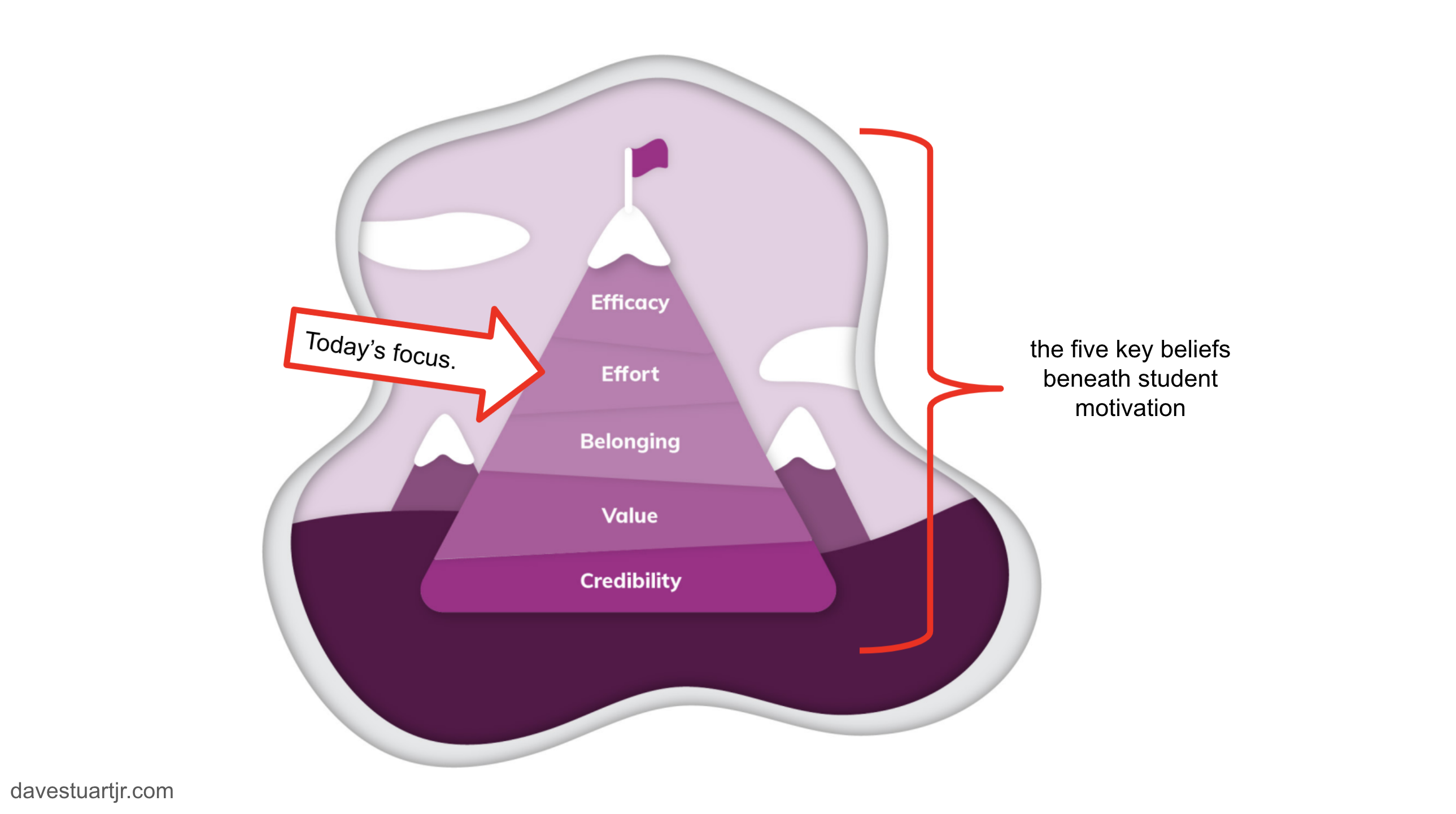

Well hey there, colleagues — how in the world are you doing? With my school year two weeks away from starting, this week finds me fortunate to learn with colleagues in Rootstown, OH; Colorado Springs, CO; and Lindon, UT. In all these places we get to play at unpacking the five key beliefs beneath student motivation, looking at things like pop-up debates as we go. It’s sure to be such a good time. Be in touch if you’d be game to think about partnering for PD in the future.

But guess what we get to talk about today? The Effort belief — whoo, this is a big one! And if you’re not caught up on the series, this is me strongly recommending that you set some time to do so. We’ve covered some ground the past few weeks:

Intro to series:

- Part 1: On the Teaching of Souls

- Part 2: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Part 3: Five Critical Qualities about the Five Key Beliefs, in Order of Actionability

Practical tactical stuff:

- Credibility Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Establishing Teacher Credibility in the First Weeks of School

- Value Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Cultivating Value in the First Weeks of School

- Effort Guide: Read below!

- Efficacy Guide: Coming next week

- Belonging Guide: Coming the following week

👉 Psst! Never miss an article again! Subscribe to my weekly newsletter and be the cool colleague forwarding sweet articles to the team.

All right — today’s focus: the Effort belief. We’ve got lots to demystify here.

We’ll do this in two parts:

- I. Important Things to Know About the Effort Belief

- II. Three Strategies for Cultivating the Effort Belief in the Classroom

I. Important Things to Know About the Effort Belief

So when I say Effort belief, what do I mean?

In the heart of a student, it sounds like: [1]

- If I work hard at this, it’ll pay off.

- I can get better at this through my effort.

- I can become more knowledgeable on this topic through working at learning more.

- I can always improve at this.

- I’ve got a beginner’s mind here — and that’s a good thing.

- I can develop my talents and abilities through hard work, good strategies, and help from others.

- I'm not “dumb in math,” I've just got some improving to do, and thanks to this class I'm learning how to improve.

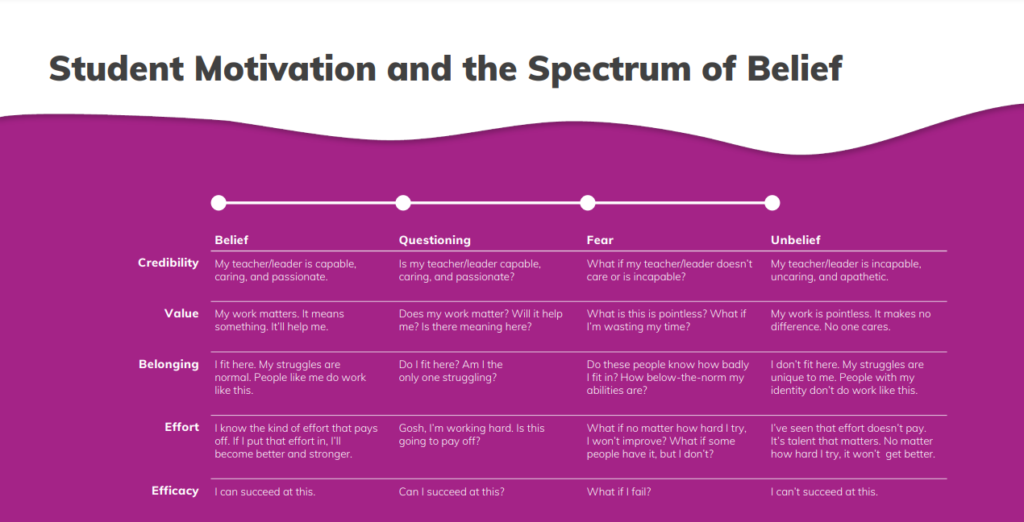

The trickiest thing about the Effort belief is that it’s growth mindset, and growth mindset is pervasively misunderstood

I always chuckle when I introduce the Effort belief to folks and some get this look on their face like, “Wait a second, that sounds familiar.” Yep, it sure does — it’s growth mindset. I guess you could say by calling it the Effort belief, I’m doing a bit of rebranding.

Now why in the world do that, Dave? Seems kind of crass.

I know, but here’s the deal: when a term in education becomes hyper-popular, it tends to get extended beyond what it means. Semantic linguists call this extension, and the first time I really observed it as a writer was during the heyday of close reading. Now a lot of times, educators get sort of cynical about things like this — “Another year, another buzzword” — and while I understand that impulse, I think it ends up robbing us of some important tools.

And that’s especially the case with growth mindset. There’s a rigorous, well-replicated body of studies and research behind this idea that when a person believes they can improve at something it has a weirdly large effect on whether or not they’ll end up improving. But I call it Effort belief because:

- I want to get beneath the widespread misunderstanding and/or cynicism around growth mindset;

- I think “mindset” is a psychologized way for talking about belief, a much older and (for me) easier to grasp term than mindset; and

- When a term like growth mindset gets buzzy, it starts getting decontextualized, and decontextualization leads to inaction ability. In other words, I want you and me to see that growth mindset is one of five key beliefs beneath student motivation, and we most productively think about it in the context of the other four.

And one quick note of mad respect here: growth mindset’s buzzwordification hasn't been despite heroic efforts by lead mindset researcher Carol Dweck. A ton of my understanding of the effort belief comes from her post-2015 efforts at correcting misunderstandings around the belief. Check out articles like this or this, and the updated version of her book (says “updated” on the top front cover).

Things that don’t work for cultivating the Effort belief

In no particular order, let’s make that above point really practical. All of these things don’t work for cultivating the Effort belief (AKA growth mindset).

Viewing it as a silver bullet. No matter how hard a person tries, they can’t instantano-magically overcome years of poor instruction or knowledge-lite curricula. Motivation isn’t the the only thing we’ve got to attend to in our classrooms — that's not the point of this series — but instead is, in my view, the best lever to start digging deeply into as professionals and experts-in-progress.

Telling kids, “Work hard! Work hard!” Exhortation to work harder isn’t the key to cultivating the Effort belief because belief is knowledge in the will not knowledge in the head. If I consciously think, “Okay, I’m going to work hard! I believe it will pay off!” that doesn’t mean I necessarily believe it. This is where beliefs get both tricky and awesome. I dive deeper into that here, here, and here.

Praising ineffective effort. A massive (and misguided) takeaway from the buzzy days of growth mindset was that you’ve got to praise effort, not intelligence. It all stemmed from the classic versions of growth mindset studies, which went something like this:

- Group A and B are both given a manageable math puzzle to complete. They all succeed.

- Group A is told, “Hey, you succeeded! You must be smart.”

- Group B is told, “Hey, you succeeded! You must have worked hard.”

- Groups A and B are then given another math puzzle, but this one is way harder. Group B does way better than Group A and persists way longer.

That’s the gist. So the takeaway for a lot of folks was, “Okay, always praise effort!”

But what critical thing happened right before the praise variables were introduced? The students succeeded. So the praise was helping students attribute success to effort rather than inherent ability. It wasn’t about motivating effort in the future — it was about attributing success in the past — to effort.

So now let’s go back to that common misapplication: praising effort regardless of outcome. When we have a student who has failed at something and the student says, “But I worked really hard at it!” and then we responded, “Well, you tried hard and that’s what counts,” we end up sending a really confusing message.

Students know that in the video games they play and the sports they participant in and the stories they watch that effort isn’t a goal — it’s a means. And when we praise ineffective effort in students, we send this message that overtime adds to school being a pretty incoherent, out-of-touch place.

Long-term, praising the process when the process doesn’t work undermines the Effort belief. So only praise the process when it works!

(We’ll talk about what to do when the process doesn’t work in a minute — see Strategy #2.)

”Students, you can do anything!” This is another one of those attempts at getting folks to try harder by “pumping them up.” The five key beliefs don’t have a thing to do with pumping up; they’re about creating conditions where student motivation is a common sensical byproduct of the environment. Sometimes I love showing my students little examples I come across of successful folks describing the work it takes to get them to the place where they are super successful. Good little discussions pop out of these kinds of things — discussions about who defines success, what myths we have as a culture, what’s a better way of saying, “You can do anything.”

”Students, shame on you for not having growth mindset! You’ve gotta have growth mindset!” I agree with Carol Dweck — this is the worst byproduct of misunderstanding growth mindset. Scolding a person for not having a growth mindset is totally nuts — it doesn’t work, and to the person it doesn’t make sense. It turns school, which should be one of the most beautiful spots in the community just based on the value of what’s on offer, into a bad place.

I have zero interest in my students even knowing what a growth mindset is. I used to be into that, but now, no. Knowing about that word doesn’t make it easier to have it — it actually makes it harder.

Assuming that beliefs are static. As I’ve said, human hearts aren’t switchboards, they’re gardens.

At peak buzz, growth mindset became something that folks either had or didn’t have. But beliefs don’t work like that, do they?

- Beliefs are dependent on context, meaning that I might think I can get better at poetry but think there’s nothing I can do, one hour later, to improve myself as weightlifter [2]. Saying, “We have growth mindset here,” is basically saying, “At all times and in all places, we all believe that we can get better at anything at all through wise effort.”

- Belief is largely unconscious. Knowledge held in the will, remember? So “I have growth mindset” just isn’t a claim that folks can make. We’re better off with something akin to the father in Mark 9 — “I believe, help my unbelief.”

- Belief exists on a spectrum. You don’t just switch ‘em on and off.

All right. I really hope that section up there helped. It’s just so important to understand those things if you’re going to optimally cultivate the Effort belief in your school and classroom.

Now let’s make it practical!

II. Three Strategies for Cultivating the Effort Belief in the Classroom

Strategy #1: The John Wooden Approach: Teach ‘em How to Tie Their Shoes

In most of the groups I lead PD with, there’s at least one person in the audience who is nerdy enough to know how John Wooden started basketball practice each season. As a famed coach of the UCLA Bruins in the 60s and 70s, you’d think he would start with something profound or ground-breaking. After all, the guy was getting top recruits from around the nation; such an elite group needed something special for the first day, right?

Well, depends on how you define special. But here’s what Wooden did: he taught them how to put on their socks and tie their shoes. In his own words:

I think it's the little things that really count. The first thing I would show our players at our first meeting was how to take a little extra time putting on their shoes and socks properly. The most important part of your equipment is your shoes and socks. You play on a hard floor. So you must have shoes that fit right. And you must not permit your socks to have wrinkles around the little toe–where you generally get blisters–or around the heels. It took just a few minutes, but I did show my players how I wanted them to do it. Hold up the sock, work it around the little toe area and the heel area so that there are no wrinkles. Smooth it out good. Then hold the sock up while you put the shoe on. And the shoe must be spread apart–not just pulled on the top laces. You tighten it up snugly by each eyelet. Then you tie it. And then you double-tie it so it won't come undone–because I don't want shoes coming untied during practice, or during the game. I don't want that to happen. I'm sure that once I started teaching that many years ago, it did cut down on blisters. It definitely helped. But that's just a little detail that coaches must take advantage of, because it's the little details that make the big things come about.

John Wooden, as told to Devin Gordon (source)

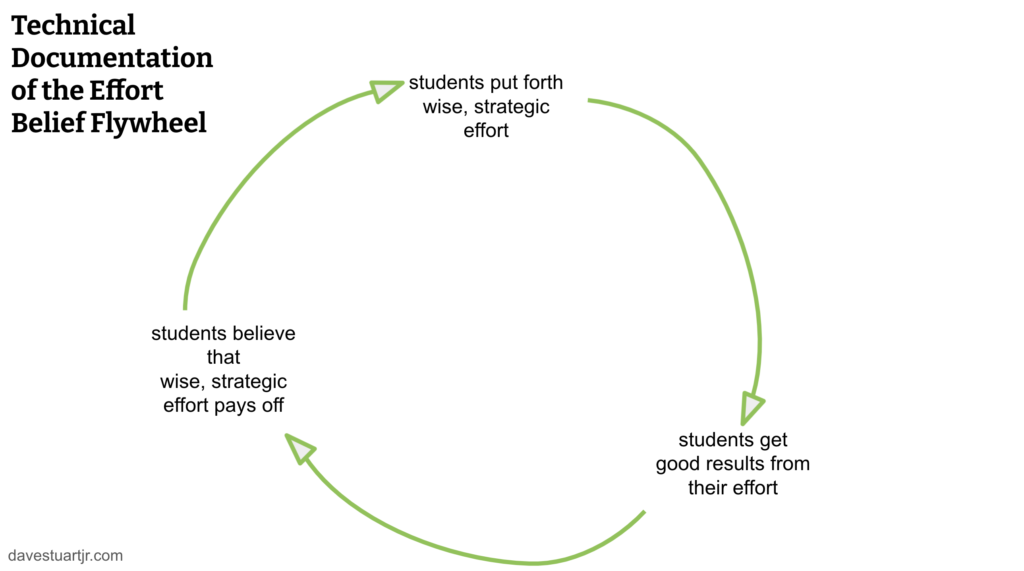

As a teacher, John Wooden understood that a huge amount of human effort is wasted every day — that efforts aimed at improvement often fall short not for lack of will, but for lack of strategy. This was a central hypothesis of his philosophy — and so he left literally no action untaught. Passing, dribbling, shooting — he aggressively structured his practices as what you and I would call lessons, making sure his elite players knew the fundamentals at a level of intimacy that most players at the time did not.

As a result, Wooden produced team after team of athletes who were peerless in their grasp of what good effort looks like. This gave them greater returns on the effort they spent in practice and in games, and these returns reinforced their (right) belief in their ability to improve through wisely applied effort.

That’s what we call a flywheel — once it’s spinning, it doesn’t stop. That’s what you and I want to do in our classrooms.

So real practically, do this:

- What are five things you’d like all of your students to be able to proficiently do by the end of the first month of school? Think specifically about learning strategies you’d like them to employ — taking notes, reviewing for quizzes, completing a written warm-up, keeping track of confusion [3].

- What would it look like, as simply and clearly as possible, to teach these to students in the first weeks of school? You’re not hijacking whole class periods — you’re using 10-15 minutes to make good effort super clear. (More on that in Strategy #3.)

- Do it! Teach those five behaviors. Even write them on an anchor chart as you introduce them so students know that you mean it when you say that doing these well does all kinds of good for all of us.

- Then, check for understanding. Look at student notes, ask how homework went, quiz students on why self-quizzing is the way to study, give warm critiques.

And if you feel like you’re kind of weak on knowing what kinds of learning efforts yield the best learning results, consider making one of these your next professional read — you will not regret it.

- How Learning Works, by Fisher, Frey, and John T. Almarode. This is a new one, haven’t read it, but it’s on my list and I like what they do

- Make It Stick, by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel. This is the OG for me. It was my first introduction to the concepts of retrieval practice, spaced practiced, and interleaved practice.

- Uncommon Sense Teaching: Practical Insights in Brain Science to Help Students Learn, by Barbara Oakley. Barbara is the best — so readable, so interesting.

- A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra), by Barbara Oakley. This is the first time I read Barbara Oakley. And if you're thinking, “Wait Dave, aren't you a humanities teacher?” then you're not understanding yet how good Barbara Oakley is.

- Basically anything by Cal Newport, but for this recommendations list let's go with How to Become a Straight-A Student: The Unconventional Strategies Real College Students Use to Score High While Studying Less — he’s hardcore; really he's writing for folks like you and me on how to live a deeper life and succeed as a side benefit. Cal's a 3D chess in a world of checkers kind of guy. I really appreciate him.

- Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning, by Pooja Agarwal and Patrice Bain. Powerhouses in the science of learning world.

- What If Everything You Knew About Education Was Wrong? and Making Kids Cleverer: A manifesto for closing the advantage gap, by David Didau. Didau is decidedly British — tongue in cheek, sharp as a tack, deeply thoughtful, unafraid to ruffle feathers. He writes manifestos, not books. I love his energy, even though I often disagree with him. He makes me think.

- Why Don't Students Like School?: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom, by Daniel Willingham. I owe no one a greater debt for my understanding of cognitive science than Daniel Willingham. He is a legend — the Godfather of making cog sci accessible to teachers. If you've not got the money for any of these books, check out his articles for AFT, all linked to here.

Strategy #2: Unpacking Failed Effort: Make the Most of When Things Don’t Work

So here’s a common enough scenario:

- Mr. Stuart, I studied for like ten hours this week! I’m going to crush this test!

- (Sixty minutes later) Leaves room silently, long-faced.

- (Next morning, in tears) Mr. Stuart, I don’t understand! I worked so hard, and I failed!

You already know what NOT to do in this situation — don’t give consolation praise! No, “Well, at least you tried; be proud of that.” Heck no — you’re a teacher! You’ve got to un-obscure the success path.

So what you do is say:

- Oh my goodness, Stephan, I saw your score and was so bummed. Listen, I don’t want you studying ten hours for anything in my class; I want to help you put in less effort and get way better results from it. So can you and I meet up for just fifteen minutes today during lunch or after school? I think we could get really far in that short amount of time.

Then when the student comes in, your have two jobs:

- Figure out what in the heck happened during those ten hours. You want as much clarity on the student’s current learning strategy as possible.

- What I often find here is that students are using stuff that feels like studying but isn’t (e.g., re-reading notes, re-reading texts, watching related YouTube videos, last-minute marathon jam-cram sessions).

- Give the student 1-3 “try this instead” action steps. Here, you’re picking the stuff that’s most likely to get the biggest improvement next time.

- Here, the solution is almost always some variation on the basics from learning science: spaced practice (v. cramming), self-quizzing (v. re-reading notes or text), elaboration (v. mindlessly consuming additional content).

These are outside the purview of this article, but if any of the last 100 words is unknown to you, you’ll get a lot from taking a look at 1-2 of the books I recommended in the previous section.

(Here’s an article I wrote a while back about a specific student that I helped through the process above; in this student’s case, we found out in our time together that she was studying effectively but was managing text anxiety ineffectively. So, I gave her some things to try for that and it worked so well that she wrote to me about it several years later.)

Strategy #3: Show AND Tell: Use Examples to Make the Unclear Clear

Early on when I was interested in becoming a writer, I remember seeing this same little piece of advice about a million times: show, don’t tell. It’s good advice for writing, but with a tweak, it’s some of the best advice about teaching you can get.

If you want students to put forth wise effort, show them specific examples of what it does and doesn’t look like and tell them as clearly as you can why the specific examples do and don’t work.

- Teaching a lab report? Show students an example of a good introduction, a good presentation of results, a good conclusion. Point out the top 1-3 characteristics that make these elements of a lab report strong. Then show an example of what these elements look like when it’s done poorly.

- Teaching purposeful annotation? Put the text students are reading right up on the document camera and walk them through how you think about annotating towards a purpose. (This article I wrote is super-detailed about this process.) Want to make it clearer? Share an example or two of non-purposeful annotation that you’ve seen students use (e.g., underlining every sentence in a paragraph).

- Want article of the week written responses to improve? Put 1-2 anonymized examples on the screen from previous weeks and 1-2 anonymized non-examples. Don’t feel comfortable making anonymized examples from your students’ work? Make them yourself — compared to spending 10-15 minutes making a pretty worksheet, spending 10-15 minutes creating an exemplar is about a million percent more likely to improve student outcomes in your room.

- Teaching students to do pushups in Phys Ed? Have a willing volunteer show some pushups with back straight and pushups with back curved or booty in the air. Explain to students what’s happening in the body during both the example and the non-examples; ask them to remind you what the goal of a pushup is and then to tell you which pushup example is most likely to get to that goal.

- Teaching pop-up debate? Before the debate, give students a template or two to play with — I use Paraphrase Plus. Specifically, pick templates that solve problems you’ve noticed about student speaking lately (e.g., when my students silo speak, I teach paraphrasing, see Chapter 7 of T6T). Then during the debate when a student successfully employs a template, quickly interrupt and say, “Do you see what Jami did there? Man, that was cool. That’s paraphrasing. Notice how she modified the template I showed you all before the debate? That was playful, smart. I love it. Nice work, Jami.” And don’t be afraid to pop-up and offer your own non-example. Afterward, say to students, “All right, so what did I intentionally not do during the speech I just made?

You get the idea, eh? It’s really just Teaching 101 — except that for too many of us, Teaching 101 ends up being this mystifying thing where we turn teaching into something way more complicated than it needs to be.

Now look: even once you’ve done Show AND Tell, your students will still need to exert effort to get their own learning work done. You’re not doing the work of learning for them — you’re just making the work super clear. You’re leaving nothing to chance — no assumicide in your room. Some of your students will already know what good effort looks like, but it’s still okay to have them attend to these brief little Show AND Tells.

I mean, after all, I’m pretty sure all of John Wooden’s athletes knew how to tie their shoes.

Tune in next time

That about does it for the Effort belief. If you can internalize Part I of this article and put into practice the three strategies in Part II, watch out my friend! You’re going to be building something pretty special in that classroom of yours.

Best to you,

DSJR

P.S. Next time, we’ll look at the Efficacy belief.

Footnotes:

- As we discussed in this article, beliefs are knowledge held in the will — meaning they are not necessarily things that we think about or articulate. So when I say, “Sounds like,” I'm not speaking literally.

- Easy trap to fall into when you are a professional bodybuilder such as myself. 🤷♂️

- I’m going to do my best to create articles and videos on how I do each of these this school year. Be sure to subscribe to the newsletter for the articles and the YouTube channel for the videos.

Jordan says

Hi Dave! Thanks for your post. I’m a preservice teacher thinking a lot about student (and my own) motivation. You mentioned that you don’t really care if students know about growth mindset and stopped teaching about it explicitly. I’m wondering if you could say more about why you made this switch. I have this impulse to share everything I learn about in my teacher ed program with my students as a form of transparency and also a kind of “if it’s good for me it should be good for them” thing. What are your thoughts on the balance between what students need to know and don’t need to know about theory or philosophy behind our teaching practices? Thanks so much! I’ll be checking out further posts and also practicing how to tie my shoes.

Dave Stuart Jr. (@davestuartjr) says

Jordan, it’s great to hear from you. I decided to respond in a video — here it is 🙂 https://www.loom.com/share/38ec51d6cd9c4fba91dd30931ca5dc95