Note from Dave: A few months ago, my friend Deborah Owen of EinsteinsSecret.net approached me with an idea for a guest post on an approach to research that seemed pretty… well, non-freaked out. I immediately loved the idea of having Deborah share this approach to research with the Teaching the Core community because it's a Common Core topic we haven't focused on much. With that being said, I think we'll benefit from what Deborah has to share. So without further ado, take it away, Deborah!

You walk into class, dreading the news that you have to share with your students. Today is the day you need to introduce the research project to them, and you know you are going to be met with groans and rolling eyes. You know that after you start explaining the project, you will then be inundated by questions, some of which are legitimate, because you forgot to anticipate everything, and some of which are ridiculous, as the students try to convince you that doing a research paper is a bad idea.

There are days when you kind of – maybe – agree with them.

You do know the many reasons that doing a research paper is valuable, starting with the fact that the students must be able to identify and gather relevant, valuable information from a variety of sources (key Common Core concepts). You also know that they need to be able to develop an opinion on a topic and present their opinion in an argumentative paper. More Common Core items to check off.

So you know all this. You try to tell the students this, but they don’t buy it. The research paper is the annual pain point in your class, and it is time to change that!

A new way to do research

If you are looking for a much better and less painful way to do research – for both you and your students – it is time to learn about the Guided Inquiry model.

Yes, there are many research process models that you can use. These include the Big Six and the Research Cycle. But there is only one model that is built not on what the students should do, but on research studies observing what they actually do. That is the Guided Inquiry model.

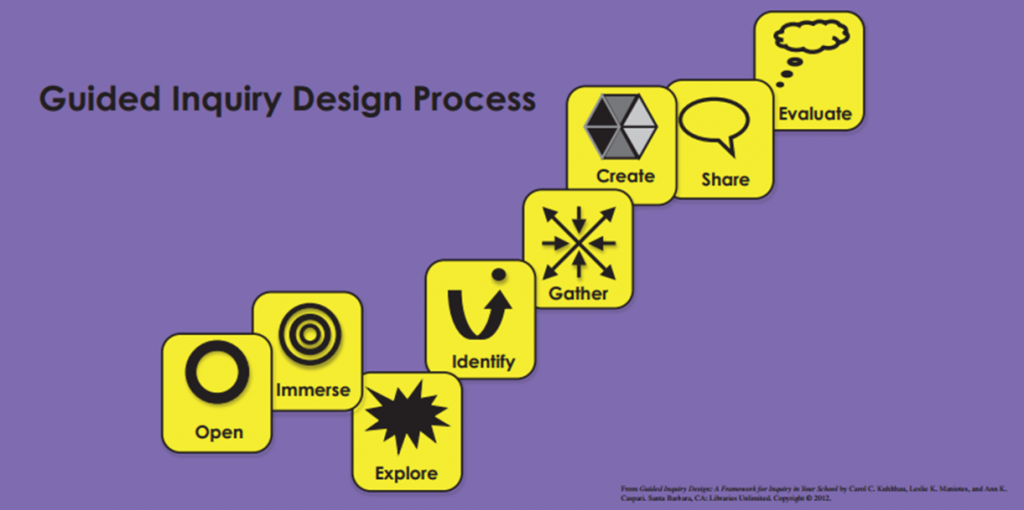

Developed by Carol Kuhlthau (professor emeritus at Rutgers Univ.), Leslie Maniotes, and Ann Caspari, the model is based on Dr. Kuhlthau’s ground-breaking studies that led first to the Information Search Process. The ISP described what Kuhlthau had observed thousands of students actually doing during the research process, as well as what they were thinking and feeling, and how all of this affected their behaviors.

Dr. Kuhlthau first described a Zone of Intervention, essentially a scaffolding system that would help the teacher to help the students with just the right intervention at just the right time. The Zone of Intervention is described as, “That area in which a student can do with advice and assistance what he or she cannot do alone or can do only with great difficulty.”

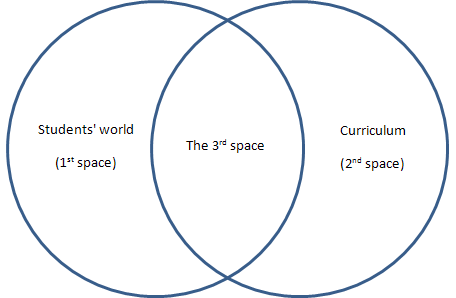

The second key ingredient of the Guided Inquiry process is that it is based on the Third Space concept (pictured below). That is, the First Space is the student’s own personal experiences outside of school; the Second Space is the curriculum that the teacher needs to teach, and the Third Space is the intersection of both of these spaces. Recognizing the Third Space honors student interests as they engage in the research.

8 Steps in Guided Inquiry

- Open – Introduce a topic to your students. You can do this with videos, non-fiction articles, objects, photographs, charts, or paintings. The purpose is to stimulate curiosity and open their minds to different ways of looking at the topic. Use evidence from the “texts” (does not have to be written words) and have your students write in their journals: “How does this connect to me?”

- Immerse – Build background knowledge; make sure the students are connecting to the content; help them discover interesting ideas. Go on a field trip or bring in a guest speaker; get involved in the local community. Have students read some more detailed information about the topic (more Common Core connections – deep reading of challenging texts). Introduce academic vocabulary about the topic. Again, have them think – and journal some more – about that Third Space.

- Explore – The students should now begin to take charge of their exploring. They should dip into information sources related to the topic, without reading deeply. They are simply trying to get a broader understanding of the topic, and begin to think about what they would like to research. They should first jot down as many questions as they can think of that might drive their research. Then as they explore, they can begin to narrow down the possibilities.

- This is where “the dip” often occurs. Carol Kuhlthau noticed that the students’ level of frustration often begins to rise at this point because they realize that there is so much information available to them, and they often become overwhelmed. This is an important time to recognize the Zone of Intervention and to be ready to help students work through their frustrations: converse with them individually; have them converse in pairs or small groups; help them narrow down their questions about the topic; etc.

- Identify – Students should stop at this point and select a question to drive their research. This is very important! Don’t let them research a “topic” (e.g., “the ethics of using performance-enhancing drugs”). They must write down a question – of extreme interest to THEM – that they plan to answer (e.g., “Under what conditions – if any – is the use of performance-enhancing drugs acceptable?”). Once they have selected their research question, based both on their initial research and on its relevance to themselves, their confidence level almost always increases.

- Gather – Students gather information that specifically answers their question. By doing the research this way, they don’t wander off on tangents! They are more focused and feel more successful. They should be cross-checking information from different resources, and they will be more willing and able to read challenging non-fiction texts because they are trying to answer a question of personal interest. This is when they actively take notes from complex texts. (Note all the Common Core skills that are addressed.)

- Create – Students reflect on what they have been learning and develop their own opinion about it. They go beyond the facts to make meaning of different ideas and synthesize those ideas into something they can call their own. Then they communicate it in an authentic, meaningful way. (Side note: Yes, students must be able to write papers. But if you can also give them opportunities to demonstrate their learning in other ways as well – Glogs on Glogster; videos; podcasts; performances of various types – then they are still synthesizing and writing, but creating other types of products.)

- Share – Students learn from each other. They have the opportunity to explain what they have learned and describe the process that brought them to their own opinion. They can tell this story using digital media and visual displays, or in performances of varying types. This step emphasizes the Common Core requirements of speaking and listening.

- Evaluate – No learning would be complete without an evaluation of both the process and the product. They should determine if they reached their learning goals, and be able to tell if they understand the new content.

No more eye-rolling and groaning!

Obviously this process is most useful when incorporated into a larger unit. It is not something that can be accomplished in a class or two, though certainly important aspects of the Guided Inquiry process can be (such as students writing down as many questions as they can think of, or journaling about how something connects to them).

As I have worked with my own students and staff members, some of the most attitude-changing aspects of Guided Inquiry have included:

- Students are able to connect the curriculum to something that matters to them, personally.

- Teachers are given a framework around which to introduce both the content curriculum, and the skills required by the Common Core.

- Students’ emotions are acknowledged and teachers know how to help them through the tough spots.

- Students’ own questions drive their research, and their research has purpose that they understand and buy into.

- Students read challenging, complex texts as a result of wanting to answer their driving question.

Don’t let your next research project lead to the same old eye-rolling and groaning! Learn how to use the Guided Inquiry model and both you and your students will be much happier!

For more information, you might want to check out these books:

- Guided Inquiry: School Libraries in the 21st Century (online paper)

- Guided Inquiry – brief explanation (Deborah’s school library website)

- Guided Inquiry Design: A Framework for Inquiry in Your School by Kuhlthau, Maniotes, Caspari

- Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century by Kuhlthau, Maniotes, Caspari

What have been the most frustrating aspects of your students’ research projects in the past? How might the Guided Inquiry model help overcome these challenges?

[hr]

Deborah Owen is a high school library teacher in Massachusetts. She is especially interested in helping students develop self-motivation, and in helping teachers and parents present self-motivating ideas to students! She loves reading, research and writing, and sharing that enthusiasm with kids. Deborah blogs at EinsteinsSecret.net, and can be found on Twitter (@DeborahCOwen) and Facebook. She has published articles in the journals Library Media Connection and Teacher-Librarian.

Mary Lou says

I love this! I will try this approach next semester!

Susan S. says

I agree with you that students should be given other ways to demonstrate their learning than writing an essay. My most recent blog: http://atfunion.org/2014/01/04/tocc-has-your-student-ever-said-i-want-to-be-an-essayist/#comment-3824

WindyD says

This is not “Common Core”. Such ideas have been around for a long time. Good teachers, like the one, above have always been able to engage the student. I know, because I’m a teacher and have used such ideas to get kids interested and excited about research. (Research-My love in life-thanks to teachers almost a half century ago).

“Common Core” is written by a few for a few to get rich from school tax money. Common Core did not formulate this idea–but attached to it. Unfortunately, for students, teaching to the tests will kill true research.

Don’t believe it?–“Research” the Common Core.

davestuartjr says

WindyD, thanks for commenting! There are definitely sources out there that corroborate your claims — but are they reliable? Are they backed by valid evidence?