One of the biggest bang-for-your-buck Common Core standards is W.CCR.10, which basically says, “Write frequently for many reasons.” And the amazing thing about writing is that it achieves so many things simultaneously.

One of the biggest bang-for-your-buck Common Core standards is W.CCR.10, which basically says, “Write frequently for many reasons.” And the amazing thing about writing is that it achieves so many things simultaneously.

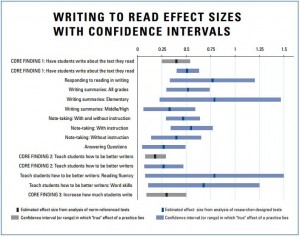

For example, in the “Writing to Read” meta-analysis report, researchers found positive effect sizes for all kinds of writing, ranging from the mundane (note-taking, summarizing) to the complex (click the image for a larger version). What was affected, you ask? Reading comprehension.

Writing, which Ted Sizer called “the litmus paper of thought… [and] the very center of schooling” is hugely helpful in the content areas, too.

Consider this study on the correlation between math achievement and writing, which Mike Schmoker shares in Focus:

In one middle school, 186 students were given multiple opportunities to explain and problem solve–in writing–as they learned math concepts. As a result, the percentage of students who met or exceeded performance standards on the state rubric rose from 4 to 75 percent in math knowledge, 19 to 68 percent in strategic knowledge, and 8 to 68 percent on math explanations (Zollman, 2009). As the author writes, “good teaching in reading and writing is good teaching in math.”

Or consider this study connecting science mastery with writing, conducted by Doug Reeves' Leadership and Learning Center in 2008:

In schools where writing and note-taking were rarely implemented in science classes, approximately 25 percent of students scored proficient or higher on state assessments. But in schools where writing and note-taking were consistently implemented by science teachers, 79 percent scored at the proficient level.

All right, enough studies (even though I love 'em) — let's get practical. How can we dominate Common Core writing through the simple, non-freaked out method of simply writing like crazy?

Always tie reading and writing together

When your kids read the textbook, a primary source document, or the article of the week, teach them how to take notes or annotate throughout (notice the difference in effect sizes between note-taking without instruction and note-taking with). When they are finished reading, have them respond through writing. Responses can be prompted as simply as, “What is the key point of this section? Why does it matter?” or as complex as, “What arguments are made in this article? How are they supported? Do you agree or disagree with them, and why?”

And remember, a paragraph or two of written response is awesome — it doesn't need to be longer.

One thing I would say not to do is simply tell kids to read Chapter 13, Section 2, and answer all of the questions at the back of the book. The questions and activities provided with textbooks are often designed by people who have never taught, and they are generally low- to zero-effective in helping kids become better readers, writers, and thinkers.

Instead, create your own response questions that are interesting and simple; these questions, like the examples above, should be along the lines of reading between the lines (inferring), arguing, making connections to other content, or drawing conclusions.

If you just do this — add writing to every reading task — and if you give kids one to two opportunities minimum to read complex texts every week, I'd be shocked not to see some serious gains in your kids in the areas of reading and writing.

Write more, grade less

“But wait, Johnny,” some of you are saying, with an apparent disregard for my actual name, “What you're saying is great in theory, but I have x number of kids in every class — I don't have time to read a bunch of essays.”

First of all, sir or madame, I am not talking about essays (yet).

Second of all, I agree with you that reading all of what I proposed in the preceding section is insane. My wife would justifiably cut the brake lines on my bicycle if I brought home every piece my students wrote.

Thankfully, I don't read everything they write. Not even half.

It all began one day when a hero of mine, Mr. Kelly Gallagher, said something like, “I only read about one of every four [non-process-written] pieces my students write.” He went on to say that his students never know which of their pieces he's going to read, so they stay on their toes while he stays sane.

Needless to say, that jives pretty well with not freaking out and working smarter not harder. I immediately adopted this sanity.

There are even more strategies for staying sane in Mike Schmoker's “Write More, Grade Less” article over at his website; here's a bullet-pointed list that you can expect to have explained for you by Mike:

- Teach one trait or feature at a time

- Assign and grade only one to three paragraphs for that trait only

- Have students peer edit for that trait only

Also a Jedi. - Assign shorter, one to two paragraph pieces as well as longer pieces

- Use exemplar models, both from students and professionals, to teach students the trait you're focusing on

- Vet thesis statements

- Vet outlines

- Have regularly scheduled “writing days” during which you read and grade papers while students read or write

- Have student pairs evaluate/revise good or bad sample pieces for a single trait

It's an awesome article. Read it.

Don't abandon extended papers

In the content areas, one to two longer papers each year is a good benchmark to aim for, and in English as many as one a month would be awesome (we average about .7 per month in our Freshmen Comp/Lit courses at my school). The length of these papers should increase with each grade level, and the bulk of the work should be done in class so we can walk around checking for understanding and ensuring student success.

The key for content area teachers is to remember that we are not English teachers — we're aiming for clarity and content, as Mike Schmoker says, as well as the ability to cite written sources to support arguments or conclusions with evidence.

The finer points of writing are up to ELA folks. But that's okay, because they are bards.

What do you think?

Is it possible to get more writing worked into your curriculum? Why or why not?

Kathy Nolan says

Dave, you really are outstanding and please, keep up the great work! You are impacting teachers in a big way! This movement will change our educational system as we know it making it better and more highly competitive. You are playing a significant role in that change!

Thanks for your work and sense of humor!

Kathy Nolan says

Too many explanation points…sorry!!!! I’m prone to fits of enthusiasm.

davestuartjr says

Kathy, both your exclamation points and your words are super appreciated — what a blessing to start my day with your comment! Thank you for such kindness, and I do hope this blog impacts teachers, schools, and students in the best ways. May truth win out over ignorance, hope over fear, and peace over freaking out 🙂

Thanks for your encouragement, Kath!!!!!!!!!!! 😉

Marge says

Every time I start to get freaked out about the upcoming year (which is often), I visit your blog and remember how to breathe. Thank you so much for sharing sensible and usable ideas, but more importantly, for always remembering the well-being of students is our most important objective.

davestuartjr says

Marge, you rock. Keep visiting and keep breathing and keep spreading the movement of folks who refuse to give in to the freak out 🙂 Thank you!

Kimberly says

Wait, I am the ELA teacher…so how often should my kids be writing? They are only responding, evaluating, annotating, etc. However, they are no essays and no grammar lessons. I am SO worried about this common core stuff!

Traci says

Amazing article! I love your approach to writing, reading, and grading! This makes me feel better about how I grade;) Thanks!!!

Robert Pitts says

Great article I like the idea. I can incorporate this in my lab reports as well

davestuartjr says

Robert, this is good to hear — thank you for sharing!

Janet Kimball says

A good article and I agree with having extended papers like research papers.