In my book These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most, I'm basically after responsible reduction. How do we reduce the impossibly large list of potential things we could do with students into a pleasantly manageable list of things?

In other words, it's a book that attempts to introduce a gist of good teaching, in any content area. And so the other day when I was preparing for a speaking engagement on the book and looking over its pages, I realized that each chapter ends with a “gist,” and I thought these gists would be good to have all in one place somewhere on the internet.

So, here is that place. The gists from each chapter of a gisty book.

Chapter 1: Teaching Toward Everest

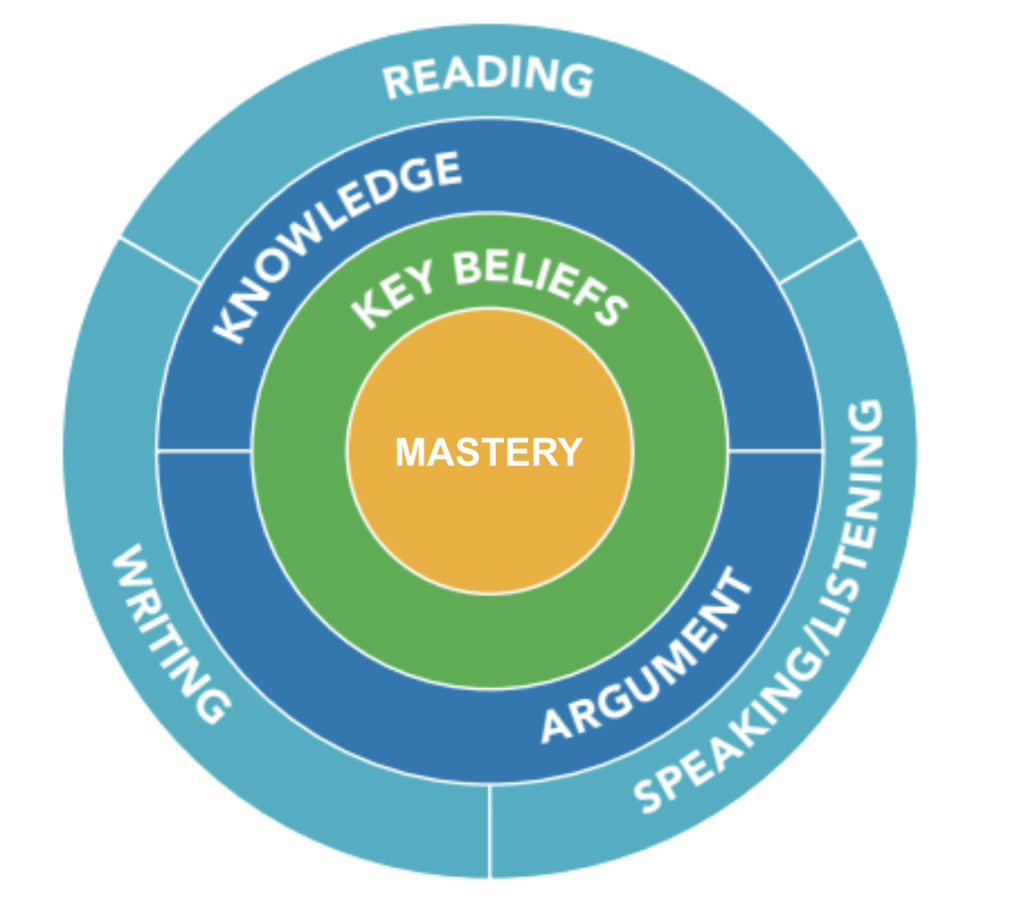

I made this book for teachers like me who are multivocational: we want to be excellent at our jobs for the sake of our students, but we're not willing to sacrifice our entire lives on the altar of teaching success. To start down this path, we need to be clear on our Everests. Our personal Everests matter, and they ought to be posted in our classrooms. Our collective Everest matters, too: the long-term flourishing of kids. This book will show us how six areas of practice are our best bet to be the teachers we always hoped we'd be and stay sane in the process. They are the six areas in which we ought to invest our instructional and professional development time: belief, knowledge, argument, reading, writing, and speaking/listening. These are six simple yet robust paths to explore in any given lesson, unit, or school year. Becoming experts in these six pursuits is, unlike the many things expected of teachers, both manageable and exciting.

Chapter 2: Cultivate Key Beliefs

Much has been studied and written about character, soft skills, noncognitive factors, social-emotional learning, and whatever else you'd like to call this constellation of life-critical attributes that don't appear on standardized tests. I've tried many of the approaches in the literature but have found none as coherent and manageable as the Five Key Beliefs suggested by two big works of research: John Hattie's teacher Credibility, and Camille Farrington et al.'s Value, Effort, Efficacy, and Belonging. I can target these through my actions as a teacher.

These beliefs aren't magical, and they certainly don't autocorrect for skill deficits or at-risk home lives. Yet they are critical levers for the rest of the work we'll tackle in this book. When our students believe these things as they experience our lessons targeting knowledge-building, argument, reading, writing, speaking, or listening, they engage with the work and they do it. That's not a silver bullet, but it's certainly a great start.

Chapter 3: Build Knowledge Purposefully and Often

There's no such thing as creating literate students who don't know a lot of things. Abilities that we prize in the twenty-first century, including the ability to learn, to read, and to think critically, are not transferrable to domains in which we have little knowledge. Because of this, it is difficult to conceive of a school that values literacy and mastery but does not give the ample time and attention required to identify key knowledge per course and develop best practices for helping students build this knowledge over time. The only way teachers will be able to climb this particular path on the mountain will be if they are given time and permission to focus their efforts and attention. Although this can all be overwhelming, we approach the mountain with a one-step-at-a-time, practical mentality. We won’t perfect our knowledge-building efforts this year, but it’s reasonable to expect that we can make them a little bit better—and add to our efforts and our students’ knowledge base each year.

Chapter 4: Argue Purposefully and Often

Argument is central to not just a life of the mind, but a life of constructive conversations and good decisions. To create classrooms in which the study and practice of argument is not confined to a unit, we need to cultivate what I call earnest and amicable cultures of argument, we need to give our students a large number of opportunities to study and practice argument, and we need to try our hand at improving the quality of student argumentative thought over time. We are so quick to push for quality in our secondary classrooms, but I’ve found I can only address quality once my students and I have been immersed in the work we’ve discussed so far. If argument isn’t situated in the context of a life-giving classroom culture, it’s not going to promote the Key Beliefs we’re after. And if argument isn’t a normal part of our classroom life—if we don’t provide kids with a certain quantity of argument—then it will always seem like a detached, one-off kind of exercise. As we increase the quantity of arguing our students are doing throughout the school day, we begin to create opportunities for improving the quality of those arguments.

We can work at all three of these areas simultaneously or focus on one at a time. How we approach these three recommendations depends on the time we have, the current state of our curricula, and the number of other things on our plates.

Chapter 5: Read Purposefully and Often

One needless cause of the literacy decline is a lack of reading volume in secondary schools. Each one of us can combat this without sacrificing content knowledge. We start by quantifying the reading we assign in each course and brainstorming “low-hanging fruit” methods for increasing that quantity. As we increase the quantity of texts read, we also need to increase the simplicity and effectiveness with which we support students and their reading—the nine moves in this chapter can suffice. And finally, when kids don’t do the reading, we must do more than throw in the towel; we can use the Key Beliefs to identify means by which to increase the likelihood that our kids do the reading and do it with care.

Chapter 6: Write Purposefully and Often

Whether we want to prepare our students to be “the rock stars of their generation” (Cepeda, 2012) or simply participants in the middle class, proficient writing matters. If our schools did a better job honoring content-appropriate, mastery-supporting writing throughout the school day, we’d be closer to meeting the Conley Challenge and improving our next dose of NAEP writing results. Unless we’re pragmatic in how we approach increased writing volume during the school day (the Pyramid of Writing Priorities in Figure 6.2 can help), we’re going to create short-lived, unsustainable initiatives around writing every single time. But once we are smart about improved writing quantity, we can begin systematically advancing writing quality: first, with grading-free approaches to making good writing sensible and concrete to our students, and second, with a satisficed approach to providing timely, next-day feedback. Finally, we have to examine how we’re approaching the dreaded task of grading. The simple, robust approaches we adopt need to be focused and aimed at speed.

Chapter 7: Speak and Listen Purposefully and Often

Speaking and listening are often neglected in our literacy teaching. These life-critical skills become the hapless victims of assumicide: because our students, for the most part, enter our classrooms speaking and listening, we assume that we don’t need to give them instructions, practice, and feedback in these areas. This costs us more than we’re aware of in terms of how well our students engage in and value our classes, and it costs our students more than they’re aware of, too. In the class that our shy or anxious students appreciate today because of its lack of public speaking, we find the culprit behind future, high-stakes failures in public speaking, whether on job interviews or first dates.

My solutions to this problem are, I hope, simple, predictable, and unoriginal. We first need to address quantity, and this can be done through the use of three kinds of speaking structures. And then we address quality through the simple no-paper-load means of responsive instruction, modeling, feedback, and reflection. In the speaking-rich classroom, all the other components of the Foundations for Flourishing bull’s-eye are easier to work on.

And, the whole book in an image looks something like this:

Leave a Reply