On the first day of school, I tell my students that one of the central threads of academia, and clear thinking in general, is argument.

Now: guess what pops into their heads when they hear that word?

Let's just put it this way — it's not exactly the image I want them leaving my class with on the first day of school. Toward beginning to give them a proper understanding of argumentation, then, and toward building the “Family and Team” culture I want for my classroom, here's how part of my first lesson will look.

(And in case you're wondering, “Wait — is argument really worth including on the first day of school?” check out this or this.)

Lesson plan walkthrough

Each student will brainstorm at least five claims — or arguable statements — for sharing with their partner. To give you a mental picture, students in my room are most often seated as partners; the activity would also work well with students seated in groups, and with slight modifications would be amenable to students seated in traditional rows.

I begin by modeling something like this:

Okay, here are some facts about me: I love my wife and daughters; faith is important to me; my favorite food is the taco; I love teaching; and I'm pretty addicted to reading. Some things that I did this past summer include camping out West, speaking at conferences, and relaxing on my deck with my family. One of my core beliefs about students is that hard work over the long haul trumps lazy intelligence every time.

So that’s probably enough for my five. Now, how can I turn these into debatable claims? In other words, how can I state them in a way that you could argue with me? Let’s just try it; you'll notice that all of these are debatable — in the way we'll be speaking this year, they are claims:

- The four most beautiful women in the world are my wife, Crystal, and my three daughters, Hadassah, Laura, and Marlena.

- The most impactful historical figure is Jesus.

- There’s really no contest: the best food in the world is tacos.

- The number one best job on the planet is the one that I have: teaching you.

- The most relaxing way to spend a rainy day is by curling up on the couch with a good book.

- The best campground in the United States is a tie between Granite Creek in Wyoming and Sage Creek in South Dakota.

- Hard work over the long haul trumps lazy intelligence every time

After I share each arguable claim, I ask students to give me a thumbs up or thumbs down on whether it is debatable — this is how we check to see if something is a claim. Now it's their turn.

Their job is to draft five or more claims, just as I've done. I give them three minutes to do this, walking around all the while and coaching them to keep writing. This establishes another principle for us this school year: writing is partially about overcoming perfectionism and doing the work of getting words on the page.

After three minutes, students take turns sharing their claims with a partner. I give one minute for this task, and before it starts, I teach my students to shake hands, introduce themselves, and make eye contact. Laughter is encouraged during this time, as some of these debatable claims can be funny.

Finally, I ask for volunteers to read a claim that they wrote — only one. Inevitably, someone expands upon their claim —

e.g., “MSU is better than U of M because green and white are better colors; I know that some of you will think that's not true, but it is.”

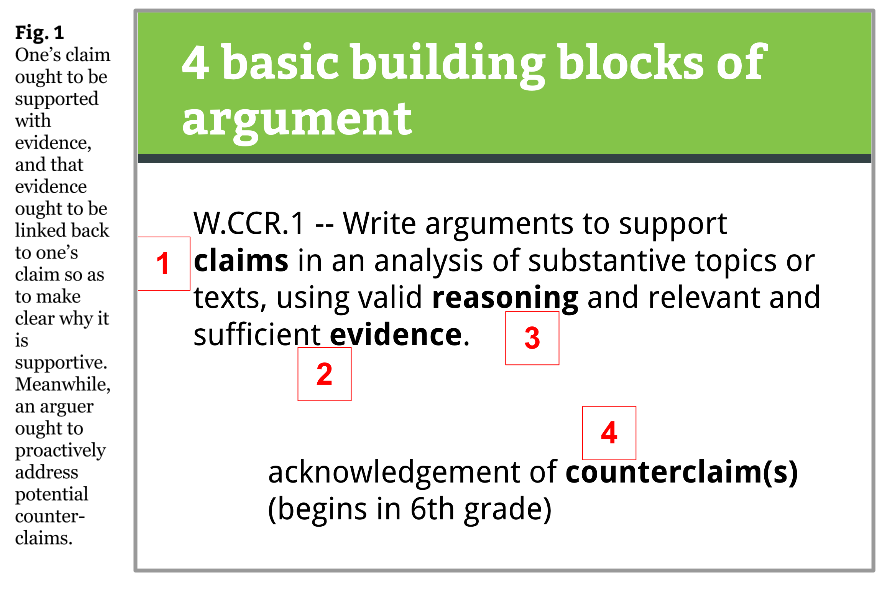

— and this gives me an opportunity to introduce up to three additional terms:

- evidence, for when the student uses a piece of data to back up their claim

- in the example above, the evidence is that MSU's colors are green and white

- reasoning, for when the student explains how the data supports their claim

- in the example above, the reasoning is that green and white are superior colors to U of M's

- counterclaim, for when the student anticipates what others might say and proactively responds

- in the example above, there is a hint of this — “I know some of you will think…” — but it's not developed.

Those three words, when combined with claim, form what I teach as the four argumentative building blocks (see Fig. 1). These things need not always be in a set order to build a solid argument, but they are always found within solid arguments. I think of them like LEGO blocks.

Lesson objectives

From the measurable perspective, my goals are:

- that students will understand or review what the word “claim” means. They will use that understanding to create claims of their own, and I will be able to monitor their understanding through reading what they write (as I walk around) and listening to what they share.

- that students will learn something about their partner (and thereby begin creating our classroom community).

From the “I want to create a legendary classroom” perspective, my goals are:

- that students will begin seeing both the centrality of argument and the nature of it. Argument isn't just a one-and-done unit we'll complete — it's a way of thinking more clearly, and it's part of how we're wired. It's not negative and antagonistic — it's fun, collaborative, and creative. (I owe Jerry Graff and Cathy Birkenstein for this attitude toward argument; more below).

- that students will begin seeing that, in this class, they'll be thinking, every day — even on day one.[hr]

Thank you to Jerry Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, authors of the popular They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing, for giving me my present understanding of argumentation, and for teaching me its centrality to a life of the mind and its democratizing effect on student achievement.

kad4 says

Dave- I really enjoy your posts. This is a great way to open the school year -except for one problem. I teach students that matters of taste are not arguable claims…sorta blows your examples. Have any ideas on how to get them to quickly brainstorm meatier claims?

Saja says

I was wondering the same. I think the activity is a wonderful way to introduce the idea and break the ice. But I’m curious about the next step: how do you move from “matters of taste” to substantial claims.

davestuartjr says

I would say that matters of taste aren’t arguable claims unless supported by evidence and reasoning. Or, perhaps more clearly, while “I like tacos” isn’t an arguable claim, “Tacos are the best food in the world” is, because “I like tacos” is simply a statement of taste, whereas “Tacos are the best food in the world” is a claim statement that could conceivably be supported by legitimate evidence (cost, health benefits, survey data — data points like that are conceivable).

This lesson is meant to quickly get students aware of the ubiquitousness of argument — I hope that some might realize that they actually argue a lot with their friends and family, be it about baseball or food or movies or books, and that that argumentative experience is something to build upon this year in a more rigorous, academic sense.

I hope those thoughts are a bit helpful, at least!

Heather Peska says

Love this idea – thank you so much!

davestuartjr says

My pleasure, Heather!

Shelby Denhof says

I dig this. I’m brainstorming about how to adapt these ideas for my first day plan.

davestuartjr says

Thank you, Shelb!

Brian says

Dave,

This is great! I was just stressing about a great “hook” activity to open the school year with and..BOOM…I come across this in my email. I love it and definitely plan on using it. Do you happen to have any handouts that go with it?

davestuartjr says

Brian, I’m so glad. Thank you for commenting! I don’t have any handouts — students listen to or watch me create/write some examples, and then they do likewise on any old piece of paper.

carla says

Per your example, I’ve advocated that the teachers I coach start their year by building a culture of “argument”. Not as aggressors, but as debators with evidence to support their claims.

Thanks for sharing!

davestuartjr says

Exactly, Carla — not as aggressors. Richard Fulkerson offers a helpful picture of the kind of argumentative culture we’re aiming at:

“…the goal is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own.”

–Richard Fulkerson, Teaching the Argument in Writing (1996), as quoted in Common Core Appendix A

Heather says

I am really excited to start my 13th year of teaching. Your ideas have really helped me get over a bit of a slump Definitely going to use the index cards and the argument activity on the first day. One thing for sure 6th Graders love to argue- LOL

Definitely going to use the index cards and the argument activity on the first day. One thing for sure 6th Graders love to argue- LOL

davestuartjr says

Heather, I’m so glad to hear it. And, yes: 6th graders do

Brian Backman says

This is a great idea. It reminded me of a TED talk called “Dare to Disagree” by Margaret Heffernan. In her talk, she emphasizes the importance of being prepared to defend and debate what you belief. She also talks about PhD candidates at the University of Delft who are required to submit five statements that they are prepared to defend.

davestuartjr says

I just watched the whole thing, Brian — great talk!

Laurie Schmid says

This is great! I will definitely incorporate some of this into my lessons. I’m a debate coach so when I teach argumentation, I use Claim, ‘warrant, impact. I see impact as being different from your reasoning. Impact explains why a particular argument matters and I think goes further than just explaining your reasoning. Do you introduce this idea of impact later on in your lessons?

davestuartjr says

Laurie, I like that idea of “impact” — I just hadn’t heard of it before. I will introduce Impact this year!

theallmans says

Dave, are you still doing this? Any modifications?