Dear colleague,

Today's article is a bonus for you as we enter the holiday season. If you're not sure of a good gift for someone you treasure, I hope it helps. But more than that, I hope you'll be inspired by the wisdom of Bill Watterson. — DSJ

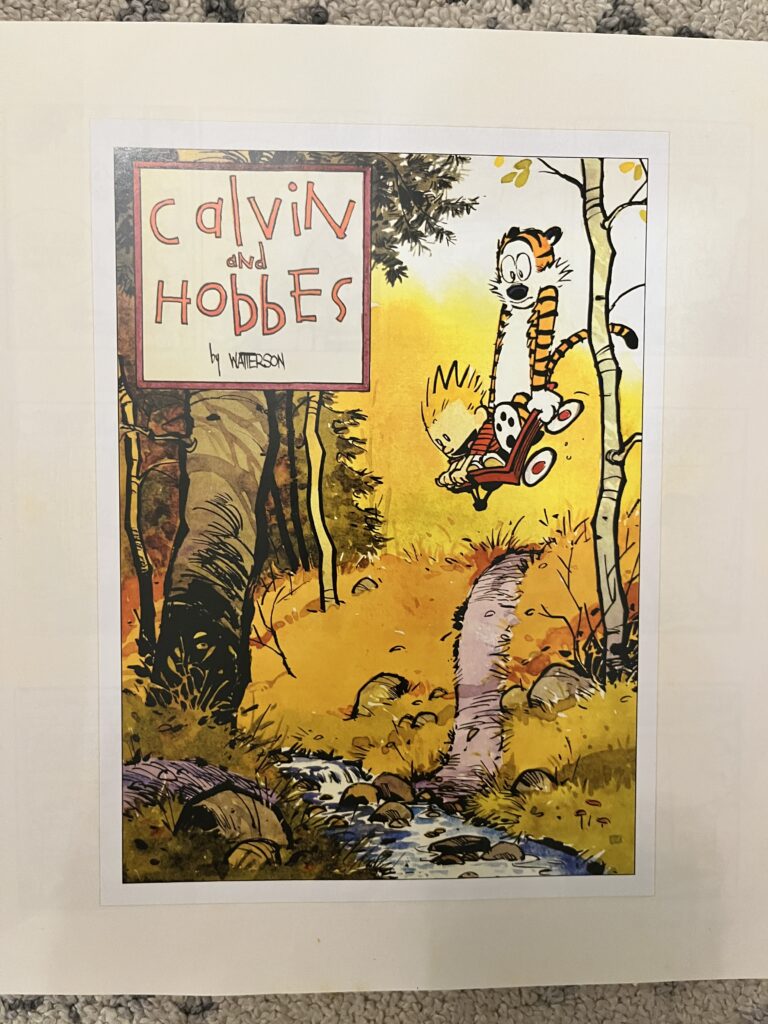

The single best gift I've ever bought for my children is The Complete Calvin and Hobbes. It's a boxed set of four separate volumes — perfect for our four children — and just about every day I find a volume in one kid's room, another on the lap of a child in the car, and another on the living room table. My son loves paging through and looking at the full-page spreads, his eyes in a trance as he follows the leaping Hobbes and the imaginative Calvin on their exquisitely painted adventure. My daughter Laura loves the occasional bits of dry, adult humor. Marlena likes how quickly she can advance through the books and how crazy Calvin is. And Haddie…well, she hasn't discovered the wonders of Watterson yet, but I'm confident that if I plant a book in her room a few more times it'll happen.

In short, my children just love Calvin and Hobbes; and, I couldn't be happier.

But as I've seen my kids adding delight-driven wear and tear to these volumes, it's gotten me thinking about how insightful Bill Watterson's work and career are for me as an educator.

Children are a cosmos

I've written before about how teaching a class is like giving a guided tour through a cosmos. That word cosmos means an order:

Your classroom is an alternate world from the one your students normally inhabit. Or at least, it should be.

It’s a cosmos—Latinized from the Greek kosmos: a good order, an orderly arrangement; a world.

Whether you teach art or agriculture, social studies or Scripture, English language arts or personal finance, you are, day by day, through helping your students toward mastery of your discipline, inviting them into a cosmos.

And that, of course, means a bit of discomfort. It means work. It means sacrifice and movement. It means sometimes doing things that, at least initially, will make you make “Urrrghghgh!” noises.

from The Will to Learn, p. 102

But when you read Calvin and Hobbes, a related truth emerges: our kids are a cosmos, too.

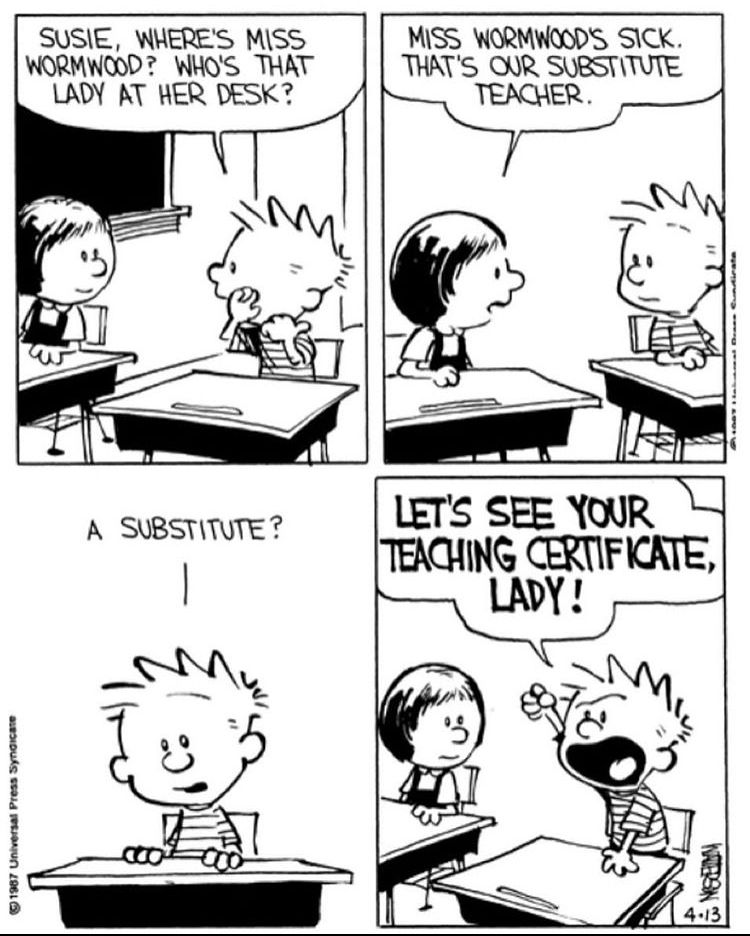

All teachers have seen at least a strip or two of Calvin sitting in Miss Wormwood's class, perennially stuck in first grade.

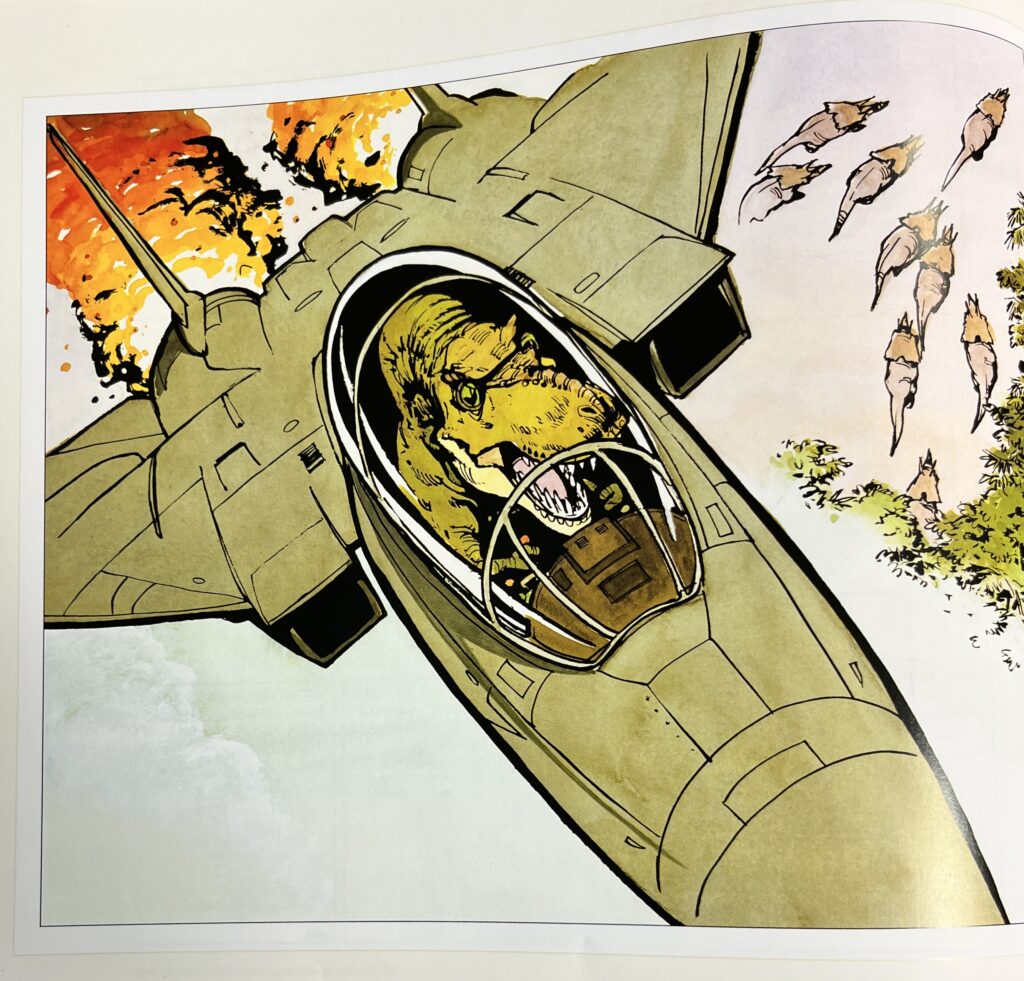

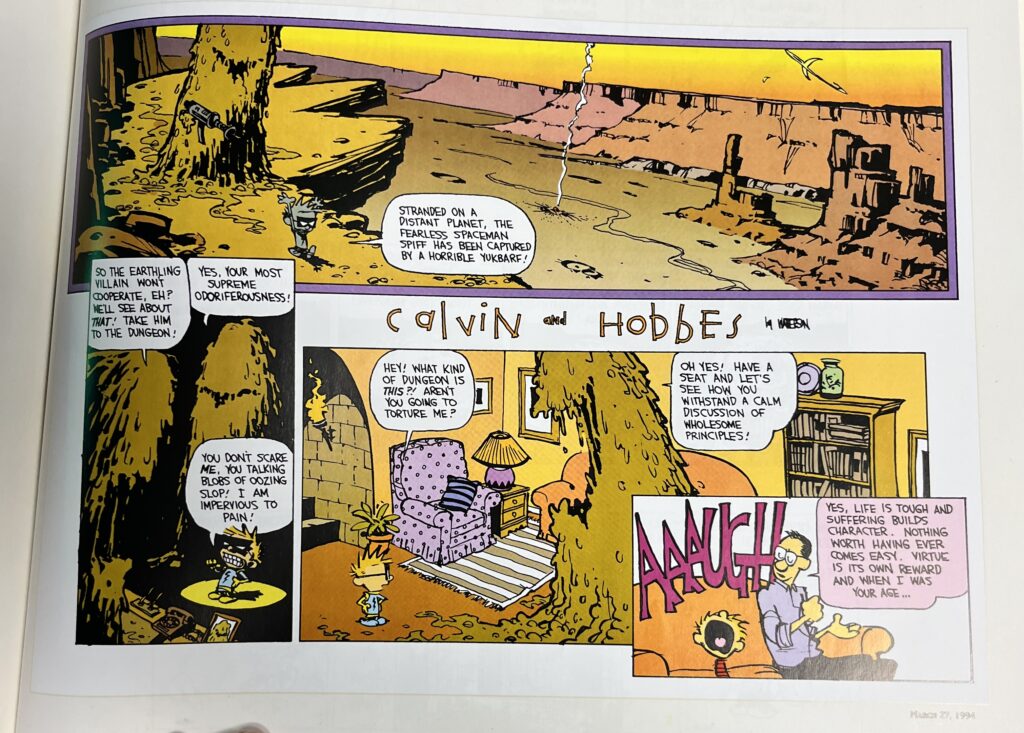

But as you read the rest of the strip, you also see Calvin's worlds of imagination. His Spaceman Spiff adventures. His noir detective stories. The transmogrifier. The G.R.O.S.S. club he and Hobbes run.

It turns out Calvin's a lot more than a first grade mischief-maker. He's a cosmos. What his teacher sees is only a sliver of who he is.

That's true of our students, too. The ones on our rosters, right now — behind each set of eyes there lies a cosmos.

Relish a bit of mischief.

But of course, no matter how delightful we find the many non-school sides of Calvin, there's no whitewashing the fact that, in class, he's a bonafide mischief-maker.

In rereading Watterson's strip, I find in myself a growing capacity for relishing a bit of the mischief some of my students bring to class, too. This doesn't mean I allow unchecked shenanigans to derail my lessons. It just means that, when I catch Susan making another zany face across the classroom to her friend, or when Jerome comes in to class today armed with his one zillionth argument for why he needs to sit by Dylan, I can sense in my heart a steady warmth for the full humanity these young mischief-makers bring to my room.

Watterson pursued an excellence all his own.

What brings me back to Calvin and Hobbes as an adult isn't just the insights into human nature, however. It's also, very much so, the exquisite art.

When you flip through the collection and see all the full-color spreads Watterson created, the craftsmanship on display can make your draw drop.

For instance, Watterson's exquisitely rendered nature scenes.

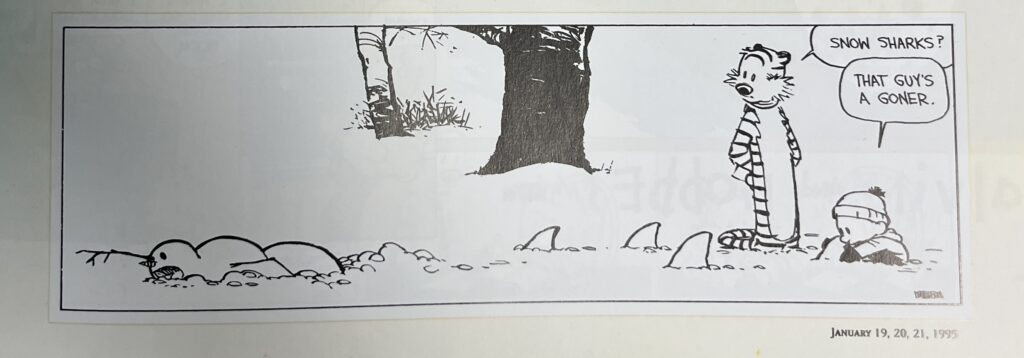

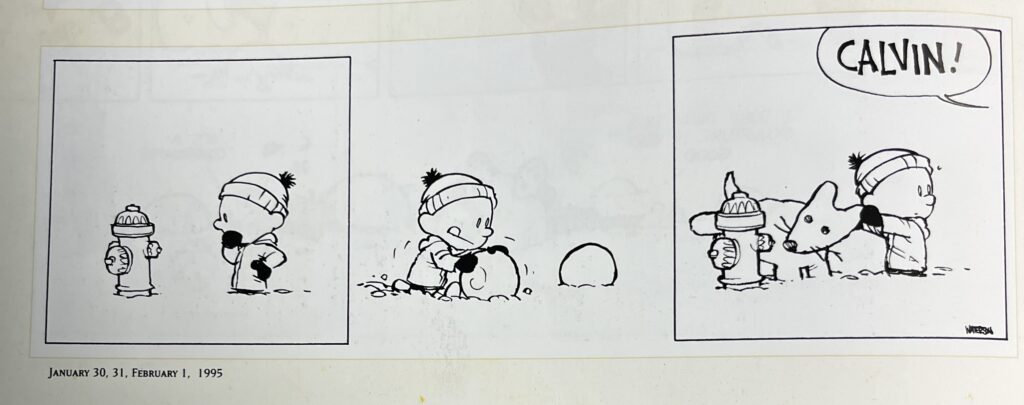

Or how about those maniacally expressive snow men?

Or the one where Calvin's pretending to be a dinosaur.

Or Calvin's cataclysmic front door greetings after a day of school.

Watterson was not just insightful — he was an artist, and he lavished his excellence at a level uncalled for by his medium.

I think the same is true for us. Do we need to be smart? Yes. Do we need to work within the (sometimes suffocating) constraints of school schedules and grading periods, just as Watterson needed to accept page sizes and deadlines? We do.

But colleague — we also need to be artists. The business of exploring mathematics and literature and art and health — this business of cosmos exploration — needn't match the dull blacks and grays that schools can tend towards.

Watterson's interests were wide and varied, and he found ways to bring them in to his work.

The strip's premise — the life of a first-grade boy with an imaginary best friend tiger — didn't necessitate the worlds of adventure Watterson takes us on. He didn't need to explore foreign planets such as Spiff or turn cardboard boxes in to Transmogrifying Machines.

And so, too, with our classes. Do we have curricula we need to teach? Of course. That's the job. Our students deserve knowledge-rich experiences across the disciplines.

But there's also space, should we choose to seek it, for us to share with our students the eccentricities and interests that make us us.

And in so doing, we become the best teachers we can be, teachers who are fully us.

Only Bill Watterson could make a strip like Calvin and Hobbes. And only you can make a class like yours.

Watterson knew when to say no.

If you've ever seen a bumper sticker of Calvin urinating on something, you can be sure that it's a copyright infringement. Why? Because once the strip began to see success, Watterson was diligent in saying “no” to bigger and better opportunities. In fact, during a rare public speech entitled “Some Thoughts on the Real World by One Who Glimpsed It and Fled,” Watterson implies that the hardest thing about his career was protecting his strip from the commercialization its popularity seemed to demand.

Should there be a TV show? He got the offer, but he declined. He said giving an actor's voice to Calvin would ruin the voice his readers already had in their minds.

Should there be merchandise? He spent years arguing with his publisher about this. In the end, Watterson won these arguments. He didn't want to add merchandising to his plate because he knew he did not have the capacity to ensure that such merchandise would keep with the spirit of the strip.

Watterson was something rare in today's world: a human being in touch with their finitude. He had only so much time, so much energy. He wanted to keep these precious resources focused on where he could do his greatest good — on his comic strip.

Watterson knew when to quit.

Finally, Watterson knew when it was time to be done. In this way, he reminds me of something career educator Jim Burke said in our interview when describing his decision to retire. It's a line from his previous principal that goes something like this: “It's always better to leave when you're not sure that you should than to stay around until everyone's sure that you should.”

In the interview Burke expanded on this, saying, “I wanted to leave while I still loved it.”

(Jim's full answer regarding how he decided to retire is here; the link will take you right to that portion of the interview.)

Watterson described a similar thought process when announcing his retirement to his editor.

Dear Editor:

I will be stopping Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This was not a recent or an easy decision, and I leave with some sadness. My interests have shifted however, and I believe I've done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises. I have not yet decided on future projects, but my relationship with Universal Press Syndicate will continue.

That so many newspapers would carry Calvin and Hobbes is an honor I'll long be proud of, and I've greatly appreciated your support and indulgence over the last decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity.

As I've said recently, there will come a time for all of us when quitting is the wisest thing to do. In both Jim Burke and Bill Watterson, I'm inspired by the idea that quitting can be done well and with wisdom.

Conclusion

Is Bill Watterson's The Complete Calvin and Hobbes the best book ever for educators? It just may be.

But mostly, that's because in reading it, you'll enjoy yourself immensely.

And also, it's an *amazing* gift for your kids, your loved ones, or yourself.

Best,

DSJR

Scott Leverentz says

Thanks for this message, Dave!

I feel like this echoes something that I’ve felt deep in me for a long time but never would have fathomed to attempt to put the words to.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Much love, Scott.

Drew says

Dave, this is so good. You’re on fire!

Carmen Munnelly says

BROTHER DAVE!

This Thanksgiving message from you obviously took time to craft, but I can only imagine your enjoyment and challenge in choosing which strips to include to both illustrate your point and Watterson’s imagination and mastery. It shows YOUR imagination and mastery. I really appreciate this! And now I know what ot get at least one of my grown nephews for Christmas.

Keep doing the hard and good work you do–until, like Watterson, you find you enjoy something more. “When I run, I feel God’s pleasure,” said Brother Eric, and I can only hope you feel the same about the work you do.

Blessings on the six of you!

Carmen in San Diego (currently a nice toasty 78°, to be a little Calvin about it)

Marci Scott says

Dear colleague,

Thank you for bringing to light that what brings me pure human joy in my teaching – that of the creative process that is all my own and inspires my students to be all their own!

Keep inspiring,

Marci Scott