Update from Dave: My new book is out, and it highlights ten practical methods for improving student motivation in all kinds of classrooms. One of those strategies involves clearly and repeatedly teaching students to get better at challenging skills like note-takin for learning.

You can learn more about the book here.

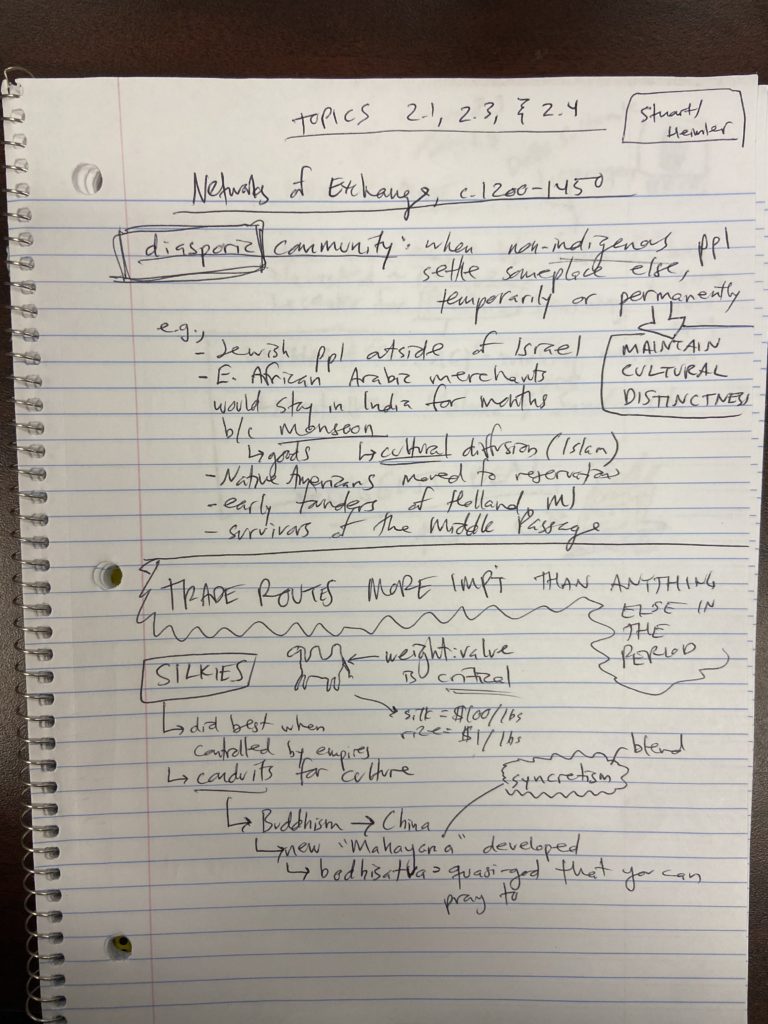

At the time of writing this, I'm five weeks into school, and my students are showing that they understand note-taking much better than they did at the start of the year. During a recent post-assessment reflection, I asked students to respond in writing to the following: What's one piece of evidence that you can find from your life during Unit 2 that demonstrates that you are making progress in your growth as a learner?

Here's some of what they shared:

Here's what my eye sees as excellent when I look at the above reflections:

- They prize efficiency.

- They are actively thinking about what they're learning while taking notes.

(E.g., “I am better at deciphering whether the information is worthy of being written down.”) - They are prizing MORE LEARNING, LESS STRESS. (E.g., “I haven't been stressing as much about homework and schoolwork so I've been able to stop procrastinating and get my work done.”)

These are all things that I want for my students because they are all things that will maximize their mastery of my course material. Now, let's look at what brought us here.

Here's what I did to help students arrive here

Start by doing

At the start of the year, I just had them take notes one night — no instruction. I gave them five or so pages of reading and said, “Take notes on these. Aim to be done in 30-45 minutes.”

The next morning, I woke up to more than a handful of emails from students saying that they had been in tears doing the notes. It was super overwhelming, it took them 2+ hours, etc.

Now, we had a baseline.

Set a goal

That next day I asked students how the notes had gone, and they mostly said, “Not great. It was overwhelming. It was stressful. I cried.”

I responded: “All right. I don't want that to happen to any of you again. From now on, I need you to try to learn everything you can from me about taking notes for learning. You each have different lives and different constraints, and you'll be working with those — not against them — to find a note-taking method that works for you.”

“Right now,” I continued, “tell your partner about how much time you have on a normal weeknight to give to this class.”

They quickly shared.

“All right,” I said. “Unless you are obsessively in love with this class material, I want all of you to have a 45-minute MAX time allotment for this class each night. Our job in the next few weeks will be figuring out how to get there.”

Let the modeling begin

From this point out, I'm not going to go more than one day of class without modeling for my students note-taking to learn. This means that five weeks into the school year, my students and I have taken notes together about twenty times. This is part of why so many of them are so clear on how to take notes successfully.

Modeling is one of the great secrets of teaching. It makes the abstract concrete.

It is also remarkably easy from the teacher's point of view. I just find a video on YouTube or a brief text excerpt, and I fire up my doc camera, and together my students and I take notes. As I'm doing that, I talk through everything I'm doing and thinking as I take notes.

Basic conventions

Whenever I take notes, I've got the title of the page up at the top, and then the source of the notes in a box in the upper right corner.

I explain to students that I'm not doing this because I'm “supposed to.” I'm doing this as a favor to future me.

Who's the reader?

I ask my students often in those first weeks: “Who is the reader of your notes? Who are you writing these for?”

By default, most of them unconsciously assume that when a teacher assigns note-taking, that means that they are taking notes for the teacher. But asking them this question helps them to unearth the obvious answer: “I'm taking these for me.”

“Right. So in terms of legibility, it needs to be readable to us. This isn't a license for sloppiness — but it should help us relax a bit. In terms of abbreviations and symbols, the reader is us — this lets us be creative a bit. In terms of drawings, sketches, and diagrams — again, it's us. We don't need to be artistic. We just need to learn.”

What is the point of note-taking?

We take notes for one reason: to learn. We learn while we take notes, we learn as we ask questions during the note-taking process, and we learn later on when we quiz ourselves with our notes.

We takes notes so we can reread them quiz ourselves with them

Rereading is the bane of a student's existence. It is the epitome of wasting time. Rereading produces a dreaded relationship with content: familiarity. Familiarity is that cursed feeling you get during a test where you say, “Oh shoot — I know this!!! Why can't I think of it right now? I'm blanking out!” Familiarity is not the same thing as knowing.

To make sure that we know something, the only thing to do is to quiz ourselves. We can do this by:

- Covering up portions of our past notes and trying to say, verbally, what we've covered up.

- E.g., “What are three examples of syncretism from 1200-1450? How did these examples happen?”

- Doing a quick skim of a past page of notes, then closing our notebook and pretending that we are giving a mini-lecture to our classmates on the page. This means lots of explaining and illustration; this means making clear key terms and ideas. After the mini-lecture, take a look at the page again and highlight anything you forgot to mention. Tomorrow, try the same thing again.

Ask your teacher

I'm never trying to hide the ball from my students. If they ask me, “Hey, Mr. Stuart, is ________ important from last night's reading?” I'll:

- Tell them “good on ya” for asking that question, and

- Share my thought process on why it is or isn't important. (I've got to keep these explanations brief in order to keep my students' attention — quick questions want quick answers.)

Drafts of learning

One important moment is when my students understand that the reading they're doing at night isn't going to be used for some kind of “gotcha” the next day. Instead, the next day we'll write about what we read, discuss it, watch another teacher's take on it via YouTube (and take notes on that take), or have a pop-up debate.

I tell them often: what I assign for home isn't the last time we'll look at it. It's the first. I expect you to do what you can to begin learning the new material. And then I'll be a good partner in helping you to take it deeper.

The 30-minute challenge

A week or so into teaching and modeling note-taking, I still have students who are taking 60+ minutes at home. By this point, they're asking me if they should drop my class. But they are the exact opposite of people who should drop my class — they're hard-working but prone to stress. I've got something that will help.

So when introducing the coming night's homework, I tell them all, “Look. Tonight we have one rule when taking notes. None of you are allowed to take more than thirty minutes. I need you to set a timer on your phone, and if you don't trust yourself to obey the timer, I need you to have a parent or guardian keep time for you. And while you're taking notes, just keep an eye on that timer. Your goal is to get through all the reading before the timer ends. Which means…

- You'll need to be strategic and picky about what you right down;

- You'll need to make the text writer your partner — use their headings and organizational structures — not your adversary;

- You'll need to smile because this is a fun challenge 😀;

- And you'll need to give yourself some grace.

“The worst thing that can happen tonight is you don't get all the way done with the reading when the timer goes off.

“That's fine.

“Shut the book, shut your spiral notebook, and go do something else.

“We'll unpack it all tomorrow.”

The next day, we process how it went — during the warm-up, they write reflectively about it, then they talk with a partner, then volunteers share out (keeping it old school wit some Think-Pair-Share). It's a really fun conversation — light bulbs are starting to flicker on. “Oooooohhhhh… I don't have to perfectly comprehend everything I'm taking notes on! Learning is a process! And I can take a hard class and still have a life!”

Taking it deeper — Stephen's reduce-it-down technique

After first publishing this blog post, I heard from our colleague Stephen re: what he does with his students. Let's call it the “reduce-it-down” technique. Here's Stephen:

I remember employing a similar note taking approach back in my college years (way back in the previous century!). Lots of shorthand, arrows, pictures, etc. My goal toward the end of the term was to take the lecture & reading notes that I had taken during the semester — maybe up to 100 pages — and condense them down to 10 pages or less. Then, on the eve of the final exam, I would condense again — down to two or three pages max. The condensing/re-writing really helped me to focus on what was most important from the course. And the 2 – 3 page final version was a great review tool on the day of the exam.

That's about it

If I'm going to teach my students to do something, I need to understand how that something works. At this point in my career, I get why note-taking matters in a class like AP World History, and I see that there are many things note-taking can teach us about life.

I really do believe that teaching students toward academic mastery is the perfect context within which to teach them about life.

Megan Buhler says

What amazing skills you are teaching to help them the rest of their lives! What amazing preparation for college where so much hinges on being able to do the reading and come prepared and do it without spending hours and hours.