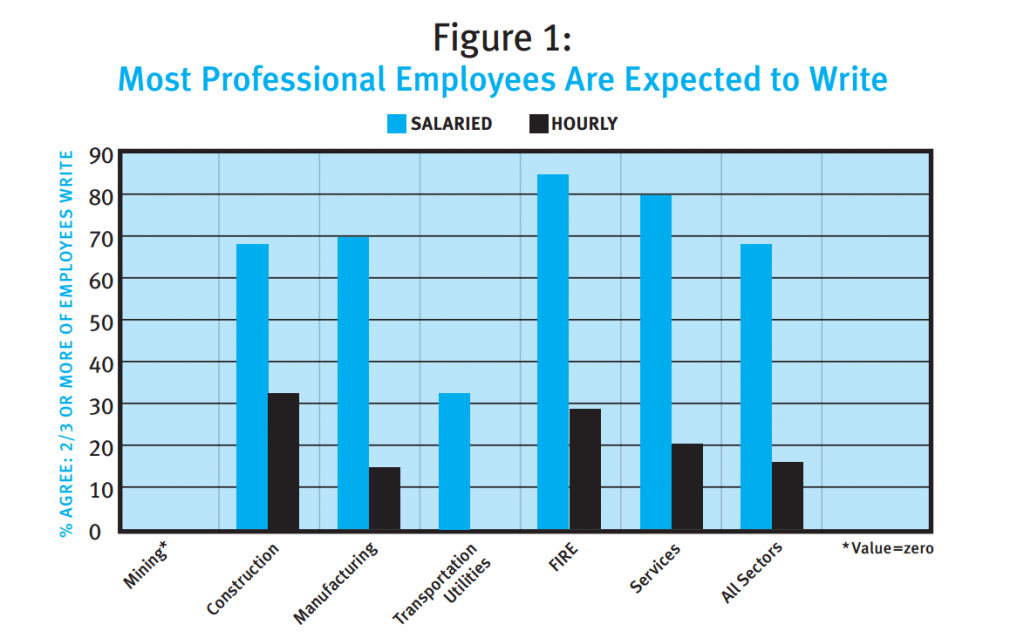

I struggle to imagine putting together a solid argument for why we wouldn't want all of our students to be capable writers when they graduate. Writing well is an obvious good. While much fuss was made about newfangled twenty-first-century skills, one very old skill that seems to be only increasing in importance is writing. Here we have the importance from an economic angle:

Unless you're a future miner (apparently), writing matters — especially if you want access to the salaried jobs that typically coincide with a middle class lifestyle.

And of course, just as school should not be conceived of as a place that produces widgets prepared to enter the economy, writing is not only about dollars and cents. A proficient writer is able to journal through mental health struggles, articulate complex thoughts, and communicate in a measured manner. Writing makes us better readers, better thinkers, better speakers, and better listeners. Through writing, we can inform, explain, argue, entertain, and inspire. This isn't just for teacher/blogger/nerdy types (I don't know any of those, of course); it's for mothers, employees, citizens, dreamers, and spouses.

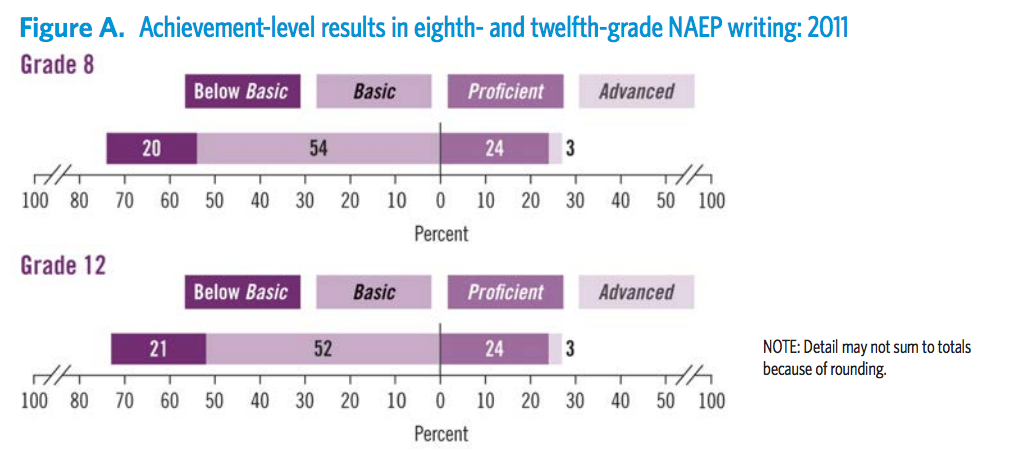

Unfortunately, those who graduate today with the ability to write have one more huge advantage: they're rare. According to the most recent (as of this writing) Nation's Report Card on Writing, only about a quarter of kids and graduates are able to write proficiently.

We're not talking about the ability to mimic Shakespeare here — proficient writing is the ability to compose an email that someone can read and understand without difficulty. As NAEP says in their report, this is the ability to accomplish one's communicative purpose in writing. When you're proficient, your writing does what it was supposed to do. More than a quarter of our kids need to be able to do this.

The solution? I think that David Conley says it best:

“If we could institute only one change to make students more college ready, it should be to increase the amount and quality of writing students are expected to produce.” (from “The Challenge of College Readiness” in Ed Leadership, 2007)

To paraphrase Dr. Conley (who, for what it's worth, was researching college and career readiness years and years prior to the Common Core popularizing the term), this is what it takes to make the next report card a better one:

Step One: Increase the quantity of writing students are expected to produce

Step Two: Increase the quality of writing students are expected to produce.

In most schools, the fruit hangs so low in these strategic initiatives that it is practically underground.

patrycja says

David, I am a long-time reader of your blog, but this is my first comment. First, let me take the opportunity to thank your for the inspiration and the tips each week. I have also bought your grammar bundles (I am not sure the exact title), which I find to be very thorough, and I look forward to using it next year in my English grades 8 and 9 classes. As for this blog post, I posted it to my Google Classroom for my students to read and showed some classes the graphs on my board.

The fact that so few students graduate capable, articulate writers is a serious concern. The lack of good writers is not only a problem in the United States, but it is also a problem here in Canada, where the standards for great writing have declined.

One major cause for this decline– in my opinion– is the deemphasis on rote memorization, such as the memorization of grammatical rules, sentence structure, uses of punctuation, etc. and the emphasis on creativity over clear communication. Because creativity is our aim– not clear communication– we teachers are pushed to assign more poster assignments, dioramas, movies, or art-based assignments.

When we downplay writing assignments in our English classrooms, be it essay or paragraph or letter writing assignments, we should not be surprised that students lack writing skills.

I look forward as always to reading more of your writing. Thank you for all the honesty and insight you put into your articles.

I enjoy each one. Best from Canada.

patrycja says

On a related note…when I first started teaching, I was incredibly passionate about teaching English because I saw as you did the connection it had to my students’ life outcomes.

Back then, I wrote about the power of learning English to inspire some students, and I still include it in my printed textbooks at the start of the year:

https://blackboardtalk.com/2012/12/30/why-teaching-and-learning-english-is-important/

I am happy to report that I am still as passionate about teaching English!

davestuartjr says

Patrycya, it’s been fun going through your comments today and doing some reading on your blog. I always enjoy meeting a colleague I share so much in common with, thanks to the Internet. Best to you in Canada from Michigan, USA!

Lauren Robinson says

Dave,

I am also a long-time reader and first-time commenter. I completely agree with the message of this post and the other more recent ones you’ve written regarding writing, grading, and feedback.

One struggle that I experience, however, is the student expectation that I grade EVERYTHING THEY DO. I also see students imply that they will not complete any task that is ungraded. I do not tell them that an assignment will not be graded, but I find that, as a result of this way of thinking, I play a “gotcha” game, randomly grading assignments to “prove” that I’ll keep them accountable.

Do you have any advice for me? I know there has to be a better way!

Many thanks,

Lauren Robinson

davestuartjr says

Just keep speaking against it, teaching against it. The goal is mastery, not a grade. But know that you are fighting an uphill battle — it’s just a worthy one, that’s all.

I’m sorry I don’t have better advice, Lauren!

Yours,

Dave

David Wollor says

Writing will always be fundamental as reading.

jennylau123 says

I found few helpful articles on this site : https://speedypaper.com/help_with_essay_writing

Can you check plz?

MBA Report Writing says

Such a nice post, keep providing good resources.