There is nothing more depressing than spending your weekend grading 125 essays.

Scratch that. There is. The only thing more depressing than spending your weekend grading 125 essays is spending your weekend grading 75 essays because the other 50 didn’t turn them in.

That's Lynsay Fabio, one of our many colleagues in the great field of education. She educates in Louisiana.

It grates at your soul. You think, are you kidding me? How many hours did I spend teaching you this content? Creating and copying the packet of original sources? Holding writing conferences and extra help hours? Taking precious class time to go over the deadline again and again? And you can’t spend 3 hours writing an essay? WHY DO I BOTHER?!

And then you start Googling, “What other jobs can teachers do?” as the pang of failure seeps through your heart.

Lynsay's describing a problem we’re all familiar with: low assignment turn-in rates, where the pain is especially acute for essays.

Call me dramatic, but that’s honestly how I felt every Sunday for the first three years of my teaching career. When I finally mustered the courage to Confront the Stack, the first thing I did was count them. It was always a deeply disappointing number, and it made me resent that time I spent grading even more than I already did.

And that’s just teacher-facing. Think of all that achievement lost when a kid doesn’t turn in the essay. They never gave themselves the chance to solidify the knowledge they’ve built in the unit, and you have no idea what they know or can do, and they are just that much better at not doing work in school. And think of their sense of failure as they walk into school on Friday, knowing that they are empty handed.

Lynsay's story couldn't be a better way to look at today's topic.

There are two critical problems on the line here when we talk about how to motivate students to turn in their essays:

- Our pain and frustration

- Our students’ long-term flourishing outcomes

This ugly cocktail of my-pain-and-their-floundering is why, when I taught in Baltimore, I started using brownies. I don’t even want to count how many nights I spent with Betty Crocker, concocting tomorrow’s bribe, all while blind to the fact that by promising brownies for turned-in essays I was telling my middle schoolers, “Hey — the point of this is brownies.”

Yeah — I'm confessing. I did it — I was desperate.

And guess what? It barely made an impact. And it made me feel gross, like I had cheapened myself and fallen prey to the current culture of appeasing kids and protecting them from having to develop the skills required to complete essays. Not only that, but I had to add the task of “washing out the brownie container” to my task list on Fridays.

So clearly you can see that I’m not a fan of the sugar-based bribe. Brownies or candy is not how to motivate students to turn in essays. We need a more authentic motivator — a more sustainable fuel.

As it turns out, there’s a way better way. Science helps us see what actually motivates human beings to do their best work in the long run. And as I’ve changed my teaching practices to reflect those findings, my students have turned in more essays.

Here’s how to motivate kids to turn in essays.

The most empowering place to start is to look at ourselves.

Do the kids think I’m a good teacher?

This is hard to hear, but science says that kids will do more work for you if they believe that you’re a good teacher. The converse is also true: they will do less work for you when they question if you’re a good teacher. Kids define “good teacher” like this: Do you care? Are you competent? Are you passionate? Our goal is to make sure these things are a resounding “yes” when it comes to turning in essays.

Do the kids think I care if they turn in this essay?

Believe it or not, plenty of our students wonder if we even actually care if they turn essays in. We can demonstrate that care in many ways, but here are a few ideas that I know work.

Abandon the anonymous drop-off location at the front of the room. The next time you have a due date, spend 10 minutes circulating among the desks, picking up each essay one by one, and checking it off your list. Look in their eyes and smile and say, “Thank you, Jamal. Thank you, Sarah.” When a student doesn’t offer an essay, ask, “Do you have your essay today, Kevin?” When they say no, say “I see,” or “OK,” or something neutral or nothing at all. The goal isn’t to embarrass them or guilt them — we just want them to know that we know and care that they haven’t turned it in. Your tone is critical in this moment!

Even if you do digital turn-ins, like via Google Classroom or Schoology, I’d recommend going around the class, laptop or tablet in hand, checking in with each student about whether they’ve turned in their work. This can be done during a writing-based warm-up activity. If the assignment is due before a weekend or break, you could drop a quick email or comment to each one inside the digital platform.

Do the kids think I’m a competent, capable writing teacher?

None of us are motivated to work hard for people who we feel are incompetent at their jobs. Competence, then, is something we model for our students at every part of the essay-writing process.

We demonstrate our competence to kids in a variety of ways. For essays, it’s important that we attend not just to the writing instruction, but also to the introduction and feedback phases of the assignment.

Demonstrate that you are thorough in planning and communicating major assignments and deadlines. This shows kids that you’re a clear thinker. Give them a “Project Announcement” handout on the first day of the unit where you tell them what the final question will be, what the basic requirements are, and when the deadline for the paper is. (I stole this from either Jim Burke or Kelly Gallagher.) Use a consistent template and take an extra minute to make sure it’s free of errors. Do this for every major assignment so they know to expect it. Post the deadline for the essay in the front of the room in the same place, and mention it every day. By the time the essay is due, kids should feel like, “OMG! WE KNOW! IT’S DUE ON FRIDAY NOVEMBER 16th AT THE START OF THE PERIOD!”

Assess and return the essay in a reasonable amount of time with some feedback. Why should they turn it in on time if it’s going to sit in your car for a week? Kids will doubt your competence if you routinely give their work back late or don’t give it back at all or return it without any form of feedback. (If the rules are different for a routine assignment, like AoW, that’s fine — just tell kids what to expect and then follow through. Also, for help thinking more clearly about grading, see pp. 188-197 in These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most.)

Do the kids think I’m passionate about this essay assignment?

Kids need to know that we care about them, as students and as people. But they also need to sense that we actually give a darn about the things we assign. When it comes to turning in essays, kids respond if they know their teacher has feelings about this assignment.

Talk about how much joy and pride you feel when reading their final products, seeing their accomplishments and hearing their thoughts. Show joy and pride when the turn-in rate is good. Show that powerful mix of disappointment + determination when the turn-in rate is low. Keep your heart in it, even when it stings. And let the kids see that.

Those moves to increase kids’ perception of your credibility as an essay-collecting teacher should work on the majority of your class. Once I do that, I’ve found that my turn-in rates improve dramatically and so does the quality of my life.

But what about those outlier kids — the ones who still aren’t turning things in? Here’s a list I go to for help — totally based in the five key beliefs beneath student motivation.

Here’s how to motivate kids who still don't turn in the essay.

No silver bullets, right? So when we do all of the above and they still don't turn the work in, we don't shake our fists at the heavens and lament our sorry lives. No. We say, “All right — what's next?”

Here are some things to try.

Okay, I didn’t turn in the essay. Do you still care?

Some kids are so used to feeling invisible that they don’t think anyone will notice if they do the work. Show them that you will by making this information known to the people closest to the student: the parent or guardian. I typically do this through a simple phone call, but some of my colleagues are tech savvier — they use Remind or other parent-texting apps.

In these communications, the goal is to be supportive, not condemning.

Here’s our colleague Lynsay Fabio again. This is a sample message she sends out:

“Hi there. This is Lynsay Fabio, Corey’s writing teacher at Sci Academy. I’m letting you know that he didn’t turn in his Memoir writing assignment today. He can still get up to a B if he turns it in tomorrow, but it will lose a credit for every day it’s late. Can you please ask him about it when you see him?”

(Note: To save herself time, Lynsay copies and pastes the same text and just changes the names and numbers. She does all the boys first so that she can keep the pronouns the same, then she does all the girls by adding the s- and changing him to her.)

Usually parents are grateful for these kinds of communication — whether you text via Remind like Lynsay does or make a few calls home as I do. Very often I’ll get follow-up from the student the next day, asking for help. I let them know how to schedule a lunch or after-school tutoring session with me, and we’re on our way.

Sometimes, kids feel annoyed by this. “Dude, Mr. Stuart — just let me fail in peace.” In the long run, however, they get that it’s because I care about them.

Do people like me even write essays? Is there a “fit” between my identity and this writing assignment?

Science shows us that kids ask questions of belonging all the time, albeit nonconsciously. If the answer to questions of belonging is not a resounding “yes,” kids often struggle to find the motivation to do the work.

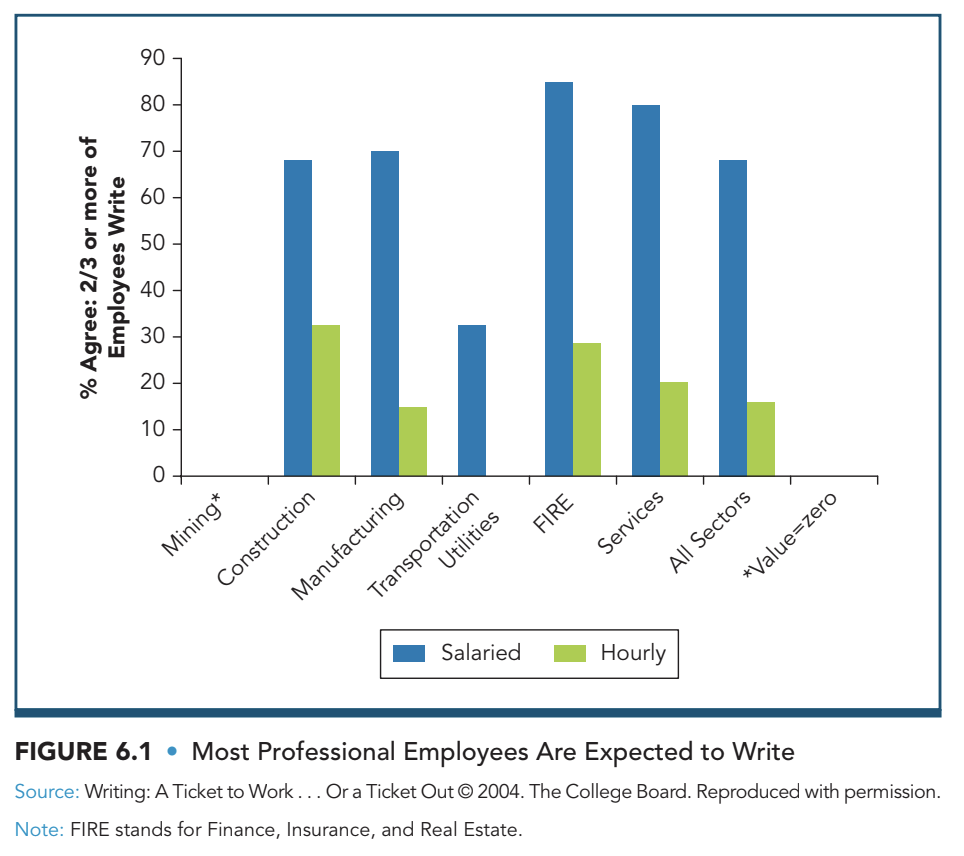

Show kids that writing isn’t something for academics alone. One of my favorite reports to pull charts and graphs from is Writing: A Ticket to Work… Or a Ticket Out. (Below is a reproduced figure from the report that I used in These 6 Things.)

When I have students analyze some of the main points in the report (for example, this year I used this excerpt from the executive summary), it’s amazing to hear them corroborate what they are reading:

- “My mom works at a factory, and she has to write reports all the time and is always complaining that the people who work for her don’t know how to write.”

- “My dad’s a welder, and he says that his boss’ boss has started requiring all the welders to explain how they used their hours each day, for billing.”

Exercises like this help kids to see, “Oh… even ‘hands-on’ people like me need to write.”

Build a brilliant relationship with sports coaches, band directors, and club sponsors so you can offer your athletes and musicians these realistic role models. When the essay isn’t turned in, ask these colleagues to intervene. If you ask them to talk to the student about their experiences in school with writing essays, many will surprise you with their vulnerability and regret in wishing they had paid more attention and had a writing teacher who cared. (And that’s a powerful boost to your teacher street cred right there!)

Can I actually get better at writing essays through my own effort?

Kids ask themselves this all the time. Heck, adults do, too.

Many people are deathly afraid of failure at writing. They will paralyze themselves into not turning in anything because they don’t want it to be bad, and they don’t want to see that big red F at the top of the page.

For our students who are afraid to try, our goal is to teach them that when they feel the procrastination reflex (or the instant gratification monkey, as Tim Urban calls it), the thing to do is to write the draft early and get help with it.

Try this, just with a kid or two, and see how it works:

Set an early-bird deadline for the student, and give him a token of achievement — an extra credit point, an agreement that you’ll sit down and watch those YouTube videos he’s always begging you to watch, a new book for the classroom library — for turning in a full draft early. Send home a positive parent text praising this student’s responsibility. Then give the student 1-2 things to work on before turning the paper in with the class.

That last bit is important — we want the kid to see, “Huh… I can improve through my effort.” So really, limit feedback to 1-2 improvements. More than that, and he’ll question why he tried in the first place. Which brings me to…

Can I actually succeed at this essay?

“Do I have a shot at reaching real success, like an A or a B?” Kids are asking themselves this question when they evaluate whether to do the work of the essay. If they think the highest they’ll get is a D, they won’t do the work.

To combat this, limit the number of items on your checklist or rubric. (I write about the “simple rubric” that I use in These 6 Things, pp. 184-185). They can’t get better at All The Things with this one assignment. Imagine a sports coach who, after a competition, gave his team two dozen things to fix.

That’d be a little too much, right? But that’s often what we do with our feedback on writing or with our grading rubrics.

Give the kids fewer things to focus on so they feel like they can be successful. I’m not suggesting that you lower the standard — my simple rubrics, after all, are modeled after the AP History rubrics, and I use these rubrics in all levels of history that I teach now. Rather, I’m suggesting that you make grade-level success attainable so that kids are motivated to do the work.

For kids who truly have lagging writing skills, have a generous revision policy. They can revise this one thing for a one letter grade improvement. (If you’re doing electronic submissions, you can use Google Drive Revision History to check if they did, in fact, revise that thing, so you don’t have to grade the whole assignment over again.)

Also, have a late policy that gives kids some credit. For me, a paper gets its full grade on the day it’s due, and then loses two points for every day that it’s late. (I think I first learned of a policy like this from Penny Kittle.) And yes, I know that some schools and departments have rigid, one-and-done policies, and I’d rather you keep your job than do every last thing I suggest in this article, so proceed wisely in those cases.

Does this essay matter? Like for my actual life?

Sometimes, we assume that the only way to help kids value a writing assignment is to give them an authentic audience or an authentic writing purpose or an authentic pencil to write it with or an authentic computer to type it on. But authenticity and relevance are only two ways of promoting the value belief in our students. Here’s another one that doesn’t require you to retool your curriculum.

Give kids chances to build connections between what they care about and this particular essay. Literally, go through the Hulleman et al. “Build Connections” exercise with them. Ask them to come up with reasons why an assignment connects to something they care about in their lives.

Again, for some assignments, this is super easy. In one of our school’s courses, we do an informative research paper for which students choose their own topics and gather all their own sources. Choice is one way of making value obvious to kids.

The trouble, of course, is that choice contributes to things like the knowledge gap — some kids learn about all kinds of varied things, thereby getting more and more capable of broad critical thinking and learning. So don’t tell yourself, “Well, every essay has to be choice-driven in order for kids to value it.” That’s not true.

So for others — like this week’s “How barbaric were the Mongols” essay that my world history students are writing — the “Build Connections” exercise is key. At this point in the school year especially (it’s early November for folks reading this from The Future). My students have experienced repeated opportunities to make connections between their lives and the work we do — whether it's essays or pop-up debates or homework — and this has led to them having an easier time doing the work.

Also, have a spiel about how the work of this course IS valuable to living a flourishing life. I always tell folks that my goal is to have 1,000 answers to the glorious question, “When are we ever going to use this?” I want to be able to explain it 1,000 ways because that’ll be a sign that I’ve studied my craft and its implications deeply enough. If this is about turning in an essay, tell them all the careers where writing skills are needed. Don’t talk about careers in general — ask the student what SHE wants to do and tie writing to that specific dream.

The Gist

In order to motivate students to turn in essays without using candy, you have to use something more powerful — you have to use the psychology of motivation. This isn’t something you have to figure out for yourself. Teams of researchers have figured it out for us. We just have to:

- Refuse to accept a low turn-in rate as something to expect as the status quo and out of our control.

- Refuse to harden our hearts toward our students who struggle to turn in work.

- Make sure our teacher-as-essay-collector-credibility is on lock for our whole class.

- Diagnose and act on the outliers using the five key beliefs of student motivation.

- Keep following through and never give up.

It’s not easy. But as Jimmy Dugan says in A League of Their Own, it’s supposed to be hard. If it were easy everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great. And the hard is what makes it true and authentic, changing who kids are and their beliefs about school for the long term, making it much more likely that they will succeed on this paper and the next and the next, and go out there and live a flourishing life that make themselves and their families proud and fulfilled.

And that’s a whole lot better than a packet of M&Ms or a pan of brownies.

alvlgeography says

This is such a beautiful and well thought through article. Thanks Dave! I hope i remember it when i sometimes leave out the outliers

Dave Stuart says

My pleasure — I’m so glad it helps 🙂

Deb Patterson says

Dave, this is some gold in here, my friend. You lighten my load.

davestuartjr says

Thank you my colleague 🙂