Classroom management — that is, creating an environment in which student behaviors are conducive to enjoyable and productive learning — is the first hurdle a teacher must cross in order to implement the approach to teaching I describe in These 6 Things and The Will to Learn. If a class is unruly or unsafe, it is very difficult to do the things I describe in those books. And while the simple approaches to good teaching I explain in those books will help with classroom management, those books do not treat the particulars of classroom management that I use in my own classroom.

For the sake of transparency, I am not a classroom management expert. But thankfully, I know someone who is, and I flew that person to my classroom several years ago to film a comprehensive course on the subject. Lynsay Mills Fabio is a New Orleans educator who once reached a classroom management rock bottom. Her administrator told her that if she didn't improve in classroom management, her job was at risk.

Thus began Lynsay's zero-to-hero journey, in which she developed the foundational skills and structures needed for classroom management:

A Classroom Management Plan: Rules and Consequences

Effective classroom management begins (but doesn't end!) with a two-part plan:

- What are the rules in this classroom?

- What are the consequences for breaking those rules?

Rules for Classroom Management (Part 1 of Your Classroom Management Plan)

When I drive to my house from school, there are certain rules I have to follow:

- Stay on the right side of the road.

- Use my blinker when turning.

- Obey the speed limit.

These rules don't exist because the government is trying to micromanage me. These rules exist because they enable the safe and productive functioning of the road system.

These rules work because they are:

- As simple as possible, but not simpler

- Clear and actionable

This is what you want your classroom management rules to be like. What basic behaviors are needed for you classroom to function in a productive and enjoyable manner? You want your list of rules to be as short and as clear as it can be.

Sometimes, teachers make their list of rules very short but not very clear.

- E.g., “I have one rule in my classroom: respect yourself and others.” While this is certainly short, that word “respect” is not very clear. It leaves room for argument. Imagine if the speed limit in my neighborhood was “drive at a safe speed” rather than “25 mph.” Driving speed would vary greatly in such a scenario, officers would have a much harder time giving tickets, and tickets would be much easier to challenge in court. It sounds nice to give drivers this level of discretion, but it is not practical.

This is the list of rules Lynsay recommends. She garnered these directly from educator Michael Linsin of the Smart Classroom Management blog.

- Listen and follow directions.

- Raise your hand before speaking or leaving your seat.

- Keep hands, feet, and objects to yourself.

- Respect your classmates and your teacher.

- Use technology as indicated by the teacher.

This list of rules is longer than the non-examples I showed above, but each rule does a lot of work in making the environment stabler and safer.

- Listen and follow directions. This rule allows me as a teacher to direct student energies toward productive ends.

- Raise your hand before speaking or leaving your seat. This rule allows me to have some control over the airspace of my classes of 30+ students. In the past, I've experimented with leaving this rule out, instead teaching my students to monitor their own voices and be aware of the others in the room. I have found that this is not something I can reasonably expect 30+ adolescents to be proficient at. If I don't have this rule, then even one to three “blurt-prone” students in a room of 30+ can significantly reduce the enjoyability and productivity of the learning environment.

- Keep hands, feet, and objects to yourself. I teach ninth graders, so I do not feel a need to explain why this rule is needed. I will say again, though, that even one to three students disregarding this boundary on a given day can significantly reduce the enjoyability, productivity, and sense of safety in a lesson.

- Respect your classmates and your teacher. “But wait, Dave — didn't you say ‘respect' is too wishy-washy a term?” I did. But when situated amongst the other rules, I can now be much more specific when I'm addressing a problem with respect. For example, if I'm facilitating a Pop-Up Debate and a student is making faces across the classroom at a peer, that student can argue that they are listening and following directions (because I've probably not said “don't make faces across the room”) and so on. But despite this, there is still a problem — they are doing something that indicates a lack of respect for the student who is speaking.

- Use technology as indicated. Technically, this is a repeat of Rule #1. But because of the many problems that can come up as soon as a Chromebook turns on, I find it helpful to address technology in its own rule.

If you'd like to use this exact set of rules, here's a poster I made.

Consequences for Classroom Management (Part 2 of Your Classroom Management Plan)

For the first few years of my career, I got stuck on consequences a lot. If you're not careful here, you end up creating power struggles, resentment, and lots of extra work for the teacher.

Here is what Lynsay recommends, based on the recommendations of Michael Linsin. This sequence is used per class period. (Lynsay and I both teach in secondary settings.)

- First infraction: Warning + reduction of one of two daily professional points. (More on professional points below.)

- Second infraction: Relocation to a temporary seat + reduction of remaining professional point.

- Third infraction: Communication home regarding specific rule(s) broken + documentation in school discipline tool.

Professional points are something some colleagues and I incorporated upon studying Michael Linsin's blog. The idea is that, when students contribute rather than detract from an enjoyable and productive learning environment by following class rules, they receive two professional points per day. These go in the Classwork category of my gradebook, which makes up 40% of the student's semester grade. Because I put everything else we do in class (outside of summative assessments) in this category, it is filled with hundreds of potential points by the end of the semester. Things like quizzes, articles of the week, discussions — they all go in here. So losing a professional point or two per week doesn't really move the needle on a student's grade. However, it does give them a small, extrinsic reward for conducting themselves in a professional manner by adhering to the “workplace norms” that are contained in the rules.

In schools that use standards-based grading (SBG), this wouldn't work. In the past when I've not used professional points, I still get good results with the consequence list above. I do find that adding the professional points helps, however.

This is the portion of my approach to classroom management that I get the most nitty-gritty questions on. Some of those are:

- What if a student goes past three infractions in a lesson? For cases like these, it depends what's going on. In rare cases, I may send the student in the hallway for a moment until I can talk to them. In others, I may note it in the discipline log for the day, give my admin a heads up that I may need support on the following day, and then use that admin support as needed.

- What if you don't have admin support? In cases when I've not had supportive admin, I'm left to my own devices. The key on questions like these is not to get lost in the weeds and instead focus on the critical elements I've placed elsewhere on this page and on my blog.

- What if what if what it what if? It's not the rules and consequences that make a well-managed classroom — it's the moves that prevent misbehavior, moves that respond well to misbehavior, the warmth, the Five Key Beliefs, the well-structured lessons, etc. Don't let outlier scenarios keep you from implementing a plan.

What's most important with the consequences is that you teach students beforehand how the rules work and how the consequences work. You remind them as the year progresses that consequences are not personal. When a police officer hands me a ticket, it's not because she hates me. It's because I was driving in a manner not allowed by the rules of the road; her job is to ensure that roads remain safe and productive. My job, when it comes to the rules, is similar: I'm ensuring a productive and enjoyable learning environment. When I give the consequences, I want to remain emotionally neutral and matter of fact.

In other words: do everything you can to make rules and consequences a clinical, matter-of-fact concept. There is no reason to ever shame a student with these things — everyone has off days, some more than others. We can have grace for those off days while at the same time administering the rules and consequences fairly.

Teaching the Rules

On the first day of school, as briefly but clearly as you can, you want to teach your students:

- What are your rules

- Why do they exist (to support an enjoyable and productive class time)

- What happens when they're broken

Once you've taught this, begin to use the system.

Quick Reminder

At this point, my more constructivist colleagues may feel horrified at the cold-sounding approach to rules and consequences that I am advocating. Dave, why aren't you asking the students to develop the rules? Don't these cold lists of rules and consequences suck the life out of your room?

I use this method because of what I've seen, experienced, and researched in my practice. These are the simplest and most efficient means I am aware of for laying a foundation for an enjoyable and productive learning environment. I have experimented in the past with student-created classroom rules. The trouble I've had with this is that it takes a lot of time and the results vary widely. It's a lot of work for me to keep track of a different set of rules for each of my several classes.

The quick reminder is, the rules and consequences are only a small piece of a well-managed classroom. Approaching them in the way Lynsay Mills Fabio and Michael Linsin recommend has been the most successful approach to rules and consequences that I've found in my career.

Teacher Moves That Prevent Misbehavior

Next, Lynsay focuses on teacher moves that prevent misbehavior. Though you'd need to enroll in her Classroom Management Course to get detailed instruction on how to implement these, I'll give brief descriptions below for the purposes of this page on classroom management.

- Authoritative Presence: The idea here is that the way the teacher uses their body, voice, and word choice has a big effect on student behavior.

- For an in-depth article on authoritative teacher presence, check this out. For a video, go here.

- Threshold: This is the age-old idea of meeting your students at the door at the start of class. This establishes the context of your room and the enjoyable and productive environment it contains. It also gives you a chance to have a Moment of Genuine Connection or two.

- Assigning Seats: Rarely in my career of teaching secondary students have I found that student-selected seating works best. It's not never happened — for example, in the 23-24 school year, I had remarkable success with student-selected seating in the final quarter of the school year — but it's rare. I assign seating using a variety of methods (e.g., intentionally placing students based on skills, dispositions, or behavior patterns; randomly placing students) and a variety of frequencies (e.g., at the start of the year, I change student seating almost daily; once we hit October, I change seating once per unit).

- Radar: The idea here is that the teacher is regularly scanning the room and that the students see the teacher doing so. This gives the teacher information on what's going on, what's working, what's not, and allows the teacher a good chance to intervene in cases where students are getting off track or veering toward breaking the short, focused set of classroom rules.

- Clear directions: Many student misbehaviors are born when teachers give poor directions. Elements of poor directions include: not clear, too long, too complicated, students being asked to do something they don't yet know how to do.

- Narrate compliance: “I see ________ doing _______. I see _______ doing _______.” This is a way of influencing students toward behaviors that are conducive to the enjoyable and productive learning experience you're trying to facilitate.

- Plan reminders: “All right — we have two minutes remaining in this small group discussion — two minutes.” Or “Students, in about one minute we are going to submit our warm-ups and close our Chromebooks — one minute.”

What Lynsay emphasizes repeatedly in her course is that, because these are embodied teacher moves, it is helpful to rehearse these moves in advance of using them. That's right — close your classroom door and practice using these moves just as you would when students are present. This lets your body get used to them and builds your confidence before you implement them with students in the room.

Teacher Moves That Respond to Misbehavior

No matter how good I am at teaching, misbehavior still happens. All that I need to approach this misbehavior with grace and emotional neutrality is to imagine what it's like being a student. Class after class, day after day, cognitive demand after cognitive demand — it's a tiring job. Not to mention, of course, that for many of our students, school is far less motivating than that crush sitting across the room, that friendly rivalry with their partner, that video game they can't wait to play, that cell phone with 100 notifications since last passing period. There's plenty of reasons for students to get off track. Here are the moves Lynsay recommends for handling these:

- Give a consequence: This one's first because we did anticipate students would misbehave when we developed our list of group-protecting rules and consequences. The idea with this is to practice giving consequences matter-of-factly and consistently.

- Blank I need blank: This one explains itself. “Johnny, I need your spiral notebook out and opened to a fresh page.” Or “Susan, I need you to close your Chromebook.” This move is often accompanied by consequence.

- Proximity: Another age-old teacher move, and it could have just as easily gone in the “preventing misbehavior” category as this one. The idea is that the closer the teacher's body gets to a student, the more likely that student is going to alert themselves to what's going on and what they're expected to be doing.

- Stop and stare: Notice, this is not the death glare. It is neutral eye contact in which the teacher is looking at a student who is off-task.

- Non-verbals: For example, I use a closing motion to indicate that a student's Chromebook should be shut, or a hands-down motion when I want a student to hold on to their question until a better time.

- One more time: When more than a few students transition poorly from one learning activity to the next, it's best to have the whole class do the transition over again than it is to try handling consequences for a handful or more students. This segues nicely into our next topic: procedures.

Procedures for Classroom Management

Lynsay recommends creating classroom procedures for any activity that 1) happens often and 2) involves the whole class. In other words, think routines — things you want your students to grow so accustomed to that they do it without thinking.

In her course, Lynsay uses this analogy from Ronald Morrish in his book With All Due Respect: Why do we stop at red lights? You might think, “So that I don't get a ticket,” or “So I don't get hit by a car.” But most of the time, we stop at red lights because we always stop at red lights. We do it without making a choice — it's an automatic behavior linked with the stimulus of a red light.

This is what we're after when developing, teaching, and reinforcing procedures.

Now, because developing, teaching, and reinforcing a procedure is a lot of front-end work, we've got to be careful not to overwhelm ourselves and our students with these. Here are some basic procedures Lynsay recommends.

- Entering class: There's nothing as energy-sapping to me as a chaotic start to a class period. The core idea in my classroom is that the bell is all that we need to know that it's time to begin the warm-up. Prior to the warm-up, students may calmly visit with one another, get their materials out, preview the warm-up activity (on the screen), and let me know they are going to use the restroom. Once the bell rings, I teach my students to not need me to begin the warm-up — the bell is all that we need. I frame this as something that gives them autonomy and avoids the annoying pattern of the teacher having to quiet the class down and get started after the bell rings. I tell them, “The bell is our boss. When it rings, we're expected to begin our work of learning. When it rings again, we're expected to move to our next class. There's no wiggle room, it's just a matter of fact — the bell is our boss.”

- For a deeper treatment of this one, check out this article: The Teacher's First Test of the Day, Part 2 (Or How to Boost Your Credibility and Sanity with a Clear and Reinforced Start-of-Class Procedure).

- Coming to attention: Lynsay does the countdown thing: “3…2…1…All pencils down, all voices off, eyes on me.” Other methods include the teacher raising their hand and students doing likewise. Whatever you choose as a method for bringing students to attention, teach them exactly what it looks like, and then practice it to excellence each time it happens. I like to remind them that the reason we do this is because they don't need another educator noisily bringing the room to attention. We are after an enjoyable and productive learning experience.

- Think-Pair-Share: Think-Pair-Share is one of those things I used to assume I could simply ask my high school students to do without teaching them how to do it. But just like anything else in teaching (e.g., Pop-Up Debates), the level of quality students are able to produce is closely linked to the level of instruction, modeling, examples, non-examples, and feedback I use with my students.

- Independent Practice: When students engage in independent work in your class, what should that look like? Just like with the others, you explain to them the purpose of independent work, what it does and doesn't look like, and then you practice it with them each time it happens until it becomes automatic.

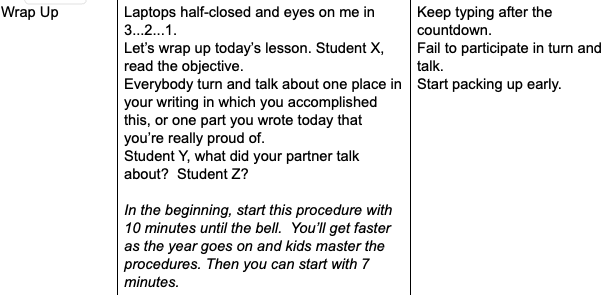

- End of class: Here you'll actually have a few procedures lumped together, such as wrapping up a work task and discussing the lesson objective with a partner. Below, you can see the level of clarity Lynsay brings to wrapping up — what the procedure is and what examples of not following the procedure look like:

Now, of course, you can develop, teach, and reinforce as many procedures as you want. Just be careful not to drive yourself crazy.

With any procedure you develop, the important thing is to introduce it clearly, have students practice it, and then reinforce it over time with feedback and “One More Time” (see Moves That Correct Misbehavior above) as needed.

Warmth: How to Create a Well-Managed Environment That Is Also Warm and Welcoming

Finally, we get to a critical question: how do we run our rooms using the methods above without it feeling like a soulless exercise in human robotics? The answer is warmth, which Lynsay and I boil down into four basic elements:

- Constancy: This is the quality of being faithful and dependable. What we don't want is for our own emotional turbulence (anger, frustration) to make waves in our classrooms. We want to be the constant, not the variable. This is hard because, despite our best efforts in the areas above, we will have students each year who aren't able to reach the levels of success we're after with our classroom management plans. Our job in these cases is to love and respect these students as we continue to work with them. This requires a lot of inner work on the part of a teacher, reflecting on things such as: I've got great influence over my students, but I am not omnipotent; teaching is a beautiful and important calling, but I need to cultivate a life outside of my classroom as well; dealing with the shame and embarrassment that comes with “failing” in the classroom and interpreting it not as evidence that I'm a failure but instead as evidence that I've got more things I can practice.

- Awe: We want our classroom to provoke awe in our students — to provoke curiosity, excitement, interest, and engagement. These are things that my Five Key Beliefs approach to student motivation can accomplish. For a deep dive on that, check out my book or this article.

- Relationships: Early in my career, I used to rely entirely on relationship for classroom management. That was problematic because it led to students feeling coerced into learning-conducive behaviors. What I needed was the Plan, the Moves, and the Procedures pieces we've outlined above. But with that said, relationships are still a beautiful and integral piece of a warmly managed classroom. They are not the point of teaching, but they are one of its greatest rewards.

- For a super simple yet powerful method for cultivating solid working relationships with all students, consider trying Moments of Genuine Connection. For that one student in the class that's extra hard to work with, try 2×10.

- Excellence: Often, we don't link the idea of teaching toward excellence with warmth. Instead, we associate excellence with the more demanding side of teaching. But in fact, excellence can be a key part of a warm approach to teaching when we simply do the following: teach our students to do something they didn't think they could do, and then, once they've done it, allow them to bask in the glow of having done something so difficult.

- My favorite tool for creating this is Pop-Up Debate, which you can learn more about in this guide and in the argument chapter of These 6 Things.

This CARE Framework for warmth — Constancy, Awe, Relationships, Excellence — provides both the foundation and the capstone for a well-managed classroom.

What questions do you still have?

Submit your questions in the comments section below, and I'll update this article with my best answer.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Kate McCook says

This post is great in its clear, straightforward approaches to classroom management that are also laced with warmth and understanding. Thanks for summarizing all these moves in one place before the start of the year, Dave. I don’t see the link to the rules poster–am I missing it or can you try linking it again?

Thanks!

Kate M.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Hi Kate! You’re not missing anything — I’m waiting on Etsy to open up my store. When it’s live (any day now, fingers crossed), you’ll find it here: https://davestuartjr.com/etsy

Dave Stuart Jr. says

It’s live! You can now find the poster here: https://www.etsy.com/listing/1766069883/classroom-rules-dsjr-classroom-poster?click_key=1039570c184b8cf8f6065dca68611270c1cce547%3A1766069883&click_sum=318d69b5&ref=shop_home_active_8

Barb Hale says

I’ve got a class that is kicking my butt. My thought was “What would Dave do?” I had the article “13 Non… ” in my inbox still. I read it and saw a link somewhere to this. I kind of think the link just materialized because I needed it! This article was just what I needed. I’m going to stew a bit over our long holiday break and come back fresh in January! Thanks for coming through for me yet again.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Of course my friend Thank you for saying hi!

Thank you for saying hi!