[Update from Dave: my all-day literacy workshop for 6-12 teachers across the content areas includes a solid segment on getting kids speaking and listening in a way that increases their long-term success and improves their mastery of content. Read more about that workshop here. I'd love to come to your school.]

Prior to the Common Core, I nurtured a belief that not all of my students needed to talk. After all, some are shy (I was, too, as a secondary school student), and mandatory speaking events can bring about fits of visceral terror for the introverted.

But since then, my thinking has changed significantly.

My first cognitive shift came during a field trip to a Amway, a global corporation based in nearby Grand Rapids, MI. On our field trip, Amway employees from a diverse array of jobs conducted career round tables with our students. As I walked around and eavesdropped and, later in the day, listened to the keynote speaker from the Human Resources department, one skill repeatedly stole the show: the simple ability to communicate with people in person for a variety of purposes and in a variety of settings (essentially, SL.CCR.1).

It's not sexy, and, like Thomas Newkirk has accurately stated, “Standardized tests are ill-suited to evaluate” it. And yet, speaking is critical for just about any job that requires you to wear pants (and probably many that don't).

Another shift occurred when I began reading the work of Schmoker and Graff, and, starting last summer, the Common Core standards themselves. They all seemed to suggest that simply getting every student reading, writing, and talking would do much to prepare students for a diverse array of post-secondary demands. And so it came to be that I grew convinced enough to implement three simple strategies for ensuring every student spoke just about every day. I have been honing them ever since.

1. Index cards

At the beginning of my courses, I have each student write their name on an index card. (I might ask for other information that will help me learn about them, too.)

At the beginning of my courses, I have each student write their name on an index card. (I might ask for other information that will help me learn about them, too.)

Once I collect the index cards, I now have one of the single most effective tools for participation known to humanity. (It should also be noted that the index cards are slightly less expensive than a Smartboard.)

Whenever it's time to call on students to share their thinking on an issue, a text, or a question I've posed, I use the index cards. If I can work through a deck each class period, I have ensured that every student has spoken at least once.

But how do we give those shy students a chance to rehearse what they might say when called upon? To achieve that, I use another outrageously sexy and newfangled technique called think-pair-share.

2. Think-pair-share

This decades old strategy goes back to Frank Lyman. I feel somewhat idiotic for explaining it, but then again, I managed to get a Bachelor's in Education without actually learning that this is a legit strategy. Honestly, this has become the archetype for 90% of the small group collaboration that happens in my room.

- Think = students think about the question I've posed or write about it.

- Pair = students discuss in pairs (or, in my class, in triads/quads).

- Share = students are randomly called on to share the fruit of their discussions.

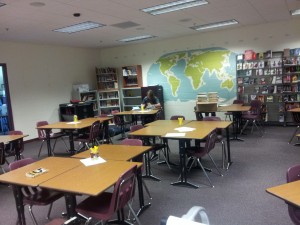

First of all, my desks are arranged in triads and quads. Most are triads, and the quads are there in case I've got odd numbers or extra kiddos. At numerous points in any given lesson, I get all my students talking by asking them a provocative or text-based question, and then saying, “Discuss in your groups.”

First of all, my desks are arranged in triads and quads. Most are triads, and the quads are there in case I've got odd numbers or extra kiddos. At numerous points in any given lesson, I get all my students talking by asking them a provocative or text-based question, and then saying, “Discuss in your groups.”

The procedure that I teach heavily at the start of the year is simple:

- Everyone is to participate when I say “discuss in your groups.”

- If I teach a discussion move (e.g., paraphrasing) before the activity, use it.

- If someone is inaudible, the other group members are to simply say, “Louder please.”

- After I end the discussion period (which ranges from 1-3 minutes), everyone in the group is responsible for being able to summarize everything that was said during the discussion.

What do I do when this doesn't work?

- I reteach the what-why-how for think-pair-shares:

- WHAT: I remind them what it is.

- WHY: I hit on either college/career-readiness (e.g., telling the story about the Amway field trip) or character strengths (to do think-pair-share well, students need grit, curiosity, optimism, and self-control).

- HOW: I explicitly go through the procedure with the class, demonstrating what exactly it looks like to have a quick, collegiate discussion in their triads/quads. I sometimes have a group of students model it step by step.

- (Although this reteaching seems a bit extreme, it works every time. I think that, over time, even the best strategies can become diluted, and reteaching the what-why-how helps.)

- I will sometimes simply grade those who I randomly call on — this is as simple as giving them a point if they have something to contribute and can recall their group's discussion, and not giving them a point if they say “I don't know” or something similarly unimpressive.

- If I'm noticing that discussions are becoming dominated by certain individuals, I might say, “For this discussion, the person closest the window gets to start.”

3. Mandatory participation in debates and discussions

Several times per unit, we either circle up the desks and have a discussion about texts we've been reading, or we hold a debate. I outline a lot of what these debates entail in Part 4 of this series, but here I want to touch on my thinking in terms of requiring every student to speak in these speaking/listening events.

Opponents of requiring all students to speak would likely say (and I would respond):

- Not everyone will need to speak to groups of 30 people in their adult lives, so why force everyone to practice it in school?

- My goal isn't to create classes of public speakers, but it is to enable my students to live choice-filled lives. If they choose to pursue professions that require no public speaking, great! But I want them to have a choice, and even for those who pick the most introverted jobs in the world (e.g., like flying to and from Mars), having some experience with some level of public speaking won't hurt them.

- Speaking to a whole class is nerve-wracking, especially for introverted students; in some cases, the level of anxiety created can actually make students sick (Rebekah, one of my students this year, actually had tears in her eyes during an early speaking/listening event).

- A fair percentage of students do start the year in my class with varying levels of anxiety around whole-class speaking/listening events. However, practically all of them become quite comfortable by mid-year, and some, like Rebekah, find that public speaking is a passion (Rebekah wants to pursue a career in public affairs).

- There's no way the SBAC/PARCC tests will be able to assess speaking/listening, so why spend time on it?

- (Insert stream of barely contained expletives.) I understand that some states/districts/schools are doing the solid, reductionistic work of reducing teacher effectiveness.

What about kids who refuse to speak?

In the myriad whole-class speaking/listening opportunities I've provided for my students, I have experienced only one or two instances of non-cooperation. The rate of non-cooperation has been far less than 1%. Here's why I think that's the case:

- I begin the year with argument, and this helps students immediately grasp that argument can be fun.

- Mandatory, graded whole-class speaking/listening opportunities always have some level of prep/rehearsal time (“think” and “pair” modes).

- I am vigilant in creating a safe space for my students. Meanness is out of place and unacceptable. My students know they won't be mocked for not having it all together.

- I model the value of failure. My students know that those who deliberately practice in their areas of weakness have a huge advantage over those who don't. They know that I am the most expert failer in the room because I've failed the most and I aggressively learn from failure.

- I share motivational stories of people who have had to speak in public to get to their goals.

- I share that I was the shy kid in high school, and I wish someone would have forced me to talk more.

- Grading helps.

- Peer pressure helps — 99% of students participate.

- And finally, I never make a big deal out of non-participation. I simply mark it on my clipboard and move on. Afterwards, I try to connect with students on why they didn't participate, but even if I don't get a chance to do that, they've usually learned whatever lesson they needed to learn that day — to prepare better, to just go for it next time, or whatever.

Get after it

If you're nervous about requiring participation in whole-class speaking/listening events, I totally understand — I, as a former shy kid, was nervous, too. Yet, as I look at my students and how they've grown in confidence and skill, I'm thankful I dared to expect every one of them to participate in each of our speaking/listening events.

franmcveighFran says

Dave,

I love how you talk about the “teacher’s responsibilities.” “What do I do when this doesn’t work?

I reteach the what-why-how for think-pair-shares. . . ”

It is so critical that the teacher use that “formative ” data to “reteach” until the students are successful.The “what-why-how” part is the routine that will help most students become successful.

You have nailed speaking and listening so well. And you are right! Technology was not required! (However it is nice to capture the growth from early to late in the year and listen to students explain what they have learned!