In the speaking and listening chapter of These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most, I argue that great classrooms can be built on just three speaking/listening structures:

- One for pair interactions (I use Think-Pair-Share)

- One for group interactions (I developed a tool called Conversation Challenge)

- One for whole-class discussions (I developed a tool called Pop-Up Debates)

When a teacher uses just three methods for speaking/listening in class, both teacher and students are able to rapidly acquire proficiency in the application of these methods. From that proficiency, excellence and enjoyment can be pursued ad infinitum.

- What Is a Pop-Up Debate?

- Common Questions Regarding Pop-Up Debates

- Is it really a debate?

- What's the teacher's job during a Pop-Up Debate?

- What are the three hurdles of Pop-Up Debates?

- What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 1 (public speaking anxiety)?

- What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 2 (speech delivery)?

- What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 3 (speech content)?

- What is the most common problem that comes up when using Paraphrase Plus with students?

- Do you ever record student speeches and let them watch themselves?

- Why are disagreements important in Pop-Up Debates?

- What does Pop-Up Debate look like in my classroom?

What Is a Pop-Up Debate?

The “rules” for a Pop-Up Debate are very simple:

- Every student must speak at least one time.

- Students may not speak more than twice, unless the teacher indicates otherwise.

- To speak, students simply stand up (“pop up”) at their seats.

That's it. When there's a lull in the debate, the teacher calls upon students who have not spoken yet. In this way, the teacher ensures that everyone speaks at least once.

Common Questions Regarding Pop-Up Debates

Is it really a debate?

In the technical and competitive senses, my Pop-Up Debates are not debates. They are argument-laden discussions where students bring evidence, logic, and reasoning to the prompt at hand.

Why call them debates then?

One reason is that students like the sound of a debate.

Another is that the word “debate” implies that there should be arguing going on, and that's very accurate for me. I want lots of argumentation happening during a Pop-Up Debate, because argumentation is the stuff of critical thought.

What's the teacher's job during a Pop-Up Debate?

The teacher has a lot of jobs with Pop-Up Debates, all of which I find enjoyable and manageable:

- Give students adequate preparation for the debate.

- This can be as simple as having them write a response to the debate prompt and have them pair-share their response before the debate begins.

- Teach, model, and coach students toward overcoming the three hurdles of Pop-Up Debates.

- I'll unpack these more below.

- When there's a lull in the debate, call on a student who hasn't spoken yet.

- It's important to forecast this teacher behavior prior to the debate so that students are not surprised by being called on.

- Address common student misbehaviors right when they happen.

- Side talk (students speaking quietly to people next to them while someone else is speaking) and cross talk (students responding to the popped-up speaker while the popped-up speaker is still speaking) are the most common problematic misbehaviors.

- Pop-up and participate in the debate to model key moves and dispositions.

- Moves can include Paraphrase Plus, aspects of PVLEGS, having fun with the debate, clashing with an argument respectfully, and whatever else I think the students could use an example of.

Though this may seem like a long list of responsibilities, I find that the more Pop-Up Debates we hold in my classes, the lighter the burden becomes.

What are the three hurdles of Pop-Up Debates?

At this point in my career, I've facilitated hundreds of Pop-Up Debates in both ELA and history classes, and I've heard from dozens of educators around the planet who have used this strategy in all kinds of classrooms. From all of this experience, I find that there are three common hurdles a teacher must carefully and passionately guide students through as they progress in their Pop-Up Debate skills.

- Hurdle 1: Public speaking anxiety

- Hurdle 2: Speech delivery

- Hurdle 3: Speech content

What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 1 (public speaking anxiety)?

Through years of experimentation, I've found a simple learning progression that helps students succeed at the first Pop-Up Debate of the year. (Success in the first Pop-Up Debate = I stood up and answered the prompt. Very simple.)

Prior to the first Pop-Up Debate of the school year, you need to take three weeks to get students used to speaking to the whole class. This is very simple.

For three weeks, guide your students in Think-Pair-Share exercises two to three times per lesson. This can be done after a warm-up, after an independent work segment of the lesson, or at the end of class. These Think-Pair-Shares can be in response to any prompt that you (the teacher) would like students to think about.

- Think mode, in my classroom, means writing it down. All of my students have a spiral notebook in which we can write things down. Any time I need them to write something down, I can just say, “On a fresh page of your spiral notebook…” Spiral notebooks are cheap during back-to-school season, and I always purchase a hundred or so each year in case students can't purchase their own. At my local store, back-to-school deals on spiral notebooks can be as cheap as 10 cents per notebook.

- Pair mode is just that — students share what they thought about with a partner. Keep pair sharing segments brief to avoid off-task behavior. While students are sharing, walk around to monitor, listen, and redirect as needed.

- Share mode is very important because here is where students are going to experience that, in this class, speaking for the whole class to hear is a normal thing. That means I have to call on students who don't have their hands up. When a student shares during Share mode, I check their name off of a printed class roster.

The goal during these three weeks of Think-Pair-Shares is for each and every student to share during Share mode at least one time. In all cases, students will have been prepared for being called upon, because they'll be answering a prompt that they wrote about (Think mode) and rehearsed with a partner (Pair mode). This establishes that public speaking is normal in this class and that it's safe.

So we do this Think-Pair-Share program for three weeks straight. By the end of the three weeks, every student has shared during Share mode at least three times — once per week.

During week four, you do the same thing, except you're going to transform a Think-Pair-Share into a Think-Pair-Pop-Up Debate. You don't forecast that a Pop-Up Debate is coming. Instead, after you give a prompt, have students Think about it (write it down in a spiral notebook), have them Pair share it, and then you say:

“All right students — today everyone is going to share their response to the prompt using something I call Pop-Up Debate. It is very simple. Everyone is going to share their response, and to share you simply stand up at your desk and speak. When you're done speaking, sit down. Only one person may go at a time. If you are not sure what to say, you may simply read what you wrote in your spiral notebook. What questions might you have? All right — let's go.”

When there's a lull in the debate (i.e., no one stands up for ten seconds or so), you simply call on a student who hasn't gone yet. As students are speaking, I keep my eyes mostly on the roster I'm keeping track with; when there's a lull, I call on students with an emotionally neutral voice. I'm giving no feedback, trying to make the event as low-stakes and “chill” as possible. My only goal for the first Pop-Up Debate is simple: everyone speaks at least once.

When everyone has spoken, I take a minute to do something VERY important: I ask the students to raise their hands if they felt “at least 1% nervous” during this debate. Most hands go up. I tell the students to look around and notice that nervousness about public speaking is the norm, not the exception. I say, “Anxiety around public speaking often makes you feel like you are the only one who's nervous. But the reality is, you're not. We'll keep working on this so you can gain comfort and confidence as the school year progresses.”

This is an important teaching move because it normalizes struggle (see Strategy 10 in The Will to Learn). When struggle isn't normalized in a classroom, many students will struggle with the Belonging belief. One of many reasons I love the Pop-Up Debate tool is that it gives my students proof that they Belong in my class.

For the sake of completing Hurdle 1, I try to follow Pop-Up Debate #1 with two more debates, as quickly as I can. If Pop-Up Debate #1 is on Monday, I may try to fit Pop-Up Debate #2 in by Thursday and then Pop-Up Debate #3 by the following Tuesday. The idea is that I want to quickly normalize public speaking in my classroom. During these first few debates, I may give students tips about how to handle public speaking nervousness (e.g., use notes) or stories from my own experiences being a nervous public speaker.

This simple progression is all it takes to get 99% of students participating during Pop-Up Debates.

- For more on how I help students overcome their fear of public speaking, see this in-depth article or pp. 218-221 of These 6 Things.

- For more on special cases where students persistently refuse to speak during Pop-Up Debates, see this article.

- For more on special cases in which students have a documented excuse from public speaking (e.g., 504 plan, IEP), see this article.

What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 2 (speech delivery)?

Once students are passed Hurdle 1 (public speaking anxiety), they are ready to start working on speech delivery. Typically, I don't address speech delivery until we've successfully completed three Pop-Up Debates. It takes about this many to get students used to overcoming their public speaking anxiety.

Once we get to the end of Pop-Up Debate #3, I ask students to reflect on what we did well as a class during our first three PUDs and what we could do better. Typically, they will reference problems with speech delivery (e.g., filler words, eye contact, monotone voices).

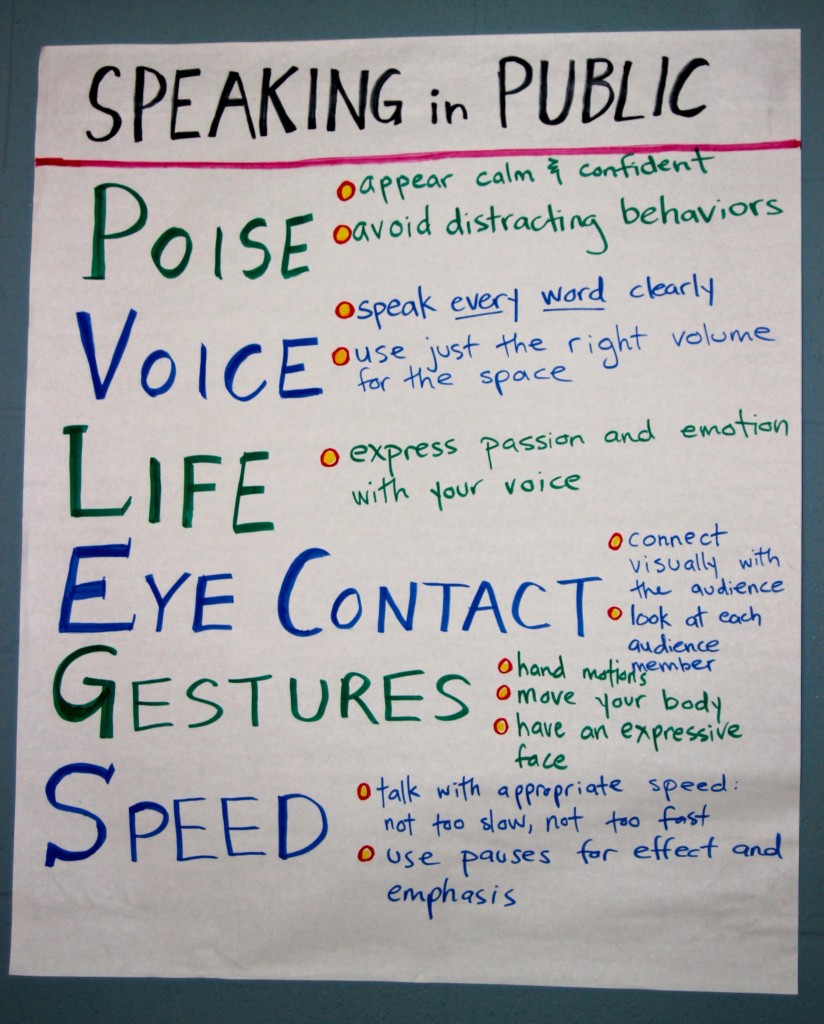

The only tool I use for teaching speech delivery is from Erik Palmer, a Colorado educator who created a blessedly simplistic and comprehensive acronym for addressing all problems in student speech delivery.

That acronym is PVLEGS.

I introduce these explicitly, taking notes on the document camera and having students take notes in their spiral notebooks. As we're taking notes, I give examples and non-examples. Once we've taken the notes, I ask students to select one element of PVLEGS in which they have a weakness and attempt to focus on improving that during our next Pop-Up Debate.

Hurdle 2 is much harder to cross than Hurdle 1 because PVLEGS is much more complicated than simply standing up while nervous. Students need lots of examples and non-examples; they need me to pop-up periodically and show them what PVLEGS elements look like; they need me to point out great PVLEGS elements as they are produced by their peers. It also helps a lot if they can see video of themselves speaking — more on that below.

- For a fuller treatment on PVLEGS, see this article, this video, or the book PVLEGS came from, Erik Palmer's Well Spoken.

- To examine exactly how I facilitated 20 Pop-Up Debates during the 23–24 school year, you can view this playlist of videos I created as I was teaching.

What are the keys to guiding students through Hurdle 3 (speech content)?

Working on PVLEGS will make a student sound much better, but it does nothing for improving the content of student speeches. For helping them with content, I use one simple tool: Paraphrase Plus.

Just like with PVLEGS, I introduce Paraphrase Plus to students via explicit instruction and note-taking. Paraphrase Plus helps me address lots of problems that come up with Hurdle 3 (speech content). These problems include:

- Silo speaking (i.e., students giving speeches that do not connect to what anyone else has said)

- Repetitive arguments

- Too few disagreements (more on this below)

Just like with PVLEGS, Paraphrase Plus is a tool that takes lots of practice, feedback, modeling, examples, and non-examples for students to get good at. You'll get as much out of this teaching tool as you put in to teaching it.

- For a more in-depth treatment of Paraphrase Plus, see this article, this video, or pp. 125-127 of These 6 Things.

What is the most common problem that comes up when using Paraphrase Plus with students?

One issue that's common is students thinking they've paraphrased someone when they've actually only alluded to that person's arguments.

They'll say, “Going off what Bryton said” or “I agree with Taylor.” This isn't paraphrasing.

When this happens, it's good to step in and remind students to use the sentence templates contained in Paraphrase Plus. If that doesn't work, I pop-up myself and model the use of the template for them.

Do you ever record student speeches and let them watch themselves?

The absolute best feedback I can provide my students as public speakers is letting them see themselves on video. Once we are well over Hurdle 1 (public speaking anxiety) and in the midst of working on Hurdle 2 (speech delivery), I often introduce the video camera.

I say, “Students, how many of you would love to watch a recording of yourself giving a Pop-Up Debate?” (No hands go up; many groans come forth.) “I know, right? Why do so many of us hate seeing ourselves on film? One reason is, when we're watching ourselves, we take an especially critical eye toward what we're seeing. Now, a lot of that self-critique isn't helpful — it's stuff like, ‘I sound stupid' or ‘I hate my voice.' What I want to do is teach you to be grateful for how much you're growing as a public speaker and at the same time identify areas where you can get stronger. So today, we're going to film the Pop-Up Debate, and tomorrow, I'll let you access the video during five minutes of class time so you can find your speech, watch how you did, and take notes on how you can improve.”

The first time I film students, it's a bit nerve-wracking for everyone. It's like hopping in a time machine and going back to that Pop-Up Debate #1 nervousness. This makes sense. But students quickly become accustomed to the presence of the camera.

Speaking of cameras, my setup is simple:

- I use my smart phone.

- I have this microphone attached to it. (It's a bit expensive; I made the investment because I intended to also use it for making my YouTube videos, and I've been very happy with it.)

Once I'm in my prep, I transfer the video file to a Google Drive folder that only my students can access. In the slide for tomorrow's lesson, I put a link to the Drive file. After students have had a chance to watch themselves, I remove the file.

Why are disagreements important in Pop-Up Debates?

One of the surest ways to make Pop-Up Debates more interesting is to encourage students to “clash” with the arguments of their peers. Oddly, we want them to disagree with one another because these disagreements add interest and promote student engagement and thinking.

Early on in the year, it's important to emphasize to students that disagreements are a good thing. I often tell students that the greatest sign of respect you can receive in a Pop-Up Debate is when someone argues with what you've said. This means that they were listening and that they've taken your words seriously.

It's also helpful to remind students of how bad many adults are at disagreeing well. You only need to scroll social media for sixty seconds to find examples of disagreements handled poorly. I like to emphasize to students that, when we practice disagreeing well in this class (i.e., when we use Paraphrase Plus to structure an argument against someone else's argument), we are doing something that most adults can't do. Teenagers love that.

What does Pop-Up Debate look like in my classroom?

In the 23–24 school year, I made a video after each of the 20 Pop-Up Debates that I facilitated in two of my classes. That collection of videos is available right here.

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: you get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply