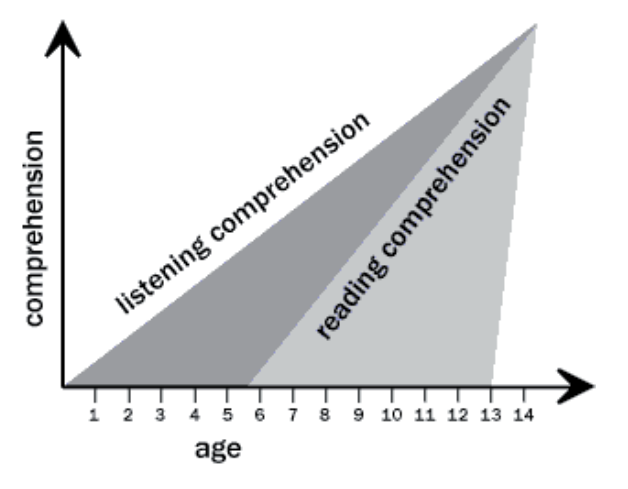

So, with a proper blend of skepticism and truth-seeking installed in our minds, we can then return to our friends from Temple University. Their findings support a well-established idea in the science of how children learn to read. Back in 1984, researchers Sticht and James conducted a meta-analysis for the Handbook of Reading Research that concluded listening comprehension outpaces reading comprehension until the middle school years. (Figure below.)

In other words, our K-8 students are going to tend to have maximum comprehension of complex language through listening rather than through reading. This doesn't mean everything becomes a read-aloud now — but it does mean that knowledge-rich curricula in the elementary grades ought to heavily emphasize listening and learning lessons (e.g., read-alouds), slowly incorporating an increasing amount of the reading of complex texts as children progress through school.

This is a critical insight when linked with what I've found to be the fundamental model for understanding how people learn to read: the Simple View of Reading. The Simple View of Reading — gosh, that is a beautiful title for something — was put forth in an innocuous little paper for Remedial and Special Education in 1986. In it, researchers Gough and Tunmer describe reading comprehension as a simple formula:

Reading Comprehension = Word Recognition X Language Comprehension

In prose: one's ability to comprehend a text depends on word recognition (decoding, phonological awareness, site recognition) and language comprehension (background knowledge, vocabulary, morphology, verbal reasoning). Importantly, there is a multiplicative relationship between the two factors — and when you multiply by zero, you get zero. When a reader has weak word recognition skills, then so much of the mind's resources will be spent on simply trying to discern the words on the page that even the richest background knowledge will not help with reading comprehension. (This is why a systematic, science-based, coherent approach to teaching word recognition in the early grades is critical. See Emily Hanford's reporting for American Public Media for introductory treatments of this topic; this article by Hanford for the New York Times is an even quicker primer.) Yet if a child has perfect word recognition skills and can read aloud a complex text in my class with perfect fluency and prosody, but that child has weak background knowledge on the text's topic and a poor grip on academic and domain-specific vocabulary, then guess what? The child will struggle to comprehend. (This is why a specific, cumulative, well-rounded, and preparatory knowledge-rich curricula is so critical in K-8. For excellent primers on this, see the Knowledge Matters Campaign website; if you'd prefer a book, do Wexler's The Knowledge Gap; if you'd prefer an article, try this policy brief from Robert Pondiscio and Lisa Hansel.)

Whew! Now that's what you call a paragraph. Can you tell I've been buried in this stuff for months!? It's been driving me insane, actually, because so much of this is beyond my control. As a classroom teacher, I can't revamp the K-8 curricula in our schools. More importantly, I can't snap my fingers and help my colleagues around the country to see the need to change how we think about curriculum, to change how we think about teacher autonomy (i.e., it can't be “I/My small team get(s) to decide everything that I/we teach” because we won't produce a coherent, cumulative K-8 curriculum that way).

And that sense of frustration about the research-to-practice gap in so many of our school systems brings me back to the article that we started with — the one that indicates a strong relationship between teacher language complexity and student vocabulary development.

Here's something we can control! The complexity of our language as classroom teachers.

We can choose to use the full extent of our vocabulary when we work with students: one-on-one, small group, whole class. We can choose to learn new words and incorporate them into how we talk. We still shoot for clarity and concision when we instruct — when you confuse you lose!* — but we aim at elevating our language. Rather than a string of simple sentences, throw in a compound now and then; get independent and dependent clauses going; rock some semi-colons.

It costs us nothing extra. We're already giving instruction, working with small groups, conferring with students and so on. Let's take this study in Early Childhood Research Quarterly as an indicator that we might as well model our best speaking and language use as we do so.

*That's an Eric Barker line from Barking Up the Wrong Tree. Excellent book, highly recommended.

Cheri Himmer says

I’m becoming addicted to your posts. Thanks for investing the brain power and shedding some sensible light to teaching.

Jenny Johansen says

Cheri – you expressed that wonderfully and precisely! I agree .

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Best to both of you, and much love to you and yours.

Christy Moore says

Emily Hanford is not an educator nor expert in reading instruction. Her articles are that from a journalist’s perspective and are not supported by reading experts and researchers in the Reading Hall of Fame. I am disappointed that you are lifting up her opinion based commentary as research.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Hey my friend! Long time no talk. I still can picture our breakfast there in Illinois.

I’m sorry to have disappointed you. My aim wasn’t to point to Hanford as an expert in reading instruction, but rather as a person who has written some popular-level primers on how reading acquisition works. Since writing this article, I’ve become apprised of diverse takes on her work, and I do agree that her work is at times uncharitable and alarmist. BUT — I still think it’s helpful to read her and be aware of the conversation.

I’ve no interest in reading wars — only in the advancement of the long-term flourishing of young people.

Not much has changed 🙂

Best,

DSJR