Note to readers: This post is an ongoing project in August 2022. I'll be adding to it frequently.

Introduction

When students don't optimally Value school, they'll say things like this:

- This is boring.

- This is pointless.

- Why do we have to do this?

- When will I ever use this in my life?

When they don't optimally Value an assignment, you'll know by sounds like this when you introduce the work:

- “Awww man!”

- “Really!?!”

- “Whyyyyyyy?!”

- “Ughghghgh!”

So here's the deal: that's not something that you just hear in your class. That's a pretty normal thing in a setting like a classroom.

Here's why: your classroom is an alternate world from the one your students normally inhabit. Or at least, it should be.

It's a cosmos — Latinized from the Greek kosmos: a good order, an orderly arrangement; a world.

Whether you teach art or agriculture, social studies or Scripture, English language arts or personal finance, you are, day by day, through helping your students toward mastery of your discipline, inviting them in to a cosmos.

And that, of course, means a bit of discomfort.

It means work.

It means sacrifice and movement.

It means sometimes doing things that, at least initially, will make you make “Urrrghghgh!” noises.

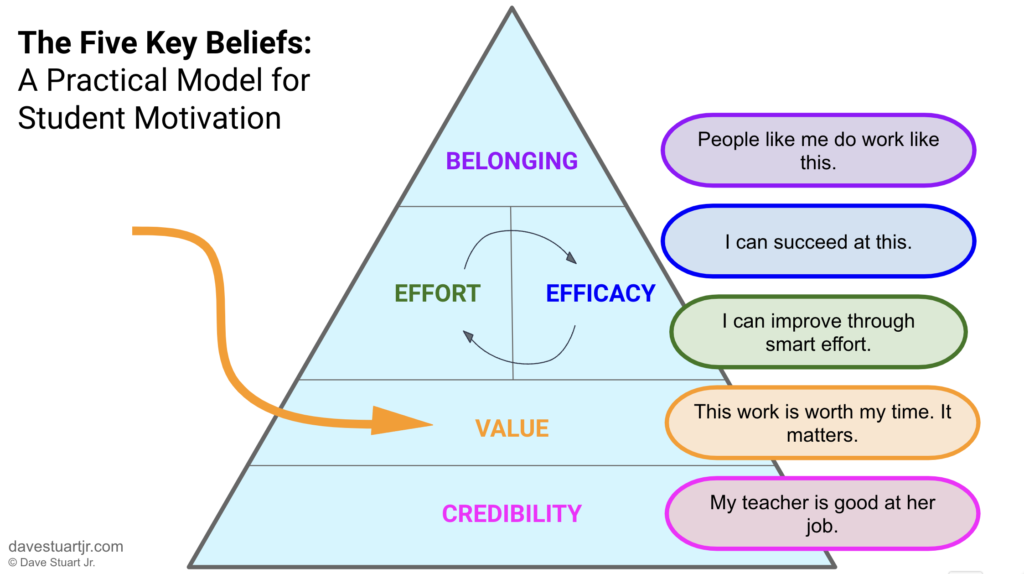

This is where motivation comes in. With reference to those complaints and noises we looked at a moment ago, we're specifically looking at Value — one of the five key beliefs beneath motivated student learning.

Step 1 for Cultivating Value: Have Fun with It

When your students respond to your high-impact lessons with moans and groans, this need not frighten or bother you. There's a way to become so sure of the goodness of what you have on offer in your cosmos that you don't bat an eye when folks are genuinely hesitant about its goodness.

- They don't like writing right now, and you can relate to that: after all, writing is hard and often proves to us how foggy our thinking is.

- But you can still have fun as the writing teacher because you know they'll come round. After all, writing is so many good things. Writing gives you so many things that not-writing can't.

- They're not into Phys Ed right now, and you can relate to that: after all, Phys Ed pulls most kids out of their comfort zones and requires exertion and discomfort.

- But you can still have fun as the Phys Ed teacher because you know they'll come round. After all, Phys Ed is so many good things. Phys Ed unlocks a life of self-growth that not-Phys-Ed can't.

If none of that makes sense right now, keep reading. In the next however many posts, I'm going to share with you examples and strategies for having fun while stoking the fires of Value and moving your students, bit by bit, along the Value spectrum.

An Apologist Winsome and Sure

Caroline Ong's “Math is Beautiful High Horse” Example

My favorite method for cultivating Value in the hearts of your students for the work of your discipline is called “An Apologist Winsome and Sure.”

That's a weird title — purposefully so — so let me briefly explain what I mean.

An apologist is someone who makes a case for something that's controversial. But this summer, I learned a bit more about the roots of the word. It has two parts:

- Appo — meaning “out from, out of”

- Logos — meaning “reason, meaning, order, speech”

A teacher who is an apologist, then, is someone from whom words about the meaning and reason of what you do in your class flow out.

I picture a fountain that's ever bubbling with water, the nourishing stuff of life.

- The ELA teacher who is an apologist for English language arts is like a bubbling brook; he's always nonchalantly crafting these “positive micro moments” (language our ELA colleague David Reese created) in which the class gets to marvel at the wonders of language.

- The personal finance teacher who is an apologist for personal finance is like a bubbling brook; she's always going off on micro-tangents of how cool and neat and useful and meaningful personal finance can be.

- The math teacher who is an apologist for mathematics is like a bubbling brook; she's reliably springing forth with the reason, meaning, beauty, and order of math.

And speaking of math, let's close with a brief video example of what I'm talking about. This comes from Caroline Ong, a mathematics teacher based in Texas.

We'll use this video again as we deepen our grasp of this “An Apologist Winsome and Sure” strategy. But for now, let's agree on a couple things:

- She's giving reasons for mathematics (from point 1:20 in the video until the end) — in other words, she's giving an appo-logos, an apologetic.

- These reasons are flowing out of her in a way that exudes her enjoyment of what she's speaking about — this is winsome — and her confidence in it — this is sure.

I want you to do two things with this:

- Go have a ball briefly ranting at times about how beautiful and lovely and powerful and cool your discipline is.

- Do this as often as you can. You want it to be normal for your students to see An Apologist Winsome and Sure — not the exception, but instead the rule.

Going Deeper with Caroline's Example: In Her Own Words

Now's a good time to let our colleague Caroline Ong give us a bit more context on what she's doing when she takes these opportunities to micro-rant to her students about how lovely and important and useful and beautiful her discipline is.

Howdy Dave. I'm glad that my sermonizing about the beauty of mathematics (she is, after all, the queen of the sciences!) is useful outside of my classroom, and perhaps some colleagues will be encouraged to keep doing good work.

So. The horse [that I'm referencing in the video] is completely an incorporeal horse. 🙂 I am a great fan of using analogies to illustrate and teach — my “high horse” is when I want to pontificate about some sort of bigger idea not directly related to the mathematical lesson of the day. (“I'm going to go get on my ‘math is awesome high horse'!”)

Sometimes, I also refer to this as the “free lecture.” There's the lecture you pay for — the math lecture — and then there's the philosophical lecture about the importance of mathematics, or how to be a good student, or how to study / learn effectively, or any other number of topics, that you get for “free.”

[When I'm getting on my ‘math is beautiful high horse,'] I'll generally just step aside from my usual lecture spot — just a different spot from where I typically deliver instruction. Being a creature of habit, my pontificating generally happens in the same spot, too, over to the side. (At least I try to step aside from my lecture when I do this just to give a signal that the next bit will be “different”.)

I wouldn't say that I do this [math is beautiful high horse] on any sort of schedule. It's just when it seems needful or appropriate for the moment.

Feel free to use the video in whatever beneficial way you like! I hope it's helpful! Any more questions, feel free to ask. I love learning from other teachers, and if there's some small way I can contribute, I'm happy to do it.

Let me close with a few things I notice in Caroline's words:

- That intentionality of doing the same things from the same spots is sharp. She gives direct instruction from one spot; she does her “math is beautiful high horse” work from another.

- Her generosity of spirit. This is a person who shared with me (and through me, you) this unpolished glimpse into her classroom for the sake of contributing to a profession that's given her so much. I love that.

- Her “free lecture” concept. Notice that she teaches her students anything that they need to be successful in her class. She doesn't assume they know how to study; she teaches them how. She doesn't assume they know how to learn effectively; she teaches them how. This is so important for so many of the five key beliefs.

Now, go put some of these great things into your practice regimen, colleague! It's good stuff. It's so basic, but so good.

The Rainbow of Why: Go Jackson Pollock with Those Colors

I now want to shift our focus from Caroline Ong to Jackson Pollock.

Wait… Jackson Pollock?

Yes.

This is a standard example of a Jackson Pollock painting:

It's one of the pieces that a non-artsy person would probably respond with, “Wait, why is that art!?”

But here's what I see:

- It's bold.

- It's counter-cultural — this thing was made in 1949, about the same time cookie-cutter communities like Levittown were becoming popular.

- It's energetic.

- It's got this “made-on-the-fly” feel to it (Jackson called it an “action painting”).

These descriptors, to me, have a lot in common with what Caroline Ong is doing in her classroom with what I call the Rainbow of Why.

The Rainbow of Why

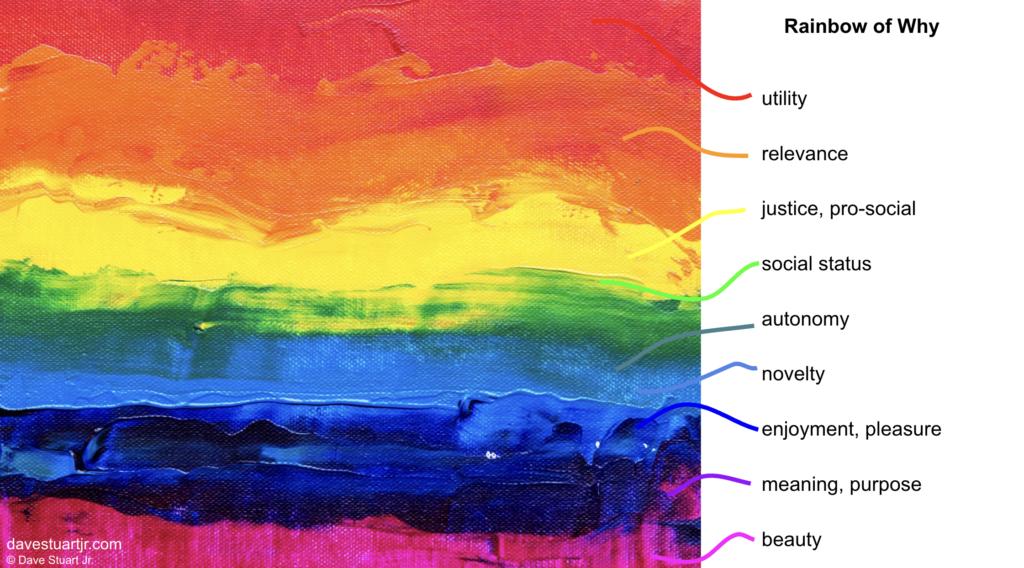

What follows is a diagram I use when visiting with teachers to illustrate just how many ways there are in the research for coming to Value something.

There are a few main points I want to make about this Rainbow of Why:

- You'll move students best toward Value when you intentionally use all the colors. In American education, we tend to paint way too frequently with utility — when and how is this lesson useful — and relevance — how is this lesson relevant to my particular self; overuse of these two colors trains some of our students into becoming unhelpfully self-focused.

- This is a painter's palette for a reason — I want you to view Value cultivation as a creative work, an exploratory work, a beautiful work; not a have-to, a get-to; not a job, but rather a joy.

- And finally, I want you to paint with these colors like Jackson Pollock; be bold, be counter-cultural, be energetic, be okay with “on-the-fly” action painting.

Youthful Purpose Guru Bill Damon’s “Golden Opportunity”

Now let's turn to one particular simple, research-backed method for developing a sense of purpose in young people. This will help us see how simple it can be to paint with one of the most powerful colors in the Rainbow of WHy.

There's this researcher out of Stanford who basically dedicated his life to studying why some people enter adulthood with a strong sense of purpose and others don't.

His name is Bill Damon. I'm sure most of you have heard of him. For those who haven't: you're welcome. What a heart for young people this man has built in his career. And what a mind.

But today, I just want us to focus on one little idea that Dr. Damon gave us. One little thing that, if he could wave his magic wand and ask all teachers in the world to do just one thing consistently, he'd advise us to do.

I'll turn it over to what Dr. Damon once wrote in this article for the AASA:

One golden opportunity to [give young people purposeful role models] is for teachers to tell students why they chose teaching as a profession, what they find fulfilling about teaching and what they hope to accomplish with their students. The point of doing this is not to persuade their students to become teachers but rather to show what it looks like for an admired adult to pursue a vocation with purpose.

If you've got a five minutes, check out the video below in which I give two examples of what this can look like. If you don't, I'll share the relevant language below the video.

A longer example of what this strategy sounds like with students:

Hey there, students! How in the world are you guys doing today? You know, I was driving to work today, and I was thinking about you, and I was thinking, “I'm so glad I get to be your teacher.” Here's what specifically spurred the thought. I was remembering back in my freshman year of college, when I was studying Pre-Med, I was training to train to become a doctor. And basically, I got to this point where I was shadowing doctors to make sure that I wanted to be a doctor someday, and I remember that this doctor said to me, “Listen, young man. You better like what you just observed me doing because that's gonna be your life.”

It was a very striking moment for me because I didn't really like much what I had seen the doctor doing, and I wasn't really interested in medicine like I thought that I would be. It was kind of like a crisis moment for me because I had told all these people as I was going off to college that I was going to be a doctor, and now I was changing my mind.

So it was a few months later when I went to a Boys and Girls Club in Chicago, and I got to work with all these young people there at the Club, and I just suddenly realized, “Wow, this is really cool; I really like to work with young people; I really like education; I like getting to build into others; I like history, I like reading, I like literature, I like writing. Why not just mix them all together and become a teacher?”

And you know, my journey with teaching has had its ups and downs. Teaching has a lot of things about it that are really difficult, a lot of things about it that I definitely have to get paid to do, but you know what? It's awesome. I like doing it and I like getting to do this year's teaching with you. So, I just want you all to know I appreciate you. Thanks for letting me be your teacher

All right, now let's get to today's lesson.

A shorter example of what this sounds like with students:

Hey students, when I was watching you all do that reading right there, reading that article during the lesson — I know, I know, we only have another minute left, but please just bear with me — I really got to thinking how amazing it is to watch you read and interact with so many different sources on so many different days all across the school year. You've just kind of inspired me, and I want you to know that I've always been thankful to be a teacher, but especially today. Especially today, I'm glad I get to be a

teacher.

And now, go to it! Make a note to yourself to try this out with your classes ASAP.

And don't be afraid to do it multiple times throughout the semester, in ways big and small.

And finally, have FUN doing it. Because it IS fun to get to be a purpose exemplar for young people.

Waiting on Stars (Or You’ve Never Met a Student that Wants to be Demotivated in School)

Here's a thing I don't think we think about enough:

Your students WANT to be motivated.

This is something fundamental to human beings.

So, this is what I contend: you’ve never met a student who set out to become demotivated in school.

Every. One. Of your students, down in the roots of their will, desires to desire to learn.

That word desire is important to contemplate.

It's from the Latin desirare, with De connoting from within, deep down, and sidere meaning “from the stars.”

That’s a weird word, right?

Etymologists surmise that, originally, the word meant something like, “to await what the stars will bring.”

To await what the stars will bring?

Daaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaang.

That's deep.

So listen, look out on your classroom tomorrow, and see deep in those eyes an unyielding desire to desire to learn.

See an awaiting what the stars will bring.

Because that's what's there.

Warren Roth says

This entry is absolute 🔥. How do you feel about the Rainbow of Why being a visual focal point in one’s classroom? Is it too “teacher talk” or would it benefit the students? I often share with them my “why” even if it does seem like teacher talk.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Cheers Warren! I’m very glad. I’ve heard of teachers experimenting with making the Rainbow of Why student-facing. I have not yet, but I think it’s an interesting idea. I’d say, follow your gut.