This past summer’s speaking work led me to a clarification on how I think about the character strengths that hang on my ninth grade classroom wall. This is exciting to me because, while my students tend to engage with the reflective or experimental work we do around helping them grow the strengths, I'm not satisfied with the gap between how I wish it would impact them and how it does.

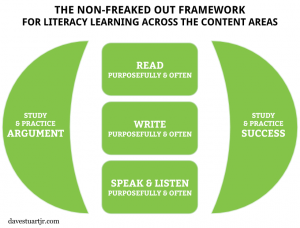

Mind you, I am very thankful for this component of the NFO Approach (see Figure 1), and I can't imagine teaching without investing care and attention into the whole picture of what it is that promotes the long-term flourishing of kids. When I think back on some of the highlights of the past few years, some of the things I've been most thankful to participate in — the kids grappling with a quantity of literacy work that, five years ago, I would have found amazing; the small-town, open admittance APWH freshmen exceeding the national pass rate by 20% — are due in significant part to the fact that, years ago, my colleagues and I decided to look into this character stuff.

Yet the strengths can be hard to hold together in a coherent fashion, and I think that limits the students and me from using them to solve the problems that daily face us. Because, even with the strengths on the wall and embedded in my instruction, the Snowball Kids still happen. The homework completion rates still stagnate. The kids still change so much depending on what classroom or context they're in at the moment.

So here's the question: What hurdles get between our kids and their success? And what does this have to do with character strengths? I think it comes down to two hurdles.

The “Gotta Want It,” Motivational Hurdle

Before a kid can realize his or her potential in my ninth grade classes, he or she has to want to succeed. In David Conley's words, there has to be a level of ownership within the student — none of this “I, the teacher, am not going to allow you to fail” stuff. I'm their teacher, not their savior.

Because motivation is fickle, I think it's wise to equip our students with multiple means through which to marshal their internal motivation and “recruit their will.” [1]

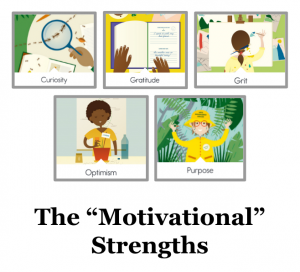

Interestingly, about half of the character strengths on the east wall of my classroom seem to be motivational in nature, helping kids overcome the “Gotta Want It” hurdle. (See Figure 2.)

- Grit (“passion and persistence toward a long-term goal”) is half motivational in its “passion” component: I'm motivated by my passion for X.

- Purpose: I'm motivated by something larger than myself.

- Optimism: I'm motivated by a belief that effort today can improve outcomes tomorrow.

- Growth Mindset (which I really find hard to differentiate with optimism; Growth Mindset isn't on my wall, even though I care about it enough to write about): I'm motivated by a belief that skill and intelligence are incremental rather than fixed.

- Curiosity: I'm motivated by a desire to learn or know something.

- Gratitude: I'm motivated by an appreciation for what I've been given.

If you start picturing the kids in your class who work hard, you start to see that they're not all motivated by the same things. Cabdul, who I wrote about years ago, was a young man driven by Gratitude; Alex, who passed his APWH test last May but in December had the lowest first semester performance in the whole class, was driven by passion; Mullsenhemier, who came into my room every time I offered study hall, was driven by Optimism.

But motivation isn't enough. Many of my students are motivated when we do a goal-setting exercise or I give a Do Hard Things story, and yet too few translate that motivation into success.

So: what gives?

The “Gotta Do It,” Executional Hurdle

You can be the most motivated person in the world, but that motivation must translate into doing the work if it's going to take you anywhere. I'm pretty good at encouraging my kids to think and dream about who and what they want to be; I'm not as good at helping them actually do the work to gain the skills and dispositions their dreams will require.

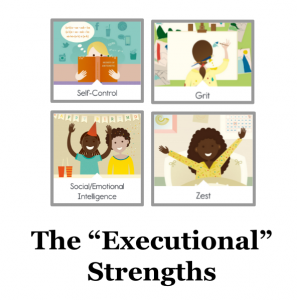

Notice how the rest of the character strengths are executional in nature, nicely suited to help with the “Gotta Do It” hurdle. (See Figure 2.)

- Grit (the persistence component): I persist in the face of adversity; when things get hard, I keep going.

- Too often, this is all people talk about when they talk about grit.

- Self-Control: I control my behavior so that it aligns with my goals. I come prepared. I resist distractions. I get work done first rather than procrastinate. I control my temper. I act politely.

- Social/Emotional Intelligence: I understand my feelings, and this helps me perform appropriately when under stress, feeling down, experiencing excitement, etc. I also understand others' feelings, and this helps me work effectively with peers, teachers, and parents.

- Zest: I approach life with excitement and energy. I actively participate through listening and questioning. I'm an energy giver to those around me.

How much easier would your work in the classroom be if kids fully developed these four Executional Strengths? When we design simple experiments and interventions to help kids develop these strengths, we're working toward, truly, working smarter rather than harder.

The obvious challenge

All I've done in this post is share the way I've come to mentally organize the strengths, and this still leaves us with several big questions. What are the best ways to approach these things, in the context of our literacy-laden, content-rich lessons. More to come soon.

Footnote:

- I love that phrase, “recruit the will.” It comes from Meg Meeker in her book Strong Fathers, Strong Daughters: 10 Secrets Every Father Should Know.

Gerard Dawson says

Dave, two thoughts here I’d like to comment on:

“I’m their teacher, not their savior.”

This is the narrative that should dominate education if we can, as you mention so often, have teachers who do good work and don’t burn out. The desire to constantly improve along with the admission that we can’t do everything is so necessary, especially in newer teachers with grandiose visions.

“What are the best ways to approach these things, in the context of our literacy-laden, content-rich lessons.”

I think we have a special opportunity to approach these things *because* we have literacy-laden, content-rich lessons. We get to use the stories of people doing hard things, trying/failing/persevering, living lives of character as the basis of our classes. While STEM teachers can certainly do the same, I feel grateful that teaching literacy and social studies is somewhat indistinguishable from teaching what it means to be a good person.

Lisa Guardino says

Dave,

Thank you. Once again your post is timely. Approaching parent conferences and this is the theme for so many. I appreciate your expertise, time, and willingness to share. Your work is such a gift.

Lisa

Tim Hartman says

I’m a math teacher sent here by an English teacher at a conference. This is wonderfully insightful! Motivation broken down into wanting and executing; each of those broken down into specific traits; the whole thing linked to character development – mind blown! Academic research on intrinsic/extrinsic motivation is ages behind this framework. Thanks so much. You have a new subscriber!