Dear colleague,

Someone asked me at a PD recently, “What's the most important teacher book you ever read?” At the time they asked me, there just happened to be a copy of Jim Collins' Good to Great sitting on a table nearby. I picked up the volume and I said, “Let's go with this one.” (It's a great question because there's no one book; there are a generous handful.)

To be clear, Collins' book is not a teacher book. Many of the books that have most helped my career have not been teacher books. This is probably because non-teaching books are laden with analogies, and analogies are essential to learning new things. (See Willingham's Why Don't Students Like School? for the cognitive science behind analogies.) By learning about something unrelated to teaching, I end up gaining clarity and insight into the complexities of teaching. Counterintuitive, but I've experienced it so consistently that I almost take it for granted.

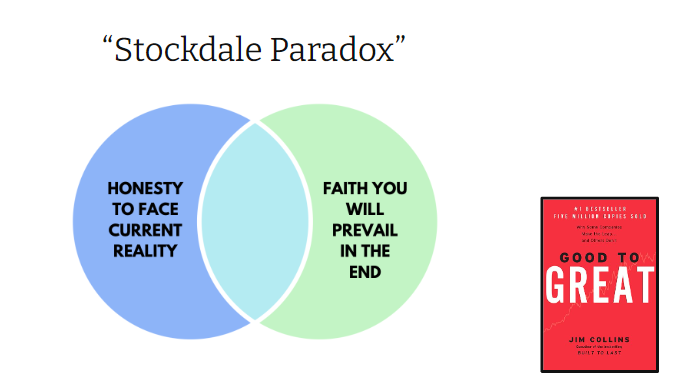

One reason Collins' book is so good is because, in it, he introduces the Stockdale Paradox. The story goes that Admiral James Bond Stockdale (yup, that's his real middle name — unfair) was a prisoner of war during Vietnam, and he noticed a pattern in prisoner survival rates. Interestingly, it wasn't the optimists or the pessimists who proved most resilient. If an optimistic POW was constantly telling himself that he'd be freed any day now, he eventually lost heart and perished. And if a pessimistic POW was constantly convincing himself he'd never be freed, then sure enough — he lost hope, too.

The folks who survived the best were folks who held two contradictory truths in mind day after day.

- On the one hand, they were relentless in confronting the brutal facts. They were rigorously honest about life as a POW, how dire and terrible and tortuous and bleak it was. Life as a POW was a living nightmare. They didn't hide from this, but instead confronted it regularly with their minds.

- But on the other hand, they held an unwavering faith that, eventually, they'd be freed. They reminded themselves that folks were working to find them, that their release would come eventually.

For Collins' book, he used the Stockdale Paradox to explain how the “good to great” companies handled challenging times. By holding on to a deep belief that they'd eventually succeed while simultaneously confronting harsh realities, they were able to make the necessary changes and persevere through adversity. It was this paradoxical blend of realism and optimism that proved crucial to long-term success in the companies Collins spends the book examining.

Once you start looking for this dynamic, you see it everywhere.

- One example: In the famously effective AA program, participants begin by acknowledging their powerlessness over alcohol and the unmanageability of their lives (Step 1), and then move immediately on to cultivating a faith in a “power greater than [them]selves” that “could restore [them] to sanity.” Confronting the brutal facts (Step 1); cultivating an unwavering faith (Step 2). And then the rest of the program is basically do the kinds of things that help people return to sanity.

And for our purposes, colleague, the Stockdale Paradox provides us with a radically different approach to teaching than jaded cynicism or rose-tinted idealism. We face the brutal facts daily — we don't shy away from them or pretend they're not there. My blog and books are filled with brutal reality. But one reason I'm proud of my books is that, at the same time, they're filled with an unwavering confidence in the goodness of an education, for all students.

And so then, what do we do? We operate from both realities. We engage with both. And in doing that, we become these otherworldly kinds of creatures: teachers who are both realistic and idealistic. Because both views are needed to do the work well and with peace.

Next time, I'll push this idea on top of a common problem we face: students who don't Value school.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

P.S. I made a short video about this topic a while ago; you can see it here.

Kara says

This hit me especially today. I am an instructional coach in a district facing an operational referendum in the spring. While I am hopeful that my position will be there next year, I am also planning for what happens if it isn’t. I am designing new courses (because if I go back to the classroom, I want it to teach what I want to teach) while I search for other jobs.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Sounds like you are balancing the paradox well, Kara. Hang in there.

Hang in there.