We're into it now, colleague. If you've no idea what I'm talking about, take a look at these earlier articles in the series:

- Part 1: On the Teaching of Souls

- Addendum: But What About SEL?

- Part 2: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Addendum: Not a Switchboard, but a Garden

Or: check out this brief explainer video:

On with it.

Before we get into practical-tactical bits about each of the five key beliefs beneath student motivation, we need to rightly conceive of what the beliefs are like. As I go through this list, I'll work from broad/philosophical to narrow/research-based. In my classroom practice, all five of these qualities guide my belief-cultivation efforts.

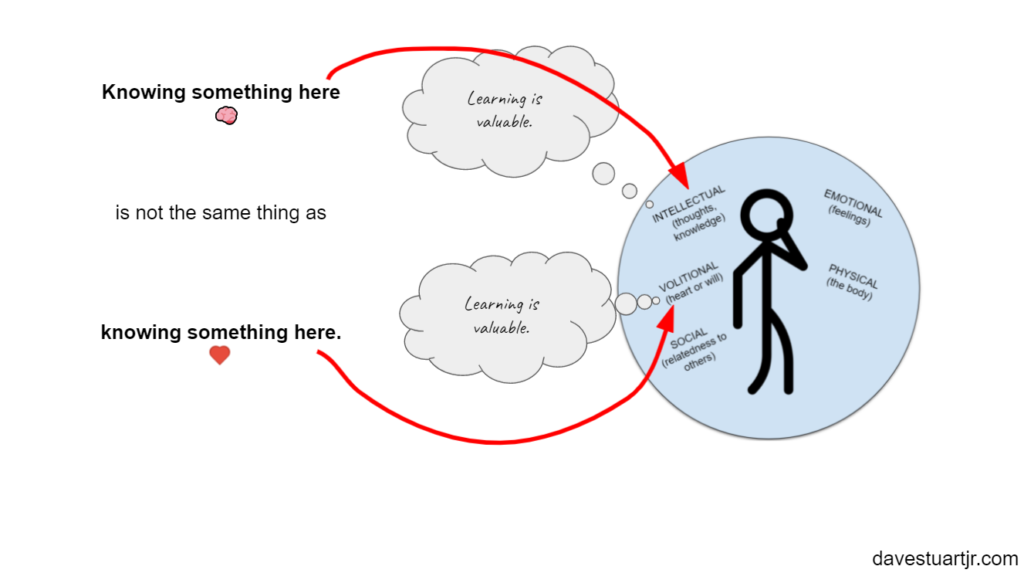

1. Beliefs are knowledge held in the will.

So, one more warning: this is going to seem super impractical. But for whatever reason, it's just kind of rocked my world and helped me understand myself and others so much better.

If I tell you what I believe, you should listen to me and factor it in to your understanding of me. But to really know what I believe, you should look at my actions because belief drives behavior. It's not the talk, it's the walk.

So for example, if I tell you that I believe all students are worth respecting at all times, but then after a hard day I speak disdainfully about a student, you should:

- Know that I do think all students are worth respecting at all times, but that

- I don't believe that is the case when certain conditions are present (e.g., a bad day, a student cussing me out, etc.).

And of course, in this example you should continue to love and value me because all I've demonstrated to you is that I'm a work-in-progress. 🙂 My beliefs are still forming.

Let's do one more example.

Why do people sit in chairs?

I know something you believe in, colleague — you believe in chairs. This is a belief that unites us all.

- We sit in them all the time.

- We trust them — even ones we've never sat in.

- Our friends all sit in them.

Super mundane, right? Exactly. That's what belief is like — it's mundane. It's the stuff you don't even think about — you just… know it, and you act on it, and you don't even think twice to act on it again and again and again and again.

It's knowledge you hold in your will. That's what we're after in cultivating the five key beliefs in our students. We want Credibility and Value and Belonging and Effort and Efficacy to be nonchalant assumptions.

👉To put it briefly:

- Belief is knowledge held in the will. It's an effortless confidence in a thing. It's a certainty, a trust. It's a readiness to act as if something were true (that's how late USC philosopher Dallas Willard explained it). It's largely invisible — not just to others, but also to us. Through our beliefs, we see and interpret the world.

💡Why it's important to know this in a classroom:

- If you think a belief is something you can just get a student to articulate back to you, you'll be really confused when student actions don't align with what they've said. For example, early in my research I remember teaching students about growth mindset, to the point where virtually all of them “had” a growth mindset according to a questionnaire we took in class. There was just one problem: my students were still afraid of failure, still acted helpless when they got stuck, still were quick to quit when things got hard. They had what Carol Dweck has since called “false growth mindset.”

🛠Try this:

- Think of belief work as the cultivation of a garden rather than the operation of a switchboard.

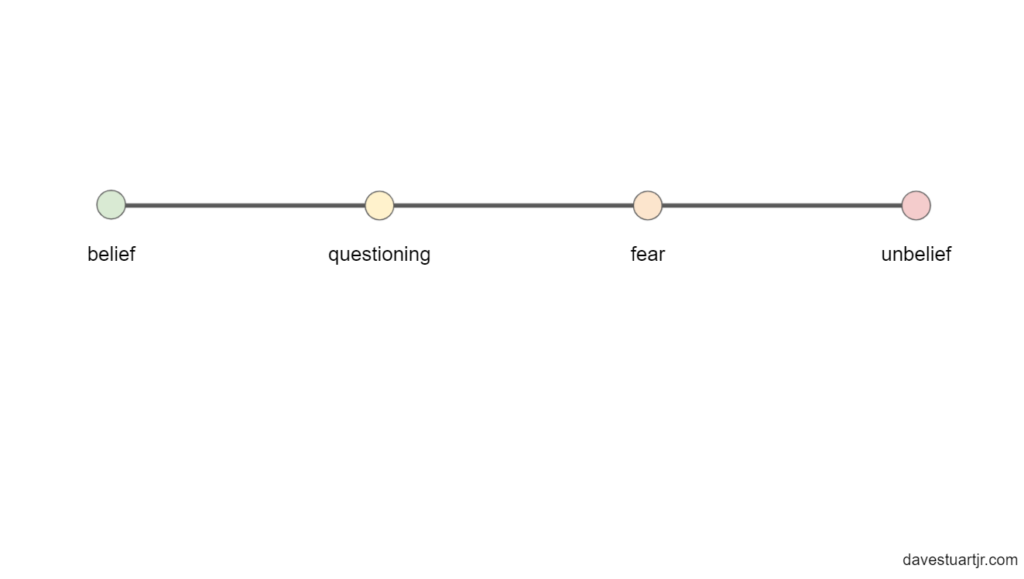

2. The five key beliefs exist on a spectrum.

All right — let's go back to chairs.

Let's imagine that I did a bad experiment on you, and for each of the next seven days I sabotaged three or four chairs that I knew you were going to sit on, and each time you sat in one of my sabotaged chairs, it failed spectacularly. By the end of the week, you've had two dozen chairs collapse beneath you; you've been humiliated; you've got a sore rear.

Following this experiment, would you think twice about sitting in chairs?

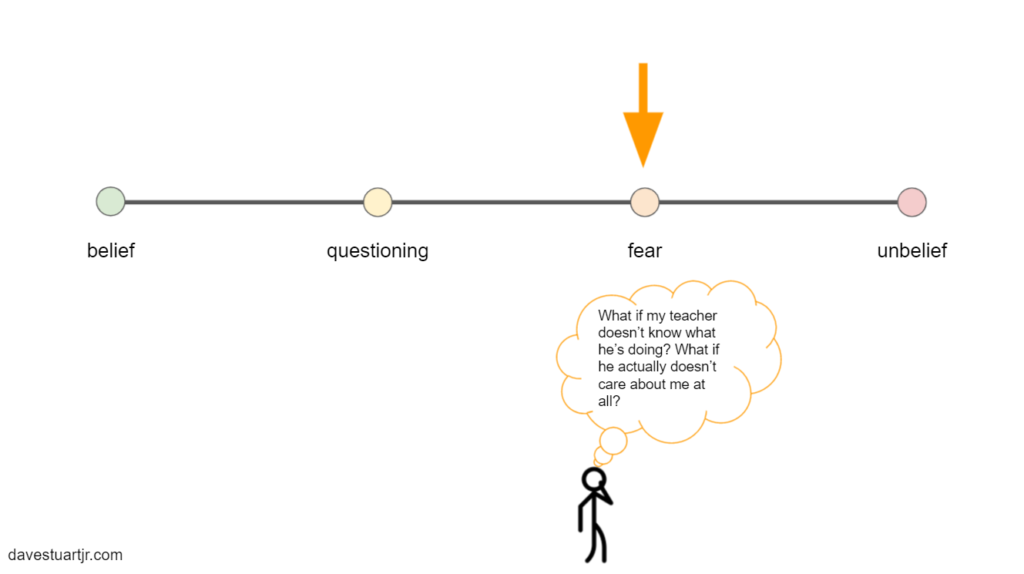

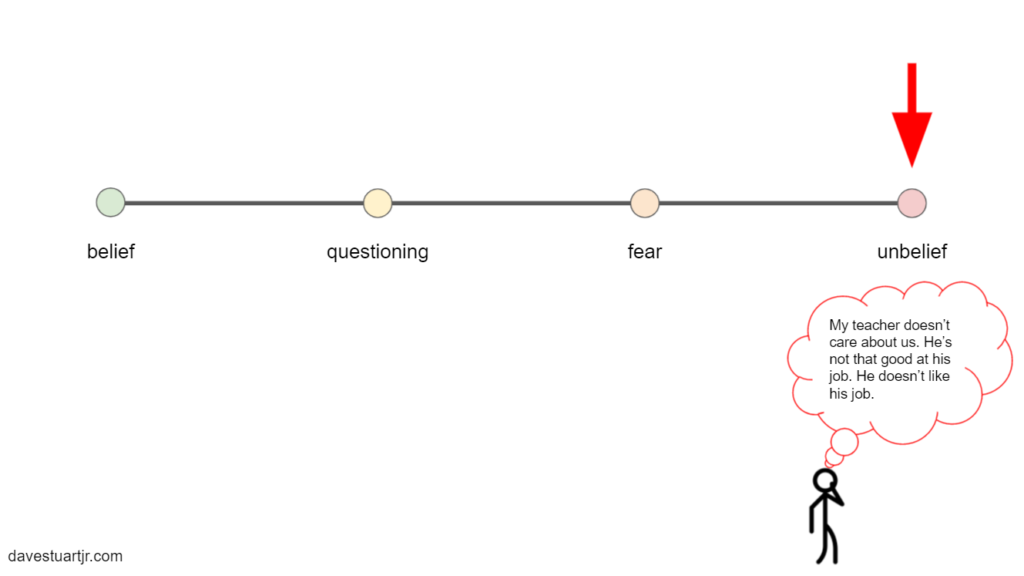

Absolutely you would. Because I would have moved your belief in chairs into the realm of questioning and fear.

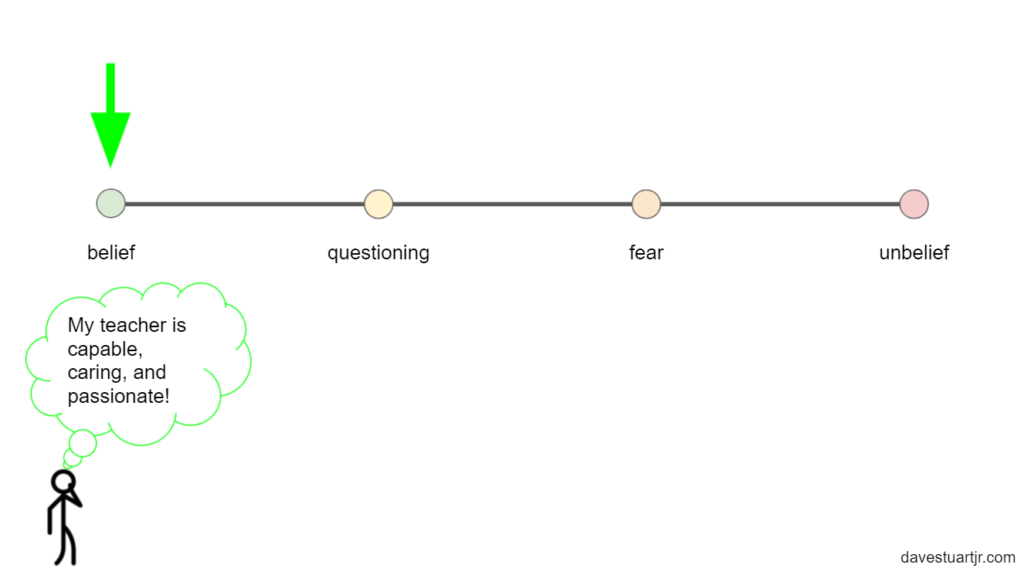

Now, let's consider a student in our classroom — say, Johnny Johnson.

First week of school, I'm super nice to him, super passionate about where we're going as learners this year, learn his name real quick, maybe even make a quick positive phone call home.

That's probably plenty of signal for Johnny to believe that I'm a good teacher. He probably thinks, “Mr. Stuart's got what it takes to help me learn this year.”

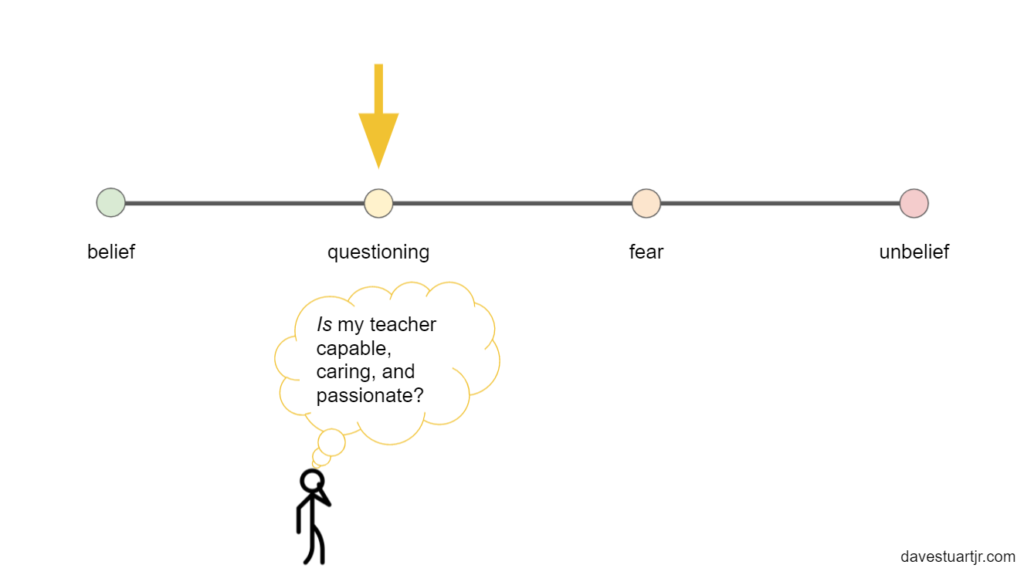

But then in October I snip at one of Johnny's friends for interrupting me. I take three weeks to give feedback on a set of student essays. My warm-up isn't posted before class starts a few days in a row.

(And by the way — if you're starting to feel bad about yourself, take heart. All of these examples are picked from my own career. I'll get to some good news in a minute. But first, the pit must deepen.)

In November, things don't get better. I assign his class an essay that feels pretty last minute, muttering something like, “Well, we just have to get it done by Friday. Department deadline. Do your best.” It ends up being a confusing assignment, and when Johnny and over half of the rest of the class all raise their hands at the same time, I quip, “Listen — just get started on your introduction, and I'll be around to help as many as I can.”

Unfortunately, the bell rings before I get to Johnny.

When he finally gets the essay back from me a few weeks later, he sees that he's gotten an A. The thing is, he doesn't understand why. He's not even sure I read it.

Things don't improve.

By January, Johnny's developed a good grade in the class, but he's not really proud of it. Writing is a grind — you just put things on paper and then hope the grade turns out all right. Because after all, that's what the class is — it's a grade, something to get through. Even Mr. Stuart basically tells him that.

For the first few minutes of each class period, there's nothing for Johnny and his peers to do. They talk, goof off, check their phones — Mr. Stuart, meanwhile, says he's “taking attendance.” When he's finally ready, Stuart has to yell over the class to quiet down. While he's explaining the day's agenda, Johnny heckles him a few times, and Mr. Stuart laughs.

Johnny has a fine relationship with Mr. Stuart — I mean, c'mon, Mr. Stuart's a cool guy. 😉

He's just not a very good teacher, that's all.

Wow Dave, that was super depressing!

Haha, I know right! Dang — got myself sad there.

So the good news is that the spectrum can go the opposite way, too. I've seen it happen a hundred times, and you likely have too. I just thought the depressing story would lend some needed gravitas to all the stick figure pictures, you know?

👉To put it briefly:

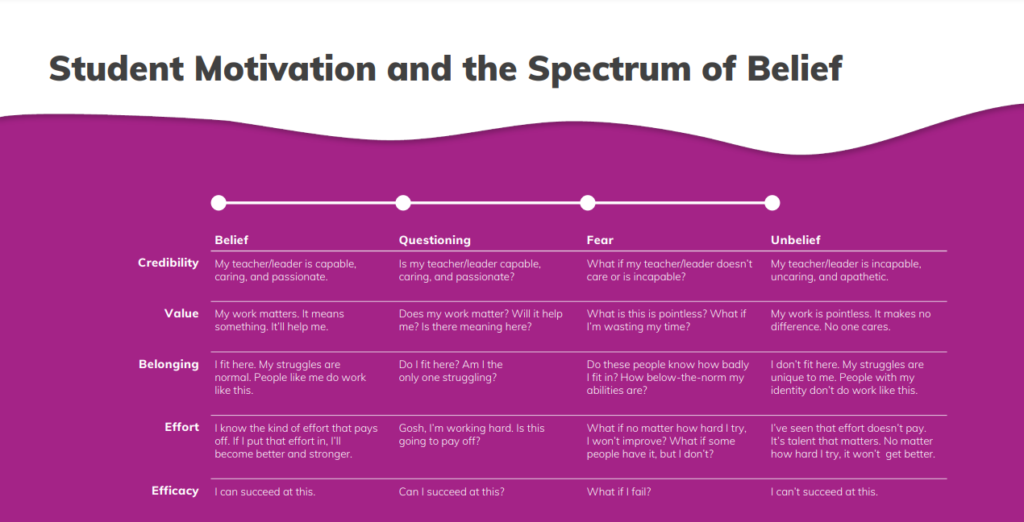

- The five key beliefs exist on a spectrum. In every student in your classroom and school, their heart is someplace in each of the rows of the following grid.

💡Why it's important to know this in a classroom:

- It's common for teachers to say things like, “Well, that student is just not motivated.” This spectrum idea teaches us that it's not that simple — which is really good news. It's more accurate to say, “At present, the student doesn't seem to believe

- that math matters (Value);” or

- that she can improve her understanding of science (Effort);” or

- that Ms. Smith is good at her job (Credibility).”

This is what I mean when I say that the five key beliefs methodology can help us analyze student motivation puzzles with far greater effectiveness than we currently tend to. Accurate analysis enables effective action.

🛠Try this:

- View belief work as the alleviation of fear more than the indoctrination of thought. Remember: you're after knowledge in the will, not knowledge in the head. Fear is situated not in the head — we often think our fears are illogical — as much as it is in the will — despite our knowledge, snakes or mice or spiders or heights or sharks still creep us out. This view helps you to feel empowered when you encounter demotivation in your setting.

3. The five key beliefs are not all equal in power.

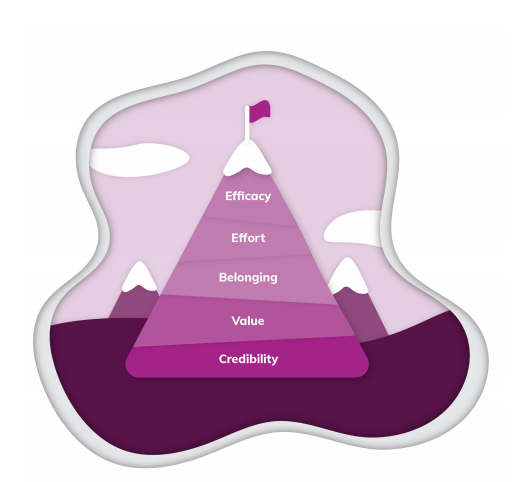

That last section was super long, so in this one I'm going to let a picture be worth a thousand words or so. The image above came from the brilliant designers at Dezudio, whom I met through the good folks at Brooklyn Lab Charter School recently. [1]

The image shows how the beliefs relate to one another in a classroom that is focused on student mastery. [2] Note that Credibility is darker than Value, and Value is darker than the remaining three. Also, note their positions on the mountain.

👉To put it briefly:

- Value is more foundational to student motivation than Efficacy, Effort, or Belonging — after all, why do I care if I belong or can succeed if I think that English class is just a pointless waste of time?

- Credibility is the most foundational of all. It's a place from which you can have unique influence over the other four.

💡Why it's important to know this in a classroom:

- The five key beliefs can be overwhelming to a teacher when learning about them for the first time. What I always say is that if you can only focus on one of the beliefs, focus on Credibility. It's especially malleable, it's the most within your control, and it's the point of best leverage from which to influence the other beliefs.

- With that said, once you get a handle on all the beliefs, you're going after all of them all the time in the context of the mastery work you're doing with students.

🛠Try this:

- For a rapid improvement in Credibility no matter where you are in the school year, try the student-by-student ground game.

4. They are dependent on context.

I don't know if it's possible to overexaggerate four things about the classroom context:

- How important it is to cultivating student motivation and therefore student mastery;

- How complex it is;

- How little control we have over the entirety of it; and

- How nonetheless massively powerful our little slice of control is.

Remember that thing about each of our students being souls — hyper-complex amalgamations of five distinct parts of being? Now multiply that by every other person in the class and take that and multiply it by every experience any of these people has ever had.

It's kind of like what happened when they pointed the Hubble telescope at the same spot in the sky for 50 days in a row. If you held your thumb at arm's length to cover the moon, the patch Hubble pointed at was “about the size of the head of a pin.” [3]

So what happened? Previously dark portions of sky turned out to be littered with GALAXIES. There were thousands of them. Galaxies have about 100 billion stars in them apiece. 100 billion of our suns, multiplied by 1000s, multiplied by all the rest of the next sky beyond the pinhead sized spot Hubble looked at.

Some scientists — scientists — even go so far as to say that the number of stars in the universe may be infinite. Basically: we've still got lots to learn here.

That's how the classroom context is. The more you learn about teaching and people and your discipline and yourself, the more you're like, “Wow. There is a lot happening here.”

So, like the universe, one way to look at that is, “Wow. I'm existentially horrified right now.”

But the way you and I want to look at it is this: we have a methodology for understanding how to find signal within that noise; we have a lens filter that helps us to see the layer of motivation and intervene intelligently. The five key beliefs help us turn chaos into concepts that we can actually use in our daily work.

👉To put it briefly:

- The classroom context is complicated — rather than decry that, we ought to roll up our sleeves and get to work understanding the parts of it we can best influence. Beliefs are largely context-dependent — especially in K-12 students. How we shape the school or classroom context is enormously predictive of the degree to which students will pursue mastery with care.

💡Why it's important to know this in a classroom:

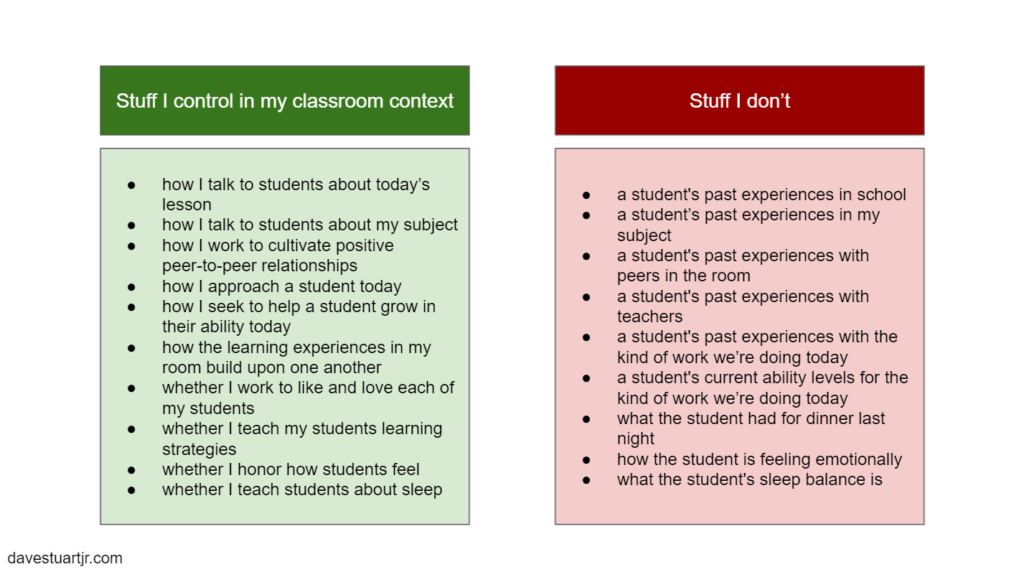

- You only control so much in a room — a sliver of the total context — but what you do control is massively important. Be sure you know the difference between what you do and don't control in your context.

🛠Try this:

- Think of your work as a teacher partly as the work of sending consistent signals. Amidst the complexity of a classroom, we want to be consistently producing messages — in our words and our actions, our lessons and our assignments, our policies and procedures — that we're credible, that the work is valuable, that each student belongs here, and that smart effort can yield growth and success.

5. The five key beliefs are malleable.

The research is clear: these things can shift. They can shift in a week, in a month, in a year. They can shift for a week, for a month, for a year. A student can go from demotivated in science class in September to scheduling elective science classes in February. A student can think you're the worst teacher ever and after a five-minute conversation be back to finding you credible.

This doesn't mean students are fickle — it means people are. And that's not a knock on us, either — heck, we're kind of like gardens.

👉To put it briefly:

- The beliefs are malleable, which means comments like “So-and-so is just a demotivated student” aren't the final word. You and I have a big impact on the five key beliefs.

💡Why it's important to know this in a classroom:

- It means we can do things about hard circumstances! It means there's hope — lots. Even in — especially in! — Fall 2021.

🛠Try this:

- In the next five weeks, I'm going to give you five guides to influencing the five key beliefs in the first few weeks of school. Once they're live, I'll link to them here. (Update they are done!🥳)

- Three simple, robust methods for establishing teacher CREDIBILITY in first week of school

- Three simple, robust methods for establishing teacher VALUE in first week of school

- Three simple, robust methods for establishing teacher BELONGING in first week of school

- Three simple, robust methods for establishing teacher EFFORT in first week of school

- Three simple, robust methods for establishing teacher EFFICACY in first week of school

Want them all in your inbox? Newsletter folks are always first to receive new articles — subscribe here.

Footnotes

[1] Basically, for the past few years Brooklyn Lab has brought together experts from around the world for a rapid iteration “charette” process in which experts answer a question facing schools. This year's question was basically, “In light of all that's happened the past 18 months, how can schools best create thriving cultures in Fall 2021 and meet the unique and diverse needs of each student?”

You will be shocked at my answer: “Well, we've got to equip and empower all teachers with the five key beliefs methodology.” You can see the slides that resulted from my answer and those of the other folks in the charette super soon — I'll update this spot with a link when it's available and I'll be sure to mention it in future newsletters.

[2] Now notice: I said a classroom focused on mastery. If your classroom is focused on other elements of the student soul — say, the social element, or the emotional element — then the power dynamics within the five key beliefs might be different. Belonging might be most important in such a setting. Maybe. I am not sure because my work is pointed at promoting the long-term flourishing of young people by teaching them to master the disciplines and the arts. When I treat social and emotional learning, it's a side mission, not the main mission.

[3] I can never write or speak about this picture — the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field — without getting lost in a rabbit hole. It is a cool rabbit hole. You should go in it. Here are some sources:

- How many galaxies are there? (Space.com)

- Video showing the zoom in from our visible constellations to the XDF image

- Explainer on the significance of the XDF

- My Google calculation of one of the estimates of how many stars there are in the universe

- Most amazing Hubble discoveries

- How many stars are in the universe?

- Core of Omega Centauri image – NASA explainer

Zachary says

Well, there’s at least a non-zero chance that I am now going to find myself questioning my belief in the reliability of untested chairs… But aside from that, what a rich dive into the understanding of beliefs and how they affect our work in education! Never stop writing about this topic, Dave!

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Zach, this is incredibly encouraging my friend. Take care.

Diane Wanamaker says

Alleviating fear, rather than indoctrinating thought. Wow. That makes a powerful difference in how I go about trying to cultivate beliefs. As always, thanks Dave!

Dave Stuart Jr. says

See you soon, my friend.

Jim Woehrle says

The saga of Mr. Stuart and Johnny Johnson would be hilarious if it weren’t so true. I feel seen.

Great stuff, Dave.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Hahaha — it is so much better when you label it a saga, Jim 🙂