In The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own, I lay out an approach to student motivation in which Five Key Beliefs can be influenced using just 10 basic strategies.

The eighth of those strategies is Define Success: Wisely, Early, Often.

- What is it?

- How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

- Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

- Where do I start?

- Should it just be me defining success for students, or students defining success for themselves?

- I have a student who is completely uninterested in succeeding. What should I do?

- I have a student who has told me their parent/guardian doesn't care about their success in school. What can I do?

What is it?

- Define — that is, “state or describe the exact nature, scope, or meaning of.”

- Success — that is, “the aim or purpose of an endeavor.” Most of our students are not clear on what the aim or purpose of history or math or science or Spanish is. I know that seems crazy to us folks who live and breathe our subjects, but it's true.

- Wisely — that is, “in a way that shows experience, knowledge, and good judgment.” When I was an early career teacher, I did not have a wise definition of success. I was one of those “everyone should go to college” people. As my experience and knowledge grew, I started to think more clearly and inclusively about what success looked like for each student.

- Now my definition of success for high schoolers in general is contained in something my colleagues and I came up with one year, the “four pillars of high school success.”

- Early — that is, starting tomorrow, starting at the beginning of the lesson, starting at the beginning of the unit.

- Often — that is, one-and-done won't do it.

Like all of The Will to Learn strategies, this isn't complicated. It's common sense. BUT because it's so common, we don't do it commonly enough. As a result, our students flounder for lack of clarity.

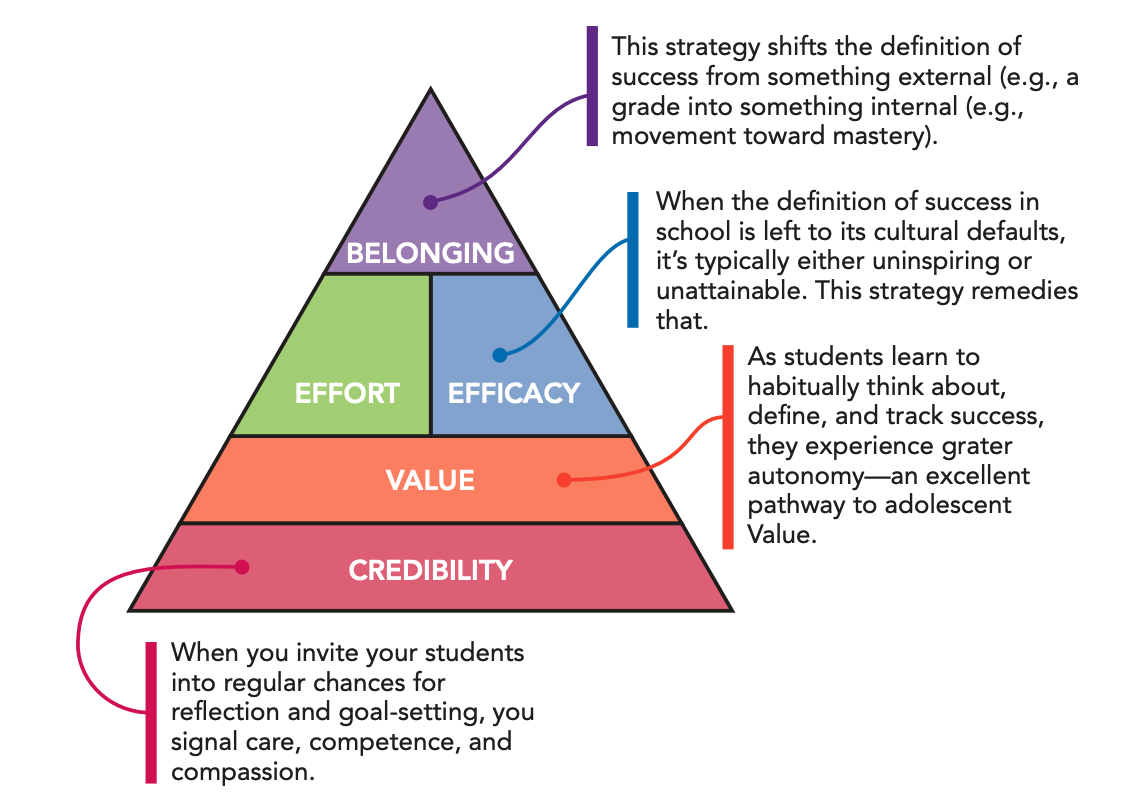

How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

While the Define Success strategy is found in the Effort and Efficacy chapter of The Will to Learn, it has an influence on other beliefs as well.

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

Where do I start?

Start with an Everest Statement that summarizes an overall picture of what your whole class is aiming at. I've got a complete guide on Everest Statements here, and I treat them at length in Chapter 1 of These 6 Things.

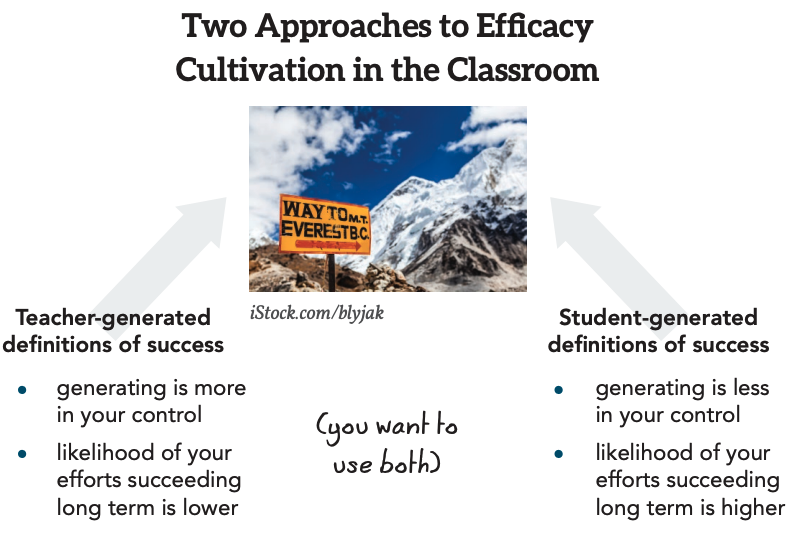

Should it just be me defining success for students, or students defining success for themselves?

It should be both.

For teacher-generated definitions of success, keep them brief and clear, just like you do with Mini-Sermons. Use your Everest Statement for a general, big-picture sense of success, and use daily “success criteria” for lesson-level clarity.

To get my students generating their own definitions, I use prompts like this:

- What does success look like for you this school year? What’s a reasonable and specific and meaningful goal that you have for yourself this school year?

- What kind of person do you want to be one day? What could you do this [lesson, week, unit, semester] to work toward becoming that person? How could success in this class contribute to your long-term success as an individual?

- Fill in the blanks: Lots of people my age talk about success as if it’s just about __________. For me, however, it’s more about _____________.

These are not fancy questions. But when asked regularly — during warm-ups, during lesson chunk transitions, at the end of class — they begin to shape your students’ definitions of success into something far more likely to be both attainable (Efficacy) and meaningful (Value).

It's also helpful to periodically guide your students in the WOOP (or GOOP) goal-setting exercise, which I describe here.

I have a student who is completely uninterested in succeeding. What should I do?

Back in the 1980s, researcher Raymond Wlodkowski (1983) conducted a study that asked teachers to converse with target students for two straight minutes on a nonacademic topic, 10 class days in a row. This “2×10” intervention, Wlodkowski found, was remarkably predictive of improved classroom dynamics going forward. And while I know of no peer-reviewed replication of Wlodkowski’s results, there are hundreds of testimonials online of teachers who have used this strategy to great effect over the past 30 years.

To me, Wlodkowski’s 2×10 method is perfect to use with a student who seems especially resistant to defining success. To begin, take a class roster and select the student you are most concerned about. That phrase — “most concerned about” — deserves a bit more explanation. Here’s how I select students for a 2×10 intervention:

- Is there someone in class who seems especially uninterested in thinking of success in any way? (This is our current scenario.)

- Is there someone in class who seems more prone than others to learning-disruptive behaviors?

- Is there someone in class who seems more prone than others to disengaging from a certain mode of work in class (e.g., reading independently, participating in group problem-solving conversations, elaborating during public speaking exercises)?

- Who in my class seems the most socially withdrawn from the rest of the group?

Now obviously, questions like these are bound to lean toward my biases. Because of this, I like to keep track of who I do a 2×10 with over the course of a semester. This allows me to periodically review whom I’ve selected to see if my selections properly reflect the various diversities in my classroom.

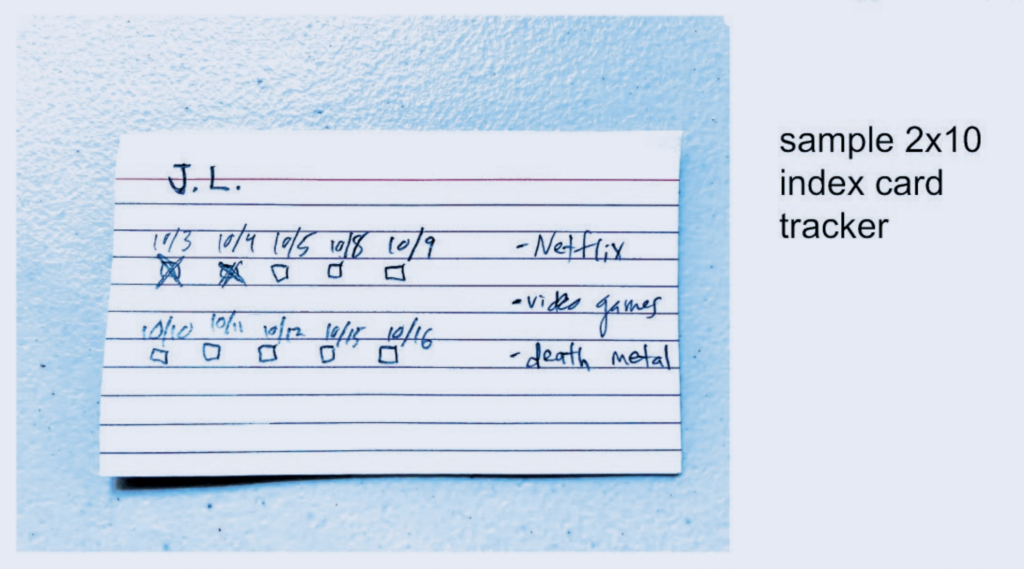

Once I’ve selected a student, I take a blank index card, write the student’s initials on it, and make a set of 10 checkboxes with the next 10 dates of instruction on it. As I complete each day’s 2×10 with the student (often during an independent work segment of the lesson), I make notes of any nonacademic interest that the student alludes to (example below).

I like to tape these onto my desk right next to my computer where I take attendance. Sometimes I have an index card for each of the class periods I teach.

During the first few days of a 2×10 intervention, I find the work to be very challenging. Target students tend to be uncomfortable speaking with a teacher at length — and trust me, two minutes is quite a length at first! I approach those early conversations by saying things like this:

- “Hey, Ruben, I was just thinking the other day that I don’t really know much about you and I would love to. Nothing crazy — just, say, what do you like to do when you’re not in school?”

- “Carlei, I notice that you’re always drawing in my class. I know, I know — sometimes I’ve gotten on your case for that. But I realized the other day that I’ve never asked you about how this interest came to you and how you got so good! Tell me about it.”

Almost always I find that by the third or fourth day of a 2×10 sequence, these conversations become much more comfortable and natural.

- “Ruben, I looked up that show on Netflix that you mentioned, the documentary that you said is really sad. Holy cow — just watching the trailer made me sad! How did you come across that documentary, anyway? I don’t often meet students who watch documentaries in their spare time.”

- “Carlei, I made this doodle the other day during a meeting I was attending — just like you said, it actually kind of kept me focused on what I was hearing! Do you have any cool new drawings or doodles today?”

What’s remarkable is that by the end of the two weeks, you’ve invested only 20 minutes of total class time and almost always have arrived at a place unthinkable with that student only weeks before. Why does 2×10 work so well? I suspect that part of it is because students we’re concerned about are not used to receiving consistent, nonthreatening attention like this from a teacher. They begin to look forward to the interactions and see us as someone who genuinely cares (rather than someone who is seeking to engineer a relationship for the sake of making their job easier).

Now, of course, it’s up to you and me to make sure these attempts are as genuine as we can possibly make them. Don’t overlook this important internal work.

I have a student who has told me their parent/guardian doesn't care about their success in school. What can I do?

For something like this, I think two things are important:

- First, even if your student feels that their guardian doesn’t care about their success, you should not make the same assumption. We, as educators, can’t assume anything about a student’s home life or family situation except that students’ guardians do care about their success just as much as their teachers.

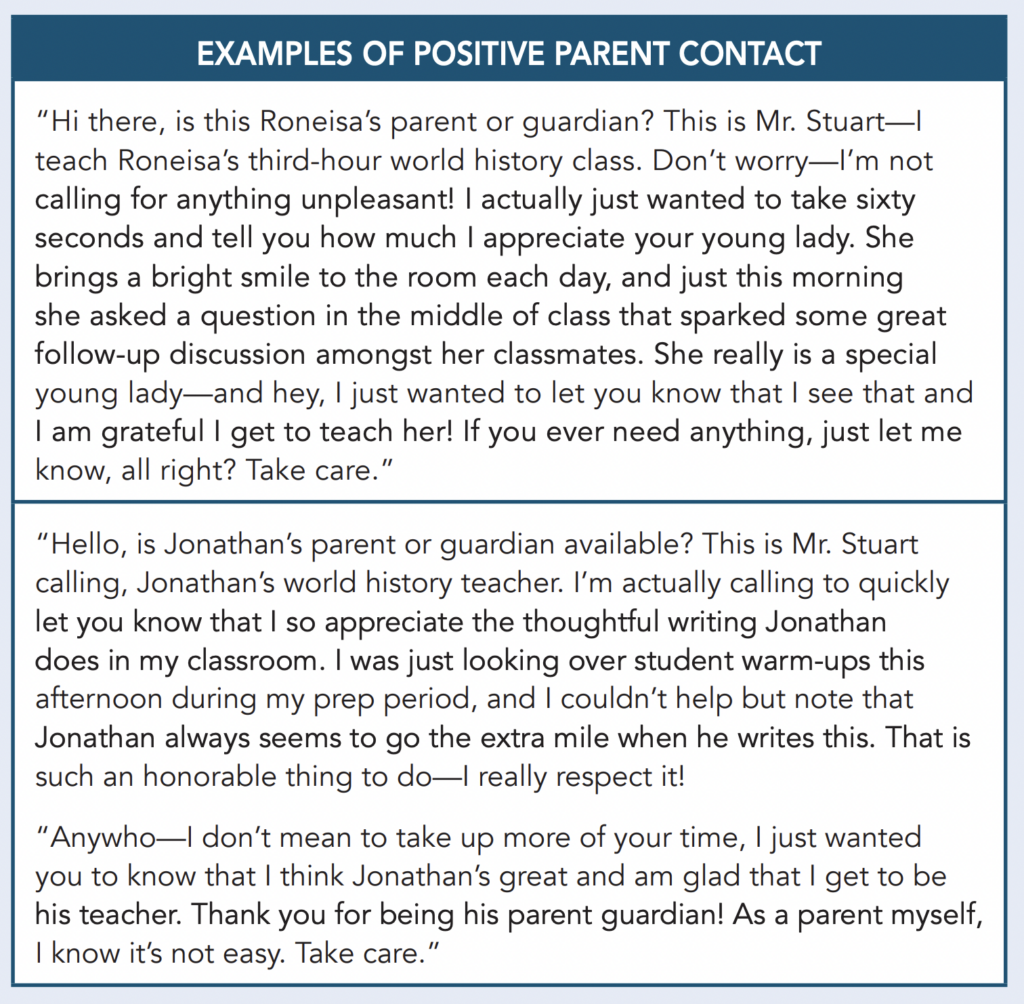

- Second, try making a positive parent connection (via phone or e-mail) about something you specifically appreciate about the student in question. Since this is such a low-effort task, I’ve spoken with many teachers over the years who make positive parent contact a part of their daily routine.

Here’s how a teacher from Baltimore describes this process:

I like to do this via a quick phone call at the end of my work day. I keep a clipboard sheet just for this purpose, right next to my phone. Using the (not always perfect) data that I have for each student, I attempt the phone numbers on record. Whether I get a voicemail or a live person, I leave a simple message sharing something that I specifically appreciate about the parent or guardian’s student.

In terms of the Five Key Beliefs, in these brief interactions, that teacher is signaling to guardians that he genuinely cares about the student and is grateful to have the student in his class.

In my own attempts at this kind of strategy, this is what these positive parent phone calls can sound like.

Jason Schultz, a secondary educator at Divine Savior Academy in Doral, Florida, does something like this but digitally. Every day before he leaves work, he looks at his “Before I Leave” checklist. One of the items on that list is “Send a parent/guardian e-mail.” Jason peruses the document where he keeps track of these e-mails, selects a student he hasn’t e-mailed yet this school year, and writes a quick paragraph or two very much in the spirit of the examples I shared above. When I was leading a workshop at Jason’s school and he shared this strategy with me, he said he had lost count of the number of times he’s heard back from a parent about how much these e-mails mean.

Both of these methods—phone or e-mail—take roughly five minutes per workday and result in about one contact attempt per student home per year. To me, this is a no-brainer transaction because you’re significantly widening the reach of your Care signaling. It’s now not just to your students but also to their homes — and this inevitably leads to more discussion outside of your classroom about the fact that you are a good teacher that cares about each student. So in that sense, it helps with Credibility.

But to bring it back to our hang-up, when dealing with students who are telling you that success in school is not something their parent or guardian cares about, these positive touchpoints between the home and school make it more likely that school will be viewed as important at home.

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: You get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply