“In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century's end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a fifteen-hour work week. There's every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn't happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more… The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. And yet virtually no one talks about it.”

David Graeber in Bullshit Jobs: The Rise of Pointless Work and What We Can Do About It, p. xv (paperback | audio)

“What does a person gain by all the toil at which they toil under the sun?”

Ecclesiastes 1:2

“[The speaker in Ecclesiastes] is carefully laying the foundations for the main argument of his book: only preparing to die will teach us how to live.”

David Gibson, Living Life Backward: How Ecclesiastes Teaches Us to Live in Light of the End, p. 28 (paperback)

Every year, the tasks that come with being a teacher grow in number. There's more to do, more to learn, and more to be aware of. There are more students or more needs or more challenges. I say this not from a pessimistic or cynical standpoint; to me, it's like saying, “The sky is blue,” or “Water's wet.” It's just the reality of being a teacher in the twenty-first century — and, as David Graeber points out, this reality of increasing workloads isn't something teachers have a monopoly on.

So my take on this is this: there's not much good in being mad at reality.

But at the same time, not all the tasks on my list are equal in usefulness. Not all the tasks are closely linked to advancing the long-term flourishing of my students by means of guiding them toward greater mastery of reading, writing, speaking, listening, and thinking in the disciplines I teach.

So how do we grapple with this?

We can go about this in one of two ways. The first way is tidier and has less accidents, but it's super slow. The second way is messier and has more accidents, but it's quicker. (I prefer the second way because the accidents in speeding up this process are minor and the benefits are enormous.)

The First Way

- Write down a list of all the tasks that you complete in a given week. Don't do it theoretically. Do it as it actually is happening. Write a list of all the things you're expected to get done as a teacher for the next week of your life.

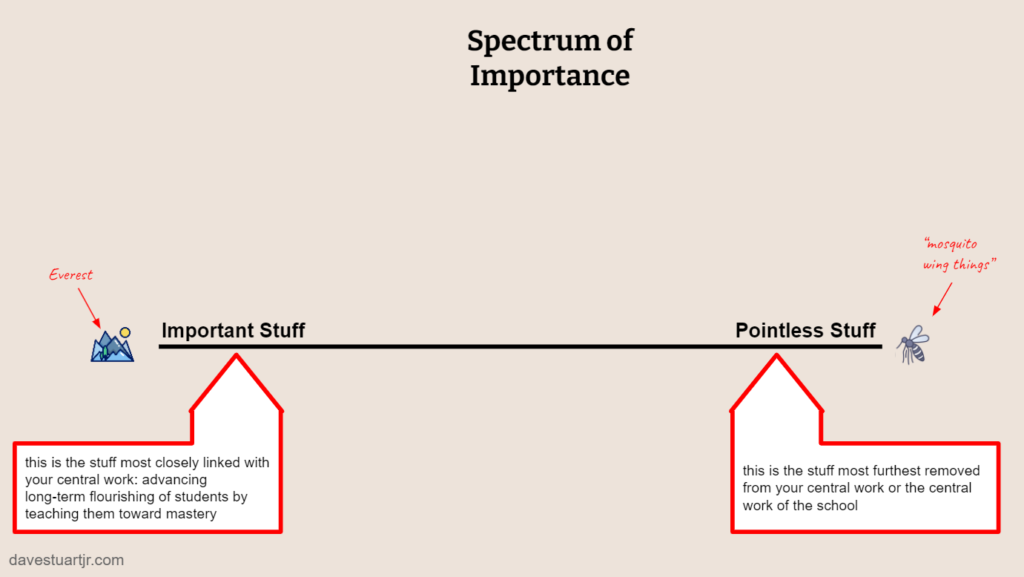

- Then, place the list on a spectrum of importance — something like this:

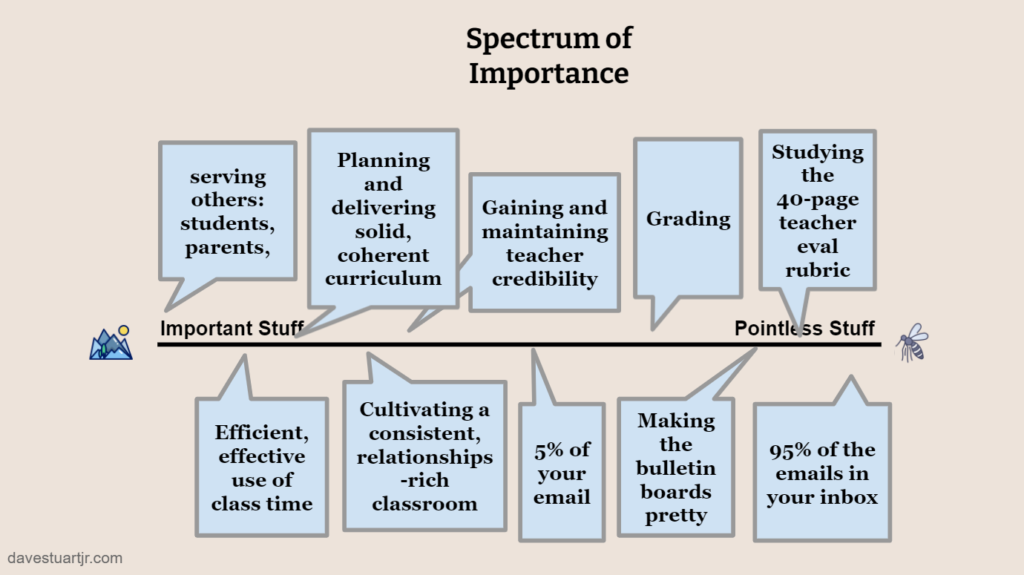

Here's a sample I made one time:

- Finally, begin experimenting with ways to speed up or avoid the stuff furthest on the right. I'm not recommending blinding irresponsibility, but I am recommending intentional irresponsibility.1 Some things are not worth being hyper-conscientious about.

The Second Way

The trouble with the first way is that it'll be easy to keep tricking yourself into spending too much time on the pointless things. If you've been a super-conscientious, details-oriented person your whole adult life, you won't be able to think your way to being quicker and (dare I say) sloppier with the things that aren't closely linked with the long-term good of your students or the success of your career. In other words, you'll be a slow study at satisficing — completing less important tasks at the lowest acceptable level rather than the optimal level.

The second way is to create simple rules that CONSTRAIN2 the total number of hours you are able to work each week. Here's one way to do it:

- First, estimate the total number of hours you currently spend working on teaching stuff — at work, at home, on the couch, in your email.

- Then, ask yourself this question: if I had to give more time to non-work stuff, what would that look like? Where would I cut first?

- From this line of questioning, create a few simple rules. (Here is where a close friend or spouse can be a helpful partner. They see some things that we're blind to. There's a pretty funny story about my now-wife opening my eyes like this right here.) Here are some examples that I've used in my own life:

- I work weekdays from as early as I want until 5:15 pm. I'm home and ready to be all-in with my outside-of-work life by 5:30 each night.

- If I'm going to work on the weekends, the only possible time is Saturday mornings before anyone wakes up or Sunday evenings after everyone's in bed.

- I don't allow email apps on my phone — for work, for personal, for anything.

- I don't respond to school-related calls or text messages after 5:00 pm each night or on weekends.

I don't use all these rules all the time. It depends on my course-load, my prep-load, and my responsibilities outside of the classroom. But (this is important) I remain heavily biased toward making the rules feel difficult. I treat it like a game — if I had to make teaching simpler, how would I do it? If I had to make running a single-person consultancy simpler, how would I do it? If I had to make creating articles and videos for teachers more efficient, how would I do it?

Please, hear that — I treat the constraints like a game. Even though I think teaching is the best and most important job I can imagine doing outside my home, I have no delusions about the criticality of my class. I'm one of many teachers for my students. I'm one of many influences. I want to make it a great experience for them. I want them to grow in mastery. I want them to deepen as people. But I also want to enjoy the process as I do it and enjoy the rest of my life, too.

So the second way = impose constraints with simple rules, remembering to smile as you learn.

A few things to keep in mind about this:

The path to proficiency is giving as much of our energy as possible to the competencies on the far left of our spectrum above. Getting awesome at answering and acting on questions like:

- How do I help all my students to care about the work of learning?

- How do I help all my students do the work of learning with increasing effectiveness?

- How do I work in my heart to love and appreciate all the people I work with: students, parents, colleagues, bosses?

- How do good lessons work? What are the basic components? How can I improve these without stressing myself out?

- What's the difference between grading and feedback? When should I do each? When should I do neither?

So much of getting better quickly comes down to asking the right questions.

You have to let small bad things happen for the second way to work. What I mean is that if you start limiting the hours you have to work, inevitably you're going to have a day where you piddled away the time or just didn't have enough of it, and you're going to get to the end of your work day and realize that you don't have tomorrow's lessons well-planned.

This is a key moment in the process. You have to still go home and still not work.

This will teach you:

- That lesson planning gets priority over about anything else;

- That simpler lesson templates (e.g., the nine moves for teaching with texts) that can be repeated are a better long-term bet than fancier one-off lessons;

- That you're not a complete nincompoop and can do some things in the classroom with less planning than you thought; BUUUUUUUUTTTTT

- That next time, you'll prioritize lesson planning first (I find that it's typically easiest right after class or school; I even sometimes jot down notes about fifth hour when my sixth hour students are doing their warm-up).

All right. I think that's enough to make ya dangerous. Now: go set some simple rules and have fun learning about the work that matters most!

The Stewarding Our Lives seminar is coming up — first cohort ever, going to be a lot of fun exploring these disciplines in-depth with colleagues near and far. Lots of live time with me, too — you can ask me anything, all seminar long. Details and waitlist here. Trailer below:

Footnote:

- Acclaimed physicist and teacher Richard Feynman once said this to one of his biographers: “To do real good physics work, you do need absolute solid lengths of time…it needs a lot of concentration…if you have a job administrating anything, you don’t have the time. So I have invented another myth for myself: that I’m irresponsible. I’m actively irresponsible. I tell everyone I don’t do anything. If anyone asks me to be on a committee for admissions, ‘no,’ I tell them: I’m irresponsible.” (Source)

- CONSTRAIN is the second discipline of

time managementlife stewardship that we'll examine in the Stewarding Our Lives seminar.

Leave a Reply