In The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own, I lay out an approach to student motivation in which Five Key Beliefs can be influenced using just 10 basic strategies.

The tenth of those strategies is Normalize Struggle.

- What is it?

- What do you do?

- How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

- Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

What is it?

When students aren’t sure they belong in your class as they’re doing the work of learning that you’re asking them to do, then as soon as struggle comes, they’re likely to interpret it as a signal that yells, “This struggle is unique to you; you don’t belong!” This creates a hamster-wheel effect in their mind, making them hyper-alert to any other signals from your classroom that they don’t fit. And because Belonging signals can be so ambiguous, the hamster wheel is more than just a little thing; it biases student hearts to interpret ambiguous signals as more of the “you don’t belong” variety.

So here’s a strong fix: Create an environment in which struggle is both normal and productive.

What do you do?

The key with all the methods outlined below is that you're trying to make difficulty normal. This signals against tendencies in our students' hearts toward believing anti-Belonging things like, “This math work is hard for me and only me. Other folks don't struggle like I do; I don't fit in here.”

Step 1: Make difficulty normal — that is, something that's not unique to the student who is struggling.

Do this via the following methods.

Whole-class polling after something difficult

After a significant classroom challenge — in my room, that’s often our first Pop-Up Debate of the school year or our first test — I like to normalize struggle by asking my students a simple prompt: “If you felt at least one percent nervous during the preceding activity, please raise your hand.”

Every single time that I've done this after a whole-class speaking event like a Pop-Up Debate, upwards of 70 percent of my students have raised their hands. This is a powerful moment for the Belonging belief, and I cement it with a remark such as, “Now, class, look around you. Look at all the hands in the air. I want you to remember this. Anxiety is often a deceitful thing — it makes you think it’s only you who feels nervous. But look — look around you! It’s not just you. When it comes to speaking in front of peers, it’s most folks.”

Here I begin to smile.

“It’s those folks without their hands up that are the weirdos.”

And with a wink and a grin, I’ve sent a quick but powerful signal: Struggle is normal in the high-challenge realm of public speaking. You can do something similar after other activities, such as an assessment, a presentation, or a performance task.

The keys to success with this method include the following:

- Because your students (like mine) are broadly dispersed along a skill spectrum, make the initial challenge something that is inherently self-differentiating in its difficulty (e.g., a public speaking exercise or difficult pre-test). You want a majority of folks to be able to raise their hands afterwards, saying, “Yes, that was difficult.” And then you want to remind them that despite that difficulty, they came out on top (e.g., they participated despite public speaking anxiety or they previewed class content and the kinds of things they’d be learning this semester — despite not knowing everything, they learned).

- Provide adequate pre-experience practice and/or scaffolds so all students can experience a modicum of success. In my case, for the first Pop-Up Debate of the school year, this means that all of my students have participated in Think-Pair-Share on a daily basis and that I’ve called upon all of them to share to the whole class (during the share portion of Think-Pair-Share) at least once per week for three weeks prior to our first Pop-Up Debate.

- Be sure to define what the bare minimum of success looks like for the activity. In my first Pop-Up Debates, I tell students that success is simply standing up and participating at least once during the debate.

- Remind students after this experience of what they learned about the normality of challenge. I can’t stress this enough; you must reinforce for your students how to helpfully interpret this signal. They need this Belonging signal reinforced so they can attribute subsequent struggles to something that is normal for students rather than to something that is uniquely deficient in them.

Asking students to explain difficulty to younger students using a “student as expert” prompt

This is what I call “student as expert.” It’s a brilliant move that comes from the wise intervention strand of the social psychology research, spearheaded in part by folks like Stanford’s Greg Cohen and Greg Walton — two of the leading names in the work on cultivating the Belonging belief in educational settings.

Let’s look at how this works.

First, expose students to a few testimonials from students who have come before them. These can be direct quotes from previous students, or video testimonials, or your own anecdotal recollections.

In the testimonials, try to hit the following notes:

- “At first, I struggled with ________ and thought it was something unique to me.” (That last part is the key. Students need to hear from other students that they too thought they didn’t belong.)

- “Then, I realized ___________ was a normal struggle. I realized this when ___________ happened to me or when __________ said ___________ to me.” (Here you want to make sure the student describes the moment they realized it wasn’t just them.)

- “Once I realized that this was a normal struggle, I started [insert adaptive behavior] and began to see progress and enjoyability in my growth.” (Adaptive behaviors can include seeking help, attending study halls, or working more closely with friends.)

Then, ask students to explain to subsequent students why these stories make sense. In other words, enlist your current students as experts in helping subsequent students as novices navigate the ambiguity of struggle signals and interpret them as normal rather than as unique to them.

In the research, this powerful student-as-expert methodology is referred to as attributional retraining. It exposes students to:

- Folks just a bit older than them who are likely to sound much more believable than an “old person” (i.e., me)

- The chance to position themselves as experts and interpret their own experience with the struggle toward mastery as something that is normal rather than aberrant

The way I see it, attributional retraining is worth our time for a few reasons:

- The earliest step is where most of the labor is, as collecting testimonials takes time and intentionality on the part of the teacher, team, or school. But what’s brilliant here is that, once acquired, the testimonials from older students can be used again and again. Note that the testimonials have a certain pattern:

- “I once struggled in school and assumed it was a struggle unique to me.”

- “Then something happened and I realized it wasn’t just me.”

- “So then I started to reach out for assistance and was gladly given it.”

- The last part of the method places a student in the position of expert. Rather than receiving advice, they are responsible for giving it. This is a remarkably powerful way to shape belief; it is not, “Let me tell you why you belong,” but instead, “You tell me why you belong.”

- Experts aren’t just good for themselves, are they? They’re good for others, too — thereby enacting the Value power of prosocial purpose that I examine on p. 111 of The Will to Learn.

Let’s look at what this might look like in, say, a physical education class. Once students are dressed and completing their stretching routine, the teacher shows a three-minute videotaped interview of a student who previously took the class.

This student shares the following:

- They once thought phys ed wasn’t for folks like them because they couldn’t run that well.

- They came to discover that it was normal for phys ed students to experience this sense of anti-Belonging when their teacher told a story about a time in the teacher’s life when they were out of shape and had to retrain themselves to run a mile.

- The student had a breakthrough by focusing on what they could control in the phys ed space, and they realized that physical fitness is all about taking risks as an individual instead of comparing themselves to others.

Step 2: Make critical feedback normal with Greg Cohen's “magic feedback” method.

Some years ago, Stanford’s Geoffrey Cohen led a team of researchers to see if a certain way of framing critical feedback from teacher to student might improve student experiences in school. The intervention worked so well that Daniel Coyle later popularized it as “magic feedback.” The tweak was remarkable — “magic,” in Coyle’s words — in at least two ways: first, it was simple, and second, it was effective.

In the study, college students in the experimental condition were told, “I’m giving you this feedback because I have high expectations and I know you can meet them,” whereas students in the control condition were simply given the critical feedback without the magical line. Those who received the magical line were more likely to make revisions to their essays and indicate that they trusted their teachers (Yeager et al., 2014).

Now obviously, the feedback wasn’t a magic spell. My point in sharing it is not that you’ll photocopy a bunch of little lines like this and paste them into your Google Classroom response templates. Rather, it’s that you’ll internalize this idea that your students need to hear that you have high expectations for your students and that you know this particular student can reach those expectations.

Step 3: Make difficulty desirable — something they literally can't succeed without.

What we want here is to make it odd and unseemly to not seek some measure of challenge in a given class. Here are some methods that can help.

Creating a “do hard things” ethos in your classroom

The best way I’ve found for doing this is to frame secondary education as a worthy challenge for any youngster. I want to make “doing hard things” an ideal for my students, not a chore. I do this via the following:

- Hanging a sign above my whiteboard that reads “Do hard things.” — I periodically explain what I mean with this sign via Mini-Sermons (see Strategy 4 in The Will to Learn or this guide)

- Celebrating when a student overcomes a challenge — I want to highlight the moment in their mind as a beautiful, even transcendental experience

- Challenging common notions that my students or the broader culture hold regarding low expectations or comparing oneself to an arbitrary measure

Sharing stories of folks who link struggle to success

Our colleague Josh Cooper who teaches economics does this a bit differently, using a program he’s developed called “Motivation Mondays.” He likes to use this program in his general economics classes — the ones where students are there because the state requires it.

Each Monday, Mr. Cooper kicks class off after the warm-up with a brief video from former U.S. Navy SEAL Jocko Willink. The video is titled “This Is Gonna Suck,” and in it Jocko, in memorable style, elaborates on the idea that good things are often hard. “This advice,” Mr. Cooper says to his students, “is simple but not easy — just like a lot of others keys to success in life.”

The next week Mr. Cooper shares a video titled “Look for Work,” in which Jocko describes how he expects his SEAL team members to always be looking to improve. After sharing this video, Mr. Cooper will use this language with his students when they finish a task early.

A few weeks later, Mr. Cooper shares a Jocko video titled “Bust That Door,” in which the main idea is that when you are confronted with a hard task, the most difficult but best thing is to get started. Mr. Cooper likes to connect this to his students’ propensity for procrastination.

“Procrastination seems good in the moment,” he says, “but it typically doesn’t help you.” And so on he goes, using Jocko’s brief videos from Instagram to give his students a dose of perspective on struggle from a former SEAL.

Here’s why it works:

- Mr. Cooper’s prep for this is minimal. He keeps a running list in his e-mail inbox of videos that could work with his students.

- His source (Jocko) is novel to most students (this helps with Value) and inherently credible.

- He is dropping in these moments occasionally over time rather than relying on big chunks of class time.

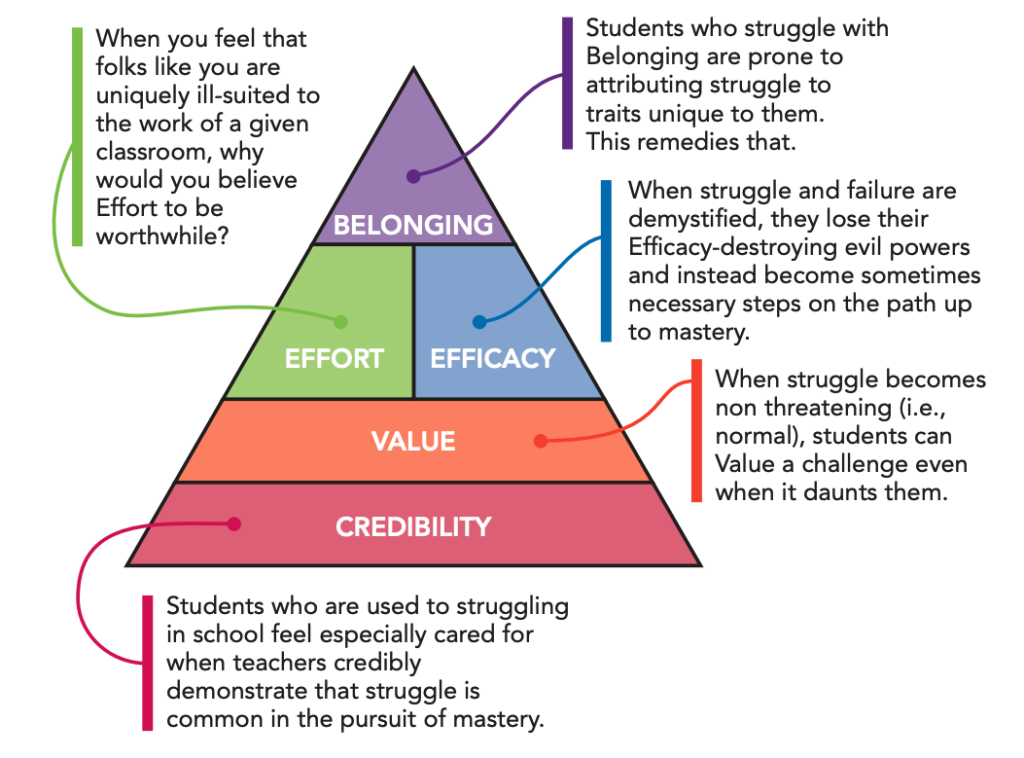

How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

While the “unpack outcomes” strategy is found in the Belonging chapter of The Will to Learn, it has an influence on other beliefs as well.

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

Some of my students struggle much more than their peers, and they are very self-conscious of this.

This hang-up reminds me of a student I taught not that long ago — let’s call her Lindsay.

Lindsay was warm and beaming during the first week of school. She was outgoing and positive; I can still remember the “Be the best at being kind” T-shirt she wore during that first week. She really was the best at being kind.

Over that first semester, however, I saw Lindsay’s affect slowly drain of its winsome energy. That bright spirit from the first week seemed to exactly track with her performance in the class: As the units came and went, her declining results on formative and summative assessments deeply disappointed her. What was worse, though, is that I could sense Lindsay was starting to believe she had no business being in this class with her peers. She was convinced her performance was uniquely bad — when she and her friends would gather when class ended, I could feel her pain each time someone asked, “How’d you do on the assessment?” She knew she’d have the worst score in the group.

It was a classic case of anti-Belonging taking root in the heart of a young person. And for months and months, I had a hard time dislodging it, despite my efforts with all the strategies in this book. It was the kind of thing I see each year in my classroom practice. Five Key Beliefs work is gardening, not button-pushing. You control only so much. Sometimes the pains you seek to mend are stubbornly resilient.

The moment of change came at the start of second semester. During an MGC attempt in the hallway (Strategy 1), I conversed with Lindsay about how she felt her first semester had gone. Her eyes went downcast instantly.

“Lindsay,” I said. “Can I ask you a different question? Do you ever compare yourself to the other students in class?”

She looked right up at me, startled.

“Yes.”

“All right. Wow — that was honesty right there, and I want to tell you that I appreciate that. That’s real stuff. Gosh, do you have courage. Thank you.”

“Okay.” Smile.

“Lindsay, what if we did this: What if the whole goal this semester was for Lindsay in three months to be someone stronger and smarter and more capable than Lindsay today? In other words, what if you and I made a pact that the only person you needed to compare yourself to for the next three months was you? What if you and I said, ‘That’s what success is this semester for Lindsay — self-improvement'?”

She nodded.

“Could we do that?”

She nodded again.

“All right — let’s do that. And throughout that whole process, is it all right if I remind you sometimes when we’re in one-on-one moments like this that you absolutely belong in this class with this group of people? Would that be all right?”

She nodded a third time.

That was all there was to the interaction, but it really made a difference. I saw a loosening in Lindsay’s affect begin that day, a slow return to the bright spirit from the first week of the school year.

During the last week of school, Lindsay’s class and I were out on a walk after our final exam was completed when Lindsay surprised us all by having her mom bring popsicles out to us on the walking trail. There she was, beaming amongst all her classmates — all of whom had struggled that year, none of whom had struggled in the exact same way.

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: You get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply