In order for my students to progress to successful pop-up debates, and to drastically increase the quantity of speaking they'll do during their time in my room, I need to start with the simplest possible training ground for verbal communication: two people having a conversation. Toward that end, the first week of school finds me teaching Frank Lyman's classic Think-Pair-Share routine, and the rest of the weeks of school have me using it for roughly 80 percent of the student speaking that will happen in my room all year. [1]

Why Think-Pair-Share?

I'll start the argument for this simple, powerful strategy not with my own words, but with those of two greats of our profession, Harvey “Smokey” Daniels and Nancy Steineke. These two, far superior to me in wisdom and experience, put it frankly in their highly practical Teaching the Social Skills of Academic Interaction: Step-by-Step Lessons for Respect, Responsibility, and Results:

[Think-Pair-Share is] the most instantaneously transformational structure we can add to our classrooms. Suddenly, it's not just us doing all the thinking, talking, and working; now the kids are taking responsibility and driving the learning, too.

Intense, right? I agree with them. Here's why.

‘How to Choose Teaching Strategies' 101

I prize two factors above all others when it comes to choosing a teaching strategy for a given objective: effectiveness and efficiency. [2]

First, a strategy must effectively do what it is we want it to do. During my school year, I want to provide my kids with two things: first, the opportunity to learn the content set out by my peers and me in our professional learning communities; second, an abundance of opportunities to improve their thinking, reading, writing, speaking, and living abilities (in other words, the five elements of the non-freaked out framework).

In light of that, an effective speaking and listening strategy in my room:

- helps kids learn content;

- gives students a chance to deliberately practice one or more of the five skills I want my class to promote.

Think-Pair-Share, then, meets these requirements.

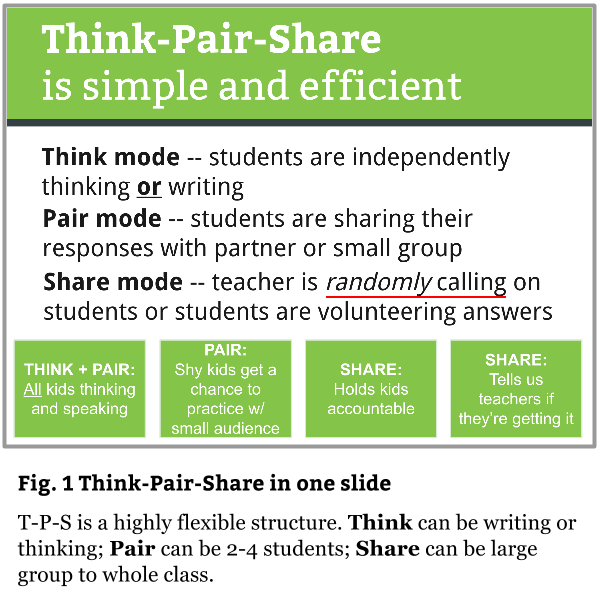

- Step One: Teacher or student provides a content-related question(s).

- Step Two: Whole class thinks or writes in response to the question(s) (this is Think mode).

- Step Three: Students discuss the question in partners (this is Pair mode).

- Step Four: Students share out answers as a whole class, both through volunteering and random selection (this is Share mode).

- Step Five (optional): Teacher provides students with speaking skills or social intelligence mini-lesson and/or the opportunity for partners to give feedback to one another on their conversation. (This step aims to aid skill acquisition; Steps 1-4 will initially increase student skill, but this skill growth will taper off without further instruction and feedback.)

Because of its simplicity, I'm almost embarrassed when I discuss Think-Pair-Share in my workshops for teachers (see Fig. 1).

Effectiveness is only the first factor for finding the best teaching strategies; efficiency is the next, and it is Think-Pair-Share's efficiency that make me persist in sharing it in workshops and using it in my classroom.

Remember: efficient doesn't mean “rushed”; it means “it gets the job done with as little waste as possible.” And I am a realist when it comes to classroom instructional time: each of the 60 minutes per day that I have with my students is precious; I cannot “let myself off the hook” if I squander a minute of class time per day because, by the end of a 180-day school year, that amounts to 180 minutes or three full class periods. That's a justice issue in my book. Too many of my students cannot afford to lose three days of English 9 or world history.

Before we dive into some specific objectives and tips for teaching Think-Pair-Share at the start of the school year, pause and reflect: are you using strategies that pass both the effectiveness and efficiency tests? What tweaks do you suspect might be possible to increase either or both of those things with strategies you currently use?

Specific objectives in my initial Think-Pair-Share mini-lessons:

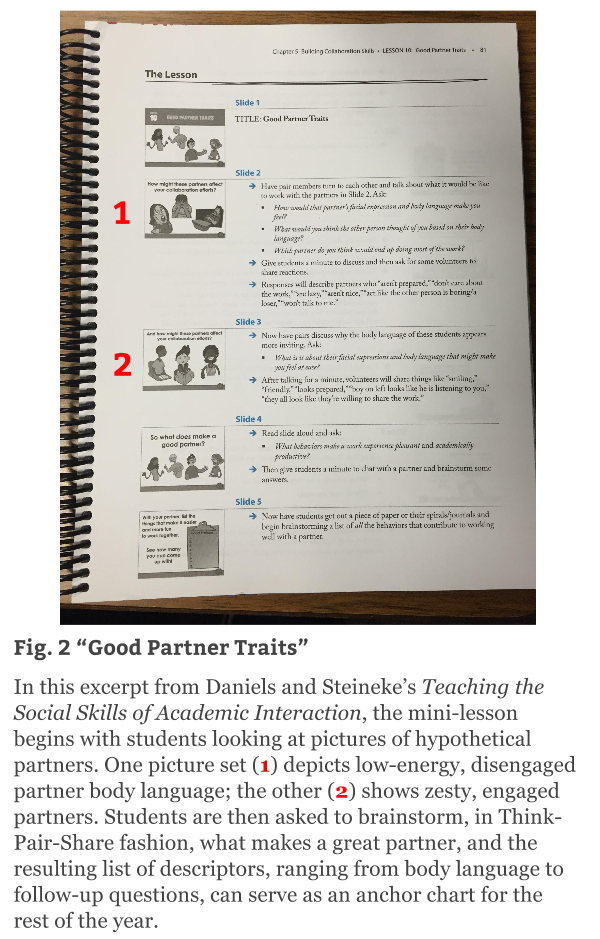

Think-Pair-Share is one of those things that I want students working on from as early as possible until the very last day of the school year, and for that to happen there are some foundational objectives I must guide my students toward at the start of the school year. While many of these are ideas I've been using for years, I owe a debt of gratitude to Steineke and Daniels for their clarifying, highly practical work in the aforementioned Teaching the Social Skills of Academic Interaction. If you're aiming to build Social-Academic Skills (or the character strengths of social intelligence and interpersonal self-control) this year, Daniels and Steineke's book is immensely practical.

Here, then, are the initial Think-Pair-Share mini-lessons I aim for, derived from both my own practice and that book:

- How will we know when Pair conversations are over? Establishing the Call to Attention signal (in my class, it's a salute — and no, the students don't need to salute back!) [3]

- How do we keep a conversation going? Asking follow-up questions.

- How do I overcome a fear of public speaking? Share mode, the random calling upon of students, and the dawning realization that speaking for the whole class to hear doesn't kill us, even if we're shy.

- How do I become a great partner, and thereby a more socially intelligent person? Understanding great partner qualities.

- What behaviors make a person's speech easier to listen to? An intro to PVLEGS.

These are things I tackle as the first week or two progresses, biting off a bit with each time we conduct a Think-Pair-Share. Remember: I aim to get into my curriculum quickly (see “#3: ‘Start Slow, Finish Fast' is true for some things, but not for everything” in this article.)

Final tips for teaching Think-Pair-Share

Here's a bit of a closing smorgasbord of tips for you; and please use the comments section of this article to ask further questions or share more tips.

1. Ensure every student is talking. When you see pairs where one student is not talking, observe, inquire, and study that situation. Like an observant scientist, your goal is to determine what is blocking that student from participating in the conversation.

2. Brainstorm what makes a good partner (see Fig. 2). Students can come up with great lists of positive partner behaviors. These can serve as an anchor chart throughout the school year. [4]

3. Build the norm that “everyone works with everyone” (another Daniels/Steineke-ism). One way to do this is to ensure that students work with as many different pairs as possible during the initial weeks. To do this, I change the seating chart every day for the first couple weeks, simply taking the index cards we made on the first day of school and placing them around the room before the students walk in. This sometimes becomes frenetic for me as I race to do it between classes, but the end results are worth it because, at the end of a few weeks, A) my students are better acquainted with one another, B) I'm more aware of how my students mix with their peers, and C) students have internalized the fact that, like my mentor Gerome Dixon used to say, my classroom is “my house,” and as such there are some small decisions (e.g., where we will sit) that I'll take care of each day.

4. Explain why the conversational skills practiced in Think-Pair-Share are far from just schooly stuff. Think-Pair-Share makes us better not just at learning, but important situations like interviewing or dating. These are skills, then, that we all want — and though the work will be hard, it will also be fun as we do it together this year, day in and day out.

Because in our classrooms, speaking and listening will not be the forgotten language arts. May you and your students flourish this year.[hr]

Footnotes:

- The other 20 percent being the pop-up method for debates or discussions.

- You'll notice I don't include “engaging” as a criterion for strategy selection. This is very intentional: my goal is for students to be engaged with the content of my curricula and the questions through which we're exploring that content. When I begin making strategy decisions based on “What will be the most engaging strategy?” I'm already on the rabbit trail. Successful people aren't engaged by strategies; they are engaged by learning. I want my students to be successful, and as such I want them to work all year on realizing that what makes a class engaging isn't how we're learning, it's what we're learning and the curiosity that we as learners bring to that content.

- I explain my Call to Attention routine in the School Year Starter Kit, which costs a buck and exists to support the costs of running this blog. Get it here.

- Steineke and Daniels' book is essentially a set of 35 lessons, and it includes slideshow files like those in the margin of Figure 2. I wish this book had existed when I was starting out as a teacher.

Thanks to John Strebe for helping me see the power of Lyman's Think-Pair-Share — I probably learned about it in my undergrad years but completely forgot it — and to Frank Lyman himself for daring to put forth a strategy as simple as Think-Pair-Share. Finally, in case this article didn't make it obvious, I am thankful to Nancy and Smokey for their great book, too.

Matt Jones (@opttobegreat) says

Love the whole post, but particularly the distinction between engaging with the learning vs. the strategy. This is an extremely important point to make in a time when so many products and apps claim to increase student engagement, but with what? Actually learning or the app itself? Thanks for the important reminder!

davestuartjr says

Thank you, Matt! That was one of my favorite ‘Aha’s when writing this post.

Diane -- Kansas City says

Please remember to provide supports to English language learning students when utilizing strategies such as Think-Pair-Share. Depending on where a student is in his or her emerging bilingualism, they may appear to you or to a classmate to be disengaged, when it may actually be a language barrier. In this case a teacher might consider one or all of the following:

* Discreetly provide an index card with two or three sentence frames to such the student before the pair-share

* Encourage the emerging bilingual student to share/teach words from his or her language to their pair-partner

* Consider how the strategic use of images can help support conversation for emerging bilinguals

* Keep in mind that many (but not all) people experience a “silent period” while incorporating an additional language into their linguistic ability. Know your students well enough to understand if a particular student who “looks” disengaged or “lacking” social skills might not actually be absorbing an entirely new way of expressing their knowledge and the cultural expectations of a U.S. classroom.

davestuartjr says

Powerful comment, Diane — thank you for sharing this and I hope it helps many readers. Cheers!

Lynsay says

Thanks so much for this. We use this strategy all. the. time. in our hallway (I’m blessed to have an incredibly aligned, talented, and hardworking 9th grade hallway), but I think we take too much for granted. We aren’t doing enough teaching about how to make them excellent– we’re mostly scanning to make sure that all kids are on task and listening for the keywords of the content. Your bolded list will be helpful for quality control, and your investment re: real life situations like interviewing and dating seems authentic. I’m excited to teach and sweat these in the coming weeks!

Guillermo says

That is a powerful tool in learning