The Belonging belief forms the fourth and final layer of the Five Key Beliefs of student motivation, which I unpack at length in The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own and in Chapter Two of These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most.

- What is the Belonging belief?

- The Key Ideas About the Belonging Belief

- Key Idea #1: Belonging signals are ambiguous.

- Key Idea #2: The way students interpret signals of Belonging becomes recursive if left untreated.

- Key Idea #3: Belonging is especially challenging for underrepresented students because of two related but separate phenomena: imposter syndrome and stereotype threat.

- Key Idea #4: Like the rest of the Five Key Beliefs, Belonging can be positively influenced using simple, wise methods.

- How can I cultivate the Belonging belief in my classroom?

- Common Questions and Hang-Ups About the Belonging Belief

What is the Belonging belief?

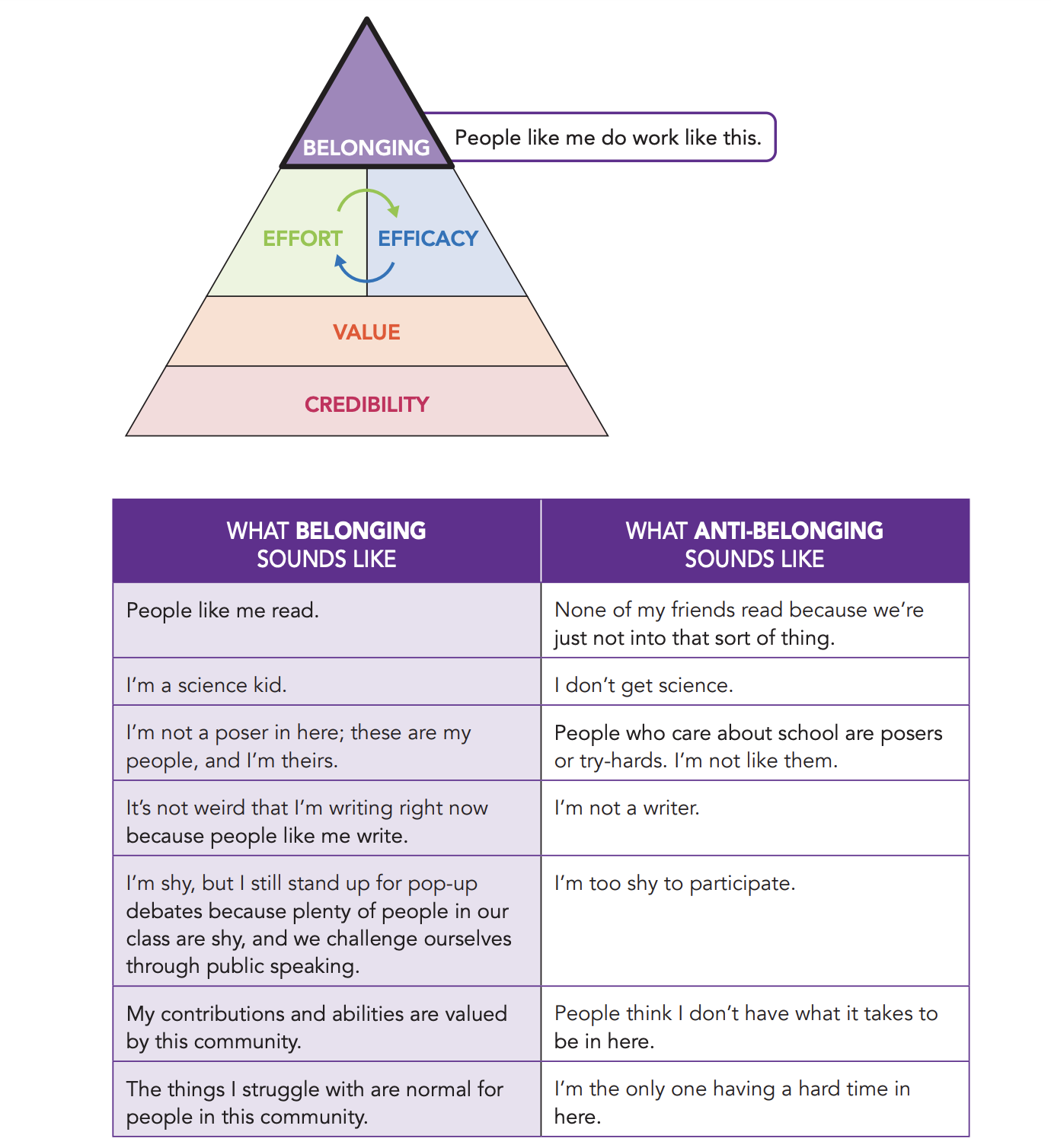

Our final belief — the capstone of our Five Key Beliefs pyramid — is Belonging. It largely comes down to two sorts of questions in the hearts of our students:

- Who am I? What is my identity? What makes me, me?

- Does who I am fit here — with these people, studying this discipline, doing this kind of work?

Years ago, I called this the Identity belief because the question “Who am I?” is so central to its nature. Yet Belonging isn’t just about the individual — it’s just as much about the group and the context. It’s not just “Who am I?” It’s:

- “Who am I in this context?”

- “Who am I with these people?”

- “What do the things that happen to me in this classroom mean?”

- “How do I fit here?”

Whenever I think about Belonging, I typically think of three stories. Two of them involve my children and one involves my students. The first story is funny; the second and third are magic.

In the first story, my daughter Laura and her siblings and I were doing post-dinner chores. It was a Monday evening, so the kids’ chores had rotated since the previous week.

“What are you on this week, Laura?” I asked.

“Hmm, let me check.” A pause. “Oh no!”

“What!?”

“Vacuuming!? I wasn’t born to vacuum, Dad!! I am not a vacuum person.”

Laura perfectly (and humorously) demonstrated the important power of the Belonging belief: It’s hard to be motivated to do work that does not fit with your identity.

In the second story, we head to the backyard swimming pool of Ms. Rita, where she taught a legendary survival swim school for children for over 30 years. Most students began the week of five one-hour lessons terrified of swimming, unwilling even to put their heads under water. By the end, over 90 percent of Ms. Rita’s students were capable swimmers growing in their confidence. All four of our children were fortunate to have Ms. Rita as a teacher.

After our children completed the swim school, strangers would often ask us at pools and lakes how we got our children to swim with such confidence and joy. The truth is, it was about five hours of very basic, simple, and effective instruction and practice. This transition from fear to empowerment led to a shift in how our children thought of themselves in relation to water. In other words, it was a shift in Belonging. All of our children shifted from saying, “I hate going in the water,” to affirming, “I’m a swimmer.”

A teacher did that.

And for the third story, we head to a nondescript classroom in rural-suburban west Michigan: my own. Rebecca’s story isn’t uncommon. At the start of the school year, Rebecca was worried sick during our first Pop-Up Debate. “I felt like I was going to throw up” were the words Rebecca used when I asked her about it. But as the year progressed, I worked to normalize the struggle (Strategy 10 in The Will to Learn) of public speaking anxiety and Woodenize (Strategy 7 in The Will to Learn) the living daylights out of all aspects of Pop-Up Debates (see Chapters 4 and 7 of These 6 Things or this guide). And as time went on, some remarkable shifts began to happen in Rebecca’s heart:

- She grew in confidence.

- She started looking forward to Pop-Up Debates.

- She began standing up in the debates without being called upon.

- She began using her extra, non-mandatory speech opportunities.

- She started to think her future may be one in which public speaking was a central part. (In other words, she was starting to believe in the deep Value of public speaking, too.)

In all of these stories, we see the powerful role that Belonging plays in motivation — in things as minor as vacuuming to those as consequential and scary as swimming or public speaking.

Belonging stories like these happen in schools around the world every day. I once met an art teacher in the Phoenix area named Carlos, and he told me the story of a student he taught who was very much into playing football. At the start of the semester, this student was quite vocal with Carlos about how he wasn’t much of an artist. But then the student came into class one day to share with Carlos what he had noticed about the shading on a mural that had just been completed in his neighborhood. “Well,” Carlos said to the student, “you sound an awful lot like an artist when you talk like that.”

The student grinned.

Now let’s look at some key understandings for the Belonging belief.

The Key Ideas About the Belonging Belief

Key Idea #1: Belonging signals are ambiguous.

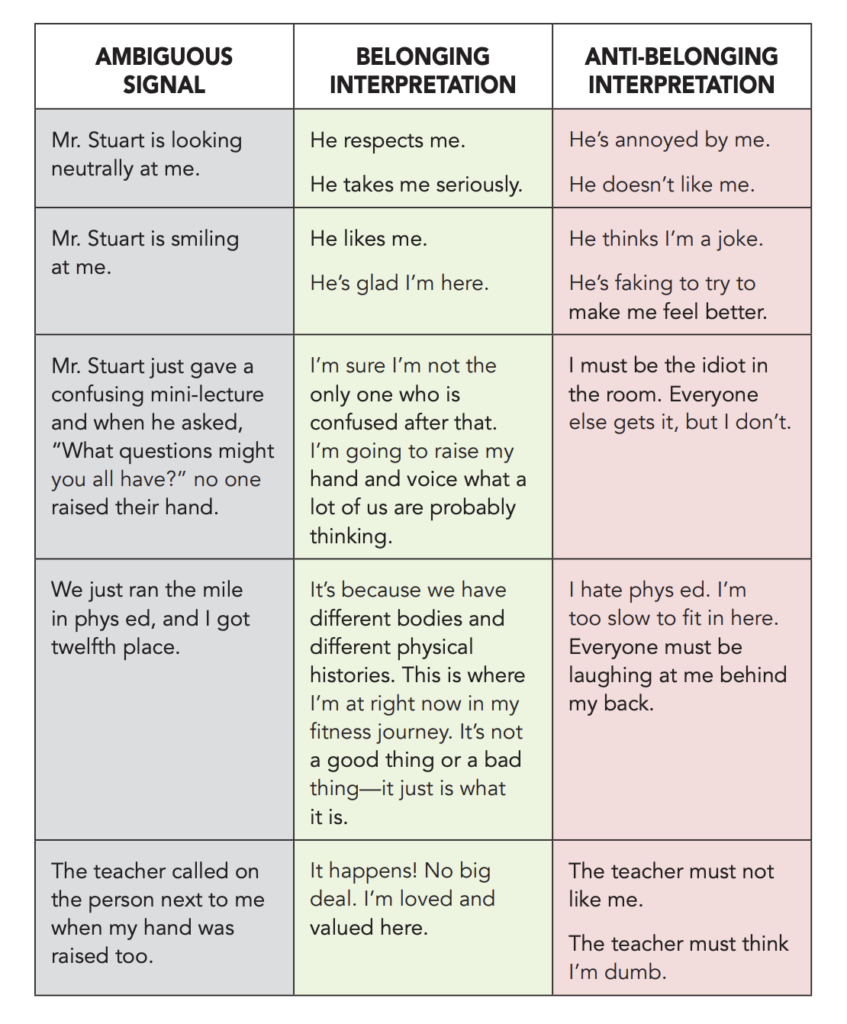

If I walk up to you and have a neutral expression, what does that signal to you? Does it mean that I respect you? That I’m glad to see you? That I’m annoyed by you? That I find you repulsive? Or what if I walk up to you and smile? Does it mean that I respect you? Is the smile genuine or fake? Am I glad to see you, or am I trying to hide that I’m annoyed by you?

This is the trouble with signals in social contexts: They are ambiguous. They require interpretation. And in contexts as socially complex as schools, wow — what an overwhelming array of ambiguous signals all of us will find ourselves confronted by.

So what the Belonging belief does is create a powerful lens through which to interpret ambiguous social signals — it turns them into motivators; it makes them safe. Anti-Belonging, on the other hand, does the opposite — it interprets ambiguous signals as signs of threat.

Key Idea #2: The way students interpret signals of Belonging becomes recursive if left untreated.

Because Belonging signals are ambiguous, much of a student’s sense of Belonging lies in how they interpret those signals. If the interpretations are helpful — see the green column above — then the students’ sense of Belonging will be strengthened over time in a manner akin to the flywheel effect that we saw at play with Effort and Efficacy (see p. 170 and following in The Will to Learn).

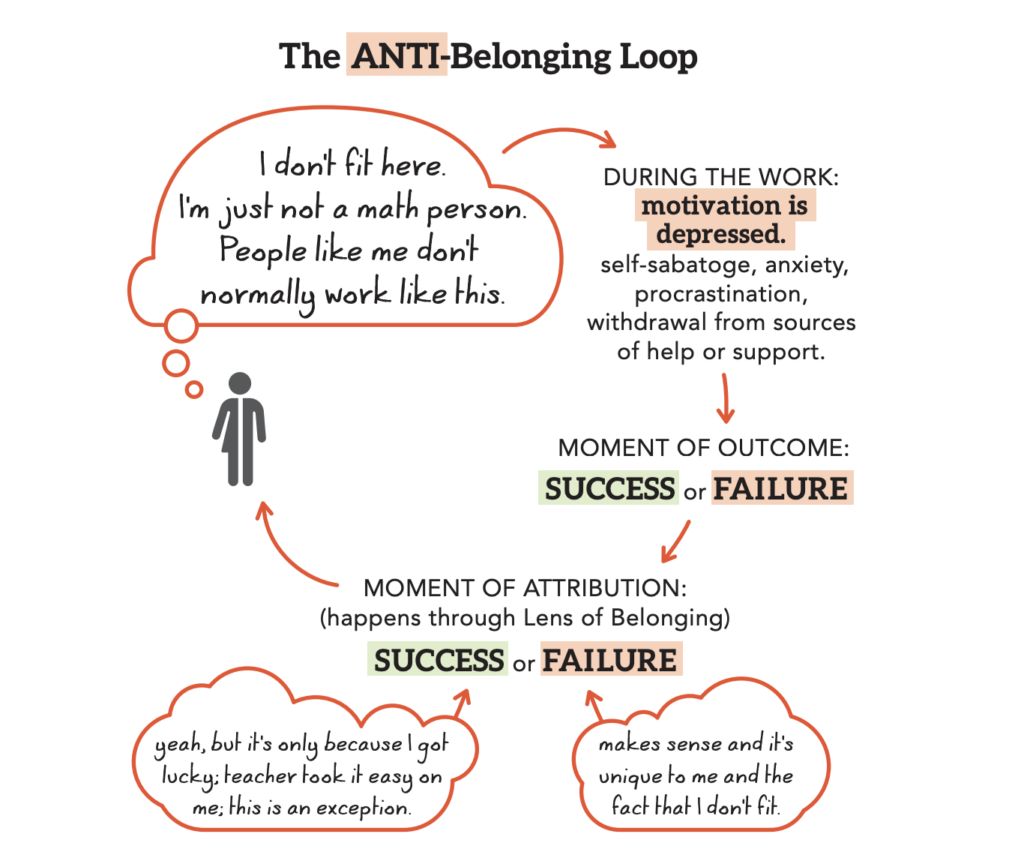

But if the interpretations are not helpful — see the red column above — then the student’s sense of Belonging will diminish over time in something we could rightly call a doom loop. Here it will be easiest for me to explain using a graphic.

In the upper-left corner we have a student in, let’s say, a mathematics class. The student has just begun his tenth-grade year with Mr. Modisher, and because of a multitude of experiences and factors that Mr. Modisher could not control, this student enters the class believing things like we see in the thought bubble above.

Over the course of the first week, Mr. Modisher does his best to use the strategies outlined in this book, but our focal student is one who has struggled with Belonging in mathematics for many years. This will not be an overnight change for the student. And so during those early math lessons and assignments that Mr. Modisher provides the student with, the first byproduct of anti-Belonging rears its head: The student has a hard time being motivated to try to learn. This demotivation comes from things such as the following:

- The Hamster Wheel Effect — The student is so concerned about not fitting in here that he or she is hyperaware of how folks nearby may be perceiving him.

- Self-sabotage — To protect himself, the student may put forth as little effort as possible; after all, this way he doesn’t need to face the disappointment of effortful failure.

- Procrastination — The student could find it difficult to attend to Mr. Modisher’s lessons or homework until the very last minute; after all, no one wants to face the feeling of anxiety that a high schooler experiences when they don’t fit in.

- Isolation — When Mr. Modisher circulates to confer with individual students, our focal student may bluff his way past Mr. Modisher’s offers of guidance, saying he doesn’t need help.

Eventually, the first formative assessment results start to come back. The student sees that he’s getting questions wrong — lots of them. Or perhaps the first unit of the year is quite remedial — perhaps the student surprises himself by doing well. This is where anti-Belonging bears its second unpleasant fruit: the moment of attribution. How is the student likely to interpret the outcomes of this first week of class? Because our student has a heavily entrenched anti-Belonging belief — and because of the ambiguity of Belonging signals — he is likely to interpret either success or failure in the same way — proof that he doesn’t belong.

If he fails — the more likely outcome due to the demotivation we saw in the “during the work” phase of the loop — then he will likely interpret the failure as further proof he doesn’t fit. It will reinforce his belief. But if he succeeds — very possible, given Mr. Modisher’s skillful scaffolding during this initial week — he’s likely to brush it off. He might think Mr. Modisher was just being nice to the students, or he was making it too easy. Or perhaps our focal student was just lucky.

And so the cycle continues.

Thankfully, there are simple tools for remedying situations like this over the course of a semester. In fact, every single one of the strategies in The Will to Learn ministers to students who are caught in hard spots like our focal student:

- Will to Learn Strategy 1 — Track Attempted Moments of Genuine Connection (MGCs) — helps Mr. Modisher build a strong working relationship with the student. As time progresses, the student will grow in his perception that Mr. Modisher genuinely cares about his academic progress, and this will help the student take advantage of Mr. Modisher’s offers for help.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 47-63 in The Will to Learn, pp. 30-32 of These 6 Things, or this DSJR Guide.

- Will to Learn Strategy 2 — Improve at One Thing — has allowed Mr. Modisher to become an effective teacher during his career. As a result, Mr. Modisher is accustomed to working with tenth-grade students who are underprepared for tenth-grade mathematics, and he has strategies that he’s developed over time for helping them catch up.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 64-90 in The Will to Learn.

- Will to Learn Strategy 3 — Gentle Urgency — means Mr. Modisher has more minutes to use for helping students like our focal student make gains and catch up. This also communicates to the student over time that math might be more valuable than he previously perceived.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 91-100 in The Will to Learn.

- Will to Learn Strategy 4 — Mini-Sermons — has Mr. Modisher regularly commenting, in ways that line up with his personality, on how good and useful and even beautiful mathematics is. Our focal student hasn’t seen this before and is intrigued by it.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 123-141 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Will to Learn Strategy 5 — Feast of Knowledge — allows Mr. Modisher to sprinkle in stories from teaching his own children basic mathematics as they were growing up. This lets Mr. Modisher teach his tenth graders tricks for mastering basic math facts under the guise of sharing something he did with his children rather than as a bald-faced attempt to help his students fill in missing pieces.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 142-156 in The Will to Learn or Chapter Three of These 6 Things.

- Will to Learn Strategy 6 — Valued Within Exercises — means Mr. Modisher is regularly asking his students to explain for themselves what the Value of mathematics is. He has them answer the “When will I ever use this?” questions and celebrates novel answers to such questions with his students.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 157-166 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Will to Learn Strategy 7 — Woodenization — is so powerful for our focal student because Mr. Modisher takes the time to teach every kid in the class how to do really basic things that the student thought only he didn’t know. For example, Mr. Modisher teachers the basics of using a calculator, how to avoid common mistakes with multiplication, and other general things that our focal student assumed no one else still needed to learn.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 175-193 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Will to Learn Strategy 8 — Define Success (Wisely, Early, and Often) — helps our student gain a vision for this mathematics class that he’s never had before. Slowly, he’s sensing that success in math, just like success in life, is about steady growth over time and about learning from setbacks.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 194-205 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Will to Learn Strategy 9 — Unpack Outcomes, Good or Bad — helps our student see that everyone in class reflects on how things go in each unit. It’s not just something non-math-inclined kids do. He starts to overhear the things other students are saying and begins to realize that almost everyone has at least some struggles during the growth journey of mathematics.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 206-218 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

Key Idea #3: Belonging is especially challenging for underrepresented students because of two related but separate phenomena: imposter syndrome and stereotype threat.

Imposter syndrome, first named by Clance and Imes in 1978, is the feeling students have when they are convinced they don’t belong and are in fact acting fraudulently when engaging in a given academic pursuit. This could happen to a student in an honors mathematics class who does not believe they ought to be in the class because no one else from their social group is there. Imposter syndrome can lead students to behave in various ways that further undermine their sense of Belonging.

Clance and Imes observed the following “four different types of behaviors performed by women with imposter syndrome that perpetuate the phenomenon. The first behavior is engaging in diligence, which refers to women working hard to prevent others from discovering their status as an imposter. The second behavior is engaging in intellectual inauthenticity, which refers to women choosing to conceal their true ideas and opinions, and only voicing ideas and opinions they believe will be well received by their audience. The third behavior is engaging in charm, which refers to women seeking to gain the approval of their superiors by being well liked and perceived as intellectually special. The fourth and final behavior is avoiding displays of confidence, which refers to women being cognizant of society’s rejection of successful women and consciously exhibiting themselves as timid” (Edwards, 2019)

Stereotype threat is related but different. Coined by Steele and Aronson (1995), this phenomena happens when a student is concerned about confirming negative stereotypes that may be held about their group. In their original research, Steele and Aronson demonstrated that Black students performed more poorly than white peers when made aware of negative stereotypes associated with their racial group and that this gap in performance diminished when researchers took steps to alleviate the phenomena.

Both imposter syndrome — the feeling that one does not belong — and stereotype threat — the feeling that one must prove that they do belong — amount to similar experiences for the learner: anxiousness about fitting in, hyper-vigilance to signals of Belonging or anti-Belonging, and an unpleasant hamster wheel in the mind and heart.

Thankfully, these experiences can be improved for our students. Let’s look at one quick method in the research for doing this, and then I recommend checking out the Normalize Struggle strategy (see pp. 231-241 of The Will to Learn or this guide) for a more robust treatment method.

Key Idea #4: Like the rest of the Five Key Beliefs, Belonging can be positively influenced using simple, wise methods.

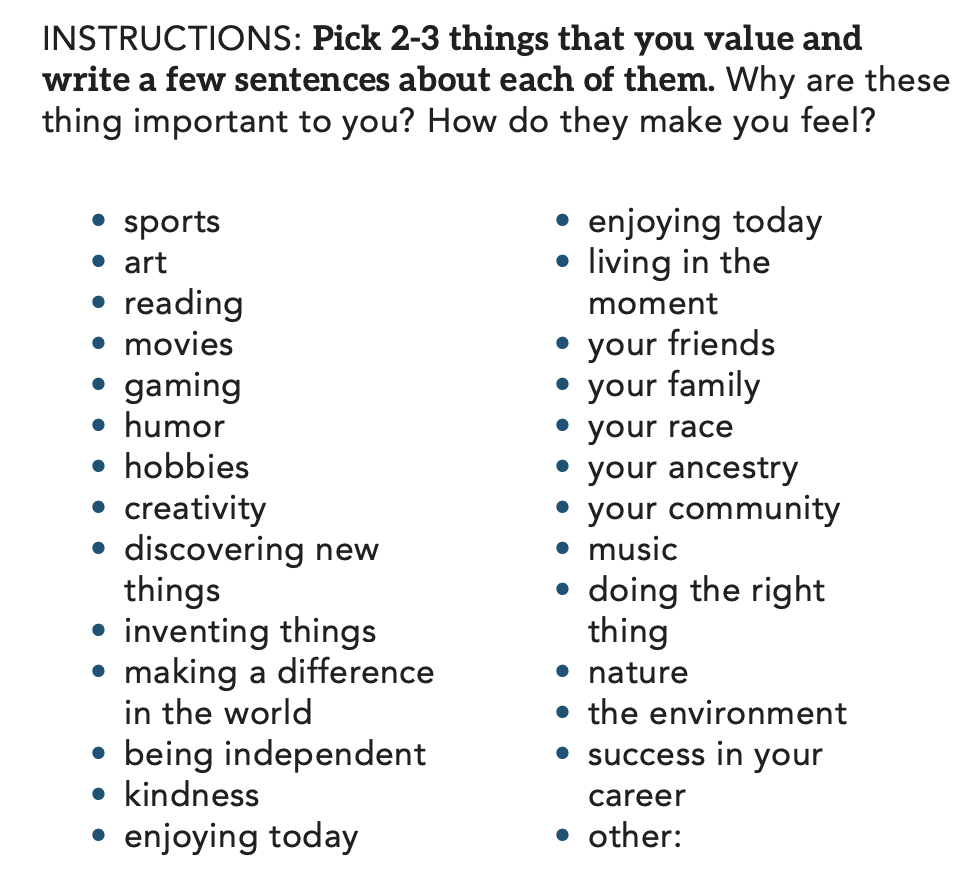

Let me give you an example from the research. This is called a “Values Affirmation” intervention.

Here’s all that you do: Give your students 15 to 20 minutes to write about two or three things they personally value. To get them thinking, it’s often helpful to give them a list — I like to do this on a screen up front — of potential values to pick from.

That’s it. There’s no need to discuss or share or anything else.

This remarkably simple exercise has been demonstrated in the research to have profound effects on Belonging. For example, in one study (Pyne and Borman, 2020) of 2,000 middle school students across 11 racially diverse middle schools, students did this activity twice in the school year, once at the start and once during spring testing season. In the months after the intervention, “The black-white suspension and office referral gaps were cut by two-thirds, with an even more positive impact on black students with prior infractions.” In other studies (e.g., Cohen et al., 2006, 2009; Miyake et al., 2010), students in stereotype-threatened groups who underwent this intervention earned higher grades over time.

As with all interventions like this, it is far from a silver bullet. But given the simplicity of the task and the wonderful things you can learn about your students, it’s a total no-brainer to incorporate this kind of thing into every secondary school in the world.

(I’ll never forget when Levi shared in his values affirmation write-up at the start of the year how much he valued riding his four-wheeler through open fields near his house. Before I read that, I had sensed in Levi a strong degree of anti-Belonging; he had written often in the early days of school about how he didn’t like school at all. But reading his poetic description of riding on the quad changed how I viewed Levi ever after. I found it easier to genuinely appreciate his presence in class, and this genuine appreciation was likely palpable to Levi during at least some of my MGC attempts for the rest of the school year.)

(For more on the Values Affirmation intervention, see this blog article.)

How can I cultivate the Belonging belief in my classroom?

At the end of this section, you'll see a list of articles I've written over the years sharing many ways you can cultivate the Belonging belief in your students. But when I wrote The Will to Learn, I was determined to identify the fewest, biggest-bang-for-your-buck strategies I could. I narrowed and narrowed and narrowed, until finally I had arrived at one core strategy for cultivating Belonging.

- Strategy 10: Normalize Struggle. The thing with struggle (e.g., nervousness in public speaking, stress about tests, difficulty writing, self-consciousness when exercising in Phys Ed) is that students often interpret it as something unique to them. They then take this interpretation and form a devastating and growth-halting conclusion: “I'm uniquely ill-suited to the work we do in this class.”

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 230-242 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR One-Stop Shop.

Extra “Booster” Strategies for the Belonging Belief

Outside of the core strategy outlined above, here is an ever-updating list of brief articles I've written to help you deepen your understanding and application of the Belonging belief.

- Next Year, Don't Start With Belonging

- Belonging Booster: Values Affirmation Exercise

- Using the Godfather to Help With Belonging

- Three Simple, Robust Methods for Establishing Belonging in the First Weeks of School

- Simple Interventions: Birthdays and Belonging

- A Simple Technique for Affecting Belonging, One Genuine Connection at a Time

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About the Belonging Belief

Lots of teacher books and blogs recommend starting out the school year by focusing on student Belonging. Do you recommend this?

I don't, for reasons I explain here.

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: You get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply