Since The Will to Learn came out, I've worked with dozens of faculties and teacher groups on the material and continued to practice its ideas and strategies in my own classroom. What I've found is that even the short list of 10 strategies I write about can be pretty overwhelming. It's too much to focus on at any given time. So towards the end of the 23–24 school year, I started to ask myself questions like:

- “Which of the strategies have the greatest impact?”

- “What smaller list of the 10 would achieve the largest improvements if others were removed?”

- “How do the strategies overlap with one another, and how might I use that overlap to reduce the number of things I ask teachers to try when they are getting started?”

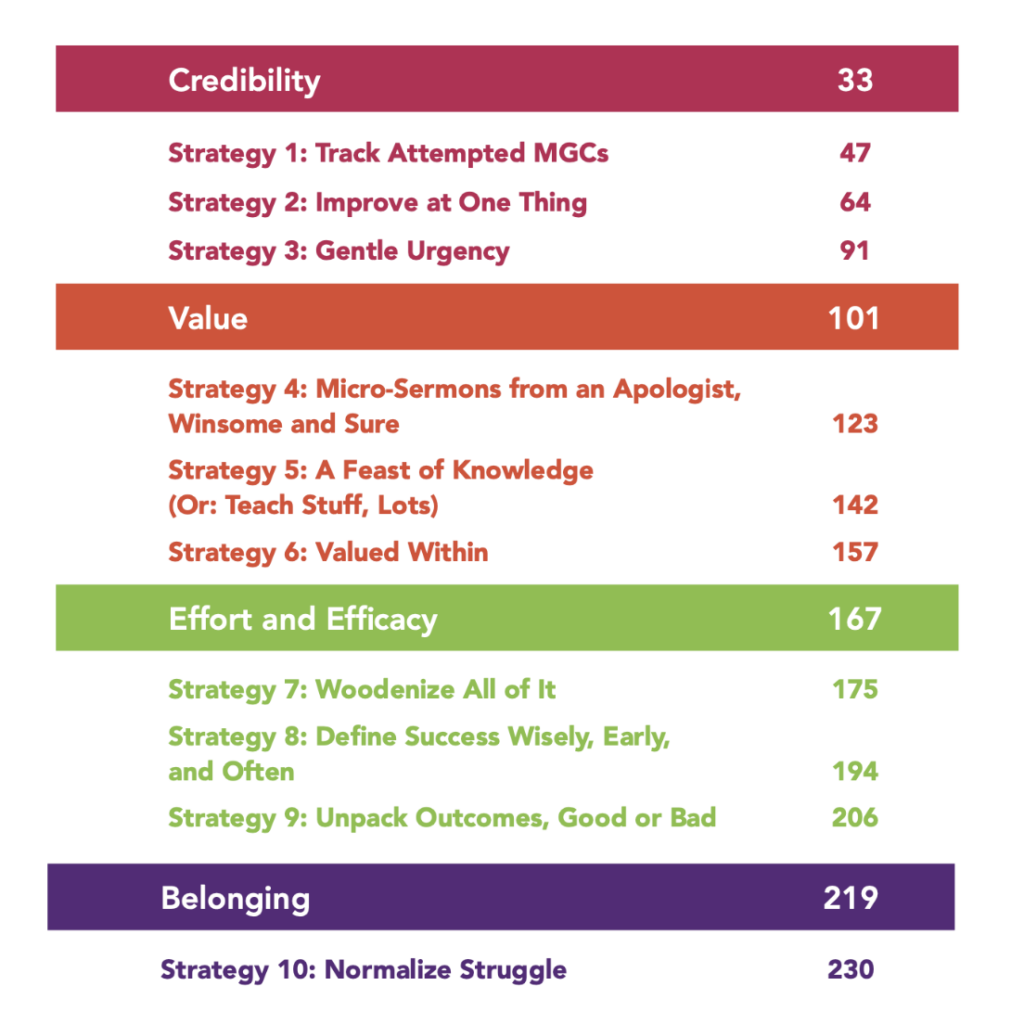

Before I share my answers with you, let's do a quick overview of the 10 strategies in the book.

An Overview of the 10 Teacher Strategies in The Will to Learn

Here's a screenshot of the table of contents from The Will to Learn, and below this are brief descriptions of each strategy as well as where you can learn more about each one.

- Strategy 1: Track Attempted Moments of Genuine Connection (MGCs). These are brief (30–60 second) interactions with individual students, during which you attempt to make a student feel valued, known, and respected. You keep track of these attempts on a clipboard.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 47-63 in The Will to Learn, pp. 30-32 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 2: Improve at One Thing. This strategy is central to all of my writing. Even though I write about quite a few things, I'm only ever pushing myself to improve at one thing at a time. Many of the tools and ideas I write about are at play in any given week of school, but I'm only pushing myself to improve with one tool or idea at a time. This focuses my efforts and yields faster improvement than distributing my improvement efforts too thinly and broadly.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 64-90 in The Will to Learn.

- Strategy 3: Gentle Urgency. This is all about using class time well and signaling to our students that class time is sacred, while at the same time we are human beings who won't always get it right and sometimes need rest.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 91-100 in The Will to Learn.

- Strategy 4: Mini-Sermons from an Apologist Winsome and Sure. These are frequent, brief (30–60 second) “sermons” in which we as teachers explain why the work we are doing is valuable. During these mini-sermons, we demonstrate that we respect our students' skepticism about the Value of learning while at the same time casting a confident vision for the full-spectrum Value of what we're doing.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 123-141 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 5: Feast of Knowledge (Or: Teach Stuff, Lots). The research is pretty clear: the more we know about a subject, the easier it is to learn about that subject and feel motivated in doing so. The whole idea with this strategy is that learning things ought to be presented as a feast, not a chore. By using simple methods like teaching all you know, incorporating knowledge-rich sources, and helping students memorize “sets of knowns,” this strategy brings knowledge-building to the foreground and cultivates Value as it does so.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 142-156 in The Will to Learn or Chapter Three of These 6 Things.

- Strategy 6: Valued Within Exercises. These are a set of moves designed to guide students to create their own reasons for valuing school. They help students habituate the life-critical task of valuing something for their own reasons rather than the reasons of others. Students need guided practice in generating Value for the work of learning within themselves, just as they need adults who model this Value for them (Mini-Sermons).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 157-166 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 7: Woodenize All of It. In this strategy, we seek to effectively teach, model, and reinforce every learning-conducive behavior that we expect of our students. The strategy is named after legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden, who famously began each basketball season by teaching his players how to put on their socks and shoes. This strategy is all about making effective effort clear for all of our students.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 175-193 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 8: Define Success Wisely, Early, and Often. Most students do not have a clear or helpful idea of what success in school looks like. In this strategy, we seek to communicate our vision of success to students and help our students generate and reflect upon their own definitions of success.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 194-205 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 9: Unpack Outcomes, Good or Bad. This strategy is all about pointing our students' attention toward wisely interpreting how their learning is going. If we don't do this, students are likely to make maladaptive interpretations of both bad results (e.g., “I did bad on the test; I'm stupid”) and good results (e.g., “I did good on the test; I'm smart”).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 206-218 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

- Strategy 10: Normalize Struggle. The thing with struggle (e.g., nervousness in public speaking; stress about tests; difficulty writing; self-consciousness when exercising in Phys Ed) is that students often interpret it as something unique to them. They then take this interpretation and form a devastating and growth-halting conclusion: “I'm uniquely ill-suited to the work we do in this class.”

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 230-242 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

How to Reduce the List Without Losing Too Much

Now let's go about reducing that list from 10 to as few as we can without losing something critical. Our goal is to make the approach even more streamlined than how it's presented in the book, so that we can increase the odds of us actually practicing these things in our classrooms.

- Moments of Genuine Connection (MGCs) – These have to stay because they develop relationships in the most efficient manner possible. Relationships are important because they make the job richer, more rewarding, and just possible. Plus, MGCs cultivate Credibility (by signaling Care), and Credibility is the bedrock for cultivating all the rest of the Five Key Beliefs.

- Improve at One Thing – This can go because, by getting rid of it, we'll actually be doing it. By giving ourselves fewer strategies to focus on, we can get better at each one faster. And that's pretty much the whole idea with Improve at One Thing. By “getting rid of it,” we're actually doing it.

- Gentle Urgency – This is important because it signals to students that while we value their humanity (gentle) we are also passionate about the best use of class time (urgent). But we'll signal our valuing of their humanity through MGCs as well, and we'll signal that we are passionate about our class time through mini-sermons. So we can get rid of this one if we're going for a minimalist approach.

- Mini-Sermons – These have to stay because they accomplish a few objectives. First, they signal to our students that we are passionate, and Passion is one of the CCP signals of Credibility. Second, they are very difficult and, therefore, require extra practice of the teacher in order to become good at them. Third, they are brief — 30–60 seconds — so they don't take much time. Fourth, in crafting and delivering these mini-sermons, we remind ourselves about why we love what we teach, and we end up creating richer Value in our own hearts as we seek to cultivate in the hearts of our students. And fifth — that's right, there are so many reasons to keep this one — as we increase the quantity, quality, and creativity of the mini-sermons we deliver, we end up getting through or around or over or under the inner walls so many of our students have built up against Valuing the work we do in our classes.

- Feast of Knowledge – This one is hard to get rid of because knowledge is so integral to everything our students experience and are able to do. I mean, the whole idea of the strategy is that human beings are rarely motivated to work at learning something they know nothing about. Attention, effort, and care are finite resources, and I have to use an extra portion of each of them if I'm going to work at something I'm currently ignorant of. Buuuuuuuut putting on a feast of knowledge each day has taken me years of practice, thinking, and tinkering. It's required a total paradigm shift for me in terms of what I teach and why I teach it. (See Chapter 3 of These 6 Things for a deep dive into that.) So that kind of goes against the minimalist approach we're after in this blog article. It goes.

- Valued Within – This one can't go because of how powerfully it complements Mini-Sermons. When you do regular Mini-Sermons plus regular Valued Within exercises, you're doing a full court press on the Value belief.

- Woodenization – This one can't go because it makes effective effort clear. Droves of our students have tried working hard in their school career, only to see that work amount to nothing. When we teach them how to work hard and smart, we see massive boosts in all areas of the Five Key Beliefs. Of all the strategies, it's the most work; of all the strategies, it saves the most work in the long haul. It stays.

- Define Success – This one can't go because so many of our students suffer for lack of a clear idea of what success is. When they lack a quality vision of success, they borrow lesser visions from others or from the culture, and this usually looks like “get good grades” or “pass enough classes to graduate” or “go through the motions of school so I can get a good job.” The good news with this one is, it doesn't take a ton of work to do it better than 99% of teachers in the world.

- Unpack Outcomes – This one also can't go because of how tricky school outcomes can be. Why are they tricky? Because they are ambiguous. What does this test result mean? Is it success or failure? Can I learn anything from this essay feedback I've received? If I don't guide students in asking these questions, I find that they won't tend to ask them and will instead draw unconscious conclusions that aren't helpful to the cultivation of the Effort and Efficacy beliefs. Just like with the preceding strategy, there's good news here, too: this doesn't take a lot of work, just a bit of teacher clarity and intentionality.

- Normalize Struggle – Of all the strategies, this one is the simplest. It only takes 1) me being aware of how alienated students feel when they are struggling, how many of them struggle with worries about being “the only one” who struggles like they do; 2) me creating situations in which I can prove that these struggles are normal; 3) rinse and repeat. It stays.

So, I went from 10 to 7. Not much of a reduction, right?

It seemed like that to me at first. I was frustrated. C'mon, Dave — cut two more, make it a 50% reduction.

But the reason I didn't is because, by removing the three that I did, you get efficiency and focus gains that exceed the simple three strategy reduction.

- MGCs are simple, brief, and repeated attempts to show each student you care. These enhance Credibility and Belonging very effectively.

- Mini-sermons are simple, brief, repeated attempts to creatively and confidently explain to your students why they're doing the work they're doing. These enhance Credibility and Value with as little effort as possible.

- Valued Within exercises are simple, brief, repeated attempts to get your students creatively and confidently deciding why the work they are doing matters. These cultivate Value in a way that lasts and in a way that places the work where it ultimately belongs: on the student's shoulders.

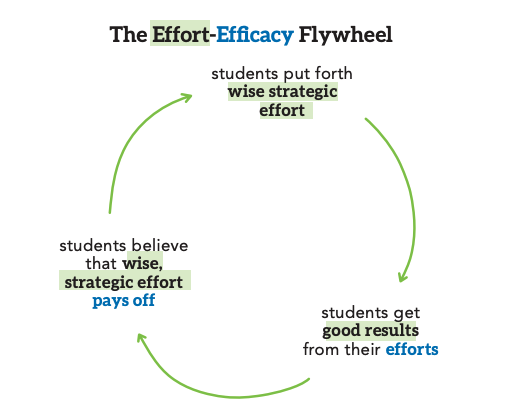

- Woodenization, Define Success, and Unpack Outcomes are an interconnected trio. They are designed to intervene at the three places where the Effort and Efficacy beliefs are made or broken:

- These three strategies work within the Effort-Efficacy Flywheel:

- When students work at learning, they need to be carefully taught, modeled, and reinforced on how best to do so. When I do this teaching (this Woodenizing), I also enhance my Credibility.

- As students are working towards an outcome, they need to have a clear and helpful idea of what the ideal outcome would be — that is, they need to Define Success. We can do that for them, and we can help them do that for themselves. Both teacher- and student-generated success are critical for a robust, helpful definition of success to form in the heart of a student.

- And as students get to the outcome — the test result, the project feedback, the essay rubric — we need to help them unpack their results in a way that spurs further hard work and success-seeking.

- And finally, Normalize Struggle is simple and efficient, too. By dealing with student concerns about “not fitting in” in a serious, compassionate, evidence-based manner, we cultivate both Belonging and Credibility.

So this school year, my recommendation is to play with just these seven tools as you seek to do something productive about student motivation problems in your setting. Use them not just in response to problems, but proactively, before the problems happen. It's in hope of supporting that proactivity that I've done the work you'll find via all the links on this article.

I really hope this helps.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Barbara Hale says

I’ve been reading The Will to Learn this summer and creating my own list of what to work on when school starts. I came pretty close to matching your list. I feel like I am on the right track. I had Woodenization on my list and I appreciate how you link Defining Success and Unpacking Outcomes with Woodenization and link all of those to Efficacy and Effort. I already work at Defining Success, but adding in the Unpacking Outcomes could be a game changer. Can’t wait to find out!