Note from Dave: When I began my career in 2006, it was as a sixth grade English Language Arts teacher in Baltimore, MD. I can still remember the scripted curriculum they handed me, complete with workbooks, student consumables, and the expectation that all of my students would be working on decoding phonemes in my double-period, sixth grade English language arts class. Mind you, I was teaching the students identified by the state’s reading and writing measurements as low-performing — but, of course, there was a wide range of aptitude, interest, and gifting in those groups of kids. As you can imagine, none of them enjoyed the scripted, “Let’s write two-word sentences for a month” curriculum — and their teacher didn’t either!

My principals were great, and they understood all of this. They quickly gave me the flexibility to teach outside of the script, giving me permission to do what I thought was best. But this presented a whole different problem: How was I to teach my students how to write effectively — both in response to the high stakes writing questions that were coming their way in the spring and in response to a broader range of writing tasks that would be facing them in the years to come? If only I had access then to Lindsay Veitch’s simple, explicit method for teaching students how to write coherently across the content areas.

Lindsay told me about The Write Structure about half a year ago, and I was immediately impressed by both the results she was seeing her students achieve and how her colleagues at the middle school where she works had begun successfully using the strategy as well. Effective? Check. Low-stress enough to lure a colleague into wanting to try it? Check.

And here's what I think we can all learn from what Lindsay writes about in the post below, whether we teach ELA or not:

- She dug into a problem that had been bothering her. In this case, taking the stress, confusion, and mystery out of effectively responding to the myriad prompts our students experience in a given school year.

- She happened upon something that worked, and then she continued to hone that method. She focused on what was working and mastered it, rather than moving on to the next thing.

- Repetition makes it stick. Lindsay's students use The Write Structure over 50 times in a school year; it becomes a part of their brains.

- A broad array of in-class applications (plus a healthy dose of fun) makes it memorable and meaningful enough to transfer. This isn't drill and kill. Because Lindsay uses The Write Structure as the core of her writing instruction, students apply it to prompts across her ELA and social studies units. This develops a deep understanding of the model that transfers to situations outside of her classroom, be they high stakes tests or writing prompts in different courses.

And so it is that six months after Lindsay wrote me, I am so proud to introduce her brand new guide, The Write Structure: A Simple, Effective Method for Teaching Writing Across the Content Areas, which I think makes memorable and explicit some of the central moves our students need for effectively responding to writing prompts.

I am so grateful and excited to introduce to you my friend, Lindsay Veitch. Below, please enjoy her introduction to her new book.

The Write Structure: A Simple, Effective Method for Teaching Writing Across the Content Areas

I know this scene is familiar to you: A student absently stares, struggling to form sentences for a science writing prompt; a soft chorus of sighs and moans bubble up from the class when a text response is assigned; sets of glossed over eyes glare at the blank text box on the State Test; a teacher so much as utters the words Constructed Response, and students start melting in their seats. These kids aren’t alone; many otherwise bright and successful students (and adults for that matter) loathe writing tasks. It is the number one thing kids tell me they don’t feel successful at in school. Yet it is the number one task we charge kids with at all grade levels. I believe writers struggle to write not because they can’t write, but because they don’t know how to format their thoughts, which makes them feel like they can’t.

State test prompts are ever-changing. The types of writing — expository, argumentative, compare/contrast, constructed responses, and so on — overwhelm our kids. It’s ACT one year and SAT the next. Further, writing formats are, literally, a moving target. If a kid got a dollar for every new concept map, random outline, and graphic organizer he or she was given in the course of a K-12 education… you get the point. There are millions of writing outlines out there and tons of formats teachers could and do use to teach writing. Many of them are good, research-based, and effective. But truly, the whole of it is overwhelming. It’s hard to imagine masses of 14-year-olds remembering to say thank you, let alone remembering the 107 different outlines and concept maps from the past eight years of school.

Even after teaching ELA for over a decade and attending plenty of motivating and helpful professional developments, I struggled to find a simple and straightforward way to teach kids to write in ELA and across content areas. We are all professionals — able writers ourselves — yet we feel ill-equipped to teach writing. People shy away from the teaching of writing because it feels so messy and complicated. Still, we tell kids to write all the time, literally dozens of times a day. They write right in front of us and alone at home. Too often, though, students aren’t shown how to write. Further, students have told me that they want a simple, consistent structure to follow. Like in math, they say, something black and white. Their point became loud and clear, and I wanted to make writing easier for my kids. Many teachers like me feel the same way, and we try to help by supplying kids with concept maps, outlines, and more. What ends up happening, year after year, is an ever-changing set of writing rules and methodologies are presented for kids to follow. Moments of success one year are replaced by confusion and frustration the next.

I realized that what I needed was a writing method that would stick in the already-overwhelmed minds of the students I stand in front of and sit beside each day. What my kids needed was a simple structure that could be applied to any question, prompt, essay, or blank text box. This structure needed to be memorable. It needed to help enrich writing. It needed to be applicable anywhere. A first grade piece about summer vacation, a fourth grader writing about a social studies topic, a ninth grader developing an argumentative essay about invasive species in the Great Lakes. Adults in college writing emails, drafting speeches. I looked for this format and found many options: writing acronyms galore, expensive trainings, and a lot of homemade outlines. I found ample concept maps, most of which are free. None of these options felt totally transferable. None of them stuck with my kids. I couldn’t make them work in the dozens upon dozens of writing tasks I assign my kids yearly. But one day, I stood in front of my class, especially amped up on coffee, and waved my hand in the air telling my students to “IDENTIFY IT!” (On that day, the “it” was the theme of a text we just read). Next, I pointed straight ahead and shouted, “Then you have to PROVE IT!” (with evidence from the text). And finally, because I was on a roll, arms flailing and pointing with such passion, I said, while swooping my hand back to the original motion, “BRING IT BACK AROUND!” (explain how your quote proves the theme and then rephrase/restate your theme).

And there it is. The method I’d been searching for was born. We started using this language to develop and structure paragraphs about theme, then author’s craft, then constructed response in history class to format sub-topics for informational essay paragraphs, even for developing speeches.

The Write Structure is not foolproof. It takes work and a lot of recycling. In fact, like all good ideas, it’s effectiveness still hinges on how it’s modeled by the teacher, how it’s retaught in conferencing with kids, how it is applied across content areas. I have proof that this method works. I’ve seen all kinds of students turn a blank piece of paper for their State Test into an outline — where Identify It! Prove It! Bring It Back Around! (which my teaching partner, Jenn, abbreviated to BIBA — pronounced “beeba” — it’s so fun to say!) guides their thinking and writing. The quality of writing students produce and the scores they earn prove it. Most importantly, The Write Structure takes the guesswork out of kids’ biggest question: How do I write this? Blank paper or an empty text box no longer signals the chorus of sighs and moans. Anxiety is lowered. Students embrace the prompt because now they know how to think about writing.

This method is the very core of writing instruction in my classroom. It has become the starting point for every expository (informational) and argumentative writing task my kids assume. I begin the school year introducing and modeling how to apply the structure with a thoughtful, rich Dr. Seuss text, The Lorax. (See Figure 1.) First, I teach the lively hand motions I made up on a whim the day the method fell of out my mouth. It goes like this: they stand, sometimes on chairs (scandalous, I know) and scream it as loud as they can. “IDENTIFY IT! PROVE IT! BRING IT BACK AROUND!” Other classes hear us and create alternates to Bring it Back Around — the original alternate being “NEVER TRIP A CLOWN” (which they shout back at us through the walls and down the hallway). This one comes from the classroom of our fun and cheeky math teacher — who, by the way, courageously started using the method to reinforce writing in math class. Amazing. Even the middle schoolers who are too-cool-for-school participate in the hand motions and shouting matches. They remember the method. It sticks.

I model and guide writing instruction around theme and author’s craft using our first anchor texts, The Lorax and then Salvador Late or Early by Sandra Cisneros. Days later, students draft their first speech of the year, a personal speech about meaningful events in their lives. The method is useful in helping them Identify the lesson from the event, Prove It with the story of the event, and Bring It Back Around by explaining/restating the lesson.

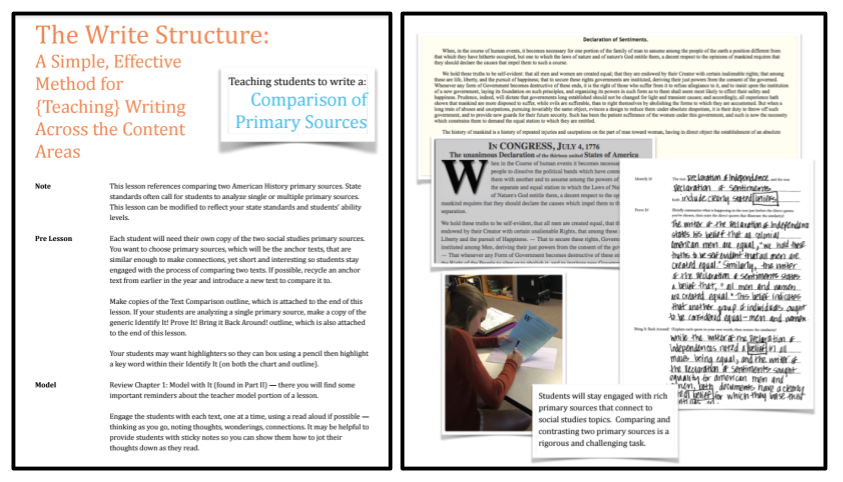

From there, the structure is recycled with a research chart in preparation for a big informational essay, in the development of a class debate and argumentative essay, and visited again in constructed responses about how a theme changes throughout a text. In science class, it’s used in an outline for an argumentative essay on volcanoes. In math, it’s modeled and used as a way to Identify a word problem answer, Prove It with numerical evidence/justification, and Bring It Back Around by restating/explaining the answer.

Students are asked to recall and implement this structure no less than 50 times in a year throughout the different content areas, but mostly in English Language Arts. They know the hand motions, they know what the method means, so when April rolls around and it’s time for the State Test, they are like, “Oh yeah, I can write about whatever they throw at me!”

And they do. It’s remarkable. (See Figure 2.)

The Write Structure sticks because I am determined to slide it into every single reading, writing, and speech assignment. It’s so simple and obvious, but the kids don’t get sick of it. In fact, I think the method brings a sense of relief. When they see the wording — Identify It! Prove It! Bring It Back Around! — on an outline or a speech brainstorming map, confidence is built. It’s written into every single writing task, every single text response, and every single speech.

This method also works because people “who aren’t ELA teachers” become willing to teach “ELA stuff” when they see how simple and effective it is. It’s very easy to move over into science and social studies where expository writing is happening all the time. In math, students are given writing tasks, usually small ones, and this method works beautifully. Some students may roll their eyes at the math teacher who breaks out the hand motions… but don’t be fooled. THEY LOVE IT!

Finally, writing is scored based on The Write Structure. Our rubrics and scoring guides hold kids accountable to each of the parts. We write samples together as a class and many times use the rubrics or scoring guides to range find, the process of analyzing and scoring work together as a class. We use the rubrics to guide conferencing about writing, and having this language makes conferencing all the more effective. If I sit down and tell a kid I’m going to help him or her develop a richer “BIBA,” they know exactly what I mean. And this makes the whole process smooth, quick, and effective.

But of course, there are no silver bullets, and this method is no exception. If this method were a requirement on every ELA writing task a kid was given and on every outline they’re assigned with no modeling (see Figure 3) and no conferencing, it would be less effective. If science, social studies, art, math, physical education teachers all embraced the method and put it on their handouts, but didn’t model and review The Write Structure, students may become numb to it. If this method were put on a poster and hung in every classroom across America but no one wrote it out along with and for the kids, it would fall flat.

For The Write Structure to be successful and enrich students’ writing, the following things cannot be avoided or skipped:

- Model how to write with it over and over and over.

- Conference with kids when they’re practicing on their own.

- Do the hand motions and make them fun!

- Share your successes with every teaching partner you have so they can become excited and transfer it into their classrooms.

- Show kids how to use it when there is no outline provided, when they are faced with just a question/prompt.

- Celebrate when you see kids doing just that — using it when there is no outline provided, when they are faced with just a question/prompt.

- Use the method to score kids writing by marrying outlines and rubrics with the format and language.

- Score sample writing pieces together, using those very rubrics — pointing out and critiquing the key parts — asking the kids: Where did the writer IDENTIFY IT? Where did they PROVE IT? Find the BRING IT BACK AROUND (BIBA) and make sure it’s thorough and well written.

- Once you see it working, weave it into every writing, text response, and speech you teach and assign.

(These form the nine Key Practice chapters in Part II of the book.)

Writing know-how is a skill set that this generation of students desperately needs. There are no shortages of professional jobs and life events wherein a structured, cohesive, well written, rich piece of writing is required. This method can be internalized and embedded in the thinking of all students. It can stick. It will make a difference. It will be the way grown up students and adults think about crafting emails, summative college exam essays, speeches, business propositions, plans. Let’s help take the guesswork out of good writing and set kids up for success.

Michele says

I bought this and am excited about it! You and your colleagues are bringing us great things, Dave. Thank you again!