Last time, we established some basic insights from the literature on resilience: it's a thing; it makes our lives better; it's a lot like the serenity prayer popularized by twelve-step groups like Alcoholics Anonymous.

Resilient people are characterized by three tendencies:

I. Acceptance of reality (treated below)

II. A strong sense of purpose (treated in this post)

III. Adaptation when things change (treated in this post)

Today, let's examine acceptance of reality.

Step 1: Repeat after me: “Reality is real, and teaching is hard.”

Seriously, Dave? You're wasting my time with this?

Breathe.

The hard thing about teaching is that it's hard. It is, in many moments of the day, work. And the reason this is hard is because many of us entered the job thinking it'd be one of those, “If you love what you do, you'll never work a day in your life” kind of things. But teaching is just like gardening or doctoring or being a mechanic: no matter how much affinity you have for the work, no matter how desperately your heart clings to the three loves of teaching, there are still papers to grade and bureaucratic hoops to jump through and impossibly long hold times to endure when trying to get a consistent answer from your state's Department of Education about whether or not the online master's degree you're considering is going to “count.”

And, you know, angry parents, hurting kids, troublesome colleagues… there are just a lot of thorns in the work.

If we're not resilient — specifically, if we haven't internalized the idea that some things are negative realities that it does us no good to fixate on — then these harsh realities will drown us in pressure.

Let me elaborate on that.

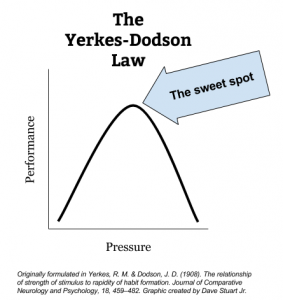

In virtually every school I visit, I meet teachers all across the Yerkes-Dodson spectrum of pressure (see figure).

A few of them are not pressured enough — they've disengaged and checked out. They're coasting.

But most of them are on the other end: they are stressed to the breaking point, and it's costing them their health, their family, their sanity, and (ironically) their performance. Despite their red-lined levels of stress and striving — and actually because of these high levels of stress — they're not able to do as good of a job as they could do were they to do the work in less stressful conditions.

You see, too much pressure costs us twice: it lowers our performance — the quality of our work — and it lowers our flourishing — the quality of our lives.

So the first step is literally to remind ourselves, daily, that teaching is hard. Some of you are reading this and thinking, “Dave Stuart is an idiot. Why is he writing this?” And others of you are reading this saying, “Ohhhh. Wow. I needed to hear that.”

(The second person is my target right now.)

Dean Becker of Adaptiv Learning, who we met last time, illustrates my point. I see what Becker describes in faculties across the world:

Very often we find individuals, especially in high-tension settings, beating their heads against problems over which they find they have little or no control, but on the other hand missing opportunities to solve problems when they jump to the conclusion falsely that there is nothing they can do about it.

Step 2: Identify what you can control

The core competency of this part of resilience is being able to differentiate between what you do have agency over and what you don't. What can you change, right now today? What can't you?

Students with hard home circumstances–

Can't control: the home lives of my students; the past circumstances of my students

Can control: how I treat students; how I respond to signs of trauma in my students' lives; how frequently I connect with my students

A giant pile of papers to grade–

Can't control: the department-mandated rubric I have to use

Can control: my instruction around the writing assignment; the amount of time I spend grading each paper; the kind of feedback I give students; the turnaround time on the feedback I give (biasing myself toward quickness vs. thoroughness)

A colleague who glares at me with eyes of death every time I see her–

Can't control: what the colleague does; what the colleague might be thinking of me right now

Can control: my interpretation of what the colleague does; the degree to which I allow myself to fixate on what the colleague might be thinking of me; whether or not I speak to the colleague directly to see if I might have done something to bother her

(Here's a whole post on working better with colleagues.)

When we start sorting work circumstances into buckets of what we can control and what we can't, an inexplicable joy develops. What is that feeling? It's a renewed sense of agency. There's stuff I can do! I'm not stuck!

And that is a bit of what resilience feels like.

So here we stumble on a discipline for ourselves: When we feel overwhelmed or especially defeated, we can list what we can control and what we can't.

Case study: Viktor Frankl's insights from a Nazi concentration camp

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who survived the Nazi occupation of Austria. Just as he was starting his medical career, the Nazi takeover of his country led to the rapid loss of his rights. Frankl was deported to a Czechoslovakian ghetto in 1942 and then to Auschwitz in 1944. A key moment for Frankl came when, at Auschwitz, he decided to “imagine himself giving a lecture after the war on the psychology of the concentration camp, to help outsiders understand what he had been through. Although Frankl wasn't even sure that he'd survive, he created some concrete goals for himself.”*

“When we are no longer able to change a situation,” Frankl writes in his classic Man's Search for Meaning, “we are challenged to change ourselves.” And within challenge, of course, can come purpose — assuming that you desire to live a life where you are doing hard things.”

Later on in the book, Frankl writes that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

What's the point, as it relates to us and our work in education? We face nothing near as evil as the Final Solution. (It's absurd for me to even write that sentence.) But like Frankl, we can cultivate a sense of what we do control in our daily work and what we don't. We give all our effort to the latter bit and as little as possible to the former.

Step 3: Harden your optimism

Frankl's insights remind me of something in the classic, not-at-all-about-education-but-more-relevant-to-education-than-most-books-on-education book by Jim Collins: Good to Great.

(I wrote about Collins' interaction with Peter Drucker a while back; that post differentiates success from usefulness, and it's here.)

Collins tells the story of Admiral Jim Stockdale, who survived a Vietnamese prisoner-of-war camp for eight years. Interestingly, Stockdale says that unbridled optimism was the top predictor of whether his fellow inmates would survive.

You see, Stockdale was certain that he would “prevail in the end.” But he says that this certainty alone was deadly. It was the combination of his optimism — “I will prevail” — and his realism — “I am in hell” — that he says made the difference for him.

“They were the [fellow inmates] who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

Stockdale was convinced he'd get out, but he was simultaneously convinced that it'd be in a terribly long time. He calls this “confront the brutal facts.””

This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

The Gist: Quick tips for building resilience

When things start bothering you, sort circumstances into what you can control and what you can't. We discussed this above. It helps. This is my favorite tip.

When something unexpected happens that threatens to ruin your day/week/month, respond with, “Well, of course it did.” Talk yourself into why it actually makes sense that things go wrong.

Examples:

- When a student shows you a poor attitude: Of course this is happening. I'm not the omnipotent deity of their life. I'm only with them an hour a day, five days a week. I wonder what's going on? I can follow up tomorrow.

- When you forget to go to a meeting you were supposed to attend: Of course that happened! I need a better system for remembering things like this. I'm going to try something new for that starting tomorrow. If I need help, I'll even spend some time tonight brainstorming with a friend. And I'm also going to make a call to [person in charge of meeting] so that I can apologize. It might be uncomfortable, but it's the right thing to do, and it'll raise the stakes for me to do better in the future.

- When you get an angry parent at conferences: Of course that parent was angry! Who knows what stressors exist in their life. Who knows what weights they are carrying around on their hearts — of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and so on. Life is difficult. I wonder if my grading policy is clear enough. What part of their anger might actually be giving me a hint into how I could improve my class for all students?

- When a student is unmotivated: Of course they're apathetic about my class! I bet [insert video game] is much more interesting than English 9. I'm going to go back through the Student Motivation Checklist to see if there's something I can try tomorrow.

The goal is to view the things that don't go according to plan as certainties, not exceptions. They're facts of our professional life working with humans in complex systems — not weird instances of fate out to crush our dreams.

When you get too many tasks, non-emotionally sort them by importance. Ask yourself: Which of these are most likely to impact the long-term flourishing of young people? Which are furthest? The furthest ones get satisficed or skipped. The closest ones get your best hour — early in the morning before school, your prep period, right after the kids go to bed.

The non-emotional part is important, and it's easier for some of us than others. This is why the internal work is so important. Sometimes we make our bulletin boards fancy because we want people to respect us, or we like what it looks like when we post it on Pinterest. But the physical classroom environment is low on the list. Bulletin boards are often more about us than they are about kids. (Often, not always!)

When you're in a super hard situation — too much to do, really difficult class, terribly negative colleagues — acknowledge those facts repeatedly while simultaneously reminding yourself of why you're here. I frequently remind myself of the things that make my job very challenging. For example, more than fifty percent of my ninth grade students have smartphones, and I am convinced that this is terrible for their hearts and minds. I remind myself of this and the research that confirms it. But I nonetheless remind myself that I am here to promote their long-term good.

Every day, that's the job, and it's quite doable. It's almost impossible to not promote the long-term good of young people every day once your mind is set on doing it.

We'll talk about that more next time.

UPDATE: Here's the whole series:

- Teacher Attrition, the Serenity Prayer, and the Resilient Inner Life

- How to Build Resilience, Part 1: Acceptance of Reality

- How to Build Resilience, Part 2: A Strong Sense of Purpose

- 500 Blog Posts: A Case Study in Resilience

- How to Build Resilience, Part 3: Adaptability

- A PS from much later: The Two Rules of Resilience

*from Diane Coutu's “How Resilience Works,” for the Harvard Business Review.

Lisa Coyne says

Oh man! In a culture that coddles, protects, and celebrates participation as a victory, THIS is a very important message. Thanks for this post!

Ms. Campbell says

I want to push back on the idea that physical classroom environment isn’t very important. For me, it is. I spend more (or at least a large portion of) my waking hours in my classroom than I do anywhere else. Being in a physically comfortable space helps me feel more productive as a teacher. And if teaching is about making sure we are our best selves at all times for our students, helping me feel productive and organized is a way I do that. Aren’t I just building my “long term flourishing”?

Now, don’t get me wrong. Pretty classrooms do NOT always equal highly productive learning environments. However, my “pretty” classroom sends a message to my students: that I enjoy being there enough to make it my own and that I value taking time to make space for a learning community. I also love that through my classroom decoration my students learn more about my interests/personality.

I’m very curious to hear your thoughts!

davestuartjr says

Ms. Campbell, you bring great points up here. A couple of thoughts:

–physical classroom spaces aren’t of zero importance, they just aren’t as high on the list as effective lessons, cultivating the five key beliefs, and things like this. Some of the most effective classrooms in the world are very minimalistic — see the Dan Coyle reference in my blog article here: https://davestuartjr.com/physical-classroom-environment/

–our goal isn’t to feel more productive — it’s to *be* more productive. More productive of what? Of the kinds of things that promote the long-term flourishing of our young people. The LTF of our young is what teaching is about — not making sure we are our best selves at all times.

–now with all of that said, some of the best teachers I know have beautiful classrooms. And, some of the best teachers I know have the most boring classrooms I’ve ever seen. All that this means to me is that the physical classroom environment isn’t nearly as important as the psychosocial (I’m not sure if that’s the right word) classroom environment. As you say, your physical classroom environment *contributes* to that more important layer of the environment.

Thanks so much for the sharpening push!

Ms. Campbell says

Dave, I went and read your post about physical classroom environment, and I now better understand what you are saying. And I TOTALLY agree – a pretty classroom means nothing without a productive learning environment. Physical space is only one piece of a very large puzzle.

But, don’t we have to be our best selves as teachers to be more productive – to promote the LTF of our students? (Not just feel more productive. An important distinction you made!) If, I as a teacher, don’t feel like I can flourish in the long term as a teacher, am I being a very productive model for my students?

As a teacher in training, your blog is one of the most helpful I have come across! Your book is at the top of my PD pile to start as soon as I graduate!

davestuartjr says

You are asking all of the right questions, Ms. Campbell, and I am so thankful that you are here considering these things at such a ripe time in your career — the beginning 🙂

We want to be cultivating PERMA in our lives (https://davestuartjr.com/perma-flourishing/). Great teachers tend to lead great lives. If you and I aren’t doing the things that promote our own long-term flourishing, I do think there’s a short shelf-life on our impact. So to answer your question: no, you are not. If you’re stuck in frustration (or in a frustrating physical environment), then you ought to do what you can to remedy it. (James Clear writes well about the importance of environment: https://jamesclear.com/environment-design-organ-donation

I’m so glad you left your comment. Keep on doing what you are doing. Many young people will benefit from your work.