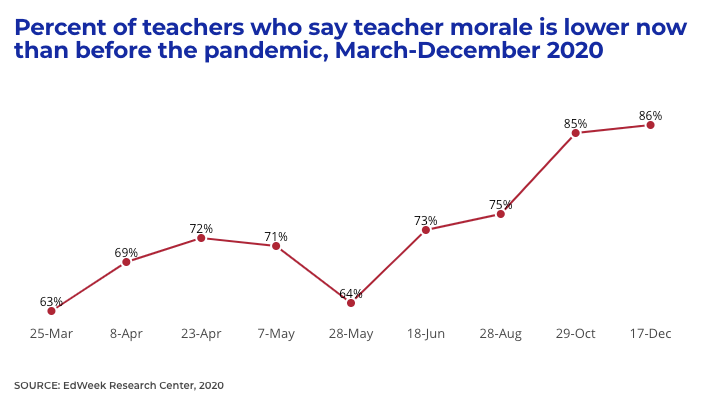

According to a recent EdWeek survey, teacher morale isn't great in the United States right now — at least not according to us teachers. Take a look:

When you look at that, you might be nodding your head. Me too. Not exactly a revelation, right?

A pause for perspective: it's not only us

Now listen. We teachers should be known for our love — for the degree to which we understand and care about the pains and concerns and triumphs and successes of all the folks in our society. After all, all the non-teachers we live with are or were our students or our students' parents. These are the people we serve.

So when we look at a chart like that, we have to remember that lots of folks are struggling right now; lots of folks felt that way heading into the end of 2020 and are feeling that way still. In such circumstances, the criticality of our care only increases.

And that is why the demoralization trend is such a big deal: demoralized people are pained people. Confused people. Job-searching people. Days-remaining-counting people. And I make those descriptions not by assuming what's been on your mind lately but by sharing what's been on mine.

This has been hard.

But it's also been hard on everybody.

So what can leaders do?

With those things said, in order to unlock the performance potential of teachers, you've got to seek remedy for this rising demoralization — not at the macro “fix the system” level, but at the micro “people in your actual life and on your actual team” level. Macro-level work is important but often overrated and almost always unresponsive to emergent needs. Right now, we've got to get our own houses in order — micro-level work. Because at this rate, we just need to keep good, smart, earnest people working in our classrooms.

So here's the good news: there's lots that leaders can do, and its not hyper-heavy lifting. Small, wise investments in teacher motivation can compound over time into high teacher morale. But before we get to those investments, let's talk about motivation.

There's nothing like motivation

Motivation is the state in which I want to do something in the deepest parts of me. Way deeper than carrots, way deeper that sticks. My desire is for the thing I am motivated to do; my will is pointed toward it.

There are five things that an optimally motivated teacher tends to believe:

- This work is valuable. It matters. It's going to make a difference equal to or greater than the effort and care I'm putting in.

- This work suits ME. People like me do work like this. I fit in the work of teaching.

- There are clear ways to get better at this. When I do those things with care and vigor, I'll improve at teaching. My effort pays off.

- I'm going to succeed. I know what I'm trying to do as a teacher, and I know that I'm likely to succeed in getting it done.

- My leader has what it takes. She is competent. He knows what he's doing. She cares about me. He's as into this work as I am.

These beliefs are at the core of teacher motivation — and, when generalized, are at the core of all true motivation. They are a knowledge that helps at a level deeper than cognition — things known not just in the head but in the heart. When a teacher knows those five things to be true, that is a teacher who will work hard and with joy, even amidst adversity. You don't have to incentivize her, you don't have to threaten her — she'll teach because in the deep logic of her heart, it only makes sense to do so.

Now, I use a shorthand for these “five key beliefs.” In the order of the list above: Value, Belonging, Effort, Efficacy, Credibility. I call these the five key beliefs, and they are an enormously helpful, evidence-informed model for analyzing and acting on questions of human motivation.

So what happens to belief when things go wrong, like so many things did in 2020?

When things go wrong for a teacher — and in 2020, a lot of things did — she'll naturally start to question her beliefs. It'll sound in her heart like…

- Value: Is this work valuable? Does what I'm doing as a remote teacher really matter? What if I'm doing more harm than good?

- Belonging: I'm not a very technological person — this kind of teaching really isn't me. I kind of liked teaching from home, and now I'm not sure if I fit back in a standard school setting. Maybe I'm not cut out for this.

- Effort: I'm overwhelmed at all the new things there are to learn. I can never make progress. What if I'm just wasting my time with the extra effort? What if it doesn't pay off?

- Efficacy: I'm not sure I'm going to succeed this year. I don't know what I'm doing.

- Credibility: My boss is overwhelmed. She seems like she's about had it. I haven't spoken with him one-on-one in months.

The human being is a wonderfully and fearfully moldable creature. It is this quality of humans that makes schools so packed with potential, and it is this quality that makes the work of leadership more like gardening than computer programming.

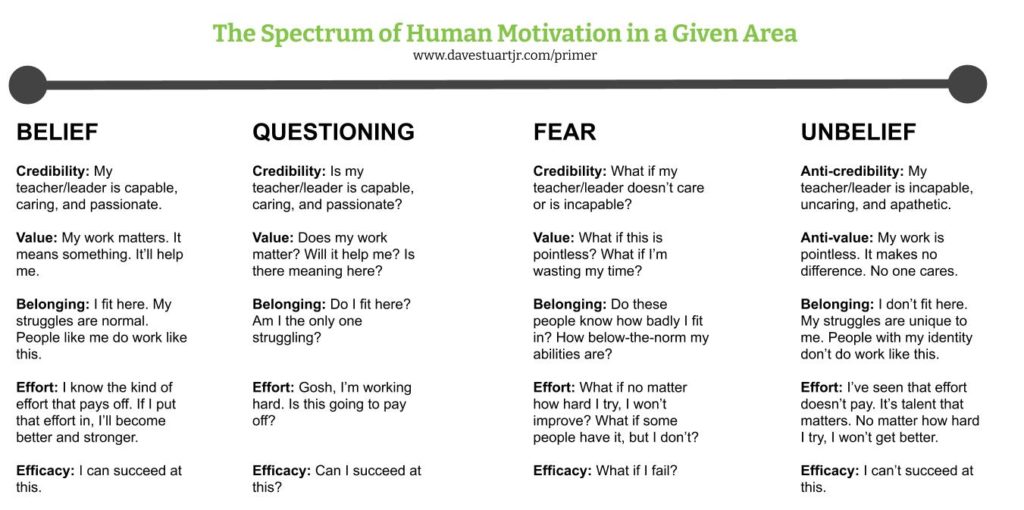

When bad things happen to a motivated teacher, the teacher will start to question the five key beliefs. Remember, much of this happens beneath cognition at the level of the will (or heart). If things keep going badly, the questions can become fears. Apart from intervention — from a leader, a friend, a student, a providence — new “anti-beliefs” can form that prove ripe for demoralization.

Here's a visual depiction of what I'm talking about:

But there is good news about when things go wrong

I first learned about the five key beliefs while doing research for my book, These 6 Things. I was interested in the factors within our control that differentiate between students who are eager to do the work of learning with care and students who are resistant to it. In short, I wanted to understand motivation. The five key beliefs are the fruit of that inquiry. They're found not in any one study, but rather serve as a shorthand way of remembering the findings of a whole host of studies. (Such shorthand models are critically important for active practitioners because such things are about all we have with us during the hurly-burly of a given school day.)

My point in mentioning this research is that there's a pattern in some of the studies: beliefs (or, to use the language of psychology, “mindsets”) are especially malleable during times of transition, and the status of a belief and the end of a transition time is fairly predictive of its state a long ways down the road.

In other words, beliefs work kind of like bones. If you break a bone, its healing can go two ways:

- If it's not set properly, it'll grow back as a rather permanent deformity.

- But if it is set properly, it'll grow back good as new and in some ways stronger than it was before.

In short, every educational leader seeing low teacher morale right now is actually seeing a time of great opportunity to bring some basic, loving practices to bear on people who need it.

So that's plenty of principles for one day. Let's not get ourselves overwhelmed, and instead let's start playing with evidence-supported strategies and interventions that you can use with your team.

Ten Things Leaders Can Do to Improve Teacher Morale in January 2021 and Beyond

To organize our walk through evidence-informed practices for improving teaching morale, we'll use the five key beliefs. Let's start with Credibility.

Credibility boosters: Interventions that will help teachers believe that you care, you know what you're doing, and you're passionate about this work.

Too many leaders trick themselves into thinking that their teachers don't care much about them. But look, people think a lot about their leaders. It's just something about us — we all do. That means that understanding how credibility works and how to influence yours is a matter of practical importance — it need not be pride.

Credibility is a matter of CCPR: Care, Competence, Passion, and Repair. (More on CCPR here.) Teacher credibility is featured prominently in John Hattie's visible learning list, but less has been said about the motivational impact of leader credibility. Here's how to improve that.

1. Track attempted moments of genuine connection with each of your staff members. If you've got a smaller team, try to do one MGC per week for each member; for larger teams, shoot for biweekly or once a month. The gist of an MGC is that you're seeking to communicate to a person that you value, know, and respect them. (And of course, there's a prereq for that.) Doing this for all members of the team on a consistent basis, in the words of one of my colleagues, is so powerful that it's dumb. I've made a brief explainer video on MGCs here, and I did an interview with Jenn Gonzalez on the topic here.

2. Demonstrate your competence by solving a problem everyone is having and following up when it's through. There are few quick paths to competence — you get there through the consistent application of intelligent effort. Some of that effort is placed into learning by reading posts like this one. (Good on ya!) Some of it has to be placed on following up with people about the problem(s) they've shared with you. It doesn't take a huge amount of time to follow up, but the impact on a teacher's perception of your competence is significant.

3. Demonstrate passion for your work by identifying 2-3 shorthand phrases for the mission of your school or the enjoyment you get from working with your team, and infuse these phrases as genuinely and generously as you can into as many conversations as possible. That's a wordy one, but the gist is that smart catchphrases build culture, reinforce norms, and when they come from an earnest leader, enhance credibility. An example of this would be elementary principal Andy Secor's use of the phrase #ChaseIt with his teacher teams. Other phrases might be “Eyes on Everest” or something that quickly summarizes your school's mission or story.

(This idea of story-based communication is something I'm thinking more about lately thanks to Don Miller's work in business communications, but I'm not far enough to write on it yet.)

4. In situations where you and a team member have a frayed or fraying relationship, seek repair. At least one study has demonstrated that the state of being offended by a teacher — embarrassed, humiliated, offended — coincides with drastic reductions in credibility. It's a commonsensical idea: if you offend someone, it's likely to hurt their perception of your care for them. The trick, of course, is that it's possible for you to offend someone without meaning to — but within that trick lies a great beauty of human relationships. I've written a bit on identifying situations where repair is needed and how to seek that repair here. (Even though that article is written to teachers, the same principles are at play in leader-teacher relationships.)

Value boosters: Interventions that will help teachers believe that the work they do matters.

5. At the start of your next staff meeting, ask teachers to write freely about 2-3 things about teaching that they value. Encourage them to explain in their writing why these things are important to them. Invite teachers to share in small groups or as a whole team. I would introduce this to the team with something simple, along the lines of, “I thought this midpoint in the school year might be a good chance for us to take a few minutes to reflect on the fundamentals of this work and how our hearts engage with it. I'd like us all to spend the next five minutes writing about 2-3 things about teaching that we value and why we value these things. In your writing, forget about editing or sounding a certain way — no one is going to see your work. This time is for you. Go ahead. Afterwards I'll ask for some volunteers to share, and then we'll move on with today's meeting.”

What you're doing here is creating space for a work-specific values affirmation intervention. Studies have demonstrated this intervention's effectiveness for improving Belonging, and since we've linked it with the value of our work here, it'll help with Value, too.

(Here's more on how teachers can do this intervention in a class setting.)

6. At the start of a different staff meeting, ask teachers to brainstorm connections between their outside-of-work lives (hobbies, interests, life goals) and things that they have been learning or practicing in their work. This is just the “Build Connections” intervention that UVA researcher Chris Hulleman has developed and popularized with the help of Character Lab. This one takes a little extra planning — I always recommend teachers do it on their own before trying to do it with students — but it would certainly be a fruitful exercise for increasing the degree to which teachers are able to see the value in their work — specifically the work's utility value (its usefulness).

(I've written more on using Build Connections with students here and here.)

7. Shark Tank… content area edition. Before your next staff meeting, ask 3-5 of your more outgoing staff members to join you in a fun activity where you'll each “pitch” the staff on why a given content area is worthy of study. So for example, if you've got a spunky math teacher, have him prepare a 60-second pitch for why math is worthy of study, or if you've got an especially passionate science teacher, ask her to prepare 60 seconds on why science is beautiful, or maybe let that earnest Computer Science teacher have a go. Importantly, encourage the pitching teachers to AVOID denigrating other subjects in their pitch. The award for a good pitch is applause and smiles and laughter.

A big part of the benefit of a meeting opener like this is that it's fun — and certainly, fun helps with morale because it's easier to value things that are enjoyable than things that aren't. There's also a Belonging boost that surely comes with laughing and smiling together. But one additional cool side benefit of this activity is that it gives staff a chance to reflect on a core value that every school in the world should have: learning in all of the disciplines is a beautiful and worthy act. We do not seek to compete with other disciplines and instead want our students to see the value of apprenticing themselves to all of them.

Belonging boosters: Interventions that will help teachers believe that people like them do work like this.

8. Give “magical” feedback. The other day while reading Kim Marshall's memo, I was blown away for a minute by this quote from a recent summary of Gallup survey insights from 2020.

Although leaders may fear being micromanagers, most employees receive far too little feedback — and even those who receive negative feedback would prefer to get more.

From “7 Gallup Workplace Insights: What We Learned in 2020” (Thank you to Kim Marshall for pointing me to this one)

One of the hardest workload puzzles involved with leading large groups of people — and whether you're a leader of teachers or a teacher, you lead large groups of people — is that fast, effective feedback is critical for motivating people long-term. And why is that? Feedback does all kinds of things for the five key beliefs:

- It communicates that the feedback giver cares* (Credibility)

- It communicates that the work upon which the feedback is being given is valuable* (Value)

- It points the feedback recipient towards how to use their effort in the future* (Effort), which contributes to greater success down the line (Efficacy)

But here's the thing:

*Only effective feedback does this.

We don't have time to go into great depth here on what makes effective feedback (Matt Johnson's book is excellent, with lots of leadership connections), but let me give you a quick intervention from the Belonging research that's pretty cool. A team of researchers led by Stanford's Geoff Cohen analyzed the impact of various kinds of written feedback on student work, and they found that one type of feedback outpaced all the rest in improving subsequent effort. Here's the line: “I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations, and I know that you can reach them.”

This “magic feedback” framing communicates belonging to a person, making clear that which is often ambiguous. When we get challenging feedback, we often fear, “Wait… am I bad at teaching? Does my boss think I'm a bad teacher? Is he out to get me?”

That's why the magic feedback framing works so well in encouraging subsequent effort — it diminishes the need for asking these kinds of doom loop questions.

(Here's the Cohen et al study.)

9. Show 2-3 #EducatorEncouragement videos and give your staff time to share their own experiences and tips with one another. In the Belonging research, there's this interesting interventional method that researchers use called “attributional retraining.” The idea is that when people are questioning whether or not they belong — when Belonging is ambiguous, such as during a time of hardship or transition or isolation — they tend to interpret negative events as a confirmation of their lack of belonging.

In other words, when we're afraid we don't belong, we start attributing negative circumstances to our lack of belonging.

This is, of course, demotivating. Which makes it harder to work at our problems. Which makes it more likely that we'll experience more negative signals.

Enter the doom loop.

To arrest this negatively recursive process, researchers expose participants to attributional retraining. It works like this:

- Participant views or reads remarks from respected peer(s). The remarks hit on three themes:

- The respected peer(s) experienced negative events during X time or transition period.

- The respected peer(s) realized that it wasn't just them experiencing these things and that it was, in fact, a normal part of X time or transition period.

- The respected peer(s) learned new strategies for improving their circumstances and getting through X time or transition period.

- Participant then writes or records an explanation for why the respected peer commentary they just read/viewed makes sense and how it connects with their own experience.

(Note: The “respected peer” samples were anonymized, e.g., a college freshman might read an excerpt attributed to “African American male, college senior.”)

Some months ago, I created an attributional retraining intervention of sorts here on the blog. I called it the Educator Encouragement Project. (Laws of Motivation 101: Never explicitly refer to what you're doing with folks as an attributional retraining, even if that's exactly what it is.)

You can find a whole playlist of videos that teachers around the world created here. At your next staff meeting, try playing 2-3, and then ask your teachers to share with one another how the videos connect with their experiences this year.

Effort and Efficacy boosters: Interventions that will help teachers believe that effort can make things better and eventually they'll succeed.

10. Make wise effort as clear as you possibly can. One of the greatest misunderstandings around growth mindset is that if we can just convince people that their intelligence is incremental rather than innate, then they'll put forth more effort, and they'll succeed.

The trouble here is simple: not all effort works.

The last thing we want teachers to do is try harder at things that are inefficient or self-defeating. For example, the teacher grading every single student assignment because he believes this is the only way that students will be motivated to do the work of learning… this teacher needs a new method for thinking about motivation, NOT a new belief in the likelihood of his effort paying off.

Any time that a leader can bless a teacher with clear, simplified guidance on how to do something effectively, that leader has made a beautiful investment in the teacher's ability to succeed, and that, in turn, will contribute to the teacher's downstream belief in Effort and Efficacy.

Of course, trite oversimplifications of the work of teaching don't work for this. Only working ones do.

There's more I can say about these beliefs and how leaders can influence them, but there's a limit to how much time I have to write it all down as a teacher. What I hope is that this list helped and didn't hurt. If you appreciated it, please consider subscribing to the newsletter and sharing the article with folks you think it'll help.

Teaching and leading right beside you,

Dave

Leave a Reply