Note: I expanded the arguments in the article below and provided practical teaching applications into a full chapter of my book These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on the Work that Matters Most. When you buy a copy, you directly support my work as a thinker and writer. -DSJR

Argument, my dear colleague, is precious.

I'm not being sarcastic here. Something that is precious (from the Latin pretium, or price) is highly valuable; it is to be treated with the greatest of care. Like an irreplaceable family heirloom passed down through the generations, argument comes to us not at the behest of some list of standards but rather at the behest of democratic civilizations. The ability to argue makes one able to read critically, to write logically and compellingly, to listen at a level beyond compliance, and to carry on complex conversations aimed at solving problems or settling disputes. Perhaps counterintuitively in a time when argument means citizens yelling at one another on social media, thoughtful, proper, listening argumentation is the bedrock not just of the best kinds of schools (as Graff and Birkenstein, 2017, say, “Argument is the lingua franca of academic discourse”) but also the best kinds of families, communities, and organizations. You see — argument is precious!

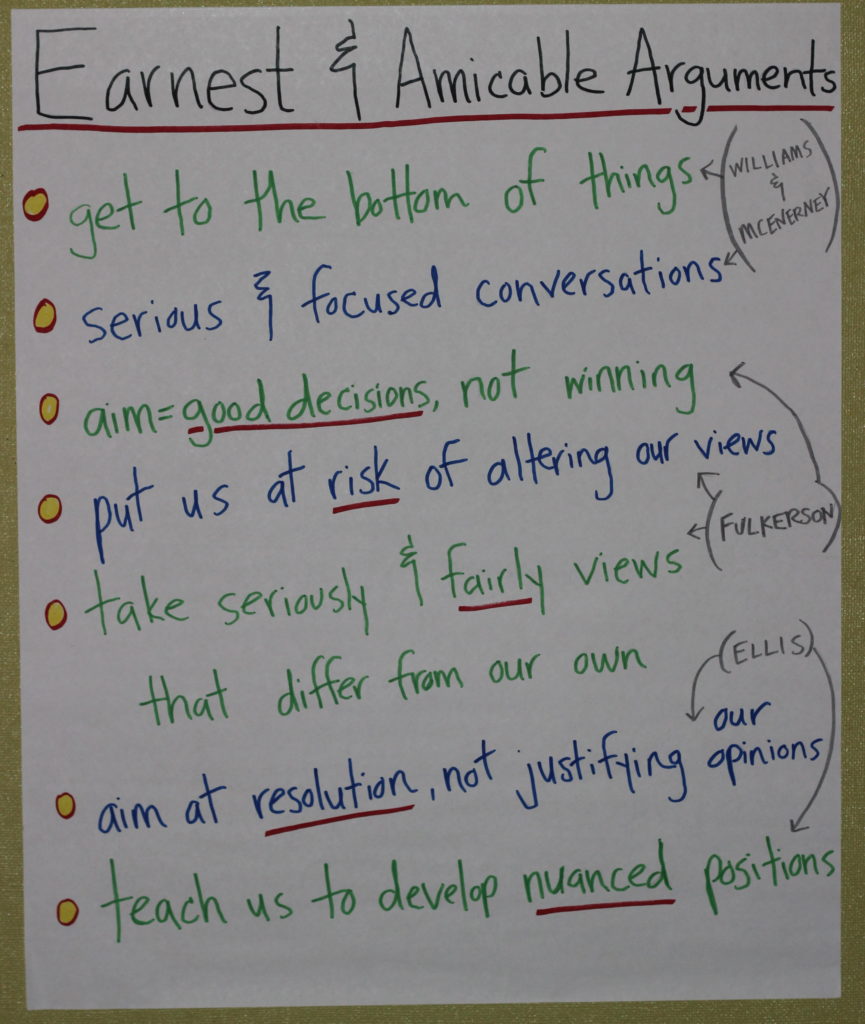

The only way this can make sense is if we conceive of argument as something broader and deeper than a zero-sum showdown. It’s “not wrangling, but a serious and focused conversation among people who are intensely interested in getting to the bottom of things cooperatively” (Williams & McEnerney, n.d.). Like Richard Fulkerson (1996), I “want students to see argument in a larger, less militant, and more comprehensive context — one in which the goal is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own” (p. 17). Lindsay Ellis (2015) calls for teaching the goal of argument as “com[ing] to the best possible solution to a problem through discussion” (p. 204), and helping our students see that argumentative practices teach us to “develop nuanced positions through a process of critical deliberation” (p. 209).

Earnest and Amicable Argument

I’ve called this “type” of argument all kinds of things over the years: “Fulkersonian,” after Richard Fulkerson; “collegial,” in the sense of the kind of arguments that great colleagues have together; and “collaborative.” The term I finally landed on, however, is “earnest and amicable.” (I know, I know, it’s not going to win me any “naming” awards, but naming has never really been my thing.) Earnest is important in its “sincere and intense conviction” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2018). It’s the opposite of flippant, apathetic, and half-hearted. And amicable is the other side of things, lest we become dreadfully serious. At its Latin heart (amicus), this word means “friend.” In Late Middle English, amicable started to mean pleasant or benign (Oxford Dictionaries, 2018). Earnest and amicable arguments are both serious and joyful, good for the mind and good for the soul. That’s what I’m after in my classroom. Below, you'll find a chart we created in my classroom to remind us of these points.

This is the argumentative culture — or, more accurately, counter-culture — that I’m trying to create in my classroom.

Why? Well first of all, this kind of argument promotes the long-term flourishing of kids.

What would the conversations around family dinner tables — or during long car rides, or in those hard moments with a close friend or sibling or spouse — look like if, when disagreement arose, all participants were fluent in this collaborative, resolution-oriented argumentation? How different would televised presidential debates be if getting to the bottom of things cooperatively was the norm? Or the social media chatter around those debates? Would the oft-cited “echo chambers” of 2016’s post-election analyses have existed in a world where we were all comfortable with being ever at risk of needing to alter our views?

I concede that not all of our students may need to develop the sharp, technical skills of the competitive debater, but I cannot conceive of a single child whom I don’t want to be excellent at having evidence-based conversations in which “the goal is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own” (Fulkerson, 1996, p. 17). I can be content if my children don’t grow up to be competitive debaters; I will feel that I’ve failed, however, if they lack lots of practice and competence with collaborative, cordial argument by the time they leave my house.

So there’s the long-term flourishing argument for argument.

Note: This is an excerpt from the bestselling These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most. Learn more about the book here.

References

Amicable. (1989). In Oxford English dictionary online (2nd ed.). Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/amicable

Earnest. (1989). In Oxford English dictionary online (2nd ed.). Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/thesaurus/earnest

Ellis, L. M. (2015). A critique of the ubiquity of the Toulmin model in argumentative writing instruction in the U.S.A. In Scrutinizing Argumentation in Practice. Benjamins (pp. 201-213) doi:10.1075/aic.9.11ell

Fulkerson, R. (1996). Teaching Argument in Writing. CA: National Council of Teachers.

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2014). (2017). They say, I say: The moves that matter in academic writing. Paper presented at the invitation of the Chippewa River Writing Project, Mount Pleasant, MI.

Williams, J. M., & McEnerney, L. (n.d.). Writing in college: A short guide to college writing. Retrieved from https://writing-program.uchicago.edu/undergrads/wic1highschool

celinargon says

I do agree with the idea that we need to approach arguments in this earnest and amicable way. (Even if the name is a bit of a mouthful.) I think that it is important to impart this on students and I might steal it for my future classroom.

I do notice that many people aren’t even approaching arguments, because they are unable to see the point in arguing if their ideas and opinions will fall on deaf ears. I was wondering how you would go about giving students confidence to speak up or how to create that environment in the classroom.