Note from Dave: Below, my colleague and friend Doug Stark introduces his newly re-mastered, four-leveled Mechanics Instruction that Sticks series of warm-ups for English teachers. For my secondary English teacher readers, you'll probably be interested in this whole post; for my non-ELA teacher readers, let me suggest the section of the post titled “Principles Underlying the Warm-Ups.” In this section, I think Doug lets us into the thought processes that lead to him being a perennial favorite teacher in our high school, not to mention a very high-achieving one.

Whenever I hear about a teacher like that — one who both connects with kids and helps them achieve abnormal levels of success — I'm curious. I want into that teacher's head.

Without further ado, here's Doug.

A Preface to the Third Edition of Mechanics Instruction that Sticks

About a four years ago, Dave Stuart talked me into putting together a workbook featuring some practical warm-up exercises for English teachers to use as a supplement to writing instruction. Dave had been trying to convince me to take on this project for some time, but I was hesitant to give up my downtime, especially considering that I had recently been sent to AP training and was preparing to take on four sections of AP Language and Composition.

Anyway, using his well-developed powers of persuasion, Dave broke me down, and I gave in. I spent several weeks of my summer trying to put together an organized, practical book of warm-up exercises that teachers could use and adapt as they saw fit. The result was the first edition of Mechanics Instruction That Sticks (fantastic title—Dave’s idea).

I have also noticed a need to provide older students (10th – 12th) with some activities that will help them recognize and correct errors that they make in their own writing. Accordingly, I've been trying to adapt some of the activities that I included in the first edition to match the needs of older students.

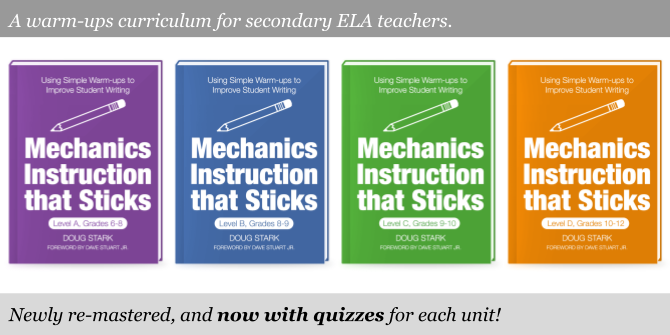

I’ve also received useful feedback from teachers across the country who purchased the original version. I’ve taken this feedback, and that brings us now to the third edition of Mechanics Instruction That Sticks — now with four levels and quizzes.

(To read the full introduction to Mechanics Instruction that Sticks, for free, click here.)

Principles Underlying the Warm-Ups

I should point out the key principles that I believe make these warm-ups as effective as they can be in supporting student achievement.

1. Repetition leads to mastery.

Most kids don’t master a concept because the teacher “touched on it.” Instead, they learn the concept by repeatedly engaging with it at various points throughout the school year. This is why I space out and review the sentence structures throughout the entire year. It is also why I incorporate a review element in the warm-ups.

2. Knowledge comes before mastery.

Many of our students need to develop a base of knowledge or a vocabulary that helps them identify problems within their writing and the writing of others. I want my students to be able to explain to me WHY one sentence is better than another. They can’t do that unless they can understand some basic concepts and define certain errors or problems.

This doesn’t mean that they need to know anything and everything about grammar. I’m a high school teacher, and, quite frankly, I do not have time to go back and re-teach every grammatical concept that students should have mastered during their time in elementary school. For this reason, the notes I use with my warm-ups tend to be fairly simple and concise. For instance, I don’t break down phrases into various categories because I don’t believe that doing so is an efficient use of my time. If I can get my students to understand the difference between an independent clause, a dependent clause, and a phrase, I’m doing pretty well. I approach each mini-unit thinking, “What information do the kids really need to know in order to master this concept?” Then I try to hammer that information into their heads (gently and lovingly, of course).

3. Kids learn best when they receive feedback and are able to talk through their learning.

I “teach” these warm-ups. When I say that, I mean that I actively lead the students through them. I read through instructions and complete certain problems with them if I think they need the help. While they’re working on the warm-ups independently, I walk around the classroom, targeting students who I know need added support.

Most importantly, we correct every warm-up in class. I call on students randomly as we go over the correct answers. Students learn to quickly and concisely explain their edits or revisions.

I also call on at least three students to read the sentences they’ve created (following the models provided). When they read their sentences aloud, I have them read the punctuation aloud so the entire class can hear where they’ve placed it. If a student makes a mistake, I gently explain why the sentence was wrong.

This may sound like it takes a long time, but it doesn’t. As I will lay out further in the Introduction, the entire process should take between 8 and 15 minutes, with the longer end of that happening if you have to stop and really explain a concept that kids aren’t getting.

My Procedures

At this point in my practice, my basic procedures are as follows:

- My students get a three-ring binder at the start of the year. In this binder is the student notebook included in the product package. This includes all of the unit notes (not the warm-ups, just the introductory notes) from Mechanics Instruction That Sticks.

- We begin each mechanics/grammar unit by turning to the introductory notes in our binder. We take 10-15 minutes to read through and fill in these notes together. That is our “warm-up” for the day.

- After we’ve gone through the introductory notes, we move on to the warm-ups. I will begin class with a warm-up 3-4 days a week. If we don’t have time for a warm-up on a particular day, we don’t do one.

- We apply what we’re currently learning (or have learned) to any and all writing assignments that we’re doing in class. Sometimes I’ll require students to include a particular sentence structure in their writing. When we are editing or revising, we place special emphasis on whatever focus area we’re currently studying.

- Most importantly, my students write a LOT.[1] I don’t grade all of it for mechanics and grammar because I’m not Superman (I guess those people in the documentary will have to keep waiting…), but I do make sure that we engage in some type of intentional editing or revising activity with every writing assignment—even if I’m only going to give kids a quick homework grade for completing it.

Final Thoughts

I think good teachers are able to set their egos aside in order to better serve their students. Good teachers are able to detach themselves emotionally and examine their teaching practices rationally so that they can make adjustments and improve their instructional methods on a year-by-year basis.

Because I firmly believe in setting aside the ego, I won’t be offended in the least if you play around with these warm-ups and use them as you see fit. If you want to teach the units in a different order, go for it. If you want to add or subtract from particular activities, feel free. If you want to print these out and hand them out to students as they walk through the door, go ahead. If you want to put a copy on the data projector and have kids work on them in their notebooks, no problem.

My hope is that you can find a way to use these activities productively within your classroom and that they make your life a little easier. Like Dave always says: more learning, less stress. Best of luck.

Sincerely,

Doug Stark

Footnote:

[1] When I taught ninth graders, we wrote six major essays (typed, 3-5 pages), along with at least 1-2 shorter compositions per week (1 or 2 paragraphs in length). My AP Language and Composition students write 18-20 full-length essays/papers, along with at least 20-30 shorter compositions (1 or 2 paragraphs). (Note from Dave: Doug is an animal.)

Gerard Dawson says

Doug and Dave,

I was enjoying this article as I read through the principles, and then came to this:

“I think good teachers are able to set their egos aside in order to better serve their students. Good teachers are able to detach themselves emotionally and examine their teaching practices rationally so that they can make adjustments and improve their instructional methods on a year-by-year basis.”

This is the kernel of wisdom in this article that transcends grammar instruction, English Language Arts and teaching in general. This is such a good point, and a hard thing for me to do in the classroom consistently.

Thanks for a great mixture of practical tips and a reminder of what’s important.

davestuartjr says

Gerard, thank you! You and I are a lot alike — reading the remarks of a master teacher like Doug is bound to turn up some kernels. Keep up the hard work, Gerard.

Kay says

I have read the article and the download; however, I am still a little confused. I haven’t found the level B worksheets or instructions. Are they labeled as A and B.

davestuartjr says

Hi Kay,

Many worksheets have an A and B side; however, Levels A, B, and C refer to three separate levels of the MITS warm-ups.

Annie says

Hi, Dave! I am loving the MITS resource and am planning on implementing it this year with my 9th and 10th graders. I was wondering if you have a sample calendar of when/how you cover each unit. How long do you spend on each of the concepts in order to cover the whole year?