Note from Dave: This summer, our colleague Lisa Van Gemert reached out to me to tell me about a new book she had written. I've always appreciated Lisa's work, and I was particularly eager to share it in this case because it's 100% in line with what I believe to be the best avenue for improving students' enjoyment of learning and equitable long-term flourishing outcomes in our schools: a generous, knowledge-rich curricula that gives our children access to the many wonders of the world and its precious disciplines.

But! Summer became August, and August blurred into September, and October rushed by, and here we are in November with me finally sharing with you Lisa's simple, powerful method for helping students master the big idea words that are so fundamental to strong, disciplinary thinking.

Very kindly, Lisa was willing to let me publish the third chapter of her book, which lays out the way in which she helps students to master academic vocabulary.

How to Use the Concept Capsule Method

[What follows is an excerpt from Lisa Van Gemert's book, Concept Capsules: The Interactive, Research-Based Strategy for Teaching Academic Vocabulary, which you can get as a paperback through Amazon or a printable, downloadable file through Gumroad.]

Let’s talk about how the Concept Capsule strategy works in a classroom. It’s so straightforward that it seems impossible that it could be effective (it is, though, I promise!).

In a nutshell, you choose critical vocabulary, explicitly teach it, review it often in

ways students enjoy, use it regularly, and quiz it frequently.

I’ll share the details of each of those things below, but this is the basic strategy.

While there is no one “right” way to do it, here is my general plan:

1) Introduce: Share between three and five new Concept Capsules per week (for a

total of about 80)

2) Review: Play at least one review game or activity per week

3) Quiz: Give one quiz per week that includes all of the introduced Concept Capsules

as possible quiz topics

4) Include: Include Concept Capsules on every test and quiz, even if it’s only one

question

5) Use: Use them in conversation frequently

6) Test: Give at least one test per semester over all of the Concept Capsules

This constant, integrated approach works with what we know about the neuroscience of learning to increase the change that the vocabulary is being valued by the students’

brains (see Chapter 10 for more about why the quizzes and tests are so important).

Time Commitment

Most educators are concerned about how much time this process takes. It doesn’t matter how great something is if you don’t have the instructional time to make it happen. Luckily, that’s not an issue with Concept Capsules.

The introduction and initial review take about ten minutes per Capsule.

Because you are already giving quizzes and already testing, it’s does not take extra

instructional time to include some Concept Capsule questions. Every test or quiz I give has Concept Capsule questions on it. If the quiz is short, there may be only one.

If I’m assessing student writing, I will integrate a Concept Capsule into the prompt. I could ask them to use a simile or personification in the response. So, there is not necessarily a question. Rather, there is an application.

Using them in conversation takes no extra instructional time.

The review activities range in time, but they are typically under twenty minutes.

The test at the end of the semester is the thing that takes the most time, and it’s only

twice a year.

So for the things that do take time, where do I find that time?

I use what I call “dead zone” moments to practice Concept Capsules. These are the

moments that can be hard to fill with quality instruction. Every classroom is different, but they often arise when you finish an activity and don’t have time before the bell to

start in on another. They arise when you have a lot of students absent and don’t want to move on without them. They can happen when you planned an activity and there’s a tech breakdown, making the planned activity impossible. Concept Capsule activities, quizzes, and tests also make excellent emergency sub plans!

Concept Capsules lend themselves beautifully to distance learning. When we are getting students used to online learning and our mannerisms with it, it’s helpful to have content that they are familiar with. This ensures that we do not get confused as to what is causing the student difficulty, the tech or the content. Concept Capsule introduction and review are perfect for this. As we get progressively more blended in our classroom instructional modalities, their flexibility will become even more beneficial.

In full honesty, I find that Concept Capsules save me time overall. They increase student achievement, meaning that I have fewer students needing to move to higher levels of RTI. There’s a spillover effect here, because the increased self-confidence that comes from success with Concept Capsules often means that students improve in other areas in the class as well. They make acquisition of material much faster.

The real time burden is creating them, and that is done outside of class. (See Chapter 4 for the details on that process.)

Have I persuaded you that you really do have time for them? I hope so!

Step 1: Introduce

The ancient saying, “Well begun is half-done,” definitely applies here.

The full explanation of how to introduce Concept Capsules to students is the entirety of Chapter 5 because it’s so important.

They must be introduced from a place of encouragement and even excitement. If your attitude is, “Well, here’s one more thing they’re expecting me to do,” your students will feed off that attitude. It’s contagious. Consider instead this attitude: “I have found the secret sauce, so get out your little word hamburgers, peeps, because we’re gonna douse ‘em!” As educators, we often underestimate how much we are the barometer. Students read us like they do the weather.

When I explain each Concept Capsule, I make sure to include some anecdote about why I chose it or a cautionary tale about a student who ignored it to his/her peril. I often will try to create curiosity about the word. Curiosity drives learning, so if I can get them to wonder, I’m half-way there.

I pass out the Capsules, and then we discuss them. I usually take about 5 or 6 minutes to discuss each one. I focus on the definition and sample test question at this time. The extension/interest section below the definition is often explored by the student on their own. Occasionally, depending upon what I included, I will discuss that as well. The section at the bottom is not discussed in class. It is for students to complete on their

own. It’s where they practice, connect, and explore.

They keep them in a section of their binders (unless they’re digital, of course).

Once they have been introduced to a Concept Capsule, they know it is always fair game. It doesn’t matter if they received it in August, we will still be working with it in March.

I do not grade Concept Capsules. They are for student use. There will be plenty of

opportunity for assessment. The Capsules themselves are not a Gotcha! If a student

wants to check an answer with me from the sample test question or share their extension work with me, I’m happy to do that. (Note: I’ve created keys for the Concept Capsules included in the book.)

Step 2: Review

Review games and activities are truly the heart of the Concept Capsule strategy. Chapter 11 goes into 26 of the different games I use and explains the neuroscience of why review is so important. If you are not willing to review, this strategy will not work for you. It is the heart and soul of the method.

After the initial introduction (see Chapter 5 for exactly how to do that), the key idea is that you keep the Capsules in play. Imagine a baseball team warming up, throwing the ball around the bases from player to player, constantly in motion. The ball never really lands anywhere.

That’s how Concept Capsules should be: once they’re in play, they never get put down. We keep them in motion to keep them front of mind.

For the review to be effective, it cannot be a “gotcha.” It’s low-stakes, enjoyable review that is designed to have students feel as successful as possible.

The review activities do not need to be time consuming, but they need to be frequent. It’s far better to have frequent, short review experiences than a single, extended experience. In addition to being more effective, it also makes it easier to carve out time for.

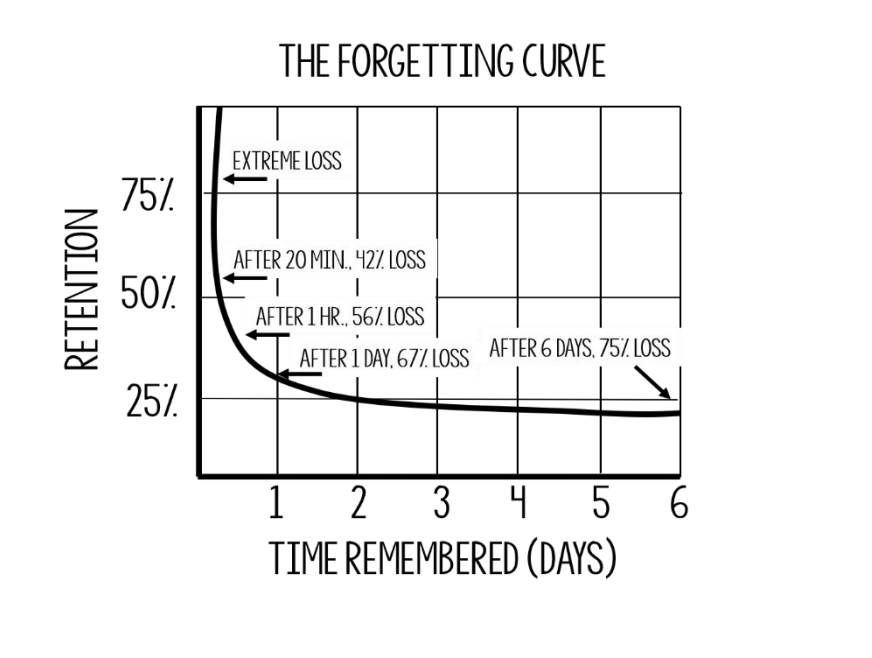

The research on this idea has been going on a long time. In the 1880’s, Herman Ebbinghaus conducted a series of experiments (on himself!) to test how quickly people forget learned information. He found that the rate of forgetting was shocking. When plotted on a graph, it looks like this:

This type of forgetting is called “transience.” Ebbinghaus believed that the key to

correcting this curve was repetition. With repeated exposures at optimal times, recall

improved dramatically. That curve looks like this:

If students have quality review activities that closely follow the initial instruction, the curve is shockingly different. Ebbinghaus believed that every review experience meant you could space further review farther apart (so you need to review less and less frequently as you move on). You do, however, need to review close to initial instruction.

That’s the opposite of what most teachers do.

What most teachers do is teach something, assign a practice assignment, perhaps review that assignment, and then move on until there is a test. Then, they give a review of all of that learning.

With Concept Capsules, we review frequently, and we begin the review immediately.

After the introduction of the Concept Capsule, begin reviewing right away. If students have already had a few Concept Capsules introduced to them, I’ll take another few minutes and play a review game, including the new Capsule in the game. If this is the first Concept Capsule, practice with just this one by using simple questioning.

For example, if the Concept Capsule is “integer,” the teacher would say something like:

- If I say I’m 11 ½ years old, am I using an integer to describe my age?

- If I had $6 and I owe somebody $9, is the amount I need an integer?

- If gas costs $2.39 a gallon, how much more would it have to cost for the price of gas to be an integer?

- I’m a negative whole number. Can I be in the integer club?

- I’m a positive decimal number. Can I be in the integer club?

- Take your age and divide in half. Is that number an integer?

I often ask students to come up with a similar question. I then use those questions to review the next class period (if they’re useable). Students love seeing their own questions on the quiz, and not just because they know the answer!

Step 3: Quiz

The quizzes are as important as the review because they are part of the review process. Chapter 10 will dive more deeply into the neuroscience of quizzing and why it’s so important. Here, I will discuss what it looks like in class.

Once a week, I will have quick quizzes over the Concept Capsules. These are usually five questions. Sometimes all five questions will be over the same Concept Capsule! The key is that all introduced Concept Capsules can be included on the quiz, not just the ones introduced that week. Once you’ve learned a new term, that term is fair game for the rest of the year.

These quizzes make excellent sponge activities (bell ringers).

If you prefer, you can tack the questions on to another assessment you’re doing, but I have found it’s best to have these separate little quizzes as well as including Concept Capsule questions on other assessments.

When I give separate, frequent little Concept Capsule quizzes, I allow students to gain confidence, focus on the vocabulary in isolation for a moment, and build their grades up. Most students do very well on them, so they become a boost in a number of ways.

I do not count the grade for every quiz in isolation. That floods the gradebook and makes the quizzes too high-risk. If there are only five questions, even missing one earns you an 80. Instead, I enter the number correct for each quiz in the gradebook. Once per grading period I will add up all of the questions and give an overall score. If there were 6 quizzes of 5 questions each, I have 30 possible questions. I add up the correct answers and divide by 30 to get a single Concept Capsule Quiz grade that is counted. With digital gradebooks now, it’s easy to do that, but before my gradebook could do it, I would use a spreadsheet to calculate that for me.

Occasionally, I will also give a longer Concept Capsule quiz, so that students can practice a lot of Capsules at the same time. (I share an example of one of mine in Chapter 10).

This is not prescriptive. You are free to count the quizzes however you like. I have found that this method works well for my students, but if you’re someone who needs to find more things to grade, you could count each one individually.

Step 4: Include

In addition to the dedicated quizzes, consider including one or two Concept Capsule questions on the other quizzes and assessments you give students. Because I want the assessment grade to reflect those objectives, I give these questions as bonus questions. If I forget, my students will ask about them. They look forward to those bonus opportunities!

This accomplishes two things: it keeps the Capsules front of mind, and it keeps students’ attitudes about the Capsules positive. They see them as a way to gain extra points.

Another benefit of this is that it provides that frequent review that we learned from Ebbinghaus that we needed.

Feel free to recycle questions. You do not need to come up with 4,000 quiz questions!

Whenever I’m writing a quiz or assessment, I will have at least one or two moments where I need to pause and think of how to write the question. While I’m thinking, I’ll just add in a Concept Capsule question. That way, it doesn’t feel like an extra piece. It’s just part of how I draft the quizzes and assessments.

Students often write great quiz questions, so I always have it as an option on the “What to do if you’re done” list for early finishers. If I use their question, I give them a bonus point (in addition to the point they’ll get because they know the answer). Once they understand the process, you may never write another question again!

Step 5: Use

When I first became interested in the research behind vocabulary instruction in my pursuit of the vocabulary Fountain of Gold, one of the techniques that came up over and over again seemed too simple to be effective: use the words.

Really? I spent $28 on this book, and all you have to tell me is to use the words?

Yes, really.

It turns out that it’s pretty common for teachers to give direct instruction about words but then never use them again except when they test them. They may occasionally say, “Oh, that’s one of our vocabulary words!” but it’s not a consistent practice.

The research is clear that we need to be immersed in a word ocean, rather than trying to learn by catching a random drip. How do you do that?

With Tier II words, it’s easier to do this than it is with the Tier III words that form our Concept Capsules. It’s far easier to find opportunities to use “egregious” in the classroom than “constitutional monarchy.” Unless, of course, you’re homeschooling in Buckingham Palace.

Some groups of words lend themselves more easily to infusion into regular discussion. If your students are learning weather words or different types of clouds, a simple check in on the day’s weather is relatively simple.

When your Concept Capsules are not naturally going to come up in conversation, the techniques that work best for me are analogy and casual reference.

I look for analogies to the Concept Capsules we’re using. To stick with the constitutional monarchy example, I look for things we’re talking about that could be even the most tangential analogy to the Concept Capsule. I form questions that allow me to discuss the topic at hand, using the analogy of the Concept Capsule I’m targeting. So, I’d say, “How is your textbook like a constitutional monarchy?” or, “Constitutional monarchy is to democracy as pencil is to what?” The crazier, the better. Their responses will shock you.

I also look for opportunities to throw it out into regular conversation, asking questions such as, “How is our school district like a constitutional monarchy?”

It doesn’t take long for this to become second nature. You may even find that your students begin to make suggestions, as well.

Step 6: Test

Once a semester, I give a big Concept Capsule test. As with the quizzes, my students look forward to these as confidence and grade boosters. That always surprises me a little bit because these tests are not easy.

They should resemble as closely as possible the way the students will encounter the term on the most difficult assessment they will see. Try to make these questions more about application and evaluation than knowledge or understanding. The tests are where you pull all of the stops. It’s where the rubber meets the road. Insert your favorite cliché about really showing what you’ve got here. That’s what these tests should be.

Frequently, students will race to come tell me how “easy” a big test (like an AP test or our state assessment) felt to them because they had total word confidence. Here’s the truth: to the brain, there is no such thing as “easy” or “hard.” There is only “familiar” and “unfamiliar.” By using the Concept Capsule method, I ensure to the greatest extent possible that my students enjoy a sense of ease so their abilities can shine through.

Wrapping Up

My hope is that by sharing exactly how I implement the Concept Capsule method, you will be able to have a vision for possibilities of how it could work in your class. The method is tried-and-tested, so I would make sure to give it sufficient time to get a feel for it before you start adjusting. Adjust too quickly, and you run the risk of leaving out the step your students need most.

That said, there are no hard-and-fast rules. I made up the method, and I’m giving you permission to adjust it any way that works for you.

Lisa's book, Concept Capsules: The Interactive, Research-Based Strategy for Teaching Academic Vocabulary is available now. I prefer the digital version because of its easy printability for my classroom — you can get that here. There's also a paperback version on Amazon — that's here.

Leave a Reply