Back when I first started blogging, I remember coming across an idea buried in the Common Core Appendix A. It was the most mundane-seeming of paragraphs, buried in the most mundane of documents. And yet, to me, it was revelatory.

Here it is:

Grammar and usage development in children and in adults rarely follows a linear path. Native speakers and language learners often begin making new errors and seem to lose their mastery of particular grammatical structures or print conventions as they learn new, more complex grammatical structures or new usages of English, such as in college-level persuasive essays (Bardovi-Harlig, 2000; Bartholomae, 1980; DeVilliers & DeVilliers, 1973; Shaughnessy, 1979). These errors are often signs of language development as learners synthesize new grammatical and usage knowledge with their current knowledge. Thus, students will often need to return to the same grammar topic in greater complexity as they move through K–12 schooling and as they increase the range and complexity of the texts and communicative contexts in which they read and write.

I found such a deep emotional resonance with this paragraph — which is weird, right? It's not an emotional text. But for me, it clicked into place a lot of observations I had been having in my classroom. For example: Why did John Wooden's first lesson seem instructionally genius to me? And why did Doug Stark's mechanics curriculum work so well in his room and in mine (and, since then, in so many English-teaching school systems around the world)?

There are so many principles in that paragraph, especially for us secondary teachers. You see, we can tend to assume that if a student doesn't demonstrate competency in something it's because the teachers before him or her failed. It's an ugly tendency — blaming my work problems on the imagined failure of others — but folks who teach secondary know what I'm talking about.

The thing is, the Appendix A paragraph shines needed light on this error:

- Schooling and grade levels are linear, but student learning rarely is. Human beings are a (beautiful, learnable) mess of complexity.

- Student errors in my grade level may not be signs of missed learning previously. Instead, they may be signs that new learning is happening and boundaries of capacity are expanding. In other words: errors are promising signs that I'm doing my job.

- The best response to errors, then, is teaching. “Students will often need to return” to the same old topics except at the new grade level's complexity.

A bit later in the paragraph, there's a word that encapsulates this: recursivity. Learning is recursive.

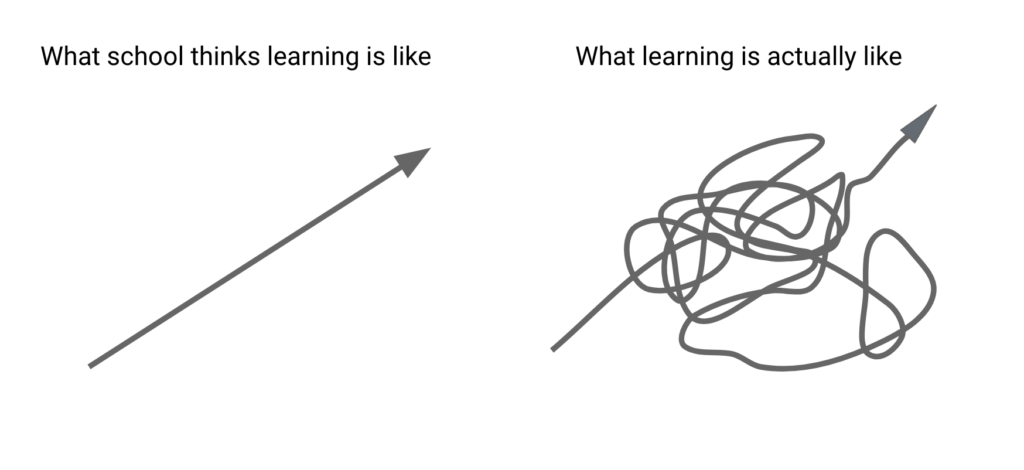

You've seen this meme, right?

But actually, THIS

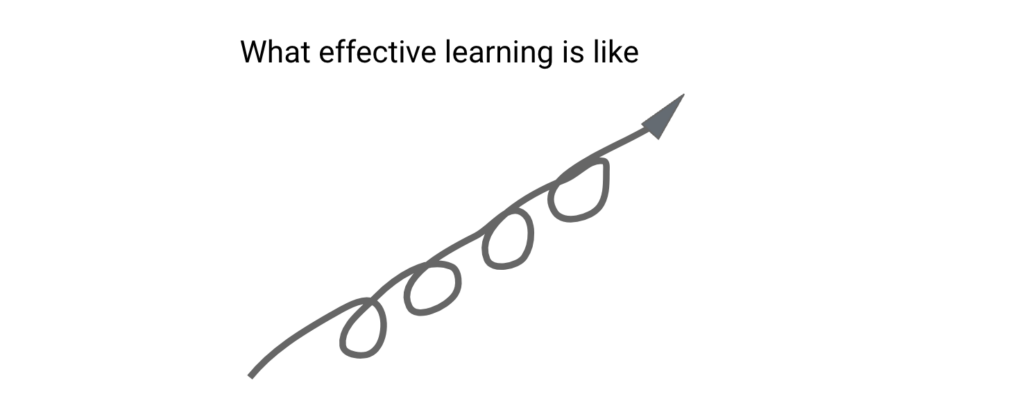

THAT is what recursivity looks like. THAT is why, no matter what grade level you teach, you've got to take the time to teach the skills that success requires.

- If you teach ELA, you need to teach mechanics, teach looking up unfamiliar words, teach navigating complex texts, teach identifying a choice reading book that you'd like to read.

- If you teach history, you need to teach note-taking, teach written response, teach discussion and debate.

- If you teach science, you need to teach the methods science hinges on, teach the vocab, teach the history.

- If you teach Phys Ed, you need to teach how and why to stretch, how and why to move one's body, how and why to physically challenge oneself.

And so on.

What you just can't do, in other words, is assume that because you teach ___ grade level, the skills should be there. Because even for the hard-working students who've had the hardest-working teachers, the journey isn't finished. The learning isn't done. Synthesizing your grade level's complexity is going to look like bouts and fits of regression.

That's learning.

Messy? Yes.

But understandable, too.

Best,

DSJR

Leave a Reply