It was the first day back from winter break, and after students completed their written warm-up, I started class like this:

When I was in high school, I remember one summer break when I worked for my stepdad selling Little Debbie snack cakes. The way it worked was you'd drive this big truck from grocery store to gas station to grocery story to gas station, and at each place you'd go inside, look at the Little Debbie display, and calculate how many new Little Debbies the display needed. You'd then go back into the truck, type into the old-school computer how many cases of snack cakes you were selling to the store, print the invoice, and stack all the cases you were selling onto this cart thing. And then you'd haul the cases in, stock them on the shelves, and head off to the next store.

You did this a dozen or two times per day, every day of the week. It was like a seventy-hours-a-week job, and the cases got heavy, and it was super hot out most of the time. And so at the end of those weeks you'd just go home exhausted.

But I can remember this moment at some store when my stepfather and I were loading up cases when I was telling him about how I was going to start that next school year as a much better student than I had been the year before. He asked me what specifically I was planning on doing differently, and I told him.

And I think this was the tiniest, tiniest start to me being the kind of person who seeks to get better and smarter as a student. This scrawny high school kid loading cases on a cart telling his stepfather his plans for getting better.

So what I'd like you to do right now is to take your warm-up — which is all about improvement — and I'd like you to summarize it for your Think-Pair-Share partner. After that, we'll share out.

Storytelling is useful. It engages kids — people, really — in a way that few strategies do. There's something about the human mind that gears it to attend to stories.

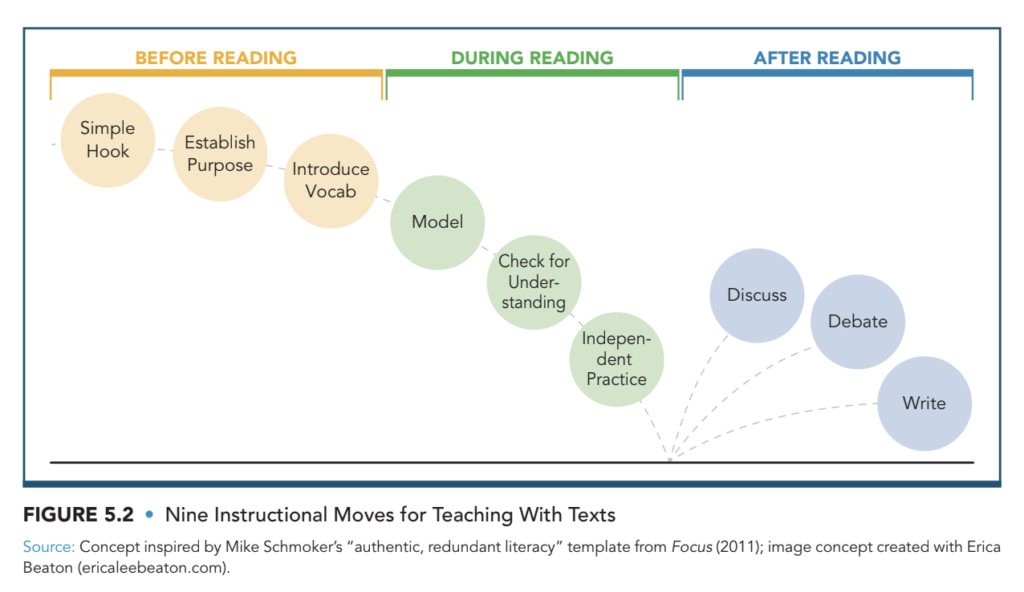

In the reading chapter of These 6 Things, I advocate for a drastically simplified approach to teaching with texts. I think you're smarter to become a master at nine high-impact reading instruction strategies than to become mediocre at nine hundred. I think this because I've seen it in the literature and I've vetted it in my own practice. It's a low-stress means to gaining mastery as a teacher who teaches with texts. Here's a figure from the book that summarize the nine key moves.

Storytelling is a “simple hook” strategy that I don't talk about in the book. But storytelling has been on my mind for two reasons recently.

First, there's Ira Glass. If you're a podcast fan or a longtime NPR listener, you probably recognize Ira Glass' name. He's one of the folks who helped make the Serial podcast happen, and he's been producing This American Life for a couple of decades. I don't have much of a commute so I don't listen to too many things, but I took note of Ira Glass when I came across some of his tips on storytelling. I was interested because I've noticed how engaged a simple story can make my students, and I wanted to leverage the skill of storytelling to get them to do more reading and writing in my class. I also wanted to get better as a storyteller because I'm getting more keynote invitations than I have in the past, and great stories make great keynotes.

All of that's a long-winded way to say that when I found a piece on Ira Glass' thoughts on storytelling, I was ready to read it. Glass has invested his life in being a good storyteller, so what he has to say on storytelling is costly.

So first: Why do stories produce engagement? Here's Glass:

No matter how boring the material is, if it is in story form… there is suspense in it, it feels like something's going to happen. The reason why is because literally it's a sequence of events…. You can feel through its form [that it's] inherently like being on a train that has a destination… and that you're going to find something.

And second, what are great stories basically made of? Glass points to two “building blocks:”

- The anecdote, which by its sequential nature acts as attentional bait.

- And reflection, which takes the story and makes it meaningful or draws from its key concepts [1].

Once you internalize these two components, you start to see them all over the place. For example, in Tim Urban's great TED speech on procrastination (which I use in this lesson), he's telling us stories about himself in grad school and about himself preparing for his TED talk, and as he tells the stories he's introducing his concepts of the instant gratification monkey, the dark playground, and the panic monster. (It helps, of course, that Urban is funny — but humor is a topic for another post.)

In the story at the top of this article that I shared with my students, we see the anecdote — me working on a truck with my stepfather — and the reflection — me looking back and realizing this was a moment when I discovered the power of caring enough about improvement to talk and think about it.

And the second spot where I got to thinking about storytelling was in a little, smart book — more of an essay, really — by novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called We Should All Be Feminists [2]. In the piece, Adichie constantly moves between storytelling — about her childhood friend Okoloma, who was the first person to call her a feminist; about her primary school years in Nsukka; about an incident from when she tipped a parking attendant with her friend Louis — and reflection. One moment, you're intrigued by the imagery in her storytelling — “in the evenings when the heat goes down and the city has a slower pace” — and the next moment, you're laughing as she explains the feedback that led her to label herself not just a feminist, but a Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men And Who Likes To Wear Lip Gloss And High Heels For Herself And Not For Men.

Throughout, Adichie uses her stories for a purpose: to get you to engage her claims. At one point, she argues “that we spend too much time teaching girls to worry about what boys think of them… but the reverse is not the case.” At another, she claims that to be a feminist is to be “a man or a woman who says, ‘Yes, there's a problem with gender as it is today and we must fix it, we must do better.'” And whether you agree with Adichie or not at the essay's end, one thing is certain: you've heard her. You've listened. You've brought effortful engagement to her ideas more than you would have had she neglected storytelling.

And that's the point. We want our kids to do as much work as possible while they're in our classes, with as much effort as we can help them marshal. That's the whole goal of student motivation — do work with care.

Storytelling helps.

Footnote:

- Here's a site with some video clips of Glass discussing more on the art and science of storytelling.

- You may recognize Adichie's name from her popular TED talk, “The Danger of a Single Story.” She's a prolific author.

Dorothy Iorsase says

Thank you…I learnt so much especially as a teacher/Librarian which will help address issues such as ..Lack of seriousness to academics.