In today's political climate, discussions can easily turn into verbal combat.

From Congressional debates to divisive Thanksgiving dinners and angry-emoji-laden Facebook brawls, each voice ends up yelling louder and viler without ever actually listening to the fear and motivation behind the other person's heart.

Unfortunately, the same corrosiveness emerges when we teach argumentative writing to students.

In many places, students are taught a standard model to present their own points and “shoot down” elements of their opposition. While this feels triumphant, especially with a one-reader teacher-audience, it doesn't equip students to communicate in healthy and productive ways.

With a team of teacher researchers—Dave included—I spent time the last few years examining the pitfalls of argumentative writing and crafted methods to teach students to use nuance and empathy to achieve productive civil discourse.

My research scenario (and success!) fell in with the traditional, department-assigned social issues research paper, a staple in many schools. What follows is an approach to teaching argumentative writing that can be adapted for any discipline.

1. Create an Independent Reading “Back Channel”

During your argumentative writing unit, maintain the course with an independent novel reading stream for your students. Do a round of Book Speed Dating where students search for books that are “windows” into lives that differ in some way from their own. Discuss finding an author or main character from a unique identity group (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, immigration status, class, ability, religion). If you teach outside of ELA, try speaking with your colleague across the hall about how the choice reading that is already happening in their room might lend itself to this work.

Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, the “mother” of multicultural children's literature, talks about this now well-known concept of books as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created and recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.”

Once students have selected a book, use natural transition moments in class to invite a secondary conversation about their books. Ask students to briefly check in with their elbow partner. Provide sentence starters to prompt 60-second book chats:

- “I assume this book is a window for me because ____.”

- “Character X and I both think/feel/value _____ because _____.

- “I used to think _____, but now I think ____.” ← One of my favorite thinking routines from Project Zero

These short conversations will ask students to reflect on their relationship with the characters. Talking about identity and perspective might be clunky at first, but this is important seed planting. Students need to practice identifying the values, motivations, and fears of others. This is an essential component of writing an argument that listens.

2. Curate “Heart-Breaking” Social Issues

Bring together an array of social issues as a jumping-off point for your students. Invite vulnerability by asking, “What breaks your heart about the world?” This tender zone is where they should begin.

I provide my students with a non-exhaustive list of issues, and many have been inspired by these resources:

- Amnesty International

- Brookings Institute

- I Side With

- 100 People: A World Project

- Annie E. Casey Foundation (list specific to Gen Z)

Obviously, share the issues that weigh heavy on your own heart and let students talk in partners, small groups, and as a whole class. And don't be surprised by the 1-2 students who cannot choose a topic themselves. They are sometimes swarmed with anxiety about the world or sadly clouded with apathy. Either way, you can always provide them with a topic or they can borrow the heart-breaking topic of a friend.

3. Humanize the “Other Side”

I want this!

Once your students have initiated their research and chosen their stance on the topic, it's time to consider the other side of the argument. Instead of writing “to win” a debate, students must learn to heal the divide by practicing empathy.

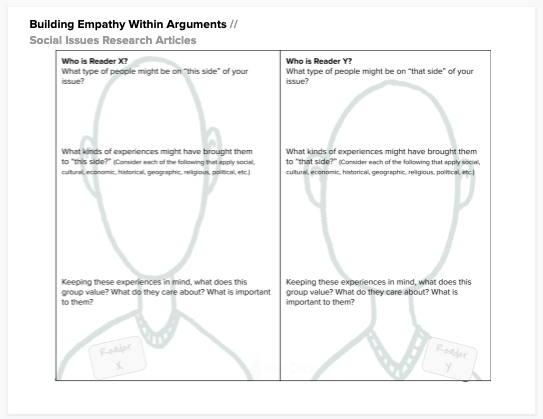

If empathy means “to lean in with compassion,” help your students see the person who sits across the divide from them. I provide my students with the two-column chart on the right.

Ask your students to consider:

- What type of people might be on “this side” of your issue? On “that side” of your issue?

- What kinds of experiences might have brought them to “this side?” To “that side?”

- Keeping these experiences in mind, what does this/that group value? What do they care about? What is important to them?

Aside from writing that has great potential to solve the political divide of our world (no small feat, right? 😉), essays that practice empathy are more dynamic and interesting to read. Remember apathy is a “lack of interest in or concern for things that others find moving or exciting.” When students ignore what really moves their opponents, they erase passion and humanity from their pages, not to mention anything that brings interest to the reader!

4. Provide Models of Empathetic Civil Discourse

So, how exactly do you argue from a place of goodwill? When I began to search for possible mentor texts that model empathetic arguments, I was lost:

I'm kinda freaking out about this project. I have been spinning my wheels with the lack of specific direction or end game. The obscurity of the Listening Argument has me feeling like I'm trying to teach kids how to get through the woods at night without a compass or flashlight. I see it as important work, but I've got no clue how to do it myself, let alone teach it to a group who already struggle with social intelligence…”

– excerpt from one of my real-life, freak out emails to my research partner 🤪

Thankfully, I stumbled upon the YouTube series Middle Ground during one of those late-night wanderings and found my way out of the dark forest! Phew!

In class, select one of the videos to watch together. Before you press play, use the “Humanize the ‘Other Side'” graphic organizer to make predictions about the people on either side of the issue. Then, at various times, pause the video to allow students to add or adjust their original thinking. As with all good teaching: model, think-pair-share, and discuss.

Then, release the students to independently explore videos similar to their chosen topics. This will help them develop a dynamic understanding of the people behind their issue's opposing sides.

Interestingly, my students were most surprised at how civil the Middle Ground participants were throughout the channel. No yelling. No storming off. Nothing like the angry Thanksgiving dinners they'd experienced. We pondered: “What work was done ahead of filming to prepare them for this conversation? How can we prepare ourselves?”

5. Research with “Two Heads”

Once there is an understanding of the human presence on both sides of the issue, follow your normal path for teaching the research process. The shift comes when students begin to analyze the sources from both perspectives. Students need to pivot from just grabbing a quote from each article—if you've taught research writing for more than a day, you know this is standard practice—to actually understanding how the message, the audience, and the communicator are perceived by supporters and opponents of their topic.

I want this!

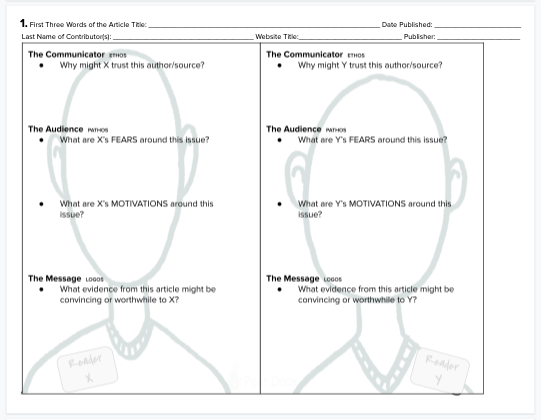

To support this deep thinking, I provide my students with the graphic organizer on the right for each research source.

Ask your students to consider:

- Why might X trust this author/source?

- What are X’s FEARS around this issue?

- What are X’s MOTIVATIONS around this issue?

- What evidence from this article might be convincing or worthwhile to X?

Students were fairly comfortable analyzing the source from their own perspective (X) but grew frustrated when they “couldn't fill out the other head” (Y). They began to recognize that even their research sources sometimes ignored their opponents' perspectives.

Following this alternate approach to research, one of my students who had previously been ironclad on his pro-life stance came in the next day with a visible emotional shift:

“Can you help me? I’m changing my topic, and I basically have to start over now.” He explained that at home the night before, he had been looking online to see how the government supports mothers who are experiencing unexpected pregnancies and realized, “We don’t do much.” He wanted to shift his claim from “The government should make abortions illegal” to a more nuanced “The government should support pregnant mothers.”

-as told by my research partner, Dr. Jen VanDerHeide

While his adolescent heart did not notice this maturity leap, we were amazed at this growth towards creating more nuanced solutions. Soon, other students began to follow suit as they looked at the research from both sides.

6. Model how to Focus on the Values of the “Other Side”

I want this!

From the start, choose your own topic, gather research articles, analyze the sources, then, as you would with any writing workshop, write alongside them.

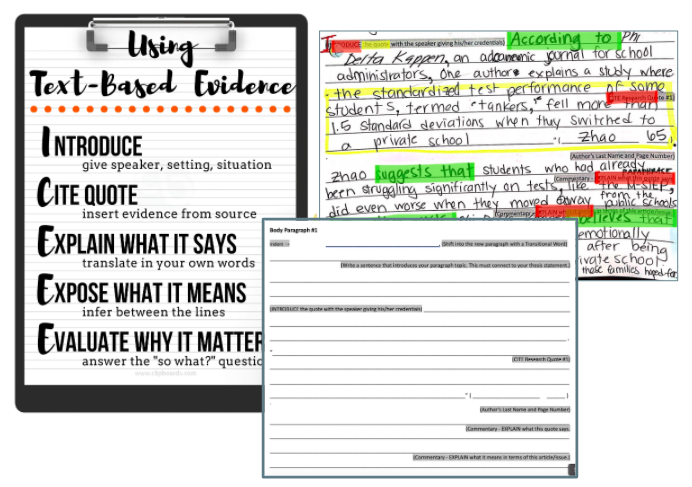

Years ago, I realized that my students needed more scaffolding to transfer the skill of disseminating research analysis to the blank page of their essay. I introduced an ICEEE acronym to support their use of text-based evidence (see our classroom anchor chart on the right). This provides them a sequence they can follow to avoid “quote bombing” (you know, where they drop a random quote into a paragraph and flee without saying anything about it). Still, some students were forgetting necessary components, like in-text citations, transition words, etc. So I crafted what I can only call a “fill-in-the-blank essay” structure to ensure that they don't skip or scramble important components. When I write on the Elmo in front of them, I use this same structure so they can see the moves.

Where these writing workshop steps diverge for a listening argument is in the “Expose what it means” step of the ICEEE acronym. Model for your students how to expose why this evidence is relevant to the values of “this side” and “that side.” Then, address the next-step consequences for the larger audience or issue.

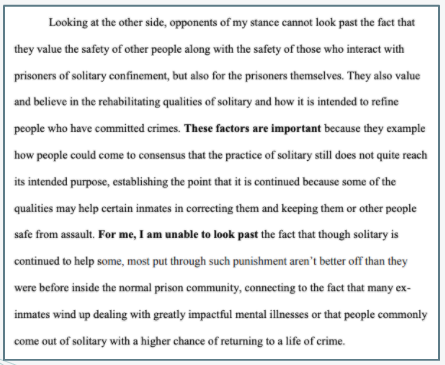

You can see how one of my students attempted this below in the bold-type:

This student also showed great maturity from her original stance of anger and name-calling towards this group of parents.

7. Provide Sentence Starters that Listen

Provide sentence kick-starters to increase writing fluency and confidence. In my handwritten teacher model (shown in the photo above), I highlighted the sentence starters in green, so students could mirror my structure if necessary, filling in with their own ideas and content. Also, in the student example above, you can see that she has used the following empathy-building sentence starters:

- Many ______ advocates value _______, but most don't realize that _______.

- The large majority of people who agree with _______ would not _______ if they knew ________.

These prompts show that the writer is willing to listen to the heart of their opponents and speak to those concerns. This certainly makes the argument more compassionate but more convincing as well.

If you're familiar with my other posts on writing, you know that, like Dave, I'm a huge advocate of providing sentence starters, especially those from Graff and Berkenstein's They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing.

8. Nix the Old “Rebuttal Paragraph“

Today's political divide has grown so entrenched. Gone are the days where televised debates actually swayed voters. Where have all the fence-sitters gone? If they are the supposed audience of a rebuttal paragraph, we need to reconfigure the purpose of this space.

Here's what I propose:

First, introduce a grey area or complication from the other side by showing that you fully see these people and understand the complexity of the issue:

- “The other side believes/values/ fears…”

- “Opponents of my stance cannot look past…”

- Consider using a quote from the other side.

Next, sit side-by-side with your opponents on middle ground. Hold the weight of their belief by emphasizing why their perspective is valid/compelling:

- “This is important because….”

- “This issue especially matters to this group because…”

When teaching this step, I physically pulled two chairs together in the front of my classroom and talked to the imaginary person on the other side of my issue. I picked up their invisible, emotional knapsack and held it in my arms, bearing the heaviness of their heart.

When we shared this section of our rough drafts, this was often the space where peer editors amped up the call for more empathy: “You're not holding the weight of their feels!” “You dropped it too soon. Really show us that you understand!”

Finally, explain what you will do in response. There are two moves here:

1. THE DIVERGENCE:

Discuss how—even while still holding the weight of their beliefs—you still need to carry your stance further towards a resolution:

- “As I have come to understand… , for me, I can’t look past…”

- “Although I can now acknowledge …, I want to move forward by…”

2. THE IMPASSE:

Discuss how you can concede the legitimacy of their claim on this grey area. Recognize that this particular divide is too big to cross given the current state of the issue and will let the divide exist unremedied.

Most students took the Divergence path in their essays. However, one student writing a pro-choice argument chose the Impasse when she realized—after sitting with the other side—that neither group could agree when life starts. Without this consensus, she didn't see this point moving further. Again, we saw great maturity with her including this realization rather than ignoring it and attempting to shoot down a weaker talking point.

Reflection & Recovery

Even if our students aren't watching the latest Congressional mudslinging, they are paying attention to the way the world argues. What is this modeling for our next generation of leaders?

On top of that, we know much of the conflict our students encounter is online in the comment threads of social media. Sadly, they don't always see their opponent as a person IRL. The other person's heart is not an issue they have to deal with. They can choose to ignore it.

We have an opportunity when we teach argumentative writing to turn the opposition back into an actual person. We can teach students to sit right next to their adversary on middle ground. We can model how to figuratively (or literally) hold their opponent's hand and both talk about what we're afraid of or what we value.

We can shift from “winning” an argument to “solving a problem.”

Not only will this make the writing more mature and dynamic, but—with empathy and nuance—our young writers might actually change someone's mind and help heal this divided world.

For more information on arguments that listen:

- NCTE's English Journal published a piece on this particular aspect of the listening argument research project in their May 2021 publication. Look for the title “Making Others’ Perspectives Present: Arguments that Listen.” It is co-authored by Dr. Jennifer VanDerHeide of Michigan State University, Dr. Allison Wynhoff Olsen of Montana State University, and me.

- For other approaches to the listening argument, reach out to my other research colleagues Ben Briere and Jessyca Matthews, who presented alongside me and Dr. Jennifer VanDerHeide at the 2019 NCTE Annual Convention in Baltimore. While very different from my own, their studies produced fascinating and powerful results.

- Check out Raising Student Voice: 35 Ways to Teach Argument Writing from Katherine Schulten, editor-in-chief of The New York Times Learning Network. Schulten invited me to contribute content around my research to her book that “provides teachers with 35 strategies and classroom-ready activities for using… peer mentor texts with their students.”

- Since completing this research, I read and enjoyed the book I Think You're Wrong (But I'm Listening): A Guide to Grace-Filled Political Conversations by Sarah Stewart Holland and Beth A. Silvers, hosts of the popular Pantsuit Politics podcast. I would love to discuss with other readers how this work might overlap and play out in the classroom.

Leave a Reply