Hello, colleague — what in the world do you think we have in store for us today? Who can know, right? But here’s one part of today that I know we’ve got coming — a big ol’ practical treatise on how we can all make the Efficacy belief a bit more commonplace in every one of our classrooms.

Before we get into it, shout out time! I was so grateful to be with colleagues at Monument Academy and Oak Canyon Junior High School last week. I can’t even tell you how fun it is to get a bunch of earnest, amicable educators in a room and cut ‘em loose on learning about the fundamentals of student motivation.

This week had me heading to Kalispell, MT for the great honor of keynoting at the annual conference of the Northwest Montana Reading Council. The only problem I ever find with heading to Montana is that I have to look at a LOT of pictures of my wife and children to motivate me to get on the plane to come home. It is just something else out there, especially in that Flathead Valley.

(Want to look in to booking me for your school or event? Learn more here, then reach out here. I’m particularly interested in partnering with schools on year-long PD efforts, and I’ve got some pretty cool case studies running this year for doing that with aplomb. Just reach out, and we’ll chat more.)

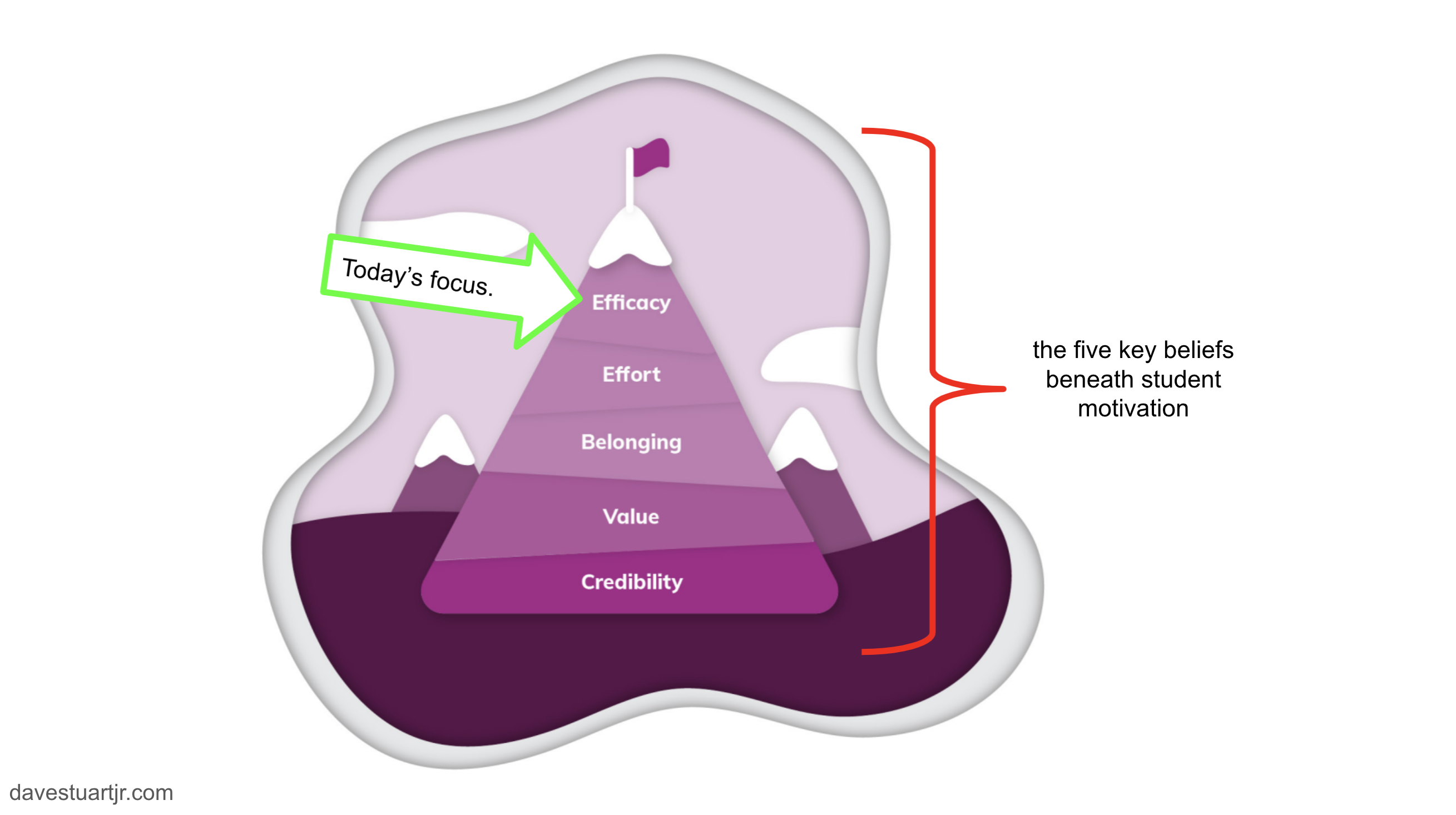

So before we get in to learning about our best friend the Efficacy belief, if you’re not caught up on the series we’ve been doing, this is me strongly recommending that you set some time to do so. I don’t think you’ll be wasting a single minute. Here’s what we’ve covered this summer:

Intro to series:

- Part 1: On the Teaching of Souls

- Part 2: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Part 3: Five Critical Qualities about the Five Key Beliefs, in Order of Actionability

Practical tactical stuff:

- Credibility Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Establishing Teacher Credibility in the First Weeks of School

- Value Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Cultivating Value in the First Weeks of School

- Effort Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Cultivating Value in the First Weeks of School

- Efficacy Guide: Below!

- Belonging Guide: Coming next week in epic concluding fashion.

👉 And hey! Want to never miss an article again! Subscribe to my weekly newsletter with your very best email address and become the cool colleague who forwards sweet articles to the team. I send out a new post every Tuesday and Thursday. And that’s all I send.

All right — today’s focus: the Efficacy belief. It’s time to get all Albert Bandura on you.

We’ll do this in two parts:

- I. Important Things to Know about the Efficacy Belief

- II. Three Strategies for Cultivating the Efficacy Belief in the Classroom

I. Important Things to Know about the Efficacy Belief

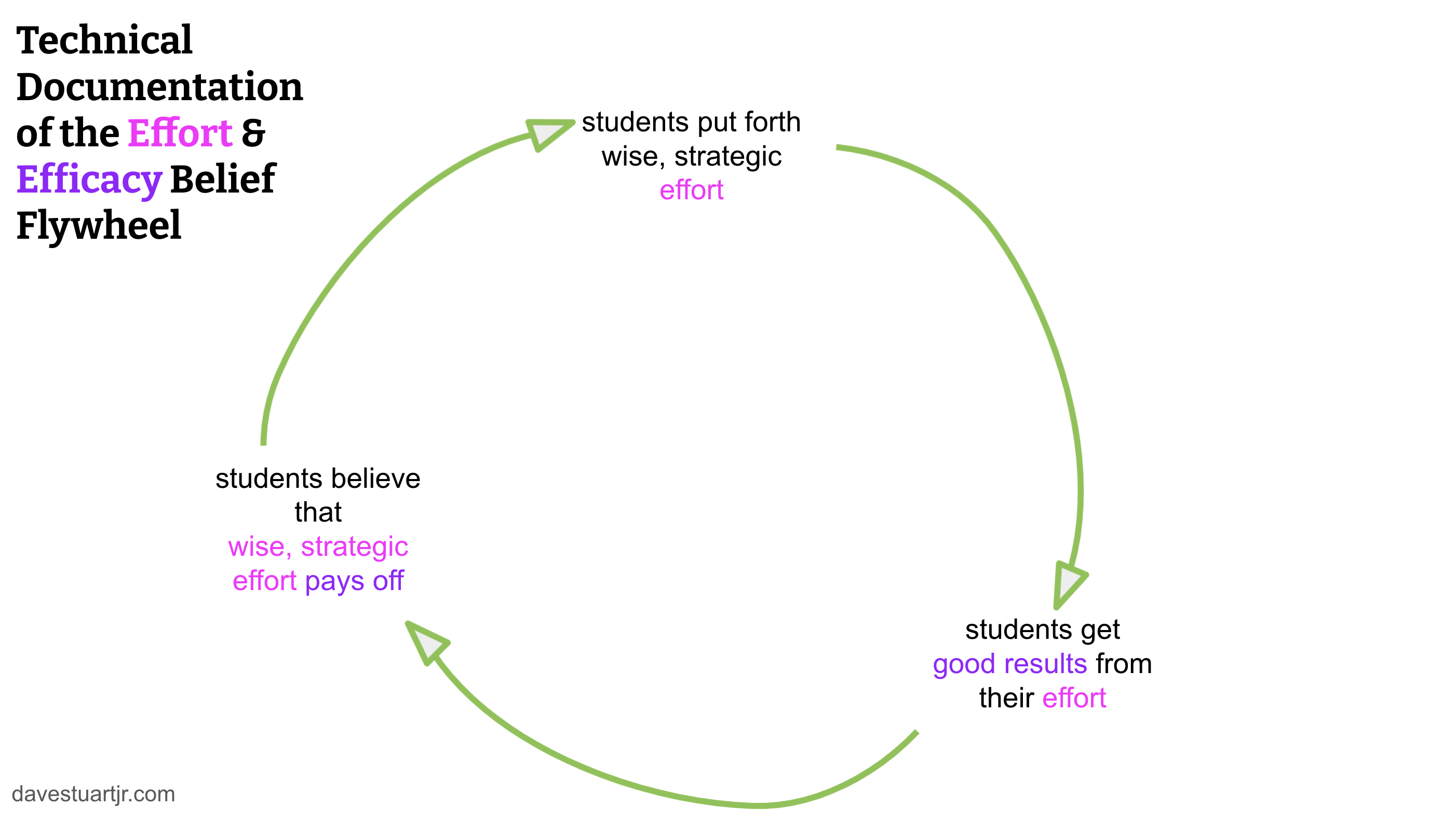

Sometimes I get to thinking about the Efficacy and Effort beliefs like a pair of sneakers — they work closely together. As we teach students to apply wise effort to tasks and teach them to wisely define success on those tasks, our students are more likely to put forth wise effort and, therefore, succeed at those tasks (provided success is defined wisely — more on that below).

It’s a flywheel — and we like flywheels, you and I, because once flywheels get spinning, they continue to spin on their own momentum.

So if you missed last week’s article on Effort, check it out here. But now, let’s get deeper into Efficacy.

In the heart of a student, Efficacy sounds like this:

- I can succeed at this.

- I’ve got what it takes to achieve my goal.

- This assignment is doable.

- Success on this project is possible for me.

- I know what to do to get where I want to be, and I know I can do it.

Here are a few things to keep in mind when trying to cultivate Efficacy:

No one likes working at something that they suspect is doomed to fail.

Think about it:

- When’s the last time you worked hard at writing an essay that you were certain had no chance at being good?

- When’s the last time you did a physical exercise that you thought for sure was going to be wasted pain and effort?

- When’s the last time you picked up a new learning project and got derailed by seeing someone that seemed hopelessly further along than you?

Never, right? It’s just a deeply demotivating thing to know you’ll fail at something. So when a student says something to me like, “I can’t do this,” if I sense that they sincerely believe this, I want my first response to be compassion. Demotivation is experienced as pain. Not a single human being likes the feeling of being demotivated — not in school, not at home, not when they look in the mirror.

From a position of compassion, we can start digging into root causes of anti-Efficacy.

Not everyone can succeed at everything in the same way.

There’s this really important tension to be aware of as a teacher:

- On the one hand, every student deserves the blessing of high expectation learning experiences, regardless of background.

- On the other hand, not every student is equally prepared to realized a high expectation in a given time frame.

If you take my daughter Hadassah, a capable swimmer, and put her in a pool for a year with an Olympic swimming coach, expecting her to break a world record is absurd. Given where Haddie is as a swimmer, the path to world class mastery is a lot longer than a year — no matter the teacher, no matter the motivation.

But if you do the same thing with, say, Katie Ledecky — Olympic coach, one year of practice — then expecting anything less than a world record is absurd.

Our classrooms are miniaturized, hyper-complicated versions of this silly scenario. In a skill area like, say, pop-up debate, every one of my students enters the year at a different level of preparedness. The range is wide — from so-anxious-to-speak-publicly-that-I’ve-never-done-it-in-class to aggressively extroverted, from deeply logical to stubbornly silly, from conflict-avoidant to clash-seeking.

The same range is there for all the other things I ask my students to do: write, read, study, learn, persist. And the same is there for yours, whether you’re teaching computer science or food and nutrition.

This is why we’ve got to define success with our students early and often. (See Strategy #1 below.)

It’s not built through hype — it’s built through proof.

The first time someone said to me, “Dave, you could be a motivational speaker guy,” I got a bad taste in my mouth because all I could picture was some cheesy poster with puppies and unicorns, emblazoned with something empty like “IF YOU BELIEVE IT, YOU CAN ACHIEVE IT!”

I’m all about human agency, but I’m not about mindlessness. I don’t want to try to get my students to believe they can do something based on some words that I say; I want them to believe they can do something based on similar things they’ve done like it in the past.

This is why the best way to build Efficacy — bar none — is succeeding. Yep — if you succeed, then you’ll believe you can succeed again, and if you believe you can succeed, you’re more likely to succeed because you’ll bring more motivation to the task.

II. Three Strategies for Cultivating the Efficacy Belief in the Classroom

Brass tacks time, eh? Let’s take a look at three ways to get started building Efficacy in your classroom.

Strategy #1: Define success, early and often.

Hoo boy, you know what? I love me some definitions. There’s nothing as lovely as having a conversation in which everyone there has a clear understanding of the words being used by everyone there. And that state of clear understanding? Super duper impossible without clear, shared definitions.

I used to be big on success with my students, and to me, success used to mean the same thing as big. I even had this big, homemade decal in the back of my first classroom that said, “Dream Big.”

But eventually, the flashy version of success lost all its luster. I was a workaholic. I quit my teaching job. I started a family. I found other areas of life that I yearned deeply to know and experience — areas that weren’t contained within the four walls of a classroom.

So when I came back to teaching, I had some defining to do. What’s an English or a history class for? What’s school for? Why do folks of all kinds send their children of all kinds to school for thousands of hours a year? What sacred trust is beneath the investments of time, energy, and resources that comprise an education?

That’s what eventually landed me on LTF: long-term flourishing. Every class we teach in a school aims to contribute toward a young person’s ability to flourish long term. I came to think of success for my students not as something you size up — big or small really didn’t come into it anymore for me — but instead was something we can each pursue through inner and outer work. This kind of success — the PERMA kind — was abundant, not scarce. My students and I were people who find themselves situated within a game that doesn’t end.

Wow, Dave… that’s purrrrty. But what’s it mean for classroom practice?

It means I want to teach the living daylights out of whatever I’m tasked with teaching. I want my students to define success as mastering as much of the course material as possible — be it the themes of Fahrenheit 451 (haha) or patterns of continuity and change in the early modern era. Why? Because the pursuit of such mastery is valuable in and of itself — all of the things that we learn in school can enlarge us — and has as its byproducts strengths of character like resilience, purpose, gratitude, and charity.

So to do that — to create a classroom culture in which success is the pursuit of mastery — here are some things that I try:

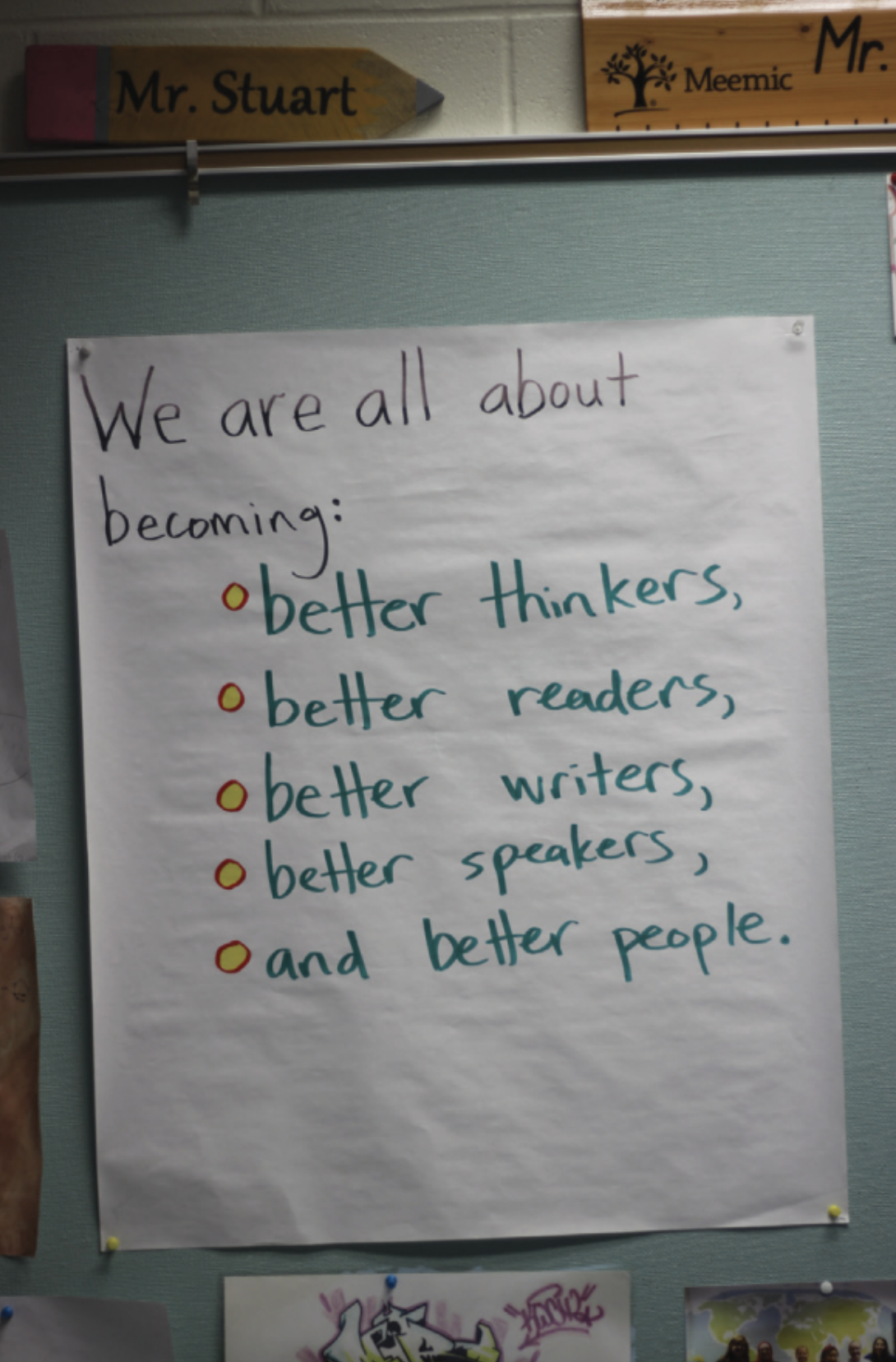

Everest poster. Up at the front of my room is the one sentence encapsulation of the peak we’re aiming for in our course-long journey together. I reference it periodically when I’m teaching, saying, “Remember: this is why we’re doing this.”

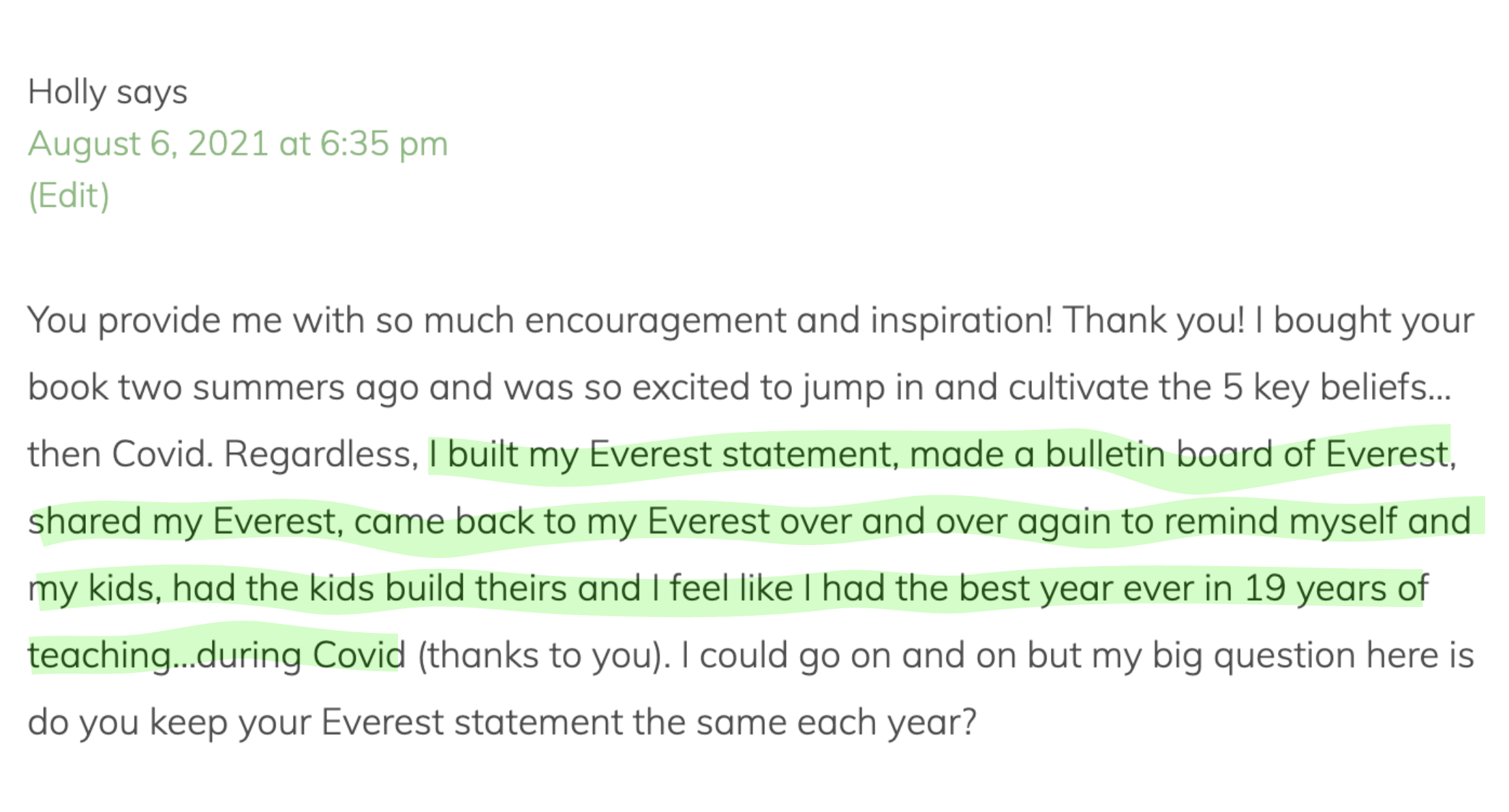

Recently, I heard from one of our colleagues that has students create Everest sentences for their school years. I like that — reminds me of the goal-setting exercise we’ll get to in Strategy #2. Check it out:

The point with Everest is to have a clear, regularly articulated picture of what it is that we’re heading toward. Pretend that success in your class actually is a weather-shrouded peak — now you be the weather-clearing binoculars.

First day of school index cards. (Not your first day? No worries — you could do this any day as a warm-up exercise.) For this one, I like to ask my students to tell me about the people they hope they’ll be someday. It’s a way of getting them to think about the vision they have for their lives and the work they can do today to get there. I explain the strategy in-depth in the second chapter of These 6 Things and in this blog post.

Intentionally repeating shorthands for what you’re after. A commonality in strong cultures is short catchphrases that come to mean more than they seem like they do. I wrote about this idea in this post, which was a meditation on this book by Dan Coyle. One of the mantras in my classroom is, “What are we after, students? Mastering the material.” Master the material — it’s got alliteration so it has to be true.

But, Dave — shouldn’t we be having students define their own success?

Yes, that’s a good idea, too. On to Strategy #2!

Strategy #2: Teach goal-setting with WOOP.

WOOP is a goal-setting process that’s been heavily vetted in experimental studies. Folks who engage in WOOP are way more likely to engage in goal-striving behaviors than folks who do non-WOOP goal-setting.

It stands for:

- Wish (feel free to change this — I like Goal; be careful if you pick Prize)

- Outcome

- Obstacle

- Plan

Wish: This is the goal. Here it’s nice to have something specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-sensitive. (Shoot, I wish there was an acronym for that.)

Examples from my ninth grade students:

- I want to have a 3.0 GPA or higher after this semester.

- I want to learn three songs on the piano by January.

- I want to stand up before being called on during the next three pop-up debates.

Typically when I lead WOOP in my class, I set some guidelines regarding content (outside of school, in school) and timeline (this week, this month, this semester, this year).

Outcome: Here you visualize what success at the Wish would be like. What would you feel? What would you do upon realizing you’d succeeded? When leading students through this, do all you can in your guidance to get them to create a vivid mental picture. What we’re about to do is some mental contrasting — and that’s hard to do without a picture.

Obstacle: Now you ask students to switch to visualize the most likely obstacle within their control that could get in the way of them realizing their goal. Things my students often answer here:

- Play video games instead of study

- Chat with my friends when I need to focus

- Waste the hour between when school gets out and my siblings get home

Plan: With the mental contrasting bit done, now it’s time for an implementation intention. Implementation intentions are simple If-Then plans regarding goal completion. Some examples from my students:

- If I want to play video games after school, I’ll complete my Spanish vocabulary flash card deck three times before plugging in the machine.

- When I finish with dinner, I’ll give my phone to my parents and ask them not to give it back to me until I can show them a fresh page of writing in my writer’s notebook.

- When my alarm wakes me in the morning and I want to hit the snooze button, I’ll do ten push-ups before hitting the button.

(The studies that undergird the efficacy of implementation intentions are neat to read about. In this one, researchers called voters and asked three questions: What time will you vote? Where will you be coming from? What will you be doing immediately prior to voting? Folks who received these questions were 4.1 percentage points more likely to hit the polls on the big day.)

What’s the big WOOP?

(😂)

WOOP is cool because it takes the classic classroom goal-setting exercise and adds two evidenced-based tools from the research: mental contrasting and implementation intentions.

The reason this helps is because it increases the likelihood that students will experience success at work of their choosing, and this success will cultivate a stronger, evidence-based belief in their efficacy.

Couple final tips for WOOPing

When you first do it, think through how you’ll lead it. I try to create a relaxed, energizing vibe. This video example is a little silly and it’s aimed at teachers, but you get a bit of the gist of my approach.

When you lead your students through WOOP, consider doing it yourself, too. The benefit here is that as the goal-striving period is underway, you can periodically share with your students your own winding paths to success. This normalizes struggle in the process — super important for the Efficacy and Effort beliefs.

Periodically check-in with your students on their WOOPs. Let’s say you lead students in setting a one-month goal regarding school. Each Monday, add a question to your warm-up asking students how they are progressing. This is a great Think-Pair-Share or Conversation Challenge activity. (Here’s an older classroom example in video.)

Strategy #3: Engineer success on something hard, as soon as you can (but not sooner).

As we’ve said, the best way to build Efficacy is by actually succeeding — particularly at something hard and valuable. There’s just something that changes in us when we’re on the other side of a thing we didn’t think we could do but discovered that we wanted to do.

Consider my mom. A non-runner until mid-life, she picks up the habit and works her way to a marathon. After the marathon, she’s got the Efficacy belief around running in spades. She may not choose to run one again, but she knows: I could. Because she went through the process and came out the other side.

In the classroom, I think of my students, many of them anxious about public speaking, who end up participating in pop-up debates all throughout the school year. Here they didn’t have as much agency as my mom — one of the few rules of pop-up debate is that everyone speaks at least one time — but there’s a lot more than you might think. My pop-up debates have no rubrics, no grades, no intimidating consequence for non-participation. It’s not me who pushes that chair out and stands up — it’s each of my students. It’s not me who makes the words come from within them — it’s them.

(Few things I facilitate in my room are as powerful for Efficacy as this. I write about the process at length in this article and in the Speaking/Listening chapter of These 6 Things.)

Slow and steady

All right — that’s a ton! And this article is past due. I hope it helps as you seek to cultivate the Efficacy belief in your room this fall.

Leave a Reply