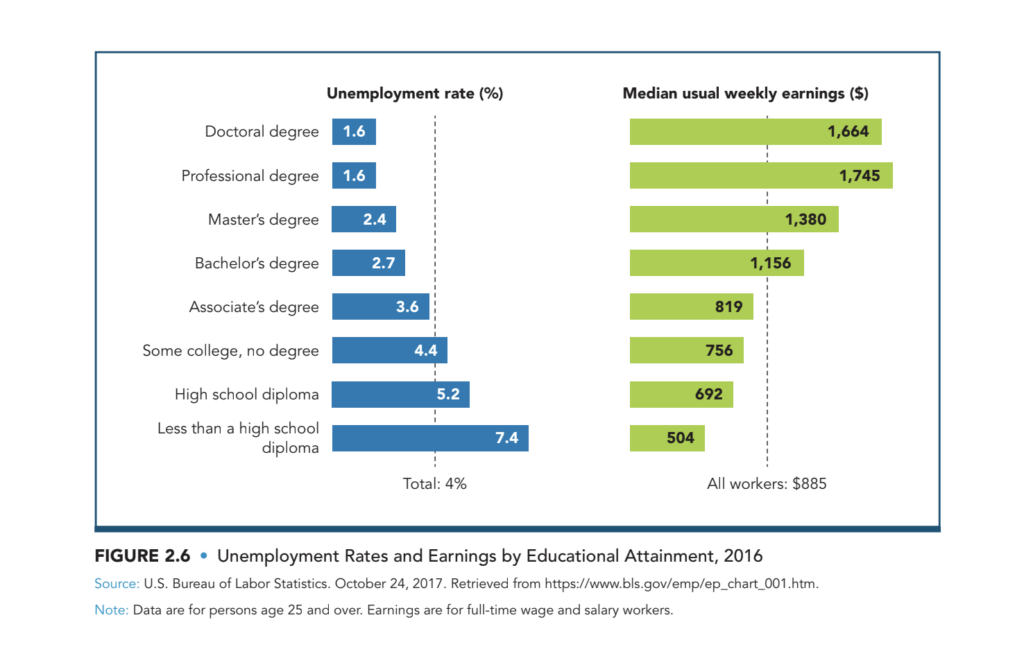

Earlier in my teaching career, I would try to help my students value the work of learning by showing how educational attainment related to long-term earnings. In These 6 Things, I've even got a picture of the chart that used to hang on my wall before they renovated my classroom and tore the wall down.

(Image is from p. 55 of These 6 Things.)

When I was setting my classroom back up, I decided to no longer hang this sign. Part of the reason I don't want it up anymore is that it doesn't show the full economic picture of higher education. (Nowadays, you've really got to weigh expected earnings with expected costs, which this article does a great job explaining.)

But I've kept the poster down for a more fundamental reason. And the reason is this: human beings are bad temporal reasoners. In one of my favorite papers on the Value belief, Bryan et al. put it this way:

People discount the value of temporally distant rewards to an extreme and irrational degree.

Bryan, C., Yeager, D., Hinojosa, C., Chabot, A., Bergen, H., Kawamura, M.,

& Steubing, F. (2016). Harnessing adolescent values to motivate healthier

eating. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(39), 10830–10835.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.1604586113

Now notice that the researchers here aren't targeting just our students. They're targeting all of us. But based on my experiences as a parent and a teacher, I'd like to suggest that students are especially prone to discounting the value of temporally distant rewards.

This is why I basically never make arguments to my students about what they'll need in the “real world.”

- First of all, this is disparaging toward both school and student lives. Do I really want to parrot that school isn't real? Do I really want to suggest that my students aren't living in reality? For me: no. I do not want to do those things.

- And second, it's referencing something that is temporally distant. In the aforementioned paper, Bryan et al. argue that this is not a great plan.

Thankfully, the researchers of that paper do much better than making a claim — they demonstrate its veracity with an interesting study.

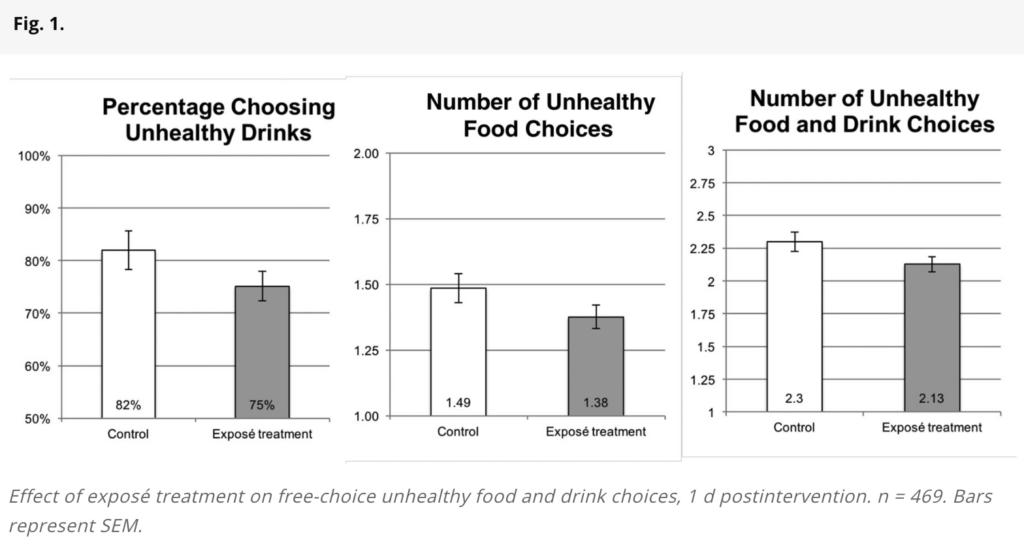

The researchers took 536 eighth grade students and split them into two groups:

- Group A was taught that unhealthy food is bad for your future health.

- Group B was taught about the manipulative and unfair practices of the food industry (e.g., engineering junk food to be addictive and marketing it to young children).

The next day in an unrelated context, researchers observed the food and drink choices of the study participants.

Basically, students weren't as motivated by the temporally distant rewards of healthy eating (e.g., better health as an adult) as they were by the temporally proximate reward of doing their part to “stick it to the man” and resist the food industry.

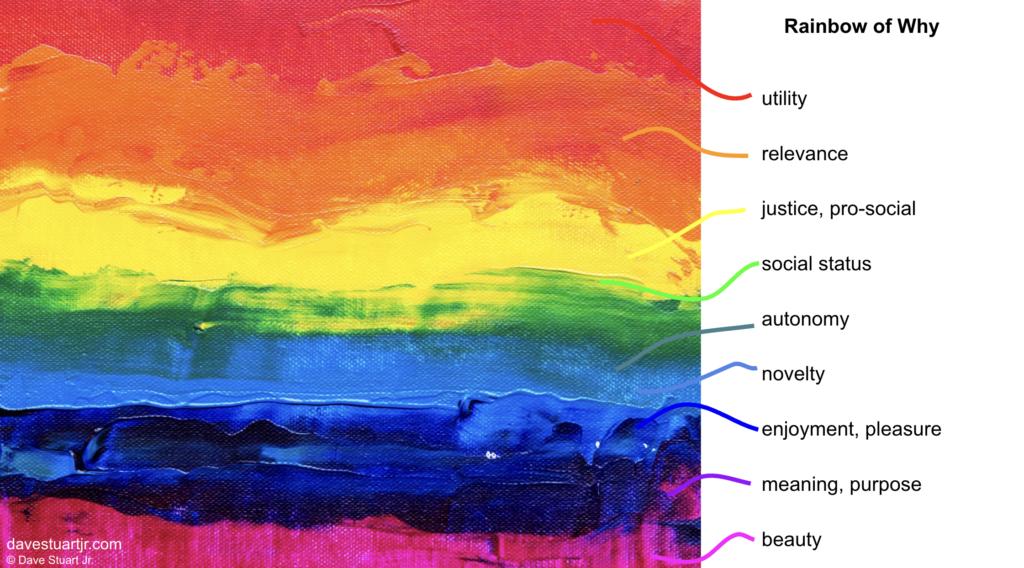

At this point, it's helpful to bring this all together with the Rainbow of Why.

(The Rainbow of Why is explained in the Value section of my new book, The Will to Learn.)

So basically:

- Temporally distant claims (e.g., “You'll use this in the real world;” “You'll need this someday”) are plays at utility, and they have limited power, in part because humans are bad at temporal wisdom and in part because utility is way overused in school.

- Whereas what the researchers did for Group B angled at things like autonomy — students were given information but not told what they should do — and justice — in this case, by highlighting the injustices of some junk food industry practices.

All of which is to say, keep your Value approach spread across the color spectrum.

It'll work much better.

Best,

DSJR

Leave a Reply