I'm finishing up a professional development trip to California, and during these final days of the trip, a troubling (yet unsurprising) article has come to my attention:

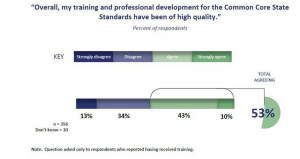

The article goes on to show that 47% of surveyed teachers would describe the Common Core professional development they've received as less than high quality.

And all I can do in response is facepalm, hard, because it doesn't have to be this way:

So without further ado, let me give a primer on what to do in a Common Core professional development so as to empower rather than burden your staff of professionals.

Step 1: Start with ultimate goals.

The beauty of the Common Core, in my mind at least, lies in the central focus of the standards: college and career readiness. That phrase occurs over 100 times in the document, and every one of the 32 standards is anchored in it.

So I like to begin by asking every teacher in a Common Core PD what their ultimate aim is for their students — in one sentence. Teachers say interesting things here: happy and successful; able to think flexibly and adapt to change; contributing member of society — these kinds of things.

I then show how the Common Core is aimed at something similar — not at test scores or stressing teachers out with minutiae lists or whatever. The standards aim at college and career readiness — and that's something we ought to want for all of our students. It's not about forcing kids into college or careers; it is about doing all we can do to empower them to truly have those choices.

Step 2: If you're leading the PD, you need to bone up on the standards and read through them, but not everyone on your staff needs to

It is insanely ineffective to have every teacher on a faculty reading through minutiae lists of standards. While I do think the Common Core are better than any previous list of literacy standards I'm aware of (primarily because they are simpler), there are still too many of them and it takes a fair amount of inference and additional research to determine which standards are the most important.

In other words, if you tell your teachers, “Teach the Common Core” and then give them a printout of every grade-level standard applicable to them, you are going to get a crazy crapshoot of results. Some teachers will go about revamping their whole curricula, insanely trying to “get to” or “cover” each one of the standards. Others will completely ignore your directive, angry that you would even suggest such a silly thing. And still others will develop neurotic disorders because they'll get to page 2 of the standards and start sweating, realizing they have no idea how to even begin bringing these things to bear on what happens in their classroom each day.

And just for the record, that latter teacher isn't necessarily ineffective. When we start saying “Effective teachers are those who adhere to standards — 'nuff said,” we start to create a toxic environment for high-performing teachers. Two or so years ago, I had never really read a standards document in my life — and I was a fairly successful, 5th year teacher! I got results in my classroom by a variety of measures. I sought to constantly improve.

Yet there did come that point in May 2012 when I decided I'd read through the Common Core to see what the freaking out was about and whether or not I was missing out by not paying mind to standards documents. During that first summer of blogging through the standards, I realized that they were, in fact, teaching me a bit about teaching. I saw them for what they need to be — “an opportunity to learn,” as Jim Burke has said.

The moral of the story is that every teacher has different professional development needs, so if you are leading professional development for a large group, the PD needs to be intentionally designed for the different skill levels. I'll talk more about how to do that successfully in a second, but first, if there's anyone in the school who should be intimately familiar with the standards documents, it's you, the PD facilitator.

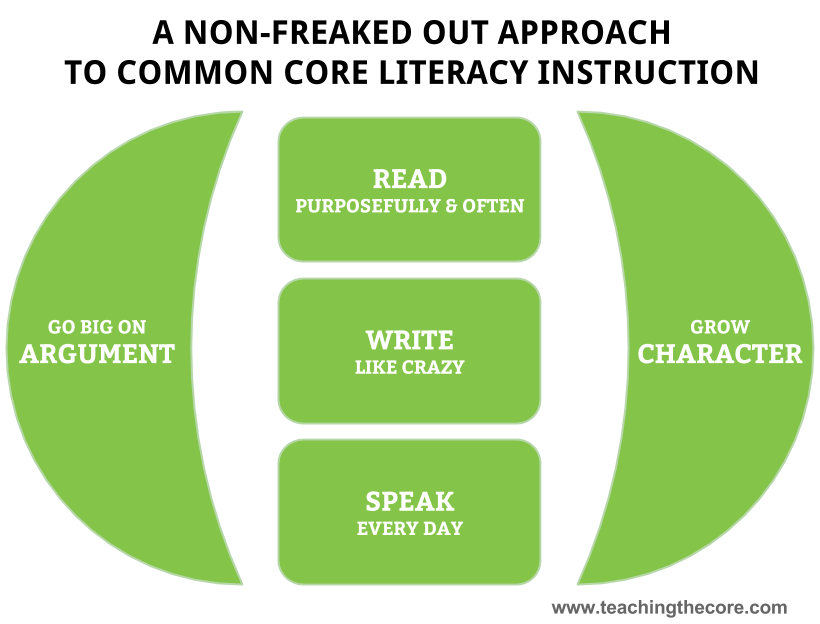

Step 3: Use a simple and deep framework for understanding and applying the standards

The only way I see of making Common Core PD successful for a variety of teacher skill levels is providing some way of “boiling down” the standards.

The goal should be a way of organizing the standards so that they are simple enough to understand in an hour or so, yet deep enough to explore for years. Below you'll see the “non-freaked out” framework I've come up with — I give it as an example of what I'm talking about but not as the only way of doing it.

As soon as teachers hear me tell them that this is what we'll be focusing on in the PD — not all 32 anchors (which aren't useless! I wrote a book about them, and it comes out in September *cheesy smile + glimmering teeth*) — I can almost hear the collective sigh of relief.

When I work with a school, I try to reinforce the idea that great schools

- Figure out overarching, end-of-the-day goals, and they make those goals clear and explicit to all involved

- Focus on the most important things they can all be doing to get their school from its current spot to where they want it to be.

- Set up a series of small wins along the journey from “Now” to “Where We're Heading”

So at the start of the PD, I go through each of the above elements — unpacking the why and the how. But for the how, I strive to think of what are the most critical, widely applicable “next steps” teachers can be taking. For next steps, try to come up with things that will empower every teacher to move in the right direction, but that easily differentiates for varying skill levels.

For example, with argument, I recommend starting with debate, one of the most underrated educational tools ever (unless, of course, you teach in an elite school — then your kids probably get the chance to debate regularly).

But I don't just say, “We should start with debate” — I also share a simple, highly manageable debate strategy called pop-up debate. A strategy like this is simple to teach to students but is also complex enough that I plan to be perfecting it for, oh, I dunno, the rest of my career or so. I'm serious.

And then rinse and repeat for the other elements — reading, writing, speaking, and character. For all of these, I provide a starting place for teachers, useful tips I've learned along the way, and then I say, “Okay, now let's talk — what are you seeing? How's this meshing with what you're already doing well? What needs to stay? What needs to go?”

When we overcomplicate things in PD, the majority of participants are sitting there frustrated, stressed out, annoyed, or planning tomorrow's lesson on a piece of scratch paper, and we're spending a ton of time explaining the overcomplicated concepts.

It's just a recipe for nothing happening in the long-term.

But when you bring a simplified framework that participants can grasp in an hour, people tend to be engaged at both the low-skill and high-skill ends of your faculty spectrum. It engages their professionalism because they say, “Yes, I can do this,” and also, “There's room to develop this into something really cool.”

A note on “Character”

I sometimes get misunderstood when presenting the above framework because character is nowhere in the standards (and that's a good thing). Specific character strengths (or noncognitive skills, if you prefer) are, however, critical if we're going to get kids actually doing the increased amounts of complex reading, writing, speaking, and arguing (thinking) they need to do to get college- and career-ready.

Some well-meaning educators say, “Well, the majority of students today will only read if we let them pick what they read or confer with them extensively or [insert something else].” But I don't think that's true. I think kids are unlikely to engage with a challenge if we don't teach them to do so, but I think they are likely to do it if we teach them how. Part of that “how” lies in the noncognitive skill research laid out in Paul Tough's How Children Succeed.

So while it's not part of the Common Core, it's still a critical part to getting kids to what the Common Core ultimately aims at — college and career-readiness — and just like the basic literacy practices in the non-freaked out framework, character is adaptable to any setting or content area. It's also highly motivating when teachers are told by their bosses that we as a school are going to emphasize something that will never be on the standardized test but will be critically important for the long-term flourishing of our students.

Step 3: Deeper and deeper

The beauty of simple, deep frameworks for the Common Core is that they can get your whole staff on the same boat, all rowing in the same direction. At the same time, such frameworks can motivate teachers without crushing them, and they can be explored at greater depths as individual teacher skillsets demand and the staff as a whole requires.

What has your Common Core PD experience been?

Are you among the 47% who wouldn't exactly call the PD you've experienced around the Common Core “high quality?” Do you think the approach outlined above would have made that PD better? Or maybe you've had some good Common Core PD — what was it like? What made it good?

Wage war on bad PD, Teaching the Core folks. Do it respectfully, but do it. It seriously does not have to exist.

Genieve says

Love this graphic. I can’t wait to share this with my administrators and my superintendent. Thank you for making CC worth fighting for at my school.

brie says

I will be framing my upcoming PD with this in mind. Thanks so much! Can’t wait for the book!

Matt Copeland says

Am liking the new graphic, Dave! Am also wondering about changing the “Write like crazy” (which could misconstrued as encouraging kids to write FAST) to “write and revise often” to focus on writing effectiveness just as we focus on reading purposefully. Also might change “speak every day” to “share and discuss everyday.” Speak, of course, would be included in “share” but so would the sharing student writing. “Discuss” might better envelop both speaking and listening rather than just speaking alone.

Angela says

Matt,

While I can understand your suggestions and desire for the use of more “Academic” language, after having been through the entire PD with Dave, if you read some of his other posts about writing and speaking it will become quite clear that his intention is not for students to write really fast nor speak without listening. The write like crazy notion is to get students writing as frequently as possible and in a variety of different settings for multiple purposes and that there is definitely still a need for polished pieces of writing where revisions and multiple drafts have taken place. I encourage you to check out some of his other posts regarding these topics. The simple, “non-academic” way of presenting his framework for an approach to literacy is part of the appeal for all audiences and its what gets them to sit up and pay attention to the rest of what he has to say.

Angela says

I have been fortunate enough to have Dave do this PD in my district and it was a huge success! My motivated, higher end of the spectrum teachers came away with some great tools to add to their tool belt and a much more common sense understanding of the common core and my difficult to motivate teachers came away motivated! Most importantly it has brought a focus and common language to the staff and as the instructional coach I can now approach our conversations from a different level because of that. Prior to Dave’s PD approach our teachers had attended several “common core” PD’s and they definitely fell into that percentage of people who still felt confused and battered by the common core.

Thanks Dave!

Jack Smith says

Excellent breakdown of Common Core professional development! The focus on actionable strategies and understanding content deeply is helpful for teachers aiming to improve their teaching practices. This post provides great clarity and motivation!