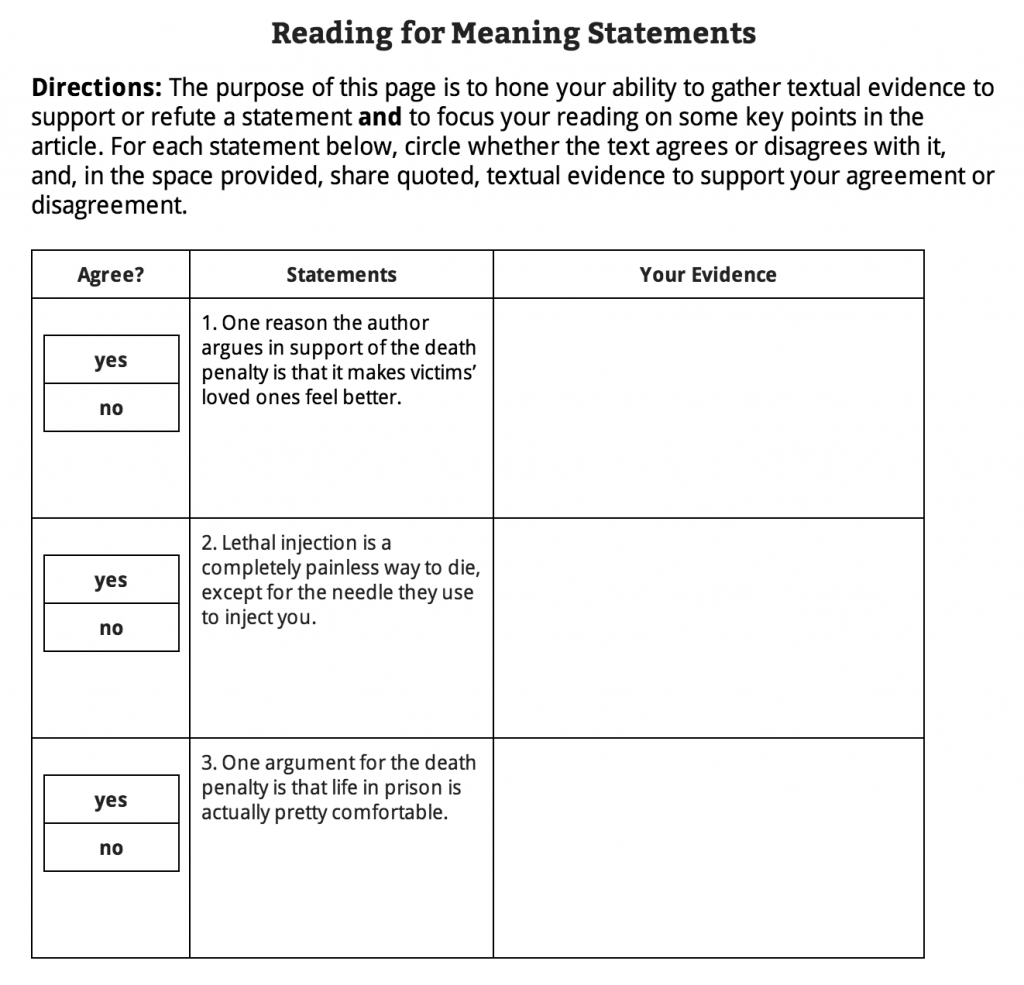

If you used any of the articles of the week I posted this year (just to be clear, Kelly Gallagher is the originator of the Article of the Week strategy), you definitely noticed some changes to the format. I've written elsewhere about why I use Graff/Birkenstein's They Say/I Say strategy with AoWs (here and here), but I haven't said much about the “Reading for Meaning” (RFM) statements I now include on many articles (see screen shot below).

In this post, I'll be explaining what's up with those.

Reading for Meaning, brought to me by The Core Six

I first learned of Reading for Meaning statements when I picked up a copy of Silver, Dewing, and Perini's The Core Six: Essential Strategies for Achieving Excellence with the Common Core. As the title implies, the book shares six research-based strategies teachers can use to help students grapple with the demands of the Common Core. For my curious readers, here are the six, along with a mini-synopsis of each (let me know if you'd appreciate a post on my experiences with strategies other than Reading for Meaning — also, pick up the book if these appeal to you):

I first learned of Reading for Meaning statements when I picked up a copy of Silver, Dewing, and Perini's The Core Six: Essential Strategies for Achieving Excellence with the Common Core. As the title implies, the book shares six research-based strategies teachers can use to help students grapple with the demands of the Common Core. For my curious readers, here are the six, along with a mini-synopsis of each (let me know if you'd appreciate a post on my experiences with strategies other than Reading for Meaning — also, pick up the book if these appeal to you):

- Reading for Meaning — gives practice in the basic skills readers use when grappling with complex texts.

- Compare & Contrast — “teaches students to conduct a thorough comparative analysis” (p. 3)

- Inductive Learning — “helps students find patterns and structures built into content through… analyzing specifics to form generalizations” (p. 3)

- Circle of Knowledge — “a strategic framework for planning and conducting classroom discussions that engage all students in deeper thinking and thoughtful communication” (p. 3)

- Write to Learn — “helps teachers integrate writing into daily instruction and develop students' writing skills in key text types associated with college and career readiness” (p. 3)

- Vocabulary's CODE — “a strategic approach to vocab instruction that improves students' ability to retain and use crucial vocab terms” (p. 3)

I implemented pieces of all of the above strategies during this past school year, so again, if you'd like further treatment of any of them by a layman, let me know in the comments, and if you'd prefer to hear it straight from the pros, grab the book.

How do I use the Reading for Meaning strategy, in 250 words or less?

- Pick a complex text.

- Create statement(s) about the text (see AoW screen capture above for a few examples).

- Important: Make sure the statements are supported or refuted by the text.

- Pro tips:

- Use Figure 1.2 on this page to create statements to address specific standards.

- Create thought-provoking statements, so as to engage student interest before reading.

- Before reading, have students preview the statements, and use this opportunity to include any other activity that might “hook” students into the reading. (E.g., I might use the efficient “take a stand” strategy to have them show me whether they agree or disagree with some element of controversy presented in the text.)

- Show students how to “record evidence for and against each statement while (or after) they read” (p. 10)

- After reading, students can discuss their evidence in pairs or small groups, seeking to reach an agreement on which statements are supported or refuted by the text. This can be extended to a whole-class discussion “in which students share and justify their positions” (p. 10), which provides the teacher with an opportunity to “help students clarify their thinking and call their attention to evidence they might have missed or misinterpreted” (p. 10).

- Use student responses, both in their recorded Reading for Meaning statements and in their discussions, as formative data in evaluating how well they understood the text.

RFM develops three moves readers do when grappling with text complexity

In my last post, I mentioned Harvard's “thinking-intensive reading”; to save you a click, below you'll find the outline of that framework:

- Previewing: Look “around” the text before you start reading.

- Annotating: Make your reading thinking-intensive from start to finish.

- Outline, summarize, analyze: Take the information apart, look at its parts, and then try to put it back together again in language that is meaningful to you.

- Look for repetitions and patterns.

- Contextualize: Take stock and put the text in perspective.

- Compare and Contrast: Set course readings against each other to determine their relationships (hidden or explicit).

Notice how this aligns with the three phases of the Reading for Meaning strategy:

- Previewing and predicting before reading (which lines up with the first bullet point above)

- Actively searching for relevant info during reading (which is involved in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th bullet points above)

- Reflecting on learning after reading (emphasized in the final two bullet points above)

In short, RFM can serve as a great scaffold for those shorter, complex texts you give your readers.

Scaffolding readers and helping teachers

If the Common Core simply results in teachers chucking complex texts at classes of kids without any support or instruction, then, indeed, the Common Core will have been something worth freaking out about. However, with simple, efficient strategies like Reading for Meaning, teachers can get closer to that sweet spot between under- and over-teaching, and students will end up with the win as more of them enter the college and career world as functionally literate folks.

Have you used RFM statements before? Do you have any further questions I can answer? Holler at your boy below.

Amy Kinseth says

This sounds great! I’m going to try to use this with my 4th graders next year. Thanks so much!

sarakershaw says

I like the idea of using the AoW time to hone different specific reading strategies that can translate to other areas. Thanks, Dave!

Ken says

Dave, I’ve been inhaling most of your posts, and they are extremely helpful! I have a few questions about the roll out of AOW–(yes, I did purchase your guide and it was awesome)…. here goes,

1. How early in the year do you start with AOW? First full week? I want to jump right in on this early on, but I want it set it up properly so that it’s a success.

2. I feel like there is a good amount of scaffolding that has to be done before AOW begins, right? Students have to know how to annotate, how to use the RFM statements (which you just described in this post), how to complete the 250 word reflection, be introduced to the rubric. I assume you do a lot of this work together with the students early on?

3. This year I’ll be teaching tenth grade in the Bronx, and I am wondering about the balance between choice reading and whole class novels. I’ve read a few of your posts about this (as well as Erica Beaton’s), and I guess I’m just wondering how are you able to tie in choice reading most days in your class? I am a believer in the reading workshop model, but I also am dying to teach Animal Farm and Night to my students….

Sorry to barrage you with questions, thank you so much for all the work you do here! I definitely think you should collect all your posts and write a book!

Michelle Roy says

Your post about The Core Six inspired me to buy the book this summer. I have implemented the some of the strategies so far this year (our school year begins in early August.) Reading for Meaning is my favorite; it allows me to scaffold and support reading on so many levels. I am sharing the 6 strategies over the next few weeks in my PLC group. Thanks for being my source of practical instructional strategies.

davestuartjr says

Michelle, that is so great to hear. I feel like there’s a pressure in teaching for us to create new activities and share these things no one’s ever done before, and that makes no sense to me. There are resources and strategies and research-based instructional approaches out there — why reinvent the wheel? Ain’t nobody got time…

So thank you, Michelle — let me know how your PLC responds!

linda says

noticed your RFM sheet and you highlighted the “5 arguments for and against the death penalty”. I was wondering if you have had any push back from parents or admin on the choice of this text since it’s a bit shocking with the description of the death process…snapping of the neck, etc. unwritten honor code amongst prisoners gangrape, etc. Also, I don’t know much about Listverse where it came from. /what is your justification for this choice of text for high schoolers,, Most of your AoW’s seem to be higher end publications, NYTimes, Atlantic Monthly. What was your reasoning behind this choice? It seems more like a blog? As a new teacher, don’t want to make a big mist’ep!

davestuartjr says

Hi Linda! I haven’t had any pushback, and I do briefly address with students the serious nature of what’s being described. It is definitely a blog-type source, much less authoritative than those other publications you list. I used the source because the death penalty was coming up in our world history class, and I wanted students to consider a variety of angles on the issue.

Feel free to comment back if I didn’t clear anything up — thank you, Linda, for your questions!

Angie Pfeifer says

I can see leaving this completely blank and having students individually or in groups determine implicit or explicit claims in the article. This way, you can further differentiate by having one blank sheet work for articles of their choice. This would be especially useful for gifted kids who could then pursue an area of passion. Also, it ups the ante a bit in that they have to determine important aspects in their reading on their own — eventually.