Teaching can pretty quickly turn you into a basket case. Consider a list of responsibilities — of things that we “have to do” — that our colleague Lynsay Fabio, a secondary English teacher, came up with recently.

(Note: A potential side effect of reading this list is shortness of breath.)

- Read the class novel myself, or write the anchor paper myself, so that I can understand the struggles my students might encounter when it’s their turn

- Plan lessons

- Write mastery responses (i.e., exemplars) or find them from last year

- Create materials

- Copy and print materials

- Differentiate materials for students who receive accommodations and modifications

- Execute a solid lesson, five times per day

- Check for understanding, unveil student misconceptions, and react quickly enough to redirect them to mastery

- Give feedback on oral, in-class responses

- Provide extra, in-class support for students who have accommodations and modifications

- Collect data and use it to modify instruction, both short- and long-term

- Execute a classroom management plan and keep records

- Maintain a system for effectively managing the torrential paper-flow

- Monitor students’ behavior and conversations in the halls at the change of classes — five times per day

- Take attendance by X time and input it following my school’s specific protocol

- Maintain a neat and orderly classroom and teacher desk

- Hold extra help or office hours after school

- Give written feedback on writing assignments

- Grade major and minor assignments

- Maintain a fair, plentiful, and current gradebook

- Remain up to date on current grade-level standards, as well as students’ current levels of performance, and modify lessons and assignments accordingly

- Remain aware of the pacing of our lessons versus the ideal pacing of the unit as written, and the academic calendar, and oh wait, isn’t there a break coming up? So sh*t, I guess that paper has to be due THIS week

- Update lesson plans, units, and curriculum to reflect the learnings of this year’s instruction

- Attend staff and coaching meetings on time with an open mind

- Attend IEP and behavioral concern meetings with documentation, ideas, and feedback

- Monitor students’ behavior and conversations in the cafeteria, library, or other common spaces to promote positive school culture and shut down bullying

- Have conversations with each student we teach to build one-on-one relationships

- Call home for both positives and concerns

- Attend in-service for common struggles of adolescence (e.g., suicide and mandated reporting), maintain these warning signs in the back of our minds, and act accordingly should the awful moment arrive where a student seems at risk

- Promote our own professional development, including but not limited to observing master teachers’ classes, filming our own classroom and watching the footage, attending coaching meetings, outside reading (like These 6 Things), outside classes (like the Student Motivation Course), and homework for PLC.

- Build and maintain a classroom library that, in cleanliness and abundance, reflects the deep respect we have for literature and for our students

- Achieve X result on Y standardized test

- Implement Z whole-school reading/writing/vocabulary/character/rubric initiative

- Field questions from students and parents outside of school hours

Obviously, this is a devastating list — devastating because it's familiar and real and authentic, and devastating because it sets us up for impossible frustration. Consider that many who enter teaching tend to be task-oriented, to-do list types with tendencies toward perfectionism. Add to that the life-and-death weight that teaching automatically carries — the way that the work any day in any lesson can have an impact on human lives and long-term flourishing outcomes. And then throw atop the pile that teachers in high-performing international systems (as measured by PISA) tend to have markedly fewer instructional hours per year (i.e., more planning time) than their American peers. [1]

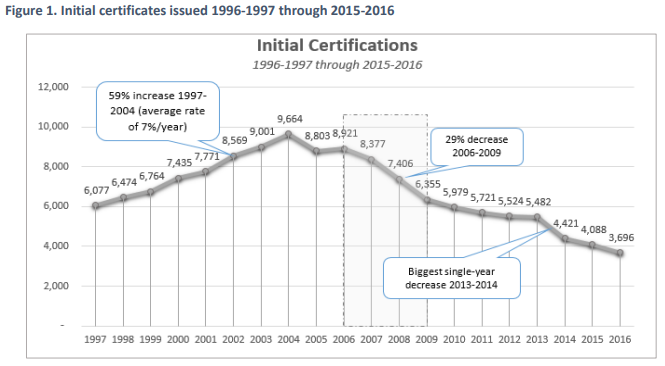

The mental picture I'm left with is of a drowning person, who in response to their drowning is thrown several bowling balls. It is no wonder that fewer people are drawn to education these days (below, a graph depicting the decline of teaching certificates in my state). Why would I want to enter a line of work that appears to suck the souls right out of teachers?

Because teaching is good and the list isn't fixed

The good news is that even though teaching does suck the souls out of many who enter the field, it doesn't have to. Certainly, we've got some messed up policies in the USA, and we've got some detached bureaucrats ensuring compliance rather than solving problems, and there are states and systems that practically write, “We devalue teachers,” on giant billboards along the highway.

The thing is, though, none of these hard conditions make teaching any less noble. It still boils down to investing in the lives of young people, seeking to challenge them and guide them and teach them cool things like physics and physical education and Romeo and Juliet and business and math. It's still a super cool thing — always has been, always will be. And so if you believe that, then you're like me: I'm sold out on the goodness of teaching, but I refuse to let it suck out my soul. I refuse to act under a list like the one at the start of this post. Why? Because it's an impossible list, and not every item on it is created equal.

And so that becomes a part of the work in systems where the pressure is insanely high. We set constraints, we force space for thinking, we start practicing the precious arts of satisficing and intentional neglect.

At the end of the day, we live where we live (unless we move) and we teach where we teach (unless we make a change). So, once we're here, no one is going to give us more time, and probably no one is going to come and tell us what we should stop doing so that the list is doable.

In this case, it's simple and hard at the same time: we've just got to decide.

If you'd like to dive deeply into how to grow in teacher wisdom — how to make good decisions and put the list in perspective and develop resilience and joy for the work — consider the all-online, schedule-friendly PD I'm making. Here's the waitlist. Details go first to the folks on the list.

Footnotes:

- According to two sources, Finnish teachers have 600 instructional hours per year on average while American teachers have 1,100. (The first source is Tony Wagner and Ted Dintersmith's Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era, and the second is this article at Virgin.com.) I'm not a math guy, but I do know that 600 < 1100. [2]

- For two more high quality, nuanced references on international teaching comparisons, consider Marc Tucker's (now retired) blog and Tim Walker's book Teach Like Finland: 33 Simple Strategies for Joyful Classrooms and vlog. Both steer well clear of simple-minded comparison or trite conclusion.

loudenclearblog says

You know, it makes sense that the most read post on my blog is “3 Things Teachers Can Learn from a Mental Breakdown”. That just tells you how many teachers are googling “mental breakdown + teacher”. So sad. This list makes me cringe because it is just so darn accurate. Add to this list what other duties teachers are assigned and/or clubs/groups they sponsor. Sheesh.

davestuartjr says

So true, Kristy. Within these conditions, we have to find a way to be free and focused. Much love to you and your colleagues there in Alabama, doing the work. Peace to you and yours!

We’ve got this. Stay tuned for my next post