Apparently this is Paul Graham week, colleague. Last time, we looked at a pop-up debate about the value of writing, using a Graham essay as catalyst for the arguments.

Today, I want to give you a chance to reflect on what Graham argues makes a good teacher. This isn't a question he gets asked often — it's on his Rarely Asked Questions page, and he's more of a hacker/painter/investor/thinker than he is a teacher — but I think his answers connect well with the five key beliefs way of thinking and doing things about student motivation.

“The best teachers I remember from school,” Graham begins, “had three things in common.” As we briefly examine each, make special note of Graham's explanations. Those are where he offers special insight.

“They had high standards.”

We've all heard this, right? But look at Graham's explanation: “Like three year olds testing their parents, students will test teachers to see if they can get away with low-quality work or bad behavior. They won't respect the teachers who don't call them on it.”

Boom. Ouch.

What do high expectations do in the heart of a learner — whether the learner is three or thirteen or thirty? What does it do for my ninth grade students when I teach them toward standards as lofty as mastering world history or writing profound essays?

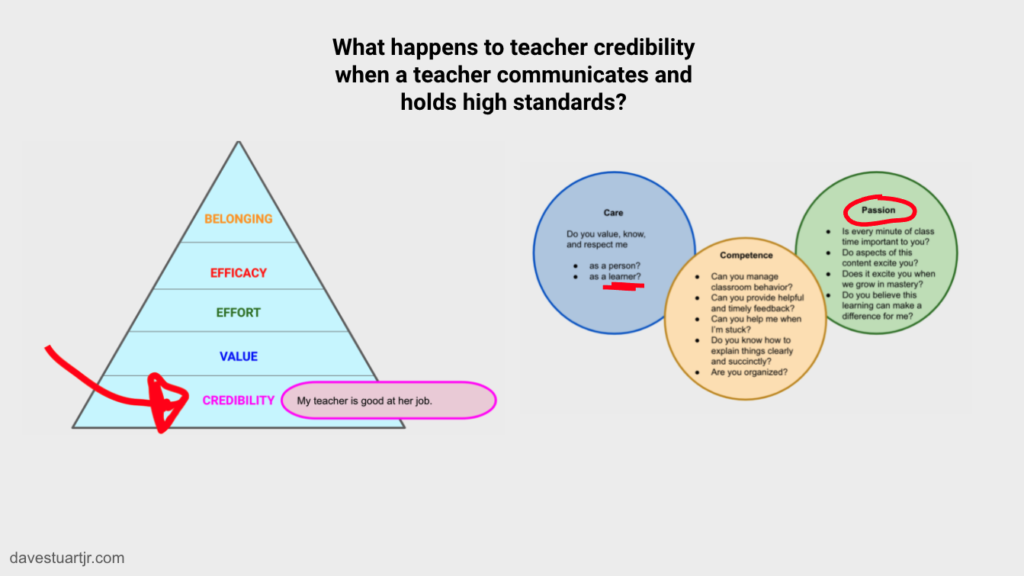

First, high standards communicate that I care and am passionate about this work. In other words, they signal that I'm credible — that I'm good at my job.

- CARE: I value and respect you enough as a learner to teach you, specifically, toward these high standards.

- PASSION: It matters to me that I teach you toward high aims. I feel in my bones the delightful responsibility of getting to be your teacher toward these challenging objectives. It is urgent to me. This is the only ninth grade year of your life — I want to help you make the most of it.

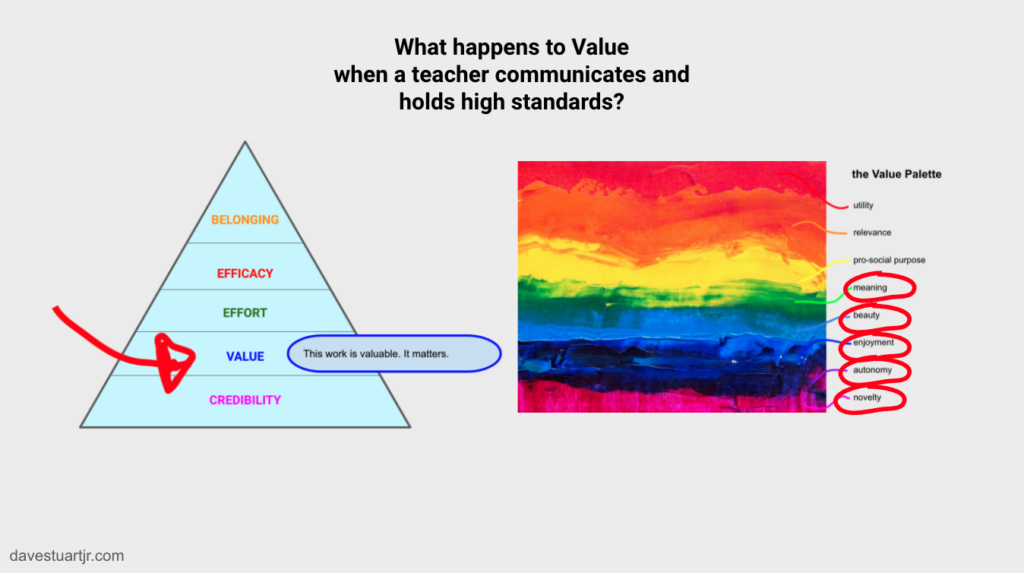

Second, high standards signal Value. When we consistently teach toward and hold students to simple high standards — e.g., listen while others speak; everyone participates in pop-up debates, even those of us who are shy or anxious; skull and crossbones errors aren't something we accept of ourselves in here; we all memorize a handful of dates each unit because we all can; we write (a lot) — we imply that this stuff MATTERS. That there's a deep structure of MEANING and PURPOSE in this work.

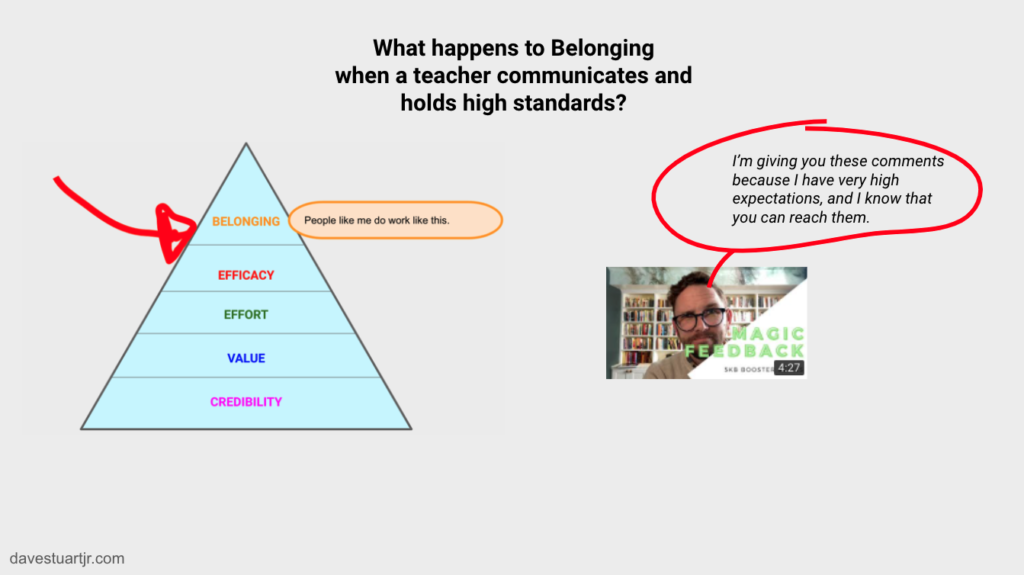

Third, high standards expand Belonging. When we expect each of our students to grow toward high standards, we send a message akin to Greg Cohen's magic feedback bit. Remember that? The researchers prepended student essay feedback with “I'm giving you this feedback because I have high expectations and I know you can reach them.” Study participants who received that message with their feedback were significantly more likely to apply feedback to future drafts and submit better quality essays — especially African American students who were under-represented at the school being studied.

“They liked us.”

Again, Graham's explanation gets us thinking: “Like dogs, kids can tell very accurately whether or not someone wishes them well. I think a lot of our teachers either never liked kids much, or got burned out and started not to like them. It's hard to be a good teacher once that happens. I can't think of one teacher in all the schools I went to who managed to be good despite disliking students.”

What's liking a student help us do?

- It signals Care, which helps our Credibility.

- It stokes our own motivation — it's easier to serve people you like.

- It cultivates Belonging — we like being in places where we sense that people like us.

What's the thing most folks underestimate about liking students?

- That it takes work! Sometimes we teachers, smart though we are, get side-swiped to discover that we don't naturally like all of our students. This was nothing like I pictured when dreaming up this job! we moan. But — it's just one of those things. Most humans don't have an easy time liking all other humans. Which means most humans… well, we've gotta work at it. We've got to pray, reflect, meditate, soul search, force a smile, focus on the good.

It's hard, ya'll. And figuring out how to like all kinds of people is literally one of the most personally profound things that this job can give you.

“They were interested in the subject.”

“Enthusiasm is contagious,” Graham explains. “[A]nd so is boredom.”

Ouch.

I'm reminded of one of the first blog posts I ever wrote for this website, which revealed the heretical-in-some-circles-*cough*-English-teacher-circles truth that I'm not a natural fan of Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. Here's the post. I'm not ashamed. (Okay, I'm not totally ashamed.)

But a big inflection point in my teaching career was when I realized that I needed to find a way in to liking that book. And as it turned out, the way in was telling my students one year, “Hey ya'll — we're about to read the first page of this novel, and before that page is through you're going to be confronted by the reason that — make sure you're sitting down — Bradbury sometimes drives me crazy in this book.”

“While I read the first page or two aloud, I want you to try to understand what he's saying. And then, I want you to try to guess what drives me a little nutty sometimes with this book.”

We do it, and a student eventually guesses something to the tune of, “Um, because he's got about 107 uses of figurative language in the first paragraph?” And what's begun is a unit-long conversation about whether students do or don't agree with me.

And now? I love it when I get to teach the unit with that novel in it because I love the conversations about the language and the conversations about the themes and the way Bradbury compares Beatty to a snail with salt on it (okay no, not that last part, still grosses me out).

My point is — the way to enthusiasm, sometimes, is right straight through the thing that makes you unenthusiastic. But you've got to do it with a heart that says, “I'm so all-in on teaching you all today that I'm being a good sport about this unit and bringing passion to something I don't naturally enjoy at the 100% level you might think teachers enjoy things.”

And that? It helps.

So, let Graham's three things marinate in you for a bit. Think on them. Use them as a measuring stick up against where you're at right now in your practice.

And ask yourself: what would it look like for me to try getting one percent better at one of Graham's three?

It'll be fun.

Best to you, colleague,

DSJR

Leave a Reply