Recently, I posted an overview of the non-freaked out approach to the Common Core that I've been experimenting with in my ninth grade world history and comp/lit (ELA) classes during the last year and a half or so. In this post (Part 2), I'm going to dive into the what, why, and how of getting students to read, appreciate, and grow through grade-appropriate complex texts.

What are complex texts and why do they matter?

If you've been hearing “complex text” phraseology thrown around like crazy lately, it's because one of the central shifts that the Common Core promotes is the idea that, instead of only giving students books that are within their zone of proximal development (“just right” books), we should be asking students to read texts that are appropriately complex for their age.

(Check this out if you're wondering how “complexity” is defined by the Common Core.)

This doesn't mean the CCSS are opposed to things like choice reading or book love; rather, it stems from one of the central arguments in the research appendix (namely, that the average complexity of assigned reading in high school has been decreasing over the years, while the average complexity of required reading in college/career settings has been increasing).

Now, there's more than one way to tackle this Common Core shift. In this post, I'll primarily be sharing the approach I've chosen, but I'll end by addressing some common questions and an alternative approach that I learned of recently during a PD led by Penny Kittle.

But first, credit where it's due

I can take credit for about 1% of my approach. The following three people have heavily influenced my heart and mind; it is largely because of them that I expect so much of my students.

Rafe Esquith: a freaking knight

Since my student teaching days in Ypsilanti, MI, I've been inspired by Rafe Esquith's no-shortcuts-in-life, high expectations approach to teaching literacy. What does Esquith ask of his predominantly ESL fifth graders in a Los Angeles public school? In addition to performing an unabridged Shakespearean play from memory, they read the following complex texts as a whole class:

- Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men

- Twain's Huckleberry Finn

- Twain's Adventures of Tom Sawyer

- Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X

- Wright's Native Son

- Tan's The Joy Luck Club

- Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

- Stevenson's Treasure Island

- Dickinson's A Christmas Carol and Great Expectations

- Wiesel's Night

- Frank's Diary of a Young Girl

- Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird

- Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye

- Knowles' A Separate Peace

- Tolkien's The Hobbit

For any who liken such high expectations with bored, disengaged students, check out Esquith's classroom; if you assume this kind of shared reading would only burn out young readers, consider what Esquith's students go on to accomplish many years after leaving his class. And if you're tempted to think, “Well, my kids could never do that,” remember: these are ESL, free-lunch-eligible 5th graders.

Buy Esquith's book to get the whole story. Even though he teaches in an elementary context, few books have influenced my practices as a secondary teacher like his has.

Mike Schmoker: laser focus

Schmoker's Focus gives specificity and 6-12 applicability to Esquith's extraordinary approach. In the book, he lays out the three essentials for effective classrooms: a focused and coherent curriculum (what we teach); clear, prioritized lessons (how we teach); and purposeful reading and writing, or “authentic literacy” as he calls it. The book outlines an approach not just for ELA, but for science and social studies as well.

If you haven't read Focus yet, get after it. And if you're a Kelly Gallagher fan, here are his thoughts on the book:

“In an age where teachers are forced into the unrealistic pursuit of unobtainable standards, finally, a book emerges that cuts through the noise and helps us return to sensible, authentic teaching. Focus is insightful, practical, and, above all else, inspiring–a must read for all teachers, administrators, board members, and policymakers. Reading this book has made me a better, more reflective teacher. –Kelly Gallagher

Doug Stark: a master of efficiency and a personal mentor

Doug is a colleague, a mentor, and a friend in my current teaching setting. I was first impacted by Doug's teaching when I was given a class of freshmen in Trimester 2 of 2010 that Doug had taught in Trimester 1. I was blown away by how much the students had learned in the 12 measly weeks afforded by our trimester schedule. Since then, I've sought any chance I can get to learn from Doug's efficiency and effectiveness in teaching reading and writing to high schoolers. I also appreciate his straightforward approach to problem solving.

My approach in Freshman Comp/Lit: shared complex texts of varying lengths

So how do I make this complex texts shift in my classes? First, I'll share my approach in my 9th grade ELA class; later on, I'll share what I do in my 9th grade world history. Here are the complex texts we read in 9th grade Comp/Lit:

- Trimester 1: excerpts from The Odyssey; daily choice reading*; ~15 articles

- Trimester 2: Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet; Knowles' A Separate Peace; Achebe's Things Fall Apart; periodic choice reading (at least once per week)*; 7 articles

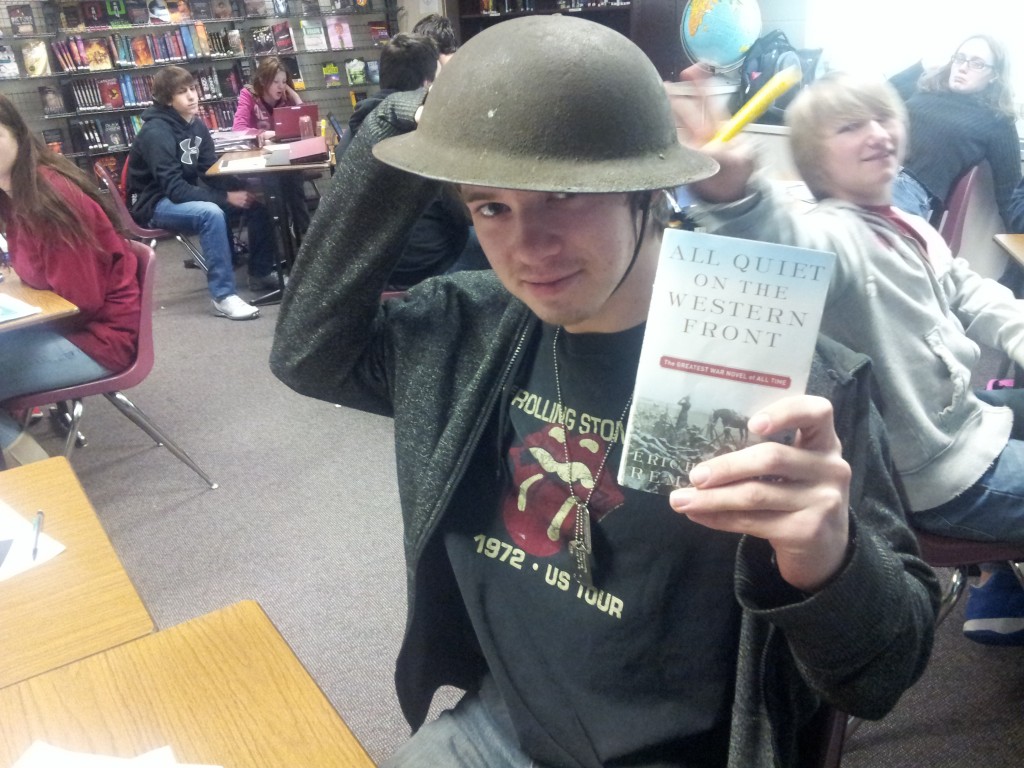

- Trimester 3: Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front; Orwell's Animal Farm; Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451; 7 articles

If you're wondering about my school's demographics, I teach in a rural setting with 65% of my students eligible for free/reduced lunch.

*A note on choice reading: The reading I have my students do here is strictly choice. Therefore, sometimes the books students choose are very complex; more often, they are not.

So how do we get students to read complex texts that they're not interested in?

The most common (and powerful) critique of the extended whole-class text approach that I'm using is this: most students just won't (or just can't) read grade-level complex texts on their own. Therefore, it's a huge waste of time to assign anything more than an article-length complex text.

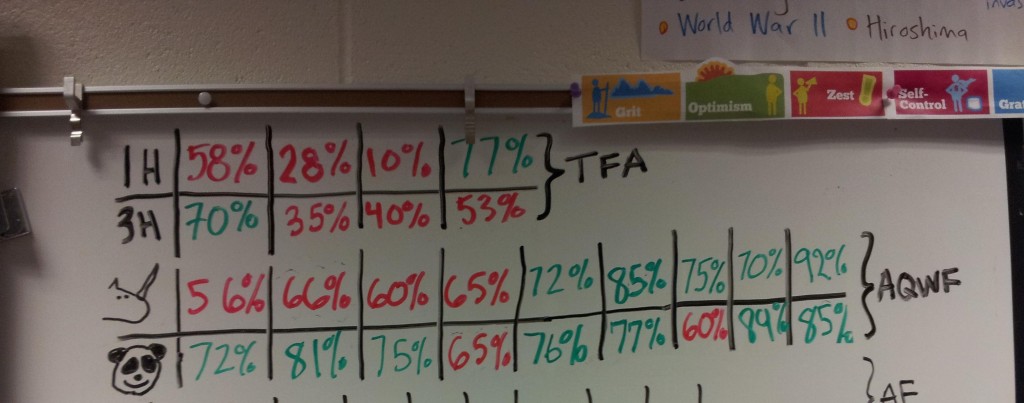

And indeed, if it's true that most students won't read what's assigned, it is a wasted assignment for most students. So, seeking to determine what percentage of my students were reading the assigned texts, I began tracking the percentage who had completed the previous day's reading assignment (see image below).

Let me give you a little context: last spring, only 46% of our Juniors scored at the college/career ready threshold in reading on the ACT. I know that some will scoff and say, “Well, the ACT is just another demon-possessed, mandated test,” but, to me, the ACT is at least a hoop my students must jump through in order to access college, and at best it's a time-tested, fairly reliable measure of how ready my students are for the demands of post-secondary life.

So, keeping that 46% in mind, I currently consider 70% the “win threshold.” As you can see above, Things Fall Apart — the first book I tracked — was pretty much a fail. However, we saw quite an increase in completion with our next extended complex text, All Quiet on the Western Front. If we can keep those numbers up during the remaining months of school, I'll be pumped. And I know that, even if students didn't finish the assigned reading, due to the way I've structured class, all are reading, writing about, and discussing large portions of it.

(If you're thinking, “100% is the only number that should be green on that board,” please read this article, in which Rafe Esquith differentiates between equality of opportunity and equality of results.)

So, here's the question: How do we get a vast majority of kids reading whole class, extended, complex texts? These are the strategies I'm using:

- Hook well: To get my students into an extended text, I use a pre-reading model that my colleague Doug Stark developed. Here's what I used for All Quiet on the Western Front. It includes anticipatory questions for discussion/debate, 8-10 key concept vocabulary words that I explicitly teach, and a choice of three personal narrative prompts that link to the key concept vocabulary.

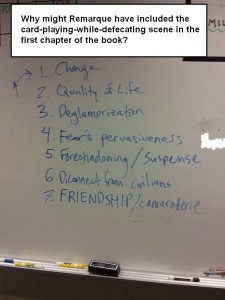

Start slow: More than once, I've felt pressure to cover a book quickly, and that pressure has led me to assign just as many pages at the beginning of a reading unit as I do at the end. This doesn't work well; many students quit. During the first few days of reading, I assign small amounts of pages (10 to 15), and I take time in the following days to closely read and discuss difficult portions from the preceding day's reading. For example, within the first few pages of AQWF, there's a scene where Paul and his comrades are enjoying a leisurely, communal card game in a field; disconcertingly, they are also defecating. I photocopy 4 pages from this section, have students highlight their confusion, have students discuss their confusion in their groups (I model how to clearly articulate one's confusion and how to helpfully work through it as a group), and then we discuss confusions as a class. Finally, I ask students to brainstorm why in the world Remarque includes this scene [and they come up with awesome theories (see image at right)].

Start slow: More than once, I've felt pressure to cover a book quickly, and that pressure has led me to assign just as many pages at the beginning of a reading unit as I do at the end. This doesn't work well; many students quit. During the first few days of reading, I assign small amounts of pages (10 to 15), and I take time in the following days to closely read and discuss difficult portions from the preceding day's reading. For example, within the first few pages of AQWF, there's a scene where Paul and his comrades are enjoying a leisurely, communal card game in a field; disconcertingly, they are also defecating. I photocopy 4 pages from this section, have students highlight their confusion, have students discuss their confusion in their groups (I model how to clearly articulate one's confusion and how to helpfully work through it as a group), and then we discuss confusions as a class. Finally, I ask students to brainstorm why in the world Remarque includes this scene [and they come up with awesome theories (see image at right)].- Simple reading checks at the start of each class: I ask a question before we begin each day's reading lesson. In crafting these questions, I aim to see if my students have a basic comprehension of a major event or concept in the assigned reading; put another way, I usually only ask a question about something that the author used several pages to develop or portray. This question isn't intended to be a “gotcha”; in fact, it's not uncommon for a few of my students to write “I didn't get that far” or “I wasn't able to read last night.” These checks help me figure out who's struggling with doing the reading, and who's struggling with comprehending the reading. (Here are the responses I received for this reading check: What awkward event happened in the hospital room? Remember, I teach freshmen!)

- Model reading: During the first few days of reading a text, I will read 1-3 pages of the day's assignment aloud and model my thinking with whatever is most difficult about the text. In Things Fall Apart, I'll model my confusion with the rhythm of Achebe's prose, or with how the text seems to randomly jump around. In All Quiet, I'll model using the glossary, dealing with Remarque's subtle use of flashback, or whatever else is raising flags for my students.

- Simple homework assignments: There are two basic things I want students to habitually do when we read complex texts. First, I want them to ask questions (see “Q & A Session,” below). Second, I want them to record quotations and paraphrases that connect to our key concept vocabulary (this makes our summative assessment a million times easier). Here's an example of a reading assignment for AQWF (this simple sheet is another brainchild of Doug Stark); one of these sheets will often cover several nights of homework. If this homework seems simple, that's exactly my hope; as Marzano shares, “Parent involvement in homework should be kept to a minimum” (Classroom Instruction that Works, 2001).

- Q and A session: Using their reading assignment sheets, my students discuss their questions from the previous night. I expect everyone in the group to turn to the page indicated by their questioner, I expect the group to do their best to offer insight into the question, and I expect everyone to ask at least one question. For my 3-4 person groups, I allow 5 minutes for this activity. Then, we do Q and A as a whole class, stopping to take notes along the way as necessary. There are usually 2-3 passages I want to dig into briefly during this whole class time; if the students don't take our discussion there, I will. I randomly call on students for questions, and I take volunteers.

- Provide 20-30 minutes for reading in class: Homework completion is a major problem in my school; to get high percentages of my students reading the book, I provide time for them in class. However, it's not wasted time for me, as you'll see below. This is time in class is one of the key reasons my percentages are increasing.

- Page checks during the reading time: Once I release my students to read on their own for the day, I go around with my clipboard and note what page they're on. A core value in our class is that life is fair, and those who “fake it” eventually get pwned. Because of this, most of my students won't fake their page. If I do get a sense that a student is doing this, I'll pull them for a quick conference and ask some questions.

- Chart the class reading percentage: Based on the data I collect from reading checks, page checks, and conferences, I note on my clipboard who has read and who hasn't (and who shouldn't be counted today because of an absence). I then calculate our reading percentage and write it on the board (as shown above); if we're above 70%, I use green; if we're below, I use red.

- Offer audio: I haven't tried this, but my colleague Erica Beaton had success with offering students an audio option through their netbooks when they read Great Gatsby in 10th grade. If you'd like to ask her about it, hit her up in the Twittersphere.

- Parent contact: My students are now used to the fact that, if they do not complete homework, their parents could be receiving a concerned phone call or email from me. This, like all the others on this list, isn't a bulletproof solution for every kid, but it is very powerful for some.

- “Motivational speeches”: One day after school Erica came into my room and saw that our reading percentages were increasing; she asked, “What'd you do?” A student was in the room doing some make-up work, and the student said: “He gives us motivational speeches.” I'm not sure what exactly she meant, but I do repeatedly try to communicate the following to my students:

- “If you were mediocre, I'd expect mediocrity; since I happened to get a group of exceptional students, I expect exceptional percentages.”

- “Our society expects few of you to read stuff that's difficult or (gasp) boring; you all should be angry about such low, condescending expectations.”

- “I am thankful for my ability to grit through difficult reading for the eventual payoff of a good discussion, a powerful moment, or simply the growth that comes from practicing grit; reading is a chance for you to develop the ‘delayed gratification' muscle that all successful people tend to have.”

- “More than anything, I want you to have choices in life; for many of you, that means you need to make drastic gains in reading and grit. If you give 110% in your reading of this book, you'll grow in both reading and grit.”

What's a typical lesson look like?

So here's what a typical 70-minute class period looks like when we're reading a whole-class, extended text:

- Grammar warm-up (5 min)

- Reading check (2 min) — here's the list of reading checks I used for All Quiet on the Western Front

- Q&A/Discussion with note-taking (table groups, then whole class) (20 min)

- Reading assignment (35 min)

- Once we're into the book, I try to assign slightly fewer pages than minutes I provide in class; this means most students will have 5-10 minutes of homework.

- While students are reading, I am calculating our class reading percentage for the day using the reading check results, recording student page numbers, and conferring with students as I see fit.

- When I confer with students, I either ask them to come into the hall or I speak with them at their desk. I make this decision based on privacy needs and how hard I plan to push.

- Closing Q&A (5 min)

The choice reading + shorter complex texts approach

Some would argue that the best way to accomplish the Common Core text complexity shift is by using shorter complex texts that can be closely read in a single sitting so that most of the extended text reading is student-chosen and, with the proper coaching, increasingly complex. Penny Kittle is an advocate of this approach.

While I do use choice reading (most heavily in the first trimester), I don't choose to go “all in” on it. When I asked Penny for her reasoning in doing so, she honestly answered that she tries to weigh out what is gained and what is lost. I couldn't agree with her more in that kind of thinking; there is no “silver bullet” in education. In Penny's experience, more is gained by providing greater choice and coaching students in conferences to make choices that will push them; in mine, more is gained by providing whole class extended complex texts. I find that my approach enables me to push the most kids to do the most growing; she finds that her approach does the same. Does my way fail for some kids? Yes. Does hers? Yes.

I respect Penny Kittle and appreciate the fact that she is experimenting with a workshop approach in a high school setting. I also appreciate the fact that she is on a curling team.

What about in history?

Finally, let's discuss my developing approach for using complex texts in the world history classroom. I am in my second year as a history teacher, so this is still developing.

My goal as a world history teacher is to build a fence in my student's brains. The fence itself represents a chronological framework of world history; the fenceposts represent deeper learning experiences (e.g., digging into some source documents or articles; simulating socialism and capitalism; reading Escape from Camp 14 or Julius Caesar).

To build the fence, we depend primarily on the Student's Friend textbook, John Green's Crash Course: World History videos, and interactive lectures (which Schmoker describes in Focus). To dig the postholes, we depend mostly on the article of the week and extended complex texts.

My approach in World History: shared complex texts of varying lengths

Here are the complex texts that my 9th grade students read, discuss, write about, and debate in world history:

- Trimester 1: ~20 articles and source documents; excerpts from Student's Friend textbook; Shakespeare's Julius Caesar

- Trimester 2: ~20 articles and source docs; excerpts from Student's Friend textbook; Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (I'd like to add this for next year)

- Trimester 3: ~20 articles and source docs; Students Friend textbook; Harden's Escape from Camp 14

In the next post, I examine close reading (which is heavily featured in R.CCR.1) and how it can create a thriving classroom of readers, writers, and thinkers.

Erica Beaton says

D-Man, Yes! I have so many big things I want to say in response to this post. I’ll just start with a colloquial SQUEE, if that’s okay, and then come back and drop my two-cents as I come to more genius revelations, you know, like I normally do when I pop in your classroom. 😉

#1: Knowing that your ninth grade rock stars move on to tenth grade with me, I was feeling that I personally needed to revisit Animal Farm before we approach the Cold War. I wanted to build on what you did last year, but I wasn’t feeling so confident about who represented who.

So this week, I listened to the free audio on YouTube. This link <> has such quality narration! I love it! And to say that I loved Orwell is kind of a lot for me. The bleating sheep’s “Four legs good. Two legs baaaad” is fantastic.

I know that our students don’t have access to YouTube at school, but we could certainly find this version at the public library. This is just a thought, if you want to open this option to students in class.

davestuartjr says

E-money, thank you for this comment and for the sqee-ing. I will look forward to the usual genius revs 🙂

Your link got jacked up — that audio sounds really good though! I would like to offer audio for some of my strugglers. I will do a little snooping online; maybe there is some audio hosted via a non-filtered site (e.g., teachertube).

Thank you E! I will be interested to hear what your students have retained from Animal Farm. As always, our work with that book last year was woefully inadequate, thanks to me being a total noob.

Erica Beaton says

Shawn says

Dave,

First off, let me say thank you for your blog! I came across this in my research and find my teaching philosophies aligned with many of your practices. I’m actually an 8th grade English teacher in the Toledo area and am in my second year of teaching. I’ve incorporated many of Kelly Gallagher’s ideas into my teaching as well. What one thing that I’ve really struggled with this year is how to best spend my fatuous 90 min that I get with my kids daily. I’m trying to incorporate independent reading, reading instruction, and daily writing into each day. I guess my question is how do you approach your time? I recently picked up a copy of Focus via your recommendation and it seems he has an almost oversimplified approach to this. I’m also curious if you do any kind of daily writing or how you incorporate a writing curriculum in your class?

davestuartjr says

Shawn, thanks so much for your encouraging comment and your pursuit of the burning questions. My approach to my time transitions as the year progresses. In the first trimester of school, I’m having students spend ~20 minutes choice reading during my 70 minute periods. The remaining time is spent reading, writing, discussing, and debating articles and some shorter pieces (e.g. short stories, a Shakespearean play, excerpts from the Odyssey).

During 2nd trimester, I’m transitioning to some longer shared works, but largely having my students read them in class, still with a lot of scaffolding from me. Romeo and Juliet is read in class, and Separate Peace and Things Fall Apart are assigned with increasing (yet still tiny) amounts sent home. During this trimester, there are intermittent periods of choice reading (especially when assigned reading isn’t being sent home).

During 3rd trimester, the independent, non-choice reading is intensified, and in-class choice reading all but disappears (however, some students maintain the habit in spare moments and at home). We read Animal Farm, Things Fall Apart, All Quiet on the Western Front, and Fahrenheit 451.

To get back to your “use of time” question, the reason I enjoy Schmoker’s approach (and I totally agree — it’s oversimplified) is because I know that if I’m operating somewhere within that authentic literacy model he talks about, my students are getting great mental workout. My goal is just to keep it moving between reading, writing, discussing, debating. Within those, I experiment with forms, ways of grading, etc.

So, in the end, my class generally looks like this:

–20 minutes of reading every day, minimum — choice-driven during the first half of the year, teacher-chosen during the latter half.

–50 minutes of reading, writing, discussing, debating, all of which shift between direct instruction, guided practice, collaboration, and independent practice (our district is big on the gradual release model).

Shawn, seriously, thank you so much for your message. I haven’t even met you, yet I already respect you for the hard work you’re doing. You’re light years ahead of where I was as a 2nd year teacher; in fact, I’d wager your ahead of me now!

Cheers.

Mary says

I think I missed this one while recovering from jet lag. I think this is going to be my go-to post for teachers who say the Common Core will be too restrictive for their teaching style, or too rigorous for their students, etc. You truly are highlighting the best ways of teaching the core, Dave! Will there be a book someday with all your great teaching advice?

davestuartjr says

Mary, if you can find me an agent and/or a publisher, sure there will be 😉 Thanks so much for your encouragement and support, Mary. It spurs me on!

Denise Ahlquist says

Thanks for the great post and the fantastic hard work you are putting in with your students! Spreading the word that it can be done and the practical craft tips on how to do it is so encouraging. Keep it up Dave and everyone who knows you DO make a difference every day!

davestuartjr says

Denise, I so appreciate your encouragement, and I’d like to add three cheers for the Internet’s 20th birthday this week. I hope that we can work together through this blog and others to spread the message that the sky doesn’t have to be falling simply because the Common Core exist.

Shawn says

Hey Dave,

I adopted your model here with our Holocaust unit as we read Night by Elie Wiesel. I think it has worked very well! Each day the kids begin class by getting into their discussion groups (differentiated with a student from each reading tier: high, mid, low). They each take turns sharing the one question they came up with from the reading and take notes on their group members’ responses. I then have a few students share they question with the class as we all turn to the correlating page. I also have them add a question of my own to their list and have them answer it in their groups. We’ve only done photocopies of one page with annotating but it went well too! Then they go off and read the next section, sometimes with me reading the first few pages aloud.

My question now is, what do you usually do for your summative assessment of the novel? I’m considering doing a two day assessment:

Day 1: Comprehension multiple choice test (maybe 30-40 questions). My thought was that this would assess that Common Core Standard of comprehending complex texts. Plus, it would allow me to see which students really understood the novel from their discussions,

Day 2: In-class essay. I was thinking of giving them the essay topics (3-4) a day before. In class, they pick one of the essay questions and they have to outline and write a well-developed essay in one period (40 minutes).

With whole-class novels in the past, I have always done a short answer test (1 day, 10 or so questions of a paragraph or less).

I’d love to hear your thoughts and recommendations and experience! Thanks for all you do for this profession!

davestuartjr says

Hi Shawn,

First of all, congrats on developing what sounds like a really promising application of authentic literacy. You are giving your students a chance to read and discuss an extended complex text. I’m also glad to hear that the annotating went well.

For summative assessment in a novel-based unit, I tend to go with an in-class, argumentative essay. For my 9th graders, I expect to see arguments supported with textual evidence (from their notes throughout the book), and I expect them to fairly deal with at least one counterclaim. Because these requirements complicate things a bit, I give some planning time (~20 minutes) prior to the test.

In terms of testing comprehension of complex texts (I think the standard you are referring to here is R.CCR.1 — sorry to go nerd on you), I think the best way to do that is to give them a photocopied page or two and then ask them questions based on it. But my worry with giving them a 30-40 question MC test over the book would be 1) you’d spend so much time making the test, and 2) they could simply learn the book through in-class discussions or Sparknotes rather than actually reading and comprehending Night.

To get around these problems but to still assess whether students have comprehended what they’ve read, I take a given passage that they students have been assigned to read, and I pick one of the biggest, most overarching events or discussions that take place. I try to pick something that, if you didn’t get it, you’re either really struggling with comprehension or you didn’t read. I then ask that question at the start of class, and students turn in their answers on a small slip of paper.

I take these mini-quizzes and add the points up for a cumulative grade at the end of the unit. The resulting score isn’t a perfectly clear picture yet, but it does give me a talking point when I confer with students to gain greater clarity on how they’re doing.

Well Shawn, my apologies for the long-windedness. Do take care, and, as always, I love hearing your questions and triumphs!

Cheers,

Dave

Cynthia French says

I found your blog today and love it! I am writing 11th grade CCSS curriculum for my district in LI, NY. I love your no freak out approach and have lowered my blood pressure a few points since reading your posts. That being said, I just wanted to add something I tell my students regarding sharing test questions with the afternoon classes. I ask them, “if you worked in a restaurant, earned the same wages as the other servers, and were competing with them for a higher ranking position, would you do their side work to make their day easier?” The obvious answer is no. In addition, regarding copying HW, I give them generic lines to feed would be copiers such as, “it’s in my locker, I don’t have it with me, etc.” Lastly, regarding reading check quizzes, lets face it, if you read carefully, fully, and closely, it’s a near guaranteed 100/A. Knowing you will have a RCQ and NOT reading is like walking past a 100 dollar bill because you didn’t take the time to bend and pick it up. Class rank matters and giving away answers is self-sabotaging.

Thanks for a great blog!

davestuartjr says

Cynthia, thanks for the enthusiastic endorsement and the awesome ideas! I love your illustrations to help students understand the reasons against cheating the system. I also like that you acknowledge the fact that, sometimes, students simply don’t know what to say when someone comes up to them asking to copy homework. You equip them with specific lines; that is awesome.

Please keep the commentary up, Cynthia — you’ve got some valuable ideas to benefit the community with!

Hillary King says

Hi Dave,

I have so much to say regarding your fabulous website, but I don’t have time to write it all because I am so entranced with devouring more and more pages of your ideas and the links to other resources. It’s so helpful to have targeted and trusted resources!! I was thinking the same thing as Shawn. I teach 8th grade and we have a weird schedule. 3 days a week we have 50 min periods and 2 days are blocks. We have a built in SSR every day so I don’t need to allocate reading as often in class. My questions are these:

1. If I try to do an in-class essay test, is there any problem in allowing them to start one day and finish another day? Wouldn’t it be ok to encourage them to do more reading, review, and actually improve?

2. In 8th grade, we have to teach a LOT of new content and skills, so do you have suggestions as to how to front load and teach those with articles of the week AND literature during earlier units without boring the kids too much? Would teaching literary devices and terms conflict too much with articles of the week?

I will have many more questions in the future. I’m about to start my 3rd year of teaching and absolutely love improving my practice. I want to help grow critical thinkers who are thoughtful and good citizens of the world. Thanks for inspiring and helping me improve. The CCSS are the bomb.com.

davestuartjr says

Hi Hilary,

Thank you, first of all, for being so generous with your encouragement. You are my kind of person.

1. I usually allow my students to bring notes and any other preparation for the essay (and they know the essay question in advance and have usually debated on it), so you’d essentially be doing the same thing. I don’t see a problem with it — the point of the essays isn’t to quiz them or “get” them, it’s to see their thinking and how well they can communicate it in writing. In other words, ‘Yes’ to your second question.

2. Basically, I’d use AoWs as a method for giving kids more chances to read more texts, developing their background knowledge, their reading stamina, and their skill as readers of informational or argumentative texts. I treat literary terms separately, in the context of our literature units.

Seriously Hilary — you rock. Keep the questions and comments coming 🙂

Yours,

Dave

Erica Beaton says

Thank you, Shawn! I took your advice this morning and did just the same procedure with To Kill a Mockingbird. The second-draft close read worked really well to narrow their focus and dig deeper, asking questions and connecting to theme. Thanks again!

Nicole L. Mancini says

I like the idea of the “mini-quizzes” you mentioned above! Do you have multiple periods of the same class though? I’ve had issues with kids in a morning class sharing questions with those who have it after lunch. How do you get around that?

davestuartjr says

Hey Nicole! I do change up the question for that exact reason. On average, I probably do this at least once per every three mini-quizzes. Basically, if I can think of another good one, I use it; if I can’t, I don’t. The trick I aim for is to get the kids realizing that relying on answers from an earlier class isn’t a great strategy.

But nearly every day the kids will hear from me some variation of the theme that there’s almost always a way to sneak past a requirement — the question is, what are the consequences? I want them to think way bigger than grades–I want them to think about the brain workout and habit-building they get from grappling with the reading.

So those are my semi-organized thoughts on that, Nicole — thanks for reaching out!

Michael says

All very interesting…except your premise of ‘complex text’. AQWF reps an 830 Lexile- below what CC asks for 9th graders. I like everything else though, and as Dept. Chair, I will be linking your blog to our online forum…Kudos to you for giving your all.

davestuartjr says

Hi Michael,

I appreciate the kind words! I do want to clear up a little confusion, though — Lexile is only one of three elements that the CCSS use to measure text complexity. The good news with this is that the CCSS has a much more nuance, accurate view of a text’s difficulty–after all, there is more to the difficulty of a text than what an algorithm like Lexile can measure. But the bad news is that determining a text’s complexity becomes more complicated than a trip to Lexile.com. According to CCSS, we also need to take into account qualitative measures (like levels of meaning and language conventionality) AND reader/task measures (like how closely we’ll require students to read the text or how much background knowledge students have with the text).

So in the case of AQWF, the Lexile (which takes into account things like sentence length and word length/frequency) may be below a 9th grade level, but qualitatively it is complex (e.g., Remarque uses language that, to a contemporary student, is unconventional) and it’s also complex for my particular readers (e.g., they have little to no background knowledge, when we begin the novel, of WWI, German culture/history, and so on).

I hope that makes sense because what you’re saying is a legitimate thought and it’s one thing publishers aren’t doing a great job explaining, from what I’ve seen. For more info, check out this post: What’s the Big Deal about Text Complexity?