The Common Core does a pretty good job of laying out some key cognitive skills students need to have to be ready for the literacy demands of a career or college. Granted, we need to reduce the standards into a simpler, more power-packed set of focused literacy priorities (the non-freaked out approach being one possible example) if we're going to truly see literacy instruction expand in breadth and depth across a student's school day. But with that being said, I give my props to the standards for being the best list to date of what it means to be proficiently literate upon graduation from high school.

However, here’s the claim I’ll spend this post supporting (I've pawed around in the dark at it elsewhere, but that was quite a few months ago, and I've done more thinking in the interim): if you aim at the Common Core's goals (which are cognitive) and nothing else, you and/or a large amount of your students will begin to hate you and/or their life. A vague sense of frustration will live in your classroom, and you won't be able to put your finger on it.

Some will turn up their noses at the hyperbolic tone of that claim, so allow me to put it positively:

[box type=”info” size=”large” border=”full”]Research-based approaches to literacy acquisition must include a serious, strategic treatment of noncognitive skill development.[/box]

[box type=”note” icon=”none” size=”large”]

Time out: what are noncognitive skills?

Noncognitive skills are those things that aren't measured on traditional intelligence metrics (e.g., IQ) but are nonetheless being shown in study after study to significantly predict whether or not you’ll be successful. By calling them skills, I'm saying that, just like dribbling a soccer ball or writing your name or factoring an equation or reading closely, noncognitive skills can be intentionally taught and intentionally practiced and intentionally mastered.

Noncognitive skills are those things that aren't measured on traditional intelligence metrics (e.g., IQ) but are nonetheless being shown in study after study to significantly predict whether or not you’ll be successful. By calling them skills, I'm saying that, just like dribbling a soccer ball or writing your name or factoring an equation or reading closely, noncognitive skills can be intentionally taught and intentionally practiced and intentionally mastered.

If you've already heard of noncogs, it's probably at least partially thanks to the writing of Paul Tough, especially his breakthrough book How Children Succeed. (Also, if I'm not mistaken, the term originated in the work of Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman.) In the book, Tough shares the work of schools and social workers and students and researchers and economists and psychologists, work that coalesces into the strong suggestion that the USA’s obsession with standardized tests is founded on the faulty presupposition that success predominantly hinges on intelligence. In other words, Tough contends that we’ve put all our chips on intelligence, and we'd be wise to reconsider our bet.

The book is worth your time, but until you read it and for the sake of the rest of this post, just know:

- noncognitive skills are learnable habits, not in-born traits, and

- the two noncognitive skills that seem to get the biggest bang for their buck are grit and self-control.

That latter point doesn't mean that grit and self-control are the end-all, be-all — we'll discuss other noncogs later.[/box]

Here's what I mean by “serious”

I underlined serious in my claim at the start of this post because I think it's obvious that most teachers care about noncognitive skill development.

They want their students to develop a work ethic or to take ownership of their learning or to manage their time better or to keep away from addictive substances or to love learning/reading/books/life — things like that. Yes, I know this is crazy if you've been drinking some of the kool-aid of today's political discourse; I know it smacks the face of popular belief to say that teachers aren't actually lazy, worthless ingrates leeching off the public treasury, and that they actually care about their students.

(I think I accidentally hit the snark lock on my computer.)

But I would also argue that most teachers lack a systematic, simplified list of what noncognitive skills matter for their students' long-term flourishing. As a result, their attempts to instill noncognitive skills in their students are inefficient at least and, unfortunately, often largely ineffective.

So why do we lack these lists?

This answer goes back to Tough's thesis: the US educational machine has spent decades emphasizing cognitive skill development (reading, writing, mathematics), betting that if our kids are really good at these cognitive skills, they'll make for a better and more globally competitive workforce.

At the me-in-my-classroom level, this means that I, as an English language arts and world history teacher, am constantly told — by the high-stakes tests my kids and I are measured with, for example — that my efforts need to be spent improving cognitive skill development in my students. There's no test for noncognitive skills like grit and self-control — and, for the love of all that's good, let's please not make one — and therefore I expend time and energy on systematizing and simplifying these things for my students at the expense of what I'm actually being asked to do.

Yet simplified, research-supported lists do exist

Thankfully, there are those who have done the hard work of organizing the research around noncognitive skills into lists that are manageable for both teachers and student.

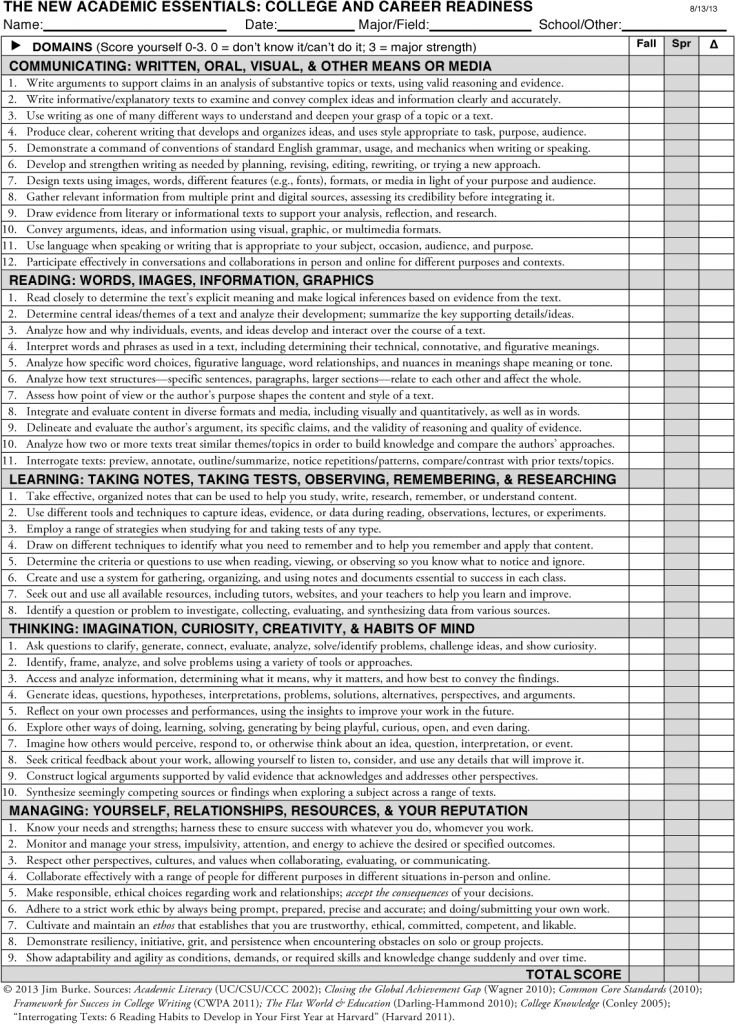

Jim Burke's list of “Academic Essentials: College and Career Readiness”

Jim Burke, high school teacher and author of quality teacher resources like The English Teacher's Companion and The Common Core Companion, has a list of Academic Essentials for College and Career-Readiness. I like this list because, on a single page, it includes all of the cognitive literacy skills and noncognitive skills he wants his students to master. Jim is a teacher-author who fights not for a particular philosophy or instructional bent, but rather he is a man in pursuit of one question: how can we teach better? In terms of noncognitive skills, see the Learning, Thinking, and Managing sections on Jim's list.

KIPP's list of “character strengths”

If you've been around the blog for a while, you know that in the academy I teach, my colleagues and I organize our noncognitive skill instruction around the KIPP network's list of character strengths. Initially, we used this list because it was featured in a New York Times article Paul Tough wrote as part of his work preceding the release of How Children Succeed. Yet we've stayed with the list for more than two years now because:

- It's as simple as seven strengths.

- Here's where some people get angry about what I do here at Teaching the Core. They cry, “Simple isn't better. Teaching is complex.” But I would argue that anything that's got a shot of really having an impact in education should be complex enough to explore creatively for years and yet simplifiable enough to understand, in some fashion, in as little as an hour. We need simplified literacy instruction frameworks like the non-freaked out approach if we're to see kids getting more and better literacy instruction throughout their school day in all their classes. Think of how simple an acorn is, and yet how much potential for longevity and complexity it contains.

- KIPP breaks each strength into a set of observable, behavioral indicators.

- This means we avoid the effects of buzzwordification (and, as Anne King [I think?] tweeted in response to my Obituary for Close Reading, grit is gravely at risk of death by buzzwordification; Aflie Kohn has famously called grit a “fad,” and some of his non-political points are valid) and have a set of tangible measures to assess ourselves on the skill. These measures should not be used to create the next generation of standardized tests, mind you, but they are useful for meaningful self-reflection.

- KIPP's list is being used by hundreds, maybe thousands, of teachers around the country.

- This means we've got a big group of people to collaborate with on figuring out how to best develop this particular set of noncognitive skills in ourselves and our students.

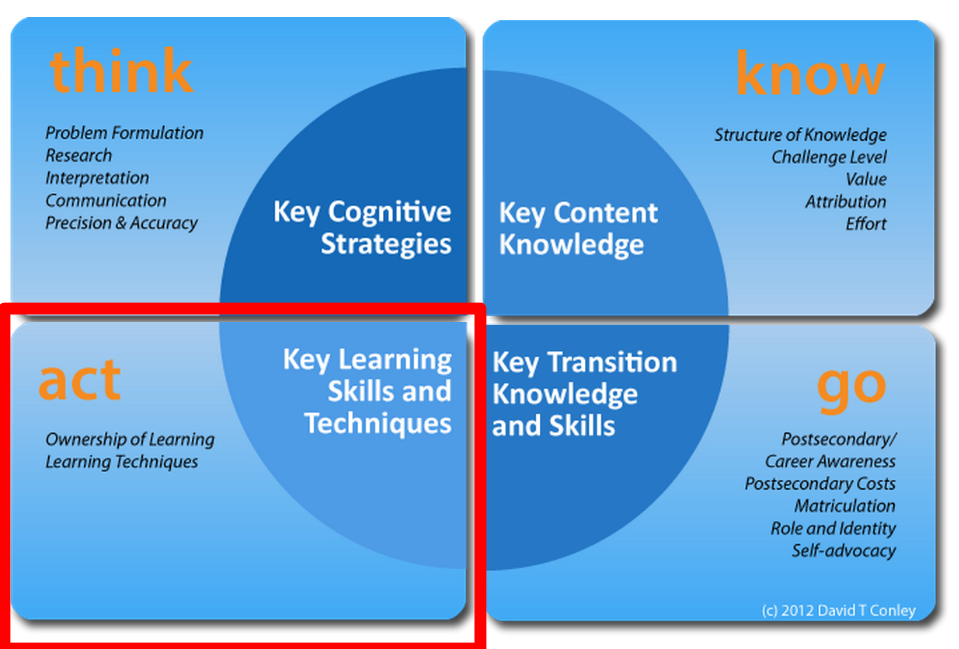

David Conley's list of “key learning skills and techniques”

David Conley, author of College Knowledge, College and Career Ready, and College, Careers, and the Common Core, is like the guy who invented the term college and career readiness. In his most recent book, he shares a “Four Keys” framework for understanding college and career readiness, and one of those keys consists entirely of noncognitive skills (see image above).

David Conley, author of College Knowledge, College and Career Ready, and College, Careers, and the Common Core, is like the guy who invented the term college and career readiness. In his most recent book, he shares a “Four Keys” framework for understanding college and career readiness, and one of those keys consists entirely of noncognitive skills (see image above).

Under Ownership of Learning, Conley lists:

- goal setting

- persistence

- self-awareness

- motivation

- progress monitoring

- help seeking

- self-efficacy

These are solidly under the noncognitive skill umbrella. (I got those from his College, Careers, and the Common Core book, in which he explores each skill at a greater length.)

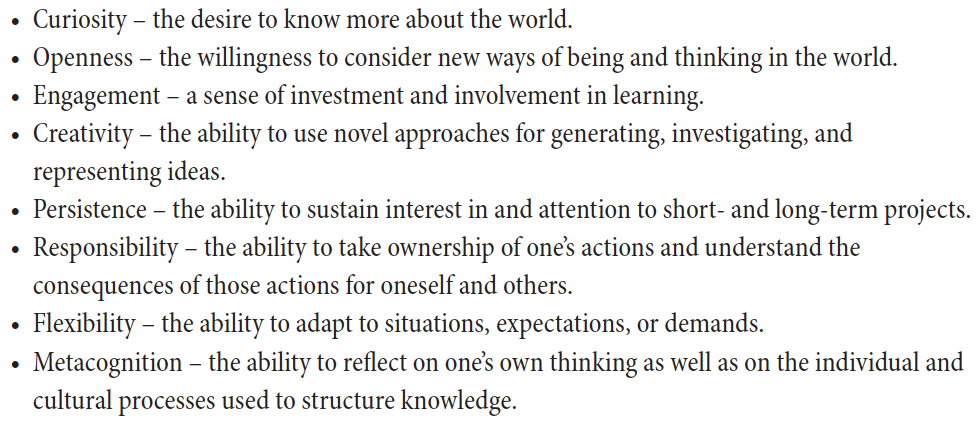

NCTE's list of “habits of mind” for success in postsecondary writing

Finally, there's the list above — NCTE's list of mental habits for dominating postsecondary writing demands. I just came across this one today while writing this post, so I'm not as familiar with it as I am with the preceding three, but it's another example of the kind of serious, strategic approach to noncognitive skill development I'm talking about. This one is interesting in that it focuses on noncognitive skills helpful for postsecondary writers.

I'm sure there are other lists — please share them in the comments.

Descriptive, not prescriptive

Some will argue that the lists I've shared could be used to create dead, legalistic approaches to teaching. They'll say that you can't force noncognitive skill development just by making a list of the skills most integral to a flourishing life.

These people are right! Such lists, just like the Common Core's list of cognitive literacy abilities, only work when teachers and students have room to find their way within them, to “own them.” You only become good at badminton by playing badminton; creating a systematic list of the most important badminton skills and then telling players to become good at them accomplishes nothing; you've got to #hittheshuttlecock, as I've said before.

This reminds me of an argument that baller teacher-author Penny Kittle makes in Book Love (a love of reading, by the way, is a noncognitive skill — it can be learned, and yet it's not measured by IQ tests — and inarguably a critical one).

This reminds me of an argument that baller teacher-author Penny Kittle makes in Book Love (a love of reading, by the way, is a noncognitive skill — it can be learned, and yet it's not measured by IQ tests — and inarguably a critical one).

In that book, Penny titles a section with the claim “good teaching is based not on a system but on relationships” (p. 35-6). I agree with part of this claim — great teaching is based on relationships, and the magic in classrooms where kids transform is almost always attributable to an instructor who is connected to kids and uses those connections to connect kids to X (science or reading or history or what have you; in Kittle's case, she masterfully connects students to books, and this results in a helluva lot of reading).

The problem with the claim, though, is that I think we need relationships and systems to maximize the impact of our teaching, especially if great teaching is going to spread as far as it can go. Professions have frameworks and systems for describing best practices, and ours is a profession. The systems need to be smart, robust, authentic, and flexible; they need to be simplifiable enough for new or low-skill teachers to grasp, and complex enough to allow for experienced, high-skill teachers to further research and explore. These kinds of systems are a tall order, I realize, but at the end of the day, I think great teaching can be based on them and relationships.

To get us back to our topic, the key, I think, lies in viewing systematic noncognitive skill lists as descriptive rather than prescriptive. Jim's list is a description of what proficient students can do. The KIPP list is a description of a set of habits that increase the likelihood of positive life outcomes. Such descriptions are not just helpful, they're critical!

The problems come when we take prescriptive approaches to these descriptive lists — and I think that's what Penny is wisely getting at in the above example. The minute these things get reduced into a boxed-up curriculum or a textbook, it may be time to sign up for Mars One. But until then, such lists serve as an accessible, common language for the “what else” questions we teachers too often pursue in isolation: literacy plus what else will make my students most likely to flourish in the long run? Science plus what else? Math plus what else?

We need to start talking explicitly about noncognitive skill instruction when we talk about literacy instruction

And so I close with the full realization that this post still represents so much rough draft thinking. But here's the gist — the literacy instruction conversation needs to include the noncognitive skill conversation, and we need to move forward with agreed upon language for referring to what skills matter most so that we, as a community of professionals, can get to the much more exciting work of exploring how in the world we get kids developing these highly predictive, literacy-enhancing skills.

Leave a Reply