About a year and a half ago, I came up with the non-freaked out approach to Common Core literacy while driving home from a conference for edu-policy types in my state capital of Lansing. I was frustrated by the acrimony that seemed to suffuse the day's sessions — there were politicians bickering with superintendents bickering with teachers bickering with unions bickering with community members, on everything from early childhood educational access to online schooling.

Don't get me wrong — there are a lot of problems in education today, and I want them solved just as much as the next person who loves children and their long-term flourishing. The thing is, nothing was getting solved at this thing.

So I was driving home and thinking about all this, and that's when it hit me that the one thing I needed to do with my little blog is promote the idea that we don't need to freak out about the Common Core, and that, in fact, we're wasting a lot of energy doing so. On the contrary, I saw that we needed to become students of the standards, learning what they actually say and then doing the critical work of reducing them. In short, we needed to own the standards and figure out which were most important, thus enabling us and our students to become experts at a few critical things rather than mediocre at every last sub-skill.

When I got to a computer, I took a crack at it — I drafted what I, after reading through, implementing, and researching the standards, considered the most important things to focus on. I wrote a post on this “non-freaked out approach,” and then wrote posts on each of the six elements I thought were most crucial:

- Vastly increase the amount of grade-level complex texts that students are reading

- Teach the whole class how to closely read grade-level complex texts

- Go big on argument

- Ensure that every student speaks every day

- Write like crazy

- Teach grit and self-control

(Later on in this article, I start referring to the above list as NFO Approach 1.0.)

It's time for 2.0

My students and I have implemented and experimented and loved the heck out of those six, high-bang-for-your-buck elements of what I feel is not just an effective model for implementing the Common Core literacy standards, but simply for building literate, life-dominating students in general. These are the kinds of practices I hope my own children are immersed in during their schooling; these are things every teacher (even average ones like myself) can master instructionally; I believe in these, big time.

But here's the thing: they need honing.

So, without further ado, let me show you what I've been tinkering with for the past few months and what I've started talking to teachers about when I speak about non-freaked out literacy.

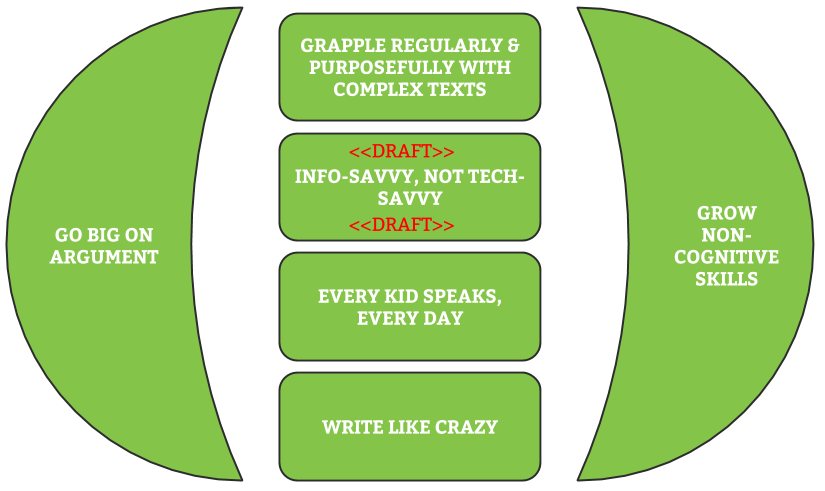

Let me explain the thinking this image represents.

Not all elements of the non-freaked out approach are equal

There are two elements, in particular — go big on argument and grow non-cognitive skills — that have an all-encompassing nature in my classroom, both instructionally and culturally.

Argument, as Jerry Graff and Cathy Birkenstein-Graff explain masterfully in “An Immodest Proposal for Connecting High School and College,” is the name of the game in academia. Therefore, the first step to helping more students understand and grow comfortable in academic settings is creating secondary classrooms in which argument is a mega-theme throughout the course. For this reason, the image above depicts argument as a large, cupping thing — it is one side of what cups in the reading, research, speaking/listening, and writing work we want students to engage in.

In the first iteration of the non-freaked out approach, I advocated for simply teaching students grit and self-control. I don't regret that — of all of the non-cognitive skills being studied today, grit and self-control continue to be the most predictive of positive life outcomes — but I think I was boiling things down too far. As I've written elsewhere, the KIPP list of character strengths that I've adopted in my classroom contains a more well-rounded list, and as I haven't written elsewhere, things like Carol Dweck's growth mindset and David Conley's “key learning skills and techniques” deserve a seat at the table in any classroom seeking to help kids grow not just cognitive, tested abilities, but non-cognitive abilities as well.

So when I talk about and write about the non-freaked out approach in the future, I hope the visual “cupping hand thingies” of both argument and non-cognitive skills will help readers and listeners internalize the fact that these two things hold the other elements together, giving them much of their purpose and power.

The point of the non-freaked out approach is one thing: long-term student flourishing

Before I get into my thinking around the four elements in the middle of the non-freaked out (NFO) approach, it's worth emphasizing that the single, driving goal of everything I do as a teacher is to promote the long-term flourishing of my students. With every single one of the instructional minutes I'm given, I pray the strategies, assignments, and lessons I use do that one thing. That's it. That is my whole teaching philosophy.

This is one of the big reasons I initially appreciated the Common Core — before the document even begins discussing standards, it explains that the Common Core have one goal in mind: college and career readiness. For that reason, I'm sad to see so many people freaking out about what the Common Core authors say or how corporate interests are behind the standards or why the Common Core is actually an overt attempt by the federal government to wrest schooling away from state and local control.

All these things could or could not be true, but here's the thing: they do not matter a damn to the kids who will walk into my class this September. These kids come to me expecting one thing: to be prepared for life when they walk across the graduation stage.

So let's just be totally clear on that — I'm all about long-term student flourishing. That's my job. That's the job of schools. I'm not saying we can guarantee all kids will flourish in the long-term, but I am saying it's our job to do what we can to help them toward that end.

Close reading had to go

One of the seemingly largest but in actuality smallest changes in my latest thinking around NFO Approach 2.0 is that close reading doesn't get its own category. For one thing, close reading died (didn't you read the obituary?); for another, reading a text closely is just something we do in our attempts to grapple with what a complex text is saying and why that matters. From now on, when I speak or write about “close reading,” it will be as a part of helping kids deal with text complexity.

Also, it was important to get the word “purposefully” in an approach to complex texts. It should probably go without saying, but when it comes to assigning texts and teaching kids how to read them, we need to always be answering and re-answering questions like:

- Why this text?

- Why is it the right challenge for these kids?

- What authentic literacy practices will kids do with this text?

In short, we've got to be purposeful — we can't just chuck texts at kids.

Research needed a seat at the table

During this past school year, I worked with Jossey-Bass Wiley to flesh out the Non-Freaked Out Overview of the Common Core Anchor Standards ebook that I used to sell for $1+ on Teaching the Core. That resulted is my first big-kid book, which is set to release sometime around the beginning of this coming school year.

But even more importantly for you, dear reader, is that other things resulted, such as a nervous awareness that leaving research out of NFO Approach 1.0 wasn't good.

Consider the thick thread of anchors that deal with research-related skills:

- R.CCR.7: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

- R.CCR.8: Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

- R.CCR.9: Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

- W.CCR.7: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

- W.CCR.8: Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism.

- W.CCR.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- SL.CCR.4: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning, and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

- SL.CCR.5: Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

My friends, that is what we call “a lot of standards.”

Thus, you see in the graphic above my tentative language for the one brand-new element of NFO 2.0: info-savvy, not tech-savvy. Somehow I want to get better at teaching kids that being tech-savvy is pointless if you can't sophisticatedly navigate the insane amount of information on the Internet and then do something with that information.

Check out this link for a bit more thinking (not mine) on info-savviness — and here's an abstract of a study comparing tech-savviness with info-savviness.

What do you think?

In my head I had thought I'd share this with you all at the end of the summer when I had it all thought out and finalized. Thankfully, I realized that would be out of keeping with how we roll here at Teaching the Core. So there you go — this post has given you access to the frightening space known as my brain. What questions or comments do you have? What would you like me to keep in mind as I continue to develop my thinking this summer?

Matt Copeland says

Dave, I really like the graphic! I’m wondering if the words “and purposefully” might replace the word “not” in “info-savvy, not tech-savvy.” I think “tech-savviness” is important but only as a means to a greater end and not as an end itself.

Am intrigued by the non-cognitive skills as well. I’m wondering if you might be able to tie-in the “portraits” expressed on page 7 of the standards document? The math side of the house has the mathematical practices and I’ve argued that the ELA and literacy standards need something like this to serve as the “glue” to hold everything together.

Really appreciate the thought and energy you’ve put into this!

davestuartjr says

Matt, I’m not totally satisfied with that “info-savvy not tech-savvy” language either. You put it cogently: “Tech-savviness is important but only as a means to a greater end and not as an end itself.”

You are totally right — CCSS Lit standards could benefit from a “literacy practices” element. Maybe that’s what the portraits page is hinting at? This is all new thinking to me — thanks for getting my gears turning…

Matt Copeland says

Interesting proposition, isn’t it? I’m not convinced the “Portraits” completely capture the idea but I think it is a start. At one point, I boiled the portraits down to the “4 C’s:” comprehend, critique, construct, and communicate. But there is a lot missing there too, social learning, metacognition, all those “soft skills,” etc.

I feel if someone could clearly articulate those underpinnings it would serve as a solid foundation to advance instruction and probably make implementation of CCSS a little easier on all of us.

davestuartjr says

I’ll certainly be playing around with it, Matt — and I encourage you too as well; it’s awesome to see what different minds come up with (e.g., your ” 4 C’s” — I never would have thought of those).

When I speak/workshop on non-cognitive skills, I talk about:

–growth mindset

–character strengths (a la KIPP)

–Conley’s “key learning skills and techniques”

Stay tuned for more posts on these topics this summer.

Greg Schreur says

Thanks for not waiting until the end of the summer for those of us who want to reflect over the course of the summer and not cram in a year’s worth of prep into two days of PD.

Still not sure about “burying” close reading, but I do need to get students thinking more about what makes a text complex. I’ve recently been thinking about how grammar (and understanding language structures) can help students–and even how it helps me–with challenging reads.

davestuartjr says

I think kids still have to read closely — no question. I just need to get away from emphasizing that as a whole separate thing. It’s a part of grappling with complex texts — just as analyzing language structures is (which I’d love to hear more about).

Matt Copeland says

There was an interesting paper presented last week on syntactic complexity and how it seems erroneously missing from the text complexity triangle. I’d be happy to share it. Dave, can you email me?

Greg Schreur says

Good point. Besides, what is the opposite of close reading? Reading is reading, just at varying levels of intensity and focus. And, I would add, it’s not only about text complexity but also significance: teaching students to understand that not all words have equal value and when to read more closely, uh, carefully.

franmcveigh says

Your new thinking is very interesting and also very pertinent to the ever-changing focus in education. Some are often appalled that the target seems to move; yet if we are “learning” and “growing” should not our targets change?

Your focus: ” …an effective model for implementing the Common Core literacy standards, but simply for building literate, life-dominating students in general. These are the kinds of practices I hope my own children are immersed in during their schooling; these are things every teacher (even average ones like myself) can master instructionally; . . .” This is about the standards, teaching, and students! That focus is crucial.

I like the view of your graphic but I do have a few questions:

1) I wonder if the “time” elements: speaking every day, and grappling with complex text “regularly” will cause confusion? Is that just in ELA courses? Or is that across the day?

2) Is there a way to display the center list so they do not look the same size? So they do not look linear in fashion?

3) Where is “creating a love for reading”? Where is readers independently reading and understanding any text that they choose to read?

I humbly disagree that ELA needs process standards as our K-12 ELA standards include many processes already in the 10 reading, 10 writing, 6 speaking and listening and 6 language CCR Anchor Standards. Math needed K-12 process standards because those are their only standards that cover all grade levels.

I love your inclusion of Mindset as a source of your thinking. Dweck’s work is powerful. This work is complex and deserving of contemplation and discussion because students, their learning, and their future is at the heart of all our work!

Fran

davestuartjr says

Hi Fran,

You make some great points here and I particularly like the one about “creating a love for reading” because it’s been on my mind a lot lately (see my conversation with Penny Kittle over at this post).

Did you also notice that the NFO framework above has no element specifically tied to the Language standards? The vocabulary pieces (standards 4-6) can easily get woven into the reading, writing, and speaking elements of the NFO framework, and I guess the grammar/mechanics could get woven into those as well.

The key thing I’m learning about my work around this framework is that I want it to serve as a way for non-ELA teachers to engage with literacy development in a meaningful, powerful, but you-don’t-need-a-masters-in-literacy-instruction-theory manner.

All that is to say that no, this framework doesn’t include developing a love for reading, but I do see that as one of several key goals I have as a freshman composition and literature teacher each year, yet not as a primary goal in my history classes (there I might more broadly call it developing a love for learning). The framework also doesn’t deal with grammar/mechanics instruction, but that’s because, again, I see those skills as a key part of the curriculum in the abovementioned English course, but not in the history classes I teach.

Seriously great questions and insights, Fran — wow, I am indebted to you for how deeply and sincerely you engage here and elsewhere on the web. Would love to hear more questions or comments, any time, any where!

franmcveigh says

Thanks for your response, Dave!

I’ve been wondering if reading, writing, speaking and listening every day for every student needs to be an overlay of the whole graphic . . . . some reading, writing, speaking and listening should be in content areas as well as ELA but it wouldn’t have to be all of them every day.

I can’t imagine a single ELA class period without as least two of the three. I may be totally engrossed in my reading so today I either share in exit slip (writing) or 2 minute conversation(speaking and listening) with a peer during class. No data, but I believe that more purposeful use of all modalities could immediately begin to increase motivation (inference from SSR – improved effectiveness by adding “talking about reading” as ending component) and therefore enhance student learning. (Also, no huge $ commitment, but better use of our most precious commodity – TIME!)

Enjoy thinking with you!!!

Cyndy Chase says

How about “info savvy VS tech savvy? They both have a place and that way you can discuss each from their own perspective and, maybe, add a % comment to each?? Compare and contrast is always good. 🙂

kad4 says

I like that “non-cognitive” skills play a prominent role in your approach. I teach “Habits of Mind” because I like the sound of it. My list – which I think comes from the National Writing Project but I don’t remember for sure – Curiosity, Openness, Engagement, Creativity, Persistence, Responsibility, Flexibility, and Metacognition.

As far as info-savvy vs. tech-savvy issue…how about something like: Use appropriate technology to consume and produce information?? Never mind, that sounds weird. I am thinking that there are two sides of the information coin. First, they need to access, understand and synthesize information and second – they need to create informational content as well. “Synthesize, use, and create information”?

Okay, I have more thinking to do – thank you for getting the ideas going here!

Evangelyn Visser says

I think that “write like crazy” should reference that it is the result of thinking/communicating about the complex text students are grappling with. This will also pick up on all the text-based evidence that is woven into the standards.

Kyle Fedderly says

Good work – and great conversation!

If tech-savvy refers to the ways in which we share ideas (print, audio, video, etc.), info-savvy refers to the content of the ideas themselves. A key component of this (media?) literacy is the development of a critical curiosity for both an author’s intent and the methods he or she uses to accomplish his or her goals. That’s the nice version. Essentially, it is the cultivation of a healthy personal validity (conversely, B.S.) meter, by which the integrity of any piece of information can be judged. I like the way this promotes healthy argument in the classroom as students strive to communicate their beliefs (and reasons therefor) to their classmates. I further like the way this process subversively erodes the walls which insulate any particular viewpoint from honest self-reflection. I don’t know what that does for your graphic, but it might help define the field. I guess we’re talking about developing a critical awareness of purpose and technique behind (informational?) text.

Good luck!