In The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own, I lay out an approach to student motivation in which Five Key Beliefs can be influenced using just 10 basic strategies.

The seventh of those strategies is Woodenization.

- What is it?

- How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

- Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

- How do I get started with Woodenization?

- What common problems do you see with Woodenization?

- I don't know the best way to teach my students to do X learning behavior. How am I supposed to pretend that I do?

- How am I supposed to teach one way of doing something when my students are individuals or there are so many good ways to do something?

- Why is it my job to teach these things? I've already got enough on my plate.

What is it?

- It's named after John Wooden, who famously taught his UCLA basketball players how to put on their socks and shoes.

- Here's an article where I explain the strategy.

- The gist is this: For any learning-conducive behavior you want your students to do, clearly and effectively teach them how to do that thing well.

- Here's an article where I differentiate “Smallies” from “Biggies.”

- Here's an example of how I teach students the “Biggie” of taking notes for learning.

- Here's a video testimonial from a student who drastically improved his grasp of effective note-taking effort. This happened, in large part, because of Woodenization.

Let's go into a bit more depth on this.

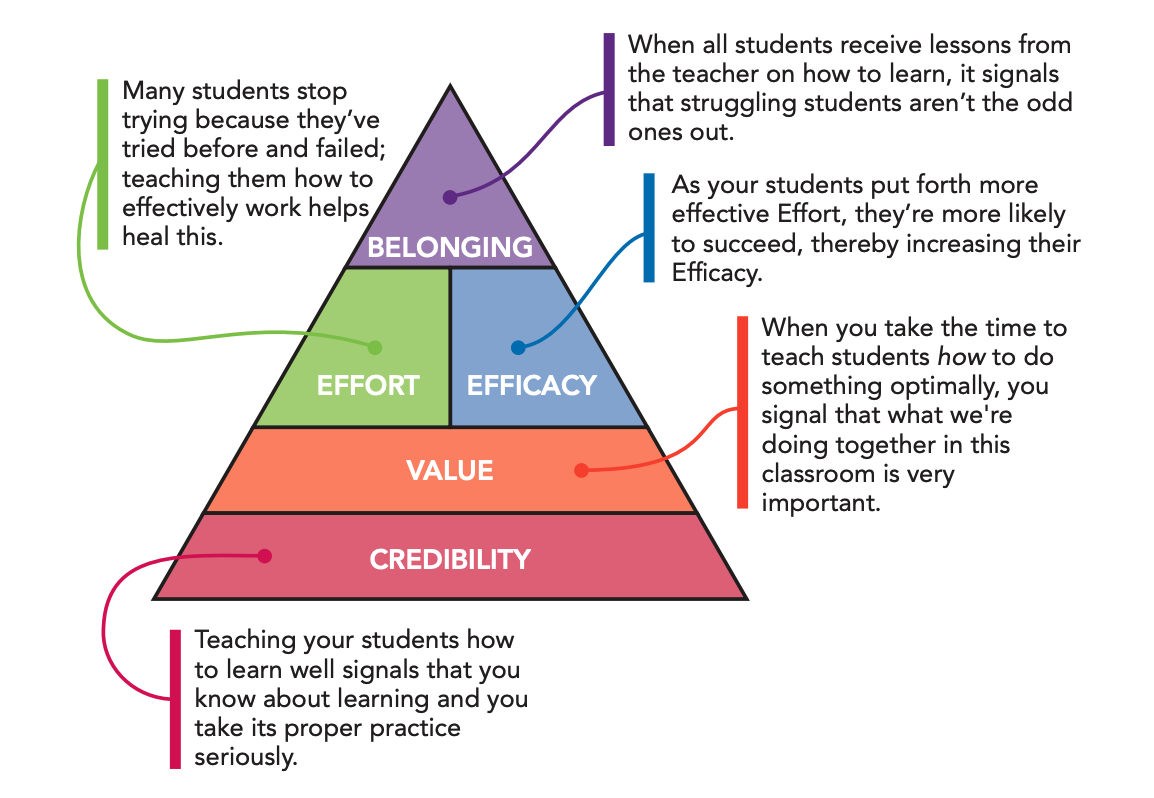

First, Woodenization is targeting a specific portion of the Effort-Efficacy Flywheel, which I explain further here.

What we're trying to do is diminish the common classroom problem of ineffective, ill-guided student effort. This is done very simply: by teaching students what effective effort looks like.

The strategy is named after John Wooden, who often argued that much of his coaching philosophy could be gleaned from the first activity he did with his players each year: teaching them to put on their socks and shoes.

What's remarkable in the quotation above is how lengthy it is. Wooden put a great deal of thought into what effective shoe-tying looked like, and he brought that clarity to his players.

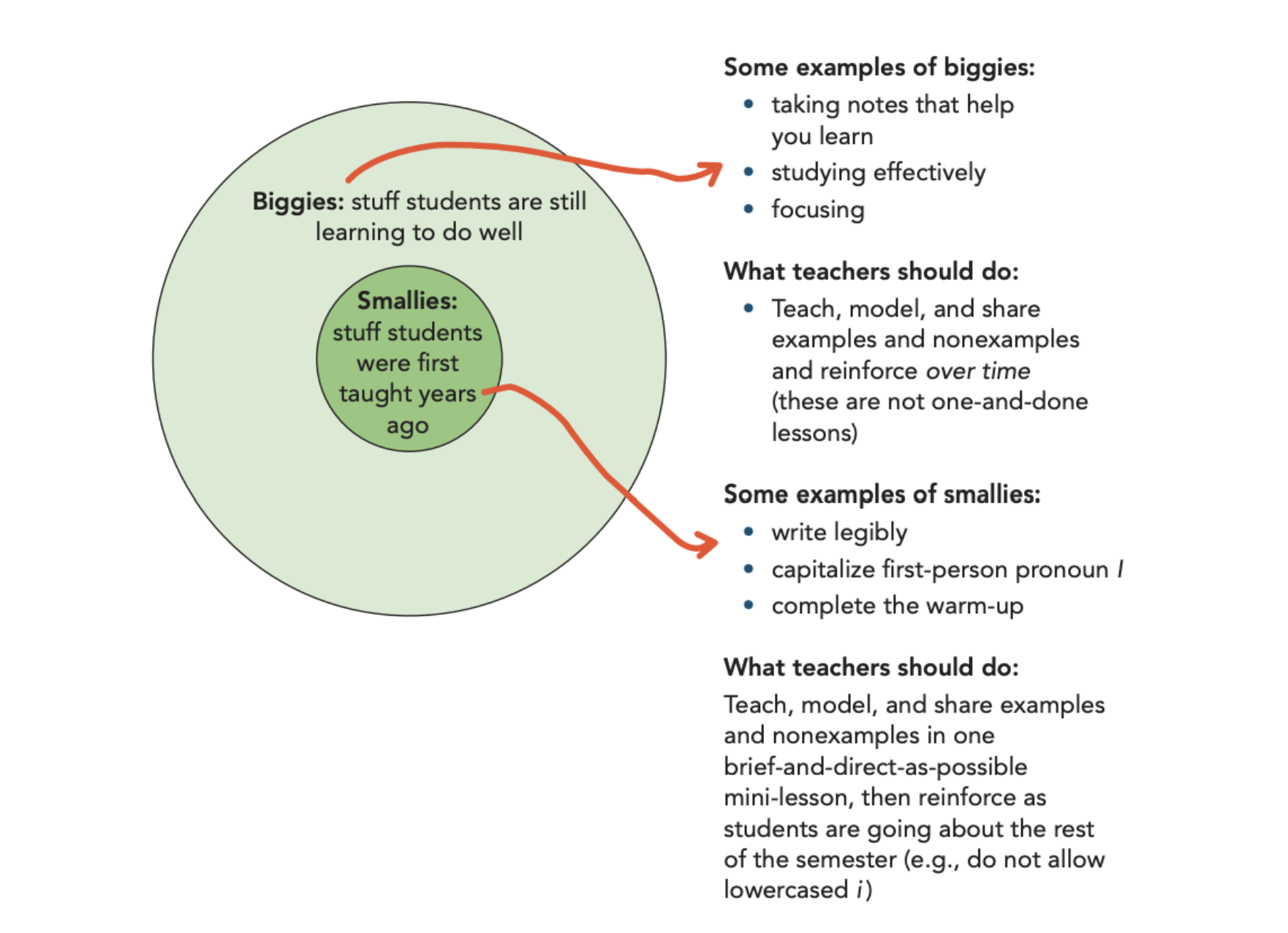

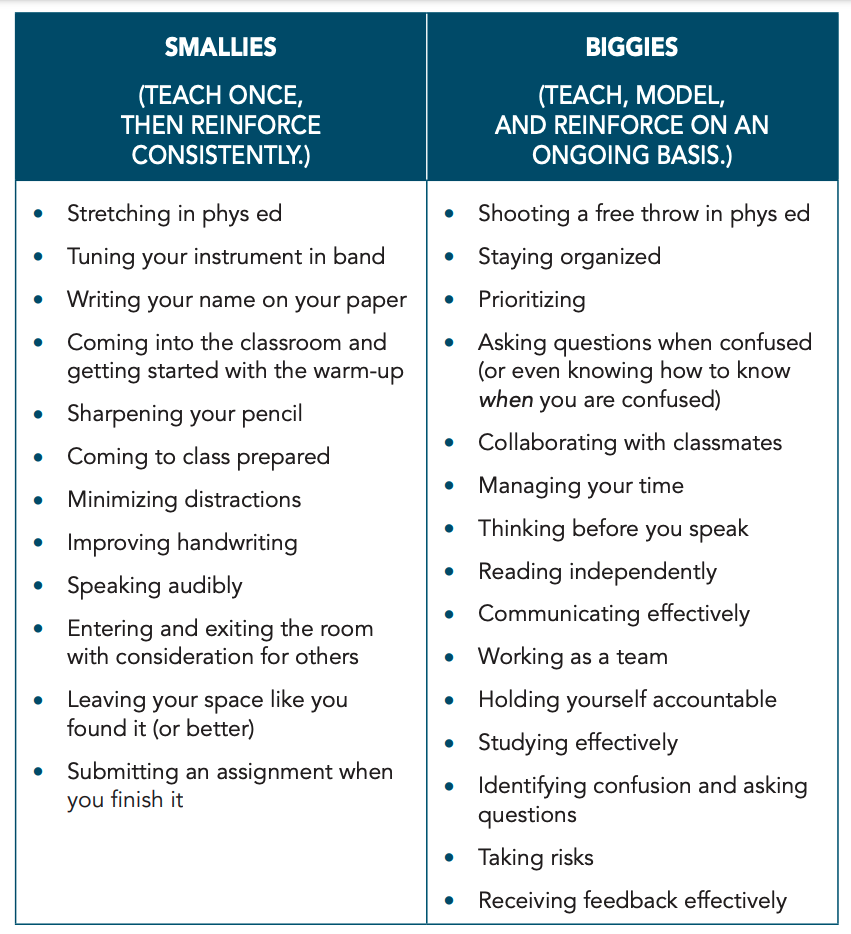

Shoe-tying, of course, is a simple task. It's what I call a “Smallie.” Smallies don't take more than a mini-lesson to teach; after that, they just need reinforcement. If a player's shoe comes untied during practice, Wooden addresses just that player. He doesn't need to spend whole-team time on the shoe-tying issue again once he's taught it. It's a Smallie.

Biggies, on the other hand, take many mini-lessons. In basketball, this might be something like passing the ball or shooting a three-pointer. Lots of practice, examples and non-examples, coaching, teaching, modeling.

Here are some specific examples of Smallies and Biggies in secondary classrooms.

How does this strategy influence the Five Key Beliefs?

While Woodenization is found in the Effort and Efficacy chapter of The Will to Learn, it has an influence on other beliefs as well.

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About This Strategy

How do I get started with Woodenization?

Step 1. Brainstorm a list of all the behaviors you wish your students would use when working in your classroom or at home. No behavior is too small or big at this point. If it's a learning-conducive behavior, write it down.

Step 2. Sort your list into “Smallies” and “Biggies.” Use the graphics above to help you do this. The rule of thumb is this:

- Smallies are something that students in your age group could be reasonably expected to have mastered prior to you teaching them. Things like “capitalizing I” or “turning your work in” would go here.

- Biggies are something that students in your age group can be reasonably expected to still be working on. If you teach high school, is the behavior something that college students or folks in the workplace struggle with? Then it ought to be a Biggie in high school. It's a skill students are still developing.

Step 3. Make a plan for how exactly you'll teach these things.

What common problems do you see with Woodenization?

The most common error teachers make is mis-categorizing a Biggie as a Smallie. Us secondary teachers can be pretty misguided at judging what students “should” be able to do with 100% consistency and proficiency by the time they reach us.

For example, one learning-conducive behavior that should be on everyone's list is “Focus on the task at hand.” Shouldn't a tenth grader be able to do this?

Well, let's see. How do I do at “focusing on the task at hand,” especially when the task is something given to me versus one I chose to do of my own volition?

You see where I'm going? Adults struggle with focusing on the task at hand — and we especially would were someone to transplant us into the shoes of a high schooler for a day.

However, “focusing on the task at hand” is a practicable, improvable skillset. It's just that it's a Biggie, not a Smallie. It needs instruction, tips and tricks, feedback, examples and non-examples.

- For an in-depth look at how I teach the Biggie of effective note-taking, see this article.

I don't know the best way to teach my students to do X learning behavior. How am I supposed to pretend that I do?

Don’t pretend. Learn!

- At your next department meeting, ask the team, “Does anyone have a good method they teach students for X?”

- Google your question with a query like, “What is the best way to X?” You’ll need to sift for quality, but it’s likely the first page of results will return some gems. You may even be able to excerpt something that you find and give it to your students as an article to read and annotate at the start of your next class.

- Search your query on YouTube. As with a Google result, an excerpt from the video may serve well as a resource when teaching your students the behavior you’re after.

- Find your nerdiest colleague and ask them if they’ve come across any tips for X in the professional literature.

And hey, have fun learning this stuff! You’ll use it all the rest of your career.

How am I supposed to teach one way of doing something when my students are individuals or there are so many good ways to do something?

You don’t need to sell your way as the only way to complete a learning behavior. But it’s not a waste of time for you to arrive at a settled sense of what you’ve noticed works best for students. Remember, your students have lots of teachers. They’ve had lots before you. They’ll have lots more after. You don’t need to be the end-all, be-all teacher for them. But what you do need to be is someone who is knowledgeable about how learning works best in a class like yours.

After all, if your students do get lots of different examples in their education of how to take notes, is that such a bad thing? According to one study, the more conceptions of learning that students have — e.g., learning is taking in new information, learning is developing oneself, etc. — the more likely they were to do well in school. In short, there is some benefit to students being taught multiple ways to do things.

At the same time, research in cognitive science is far enough along to where we do know that some strategies and methods just don’t work well. For example, at the start of this strategy, we touched on students’ overreliance on ineffective study methods, such as rereading and highlighting. A teacher would be remiss, then, to teach students that the best way to study is by rereading the text.

Another example of this would be teaching students to let their learning styles guide their study methods. Despite decades of studies, learning style theory — the idea that if students are allowed to learn according to their learning styles, they will achieve more than if they are required to learn some other way — has yet to be empirically corroborated. Because of this, I do not recommend teaching learning style theory to students.

Why is it my job to teach these things? I've already got enough on my plate.

When I teach this strategy to groups of colleagues (more on my in-person services here), I sometimes hear pushback to the tune of, “Oh great — here’s another thing being added to my plate. How typical.”

I do get the sentiment. As a classroom-based plate-holder myself, I, too, have spent time feasting at the more-than-you-can-eat initiatives buffet. However, I don’t think Woodenization is this kind of a thing.

What we’re doing with Woodenization is, in the long run, making our jobs much easier and simpler as teachers. Just consider: How much time have you spent in your career remedying situations that would have never arisen had students just done the things you asked them to do? Revised their papers, turned in their assignments, kept unit objectives organized, turned in the permission slip, written their name on their papers — how much time?

What we’re after with Woodenization is the same thing John Wooden was after: For the small price of five minutes of instruction and relentless reinforcement thereafter, Wooden likely never dealt with players who became injured or ineffective due to ill-fitting shoes. And even more than this, Wooden signaled something to his players each time he taught things like shoe-tying (a Smallie) or how to pass a basketball (a Biggie): “I know what I’m doing. I care about your success. I’ll leave nothing to chance. And on this team, our efforts will pay off — you can count on it.”

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: You get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply