All right: finite creatures, only 24 hours in a day, only 4,000 weeks or so in a life. Got it. We've looked at DECIDE, CONSTRAIN, OBSESS — now today, a riff on the discipline of ELIMINATION.

(You may already be noticing that the disciplines overlap one another. Quite right. There's really not a ton to my way of approaching time management life stewardship as a husband, father, teacher, and writer. The DECIDE tool is a close cousin to the OBSESS tool; the CONSTRAIN tool another way of thinking about ELIMINATE.)

What can I say? Simple things for simple minds.

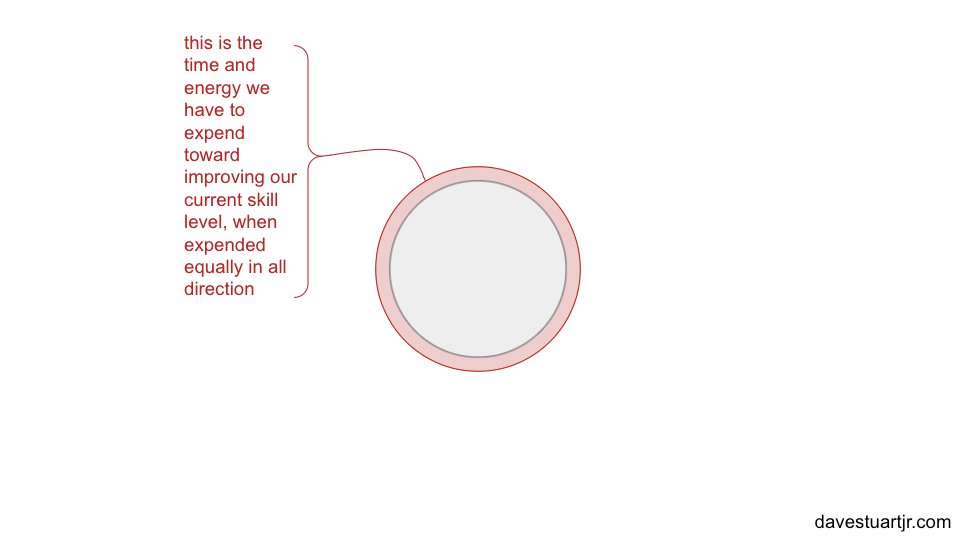

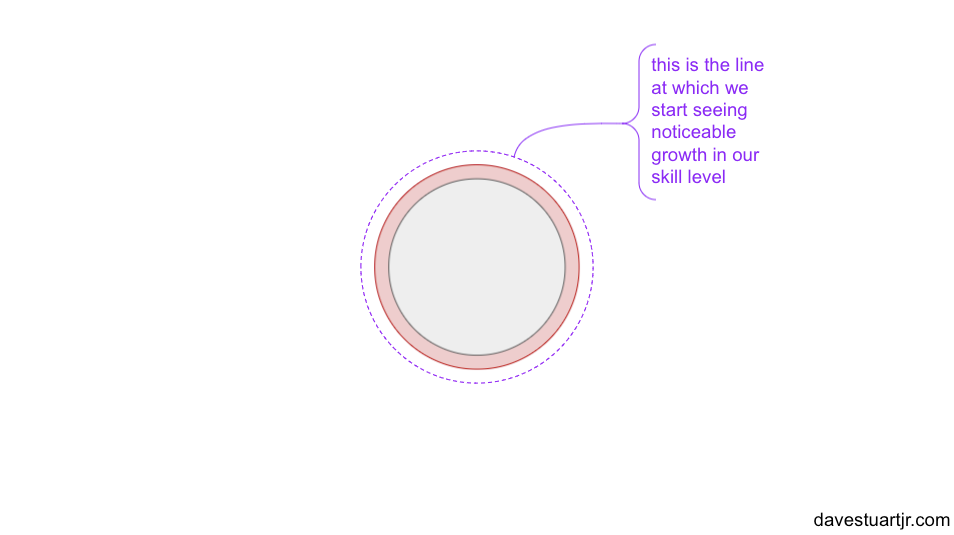

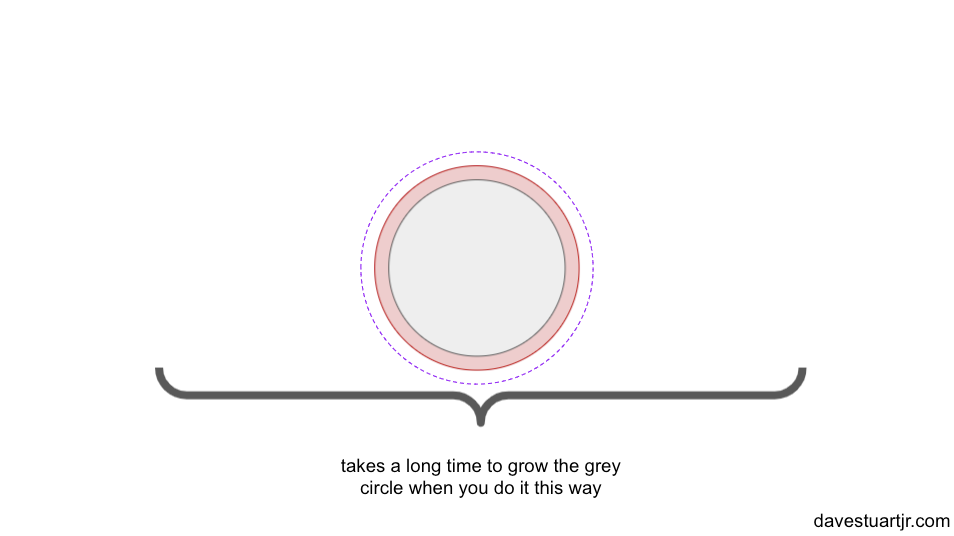

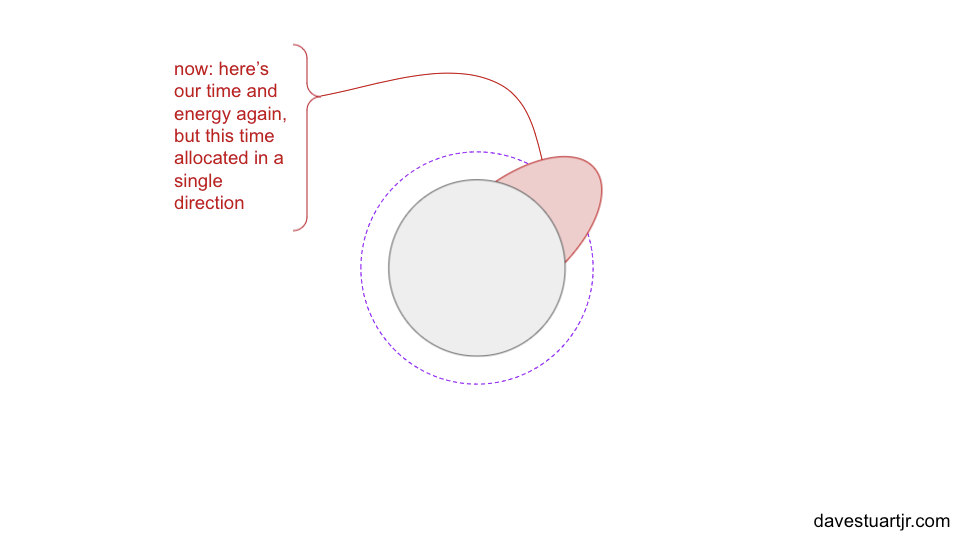

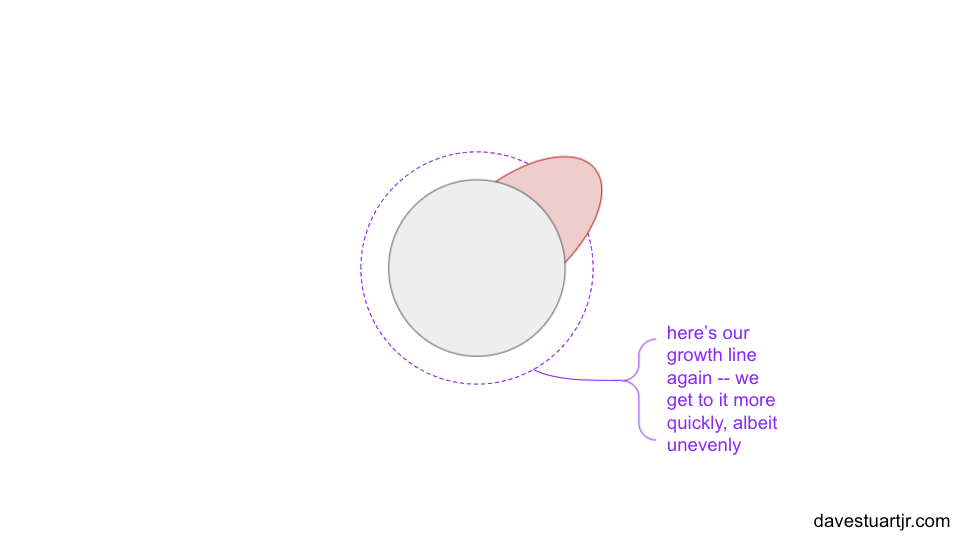

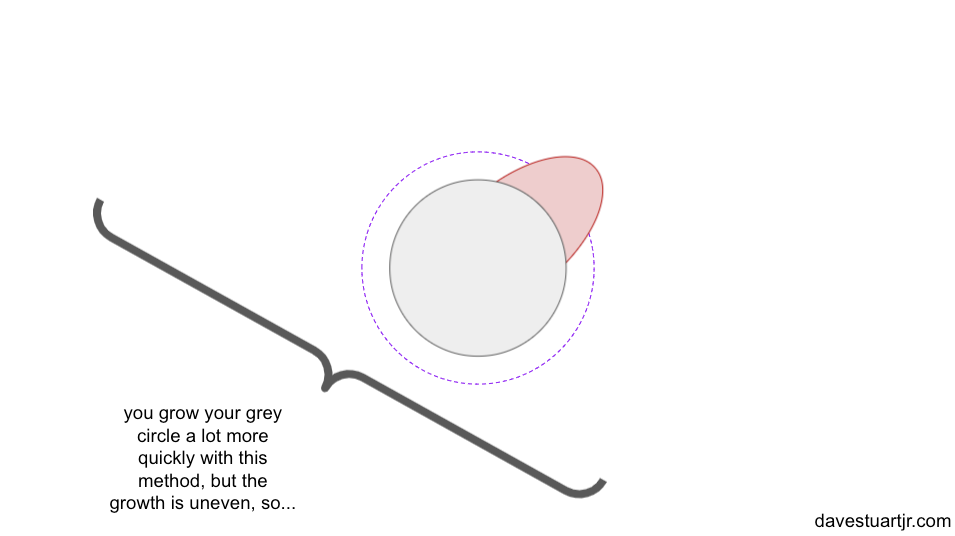

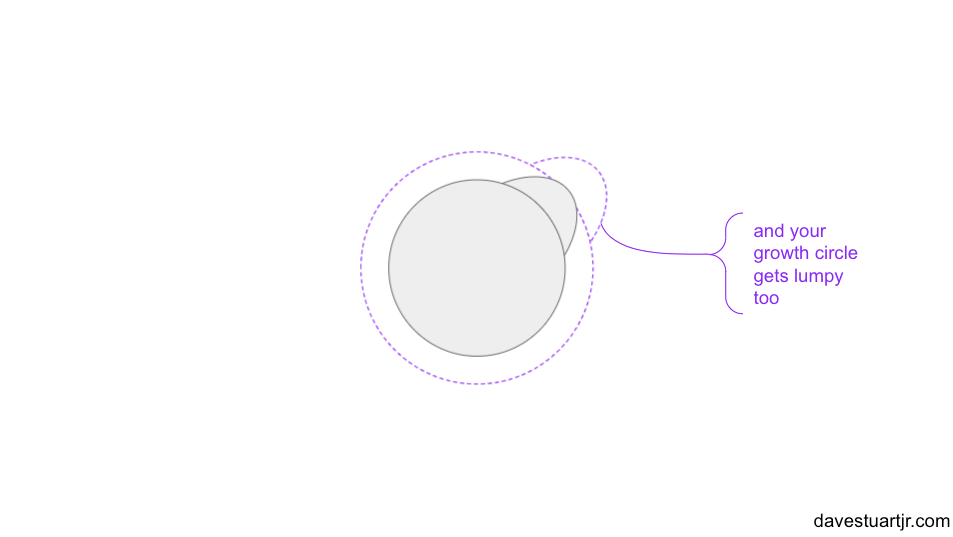

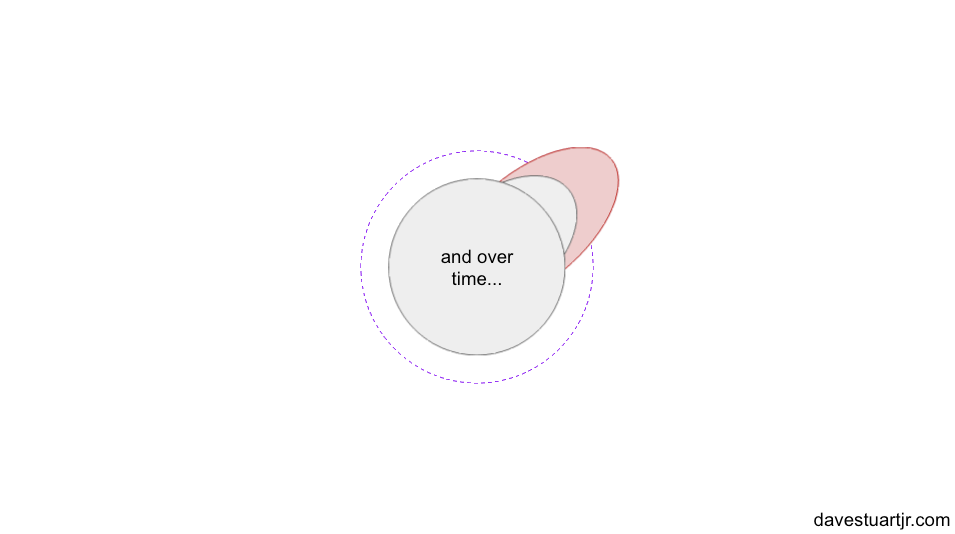

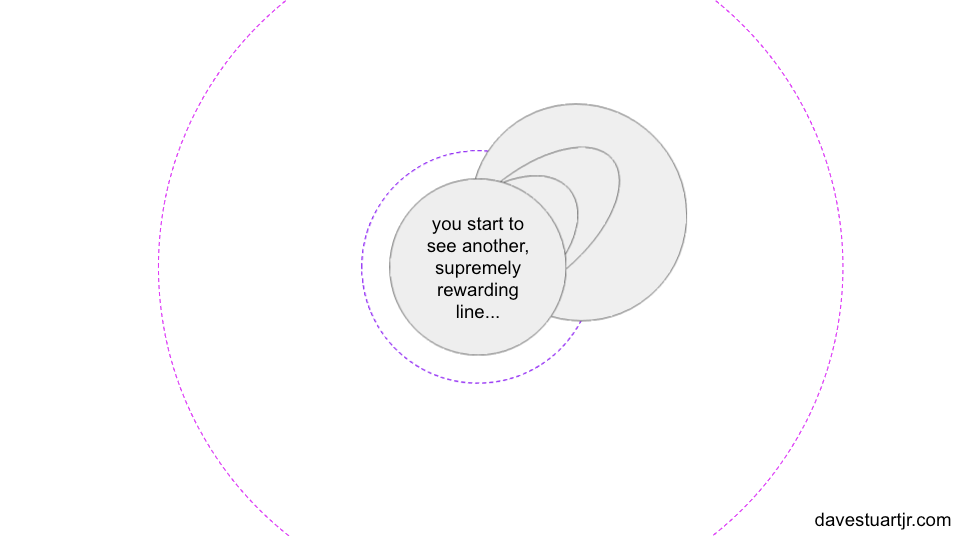

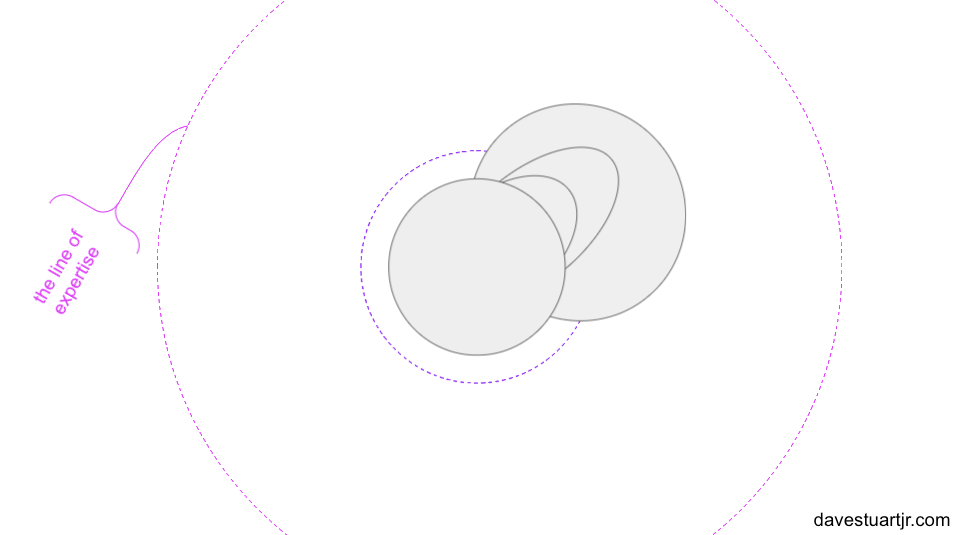

Let's get into today with the help of some sophisticated diagrams. (Make sure images are turned on if you're reading this in your inbox; for the visually impaired, I've made an effort at setting up some quality Alt-text for you.)

Now here are some things to know about my views on expertise.

First, expertise is viewed with extreme (and I think, often deeply foolish) skepticism in the United States. The culture is rife with the idea that experts are outdated; we can all be our own experts; you've got to be wary of what the experts tell you; “Who made you an expert!?” But I think at the root of this view is a misguided sense of reality as something that we individually determine for ourselves.

But reality is a poor partner with such ego-centrism.

For example: my students are autonomous beings. I cannot coerce their motivation. No matter how hard I squinch up my brow and wish them to want to learn, I cannot alter their motivation simply through my desire or determination — no more so than I can start my car by hopping in the driver's seat and staring hard at the steering wheel. Instead, I must use the ignition key in my car, and I must apprentice myself to the realities of the will in my classroom.

An expert is just someone who has spent a large deal of time stubbornly and intelligently and sustainably focused on fundamental questions.

- How are students motivated?

- How do students learn?

- How do I maximize the results of my classroom without sacrificing my life or my loved ones in the process?

Doggedly pursue these kinds of things enough, and you'll wake up one day to find, “Huh. I've got an evidence-based toolkit for answering these questions. I can clearly articulate where I'm strong and where I'm weak. I know where to go when I stop knowing what to do. When I see a classroom in action, I see with all these lenses I didn't always have.” And so on.

And so, expertise is marvelously valuable, personally and professionally. There is no greater prize in our own professional development than the slow and steady acquisition of expertise. But in a profession that loses most of its people before they reach five years' experience, expertise is rare. Calamitously so. Too often in our schools it is very much a blind leading the blind situation. The result is lots of human suffering. And mind you, there's no ill intent on anyone's part here — instead, it's just a dearth of real expertise.

And the lumpiness of expertise pursuit is part of the reason why. We're uncomfortable with accepting that most parts of our practice must be good enough in order for some parts of our practice to be exceptional. We don't want to be lumpy; we want to be uniform. We want all the parts of the teacher eval rubric to be shiny. We want Angela Watson and Jennifer Gonzalez and Matthew Kay and Penny Kittle and all the rest to nod approvingly at our practice. When a new edu-topic trends on Twitter, we think, “Well, that must be important — time to dig in.” When a lesson doesn't go well, we head to Google or TPT, not our teacher's journals — convinced that the answer is out there, all silvery and powerful, if only we could just click the right link.

But what's important is reality.

- What's really happening in our classrooms?

- In the hearts of our students?

- In their futures and pasts?

- What's our unique (and small, and precious) role: as teachers, leaders, parapros, psychologists, or speech paths?

The dogged pursuit of these kinds of questions will, in time, make us better partners with reality, folks more capable of parsing passing fads from important findings.

So I say, be lumpy. And start by ELIMINATING:

- Any commitment that you have — committee, club, team, role, seat — that's not aligned with your sled dogs. Is it time for a graceful exit?

- Any compulsive distractions you've made peace with during your work day. Is it time to delete or block? What could you do with that time if you invested it toward the answer to a single burning question?

Grateful to be teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Registration for the Time Management Stewarding Our Lives Seminar opens next week. Folks on the waitlist get first dibs. Interactive, cohort-based — it's going to be like a five-week mastermind group on getting the breakthroughs we long for in how we manage our lives. Details and waitlist are here.

Leave a Reply