I was speaking with our colleague Tanya Ramm this morning, and she was describing her holiday weekend. (We had four days off for the US's Labor Day.) Over the break, she came in to work for five hours on Friday while her husband and sons were off fishing. Then she came in to work a few hours on Sunday in the morning time.

“And Dave,” she said, “I just had the absolute best weekend. It felt amazing.”

What my colleague illustrated for me is the reality that teacher time management isn't as simple as working certain hours or certain days. It's instead about living on purpose — doing X because we've decided to do X, doing Y because we've decided to do Y, because these things align with our values and the lives we want to look back upon when we're older.

As we continued to talk, Tanya shared that in the past year she's withdrawn from several commitments that used to bring a lot of extra complexity to her work: NHS sponsor, PLC leader, MTSS committee member. She did these things because she wanted to do her part; she wanted to be viewed as a dedicated member of the faculty.

But as her non-renewed commitments accumulated behind her, Tanya felt lighter and lighter. The pressure she had felt — to be seen as a certain kind of faculty member — diminished. In its place, she's found a renewed capacity to lean in to her first loves of wife, mom, classroom teacher, community member.

“I feel like a new person, Dave,” she said, all aglow. And she feels like she's a better teacher than she's been in a long time. And she's not working around the clock.

The most important practice of effective time managers life stewards

The reason I bring up this story is because it illustrates the power of the most important practice for time management: deciding.

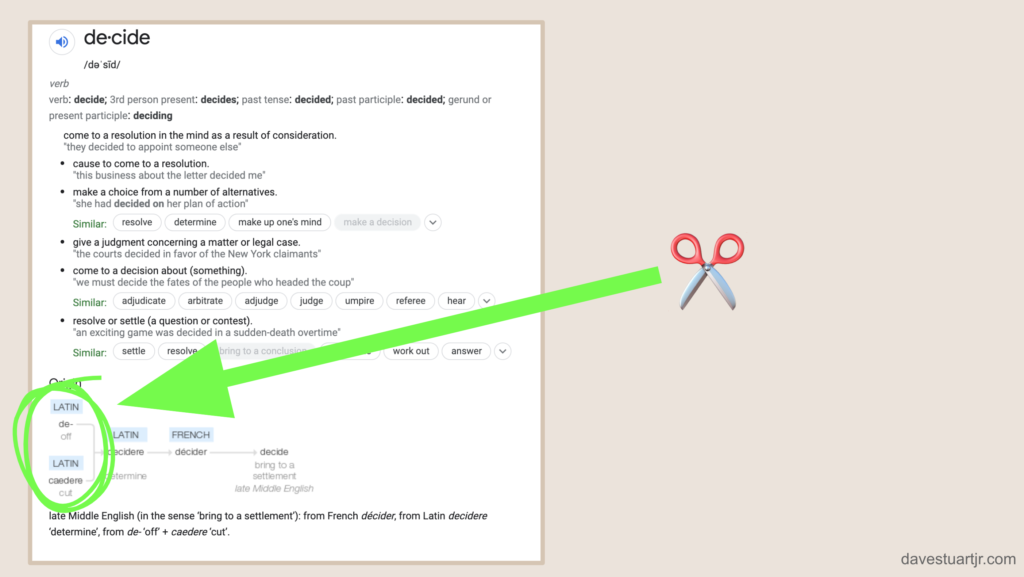

To decide is to cut off; to say, “This, not that.”

It's the “not that” part that we tend to have a hard time with. Instead, we trick ourselves into thinking there's a way to be alive and to say, “This… and that… and that, too!”

But try though we might, we come up against our limitation. We can't do it all. No one can.

And here's the good news: finitude isn't a bug of being a human — it's a feature. In our finitude, we find the fixings for a life of meaning. But in ignoring our finitude, we end up frazzled, harried, burnt out, grumpy. Our souls feel stretched out — and inescapably we teach and love from this stretched-ness.

When we try having it all, doing it all, being it all, we end up shadows.

This is why the first mini-project we'll complete in the Stewarding Our Lives Seminar is a Value Structure — an idea I gained from an old Matthew Kelly book, Off Balance: Getting Beyond the Work-Life Balance Myth to Personal and Professional Satisfaction. I love one of Kelly's central arguments in the book: that our aim shouldn't be a balance between work and life but rather a harmony.

It's that harmony, I think, that our colleague Tanya's story illustrates. It's not that she kept work a million miles from invading the holiday weekend. It's that she decided some things these past years that have enabled her to live — whether at work or at home — with a renewed sense of harmony.

May you and I get better this school year at deciding, colleague.

Best to you,

DSJR

Next month, for the first time I'll be leading a group of colleagues through the ten disciplines (or practices) of effective time management. I'm calling it the Stewarding Our Lives seminar, because to steward is to take care of something on behalf of others — our families, our students, our future selves. I think so much of life and education comes down to stewardship. I'm eager to explore these ideas in depth with colleagues in October.

All the details are here. Sign up for the waitlist if you're interested! Waitlist folks get first dibs when registration opens in a week.

Boyd says

You’re on to something here, DSJ. The need to have a true sense of self. To ask myself if I’m meeting my expectations, or someone else’s. And if I am meeting someone else’s expectations, it is because I have chosen to, which, in turn, makes them my expectations. My sense of identity is true when the locus of control is within me and does not reside with someone else.

A quote on my office wall by Anna Quindlen reflects this same sense of purpose.

“Begin with that most frightening of all things, a clean slate. And then look, every day, at the choices you are making, and when you ask yourself why you are making them, find this answer: Because they are what I want, or wish for. Because they reflect who I am.”