Boring. Dumb. Pointless. Irrelevant. Annoying. Stupid.

When students say words like these, they're telling us this: I don't value this kind of work.

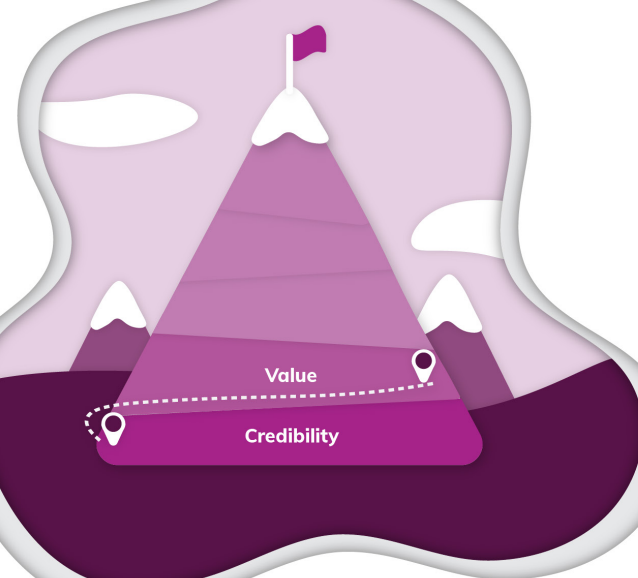

Value is one of five key beliefs beneath student motivation, and the only belief that I've found to be more powerful than it is Credibility (my first weeks of school guide on that here). When we talk about Value today, we've got to realize first and foremost that Value is a real-deal powerbroker in the heart of a human. If a person doesn't value physical education or biology or reading, why do they care if they belong? Why do they care if their effort can pay off? Why do they care if they'll succeed?

Did you miss the intro series? It covers important territory for maximizing the five key beliefs in your school and classroom. Take a look.

- Part 1: On the Teaching of Souls

- Part 2: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Part 3: Five Critical Qualities about the Five Key Beliefs, in Order of Actionability

Never miss an article again! Subscribe to Dave's weekly newsletter, and be the cool colleague forwarding sweet articles to the team.

So I like to think of Value as having it's own special tier in the five key beliefs hierarchy, just a click away from Credibility. That's why, in the mountain image below, Value is a little darker shaded than the remaining three.

In this article, let's look at two things:

- I. Important Characteristics of the Value Belief

- II. Three Strategies for Cultivating Value in the Classroom

I. Important Characteristics of the Value Belief

All right — so when we say “Value belief,” what do we mean?

What it sounds like in the heart of a student [1]

- This work matters to me.

- This is important.

- This is interesting.

- This is meaningful.

- This will pay off.

- This is fun.

So… that's a lot.

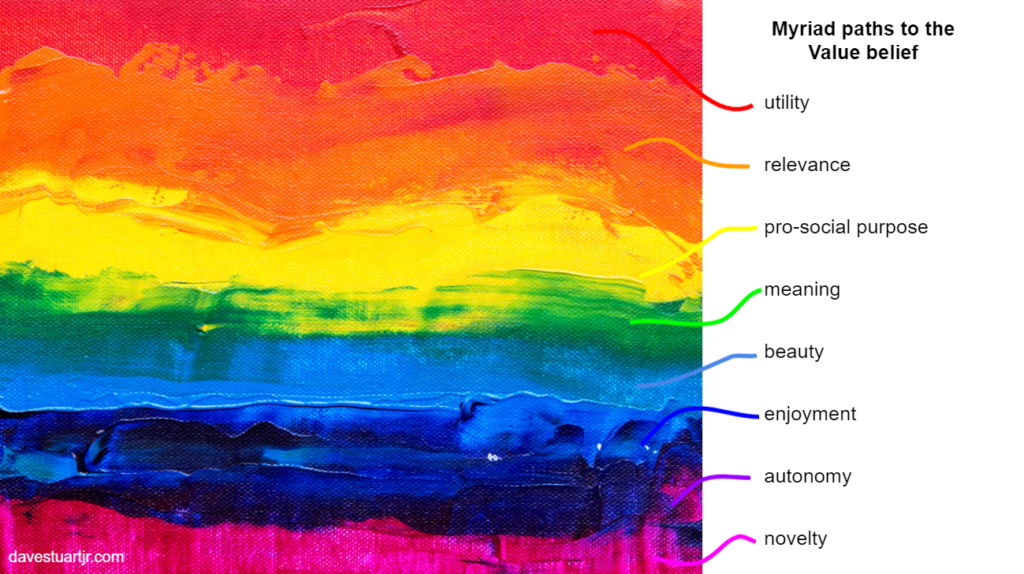

Yes, exactly. The cool thing and the hard thing about the Value belief is that human beings have all kinds of ways of arriving at it. I might value this thing because it's useful or will be useful, this thing because it's super interesting, and this other thing because it provides me with a deep sense of meaning.

This is why I think of the Value belief as a rainbow — all the colors are in them. Rainbows symbolize hope, and the Value belief gives my students and me a ton of hope that there's always a way to turn the work of mastery into something that can matter to each of us.

Here's a key thing: don't monochrome your approach

The thing with Value is that, since you've got such a diversity of hearts in your room, you want to play toward as many of the different paths as possible. Unfortunately, this is contrary to a lot of advice out there about student engagement and motivation because much of the popular advice emphasizes only one or two paths to value.

For example, relevance is a super common angle toward the Value belief nowadays. You might see:

- a teacher leading the class in a close reading exercise of a song that's popular right now, or of a TikTok (old man shudder);

- an assignment in a world history class where students select a figure they've learned about recently and make a Twitter profile for her;

- a teacher working hard to stay up on teen culture so that he can make connections between what's hip and what we're doing in class today.

None of these are necessarily bad, but I do find that it does harm to a student's heart when they spend years with people who seem obsessed with making learning relevant to them. What I mean is that I think over-playing relevance can, over the years, warp a child's perception of the world into a place that, when functioning correctly, makes its demands clearly relevant to them.

Education philosopher Charlotte Mason back in 1886 made a cool observation about this: “[The teacher] should know how to incite the child to effort through his desire of [praise], of excelling, of advancing, his desire of knowledge, his love of parents, his sense of duty, in such a way that no one set of motives be called unduly into play to the injury of the child's character” (Home Education, Vol. 1, p. 141). It's that bolded part that provokes me — that cultivating motivation in a one-sided manner can cause injury to a person's character.

I think that that's right.

But don't just take Charlotte's or my word for it — a few years ago, researchers did a study in which students were to agree or disagree with various statements about learning. The statements represented learning in various ways, including:

- Learning as gaining information

- Learning as remembering, using, and understanding information

- Learning as duty

- Learning as personal change

- Learning as process

- Learning as social competence

They looked for a correlation between student definitions of learning and student achievement. So which of the above was the best?

It wasn't any one of them; it was all of them. The more conceptions of learning students had, the more likely they were to succeed academically.

The point? When it comes to Value, we want to play toward as many angles as we can.

The best angle of all: learning is good because learning is good

In my observations of students and how they are best motivated, I find that the absolute holy grail Value belief situation is when a student believes that even learning that they won't need someday is still worth doing because learning is beautiful and fun and interesting and hard and worthy and emancipatory. Basically: learning is good because learning is good.

Here's a little clip where a student letter I received last year indicates that she's discovering this truth for herself:

And here's a video where I go further in to what I see as the most under-played approach to Value in American education today.

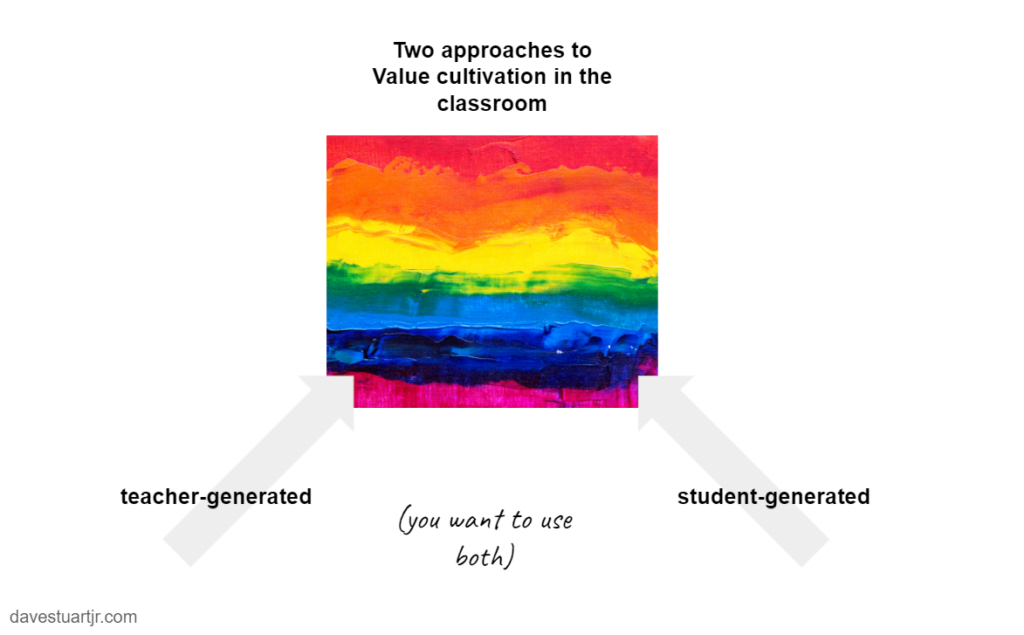

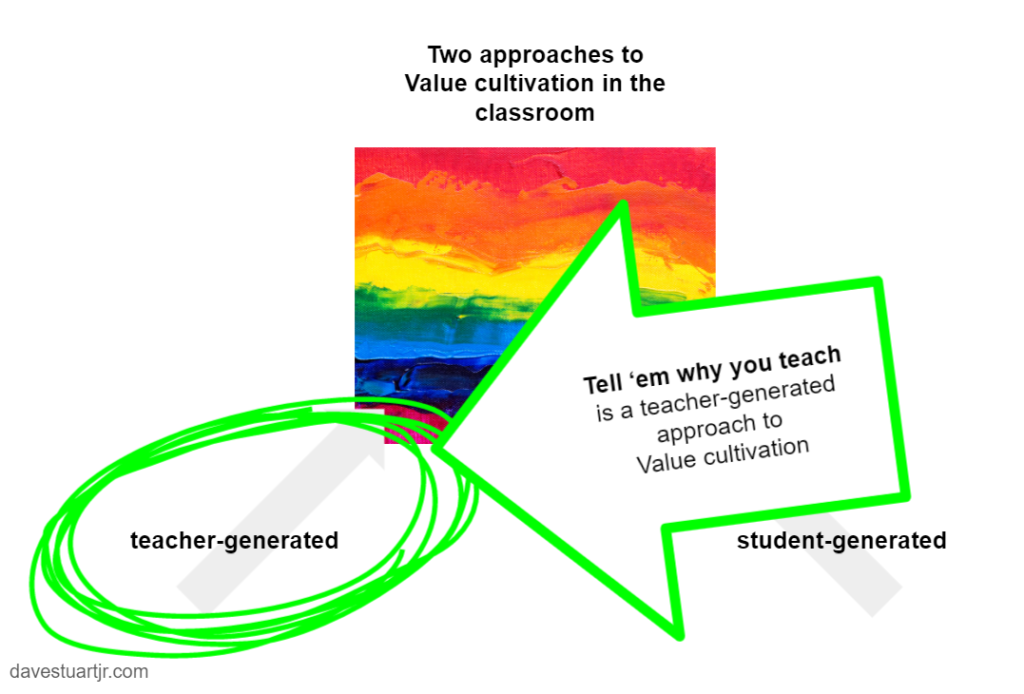

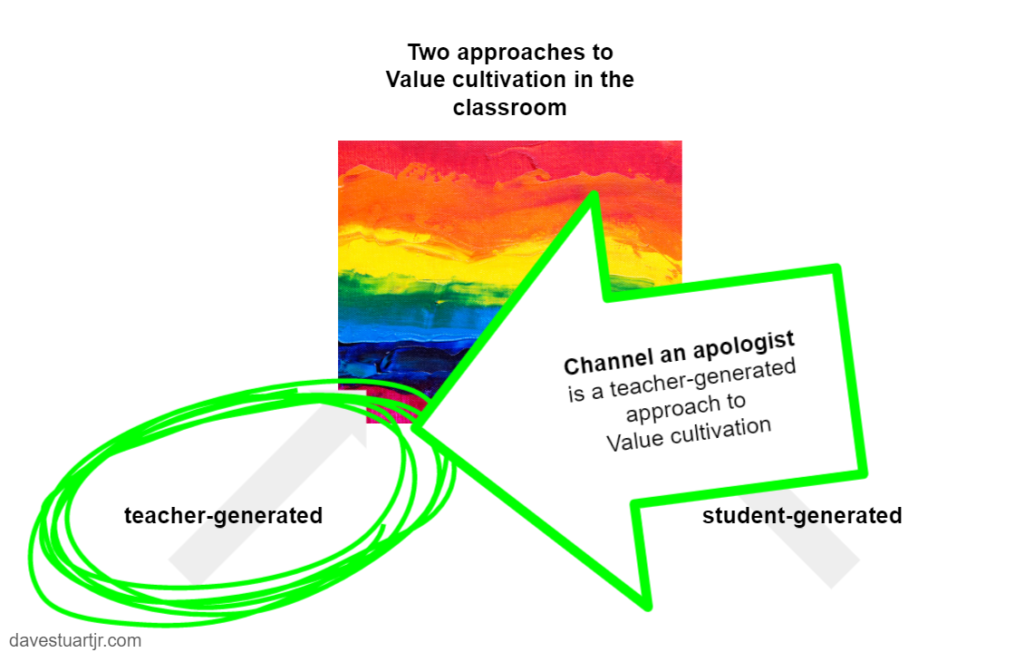

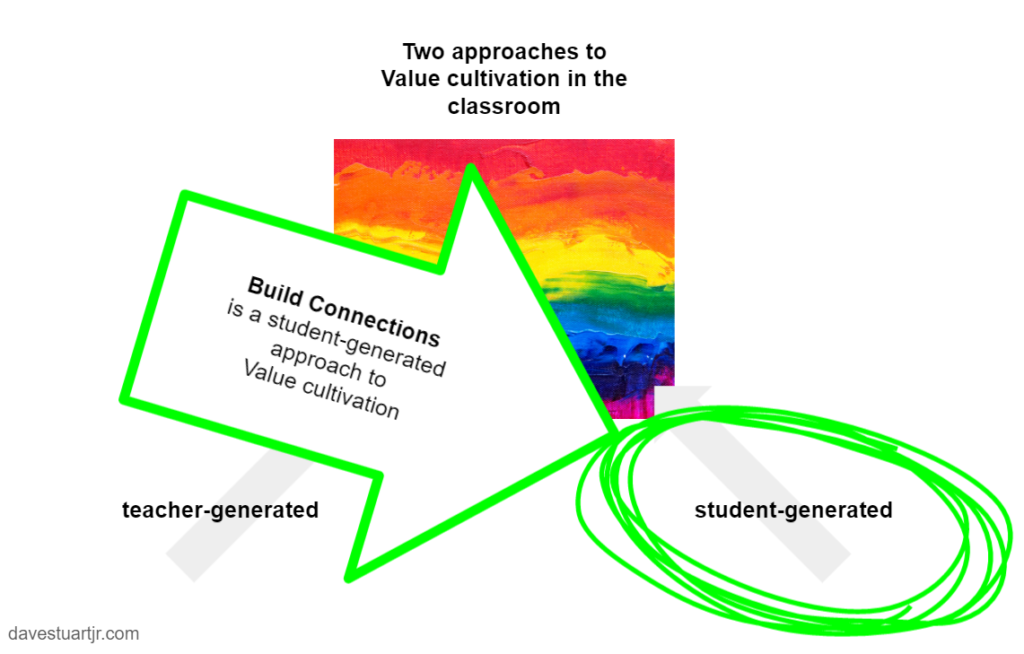

Two approaches to Value cultivation: teacher- and student-generated

Here's the last thing I'll say before we get into the strategies. I like to think of effective Value cultivation efforts as two-pronged. There's the prong where I directly attempt to help my students to value the mastery work we're doing, and then there's the prong where I help them find their own value paths to the work at hand. Both are powerful in different ways.

And that's plenty to bring us to our practical considerations for the first few weeks of school. What are three surefire ways to cultivate Value in your setting during the first weeks of school?

II. The Three Best Methods for Cultivating Value in the First Weeks of School

So you know me: picky about my strategies. I want as much good as possible to come from the efforts I take as a teacher. There are millions of ways to cultivate Value in a classroom, but tons of them require prep or money or time or complexity that I can't afford.

So with simplicity and robustness in view, here are the three strategies I lean on most during the first weeks of school.

Strategy #1: Tell 'em why you teach.

When a young person has a strong sense of purpose — “a long-term goal to accomplish something meaningful to the self” — and sees a link between that purpose and whatever lesson you're currently teaching, Value is in full power. Those word we started this article with — boring, stupid, and so on — don't apply to work that's clearly linked to one's purpose. Such work becomes necessary and meaningful — and as a result, the student writes the words or works the problems or asks the questions or reads the articles.

Purpose, then, is a power path into the Value belief.

Thankfully, Stanford professor Bill Damon and his team have spent the past 15 years studying the development of purpose in young people. Damon's book shares the team's findings in depth, and this article by Damon does a good job giving an overview. (I'd recommend the article as a warm-up read at your next staff meeting; this article is also where the quotations in my blog post today come from.)

Damon recommends this: once per year, tell your students why you chose teaching as a profession, what you find fulfilling about teaching, and what you hope to accomplish with your students. In other words: spend five minutes showing your kids “what it looks like for an admired adult to pursue a vocation with purpose.”

Don't miss that last part. You're not trying to sell them on teaching; instead, you're just modeling purpose.

And I say do this once a month, not once a year. It's cheap in terms of your effort and the class' time, but the potential downstream benefits are massive.

Here's an example of me communicating why I became a teacher to my students.

Encountering “purpose exemplars” is one of the key means for building purpose in young people — so, start with yourself.

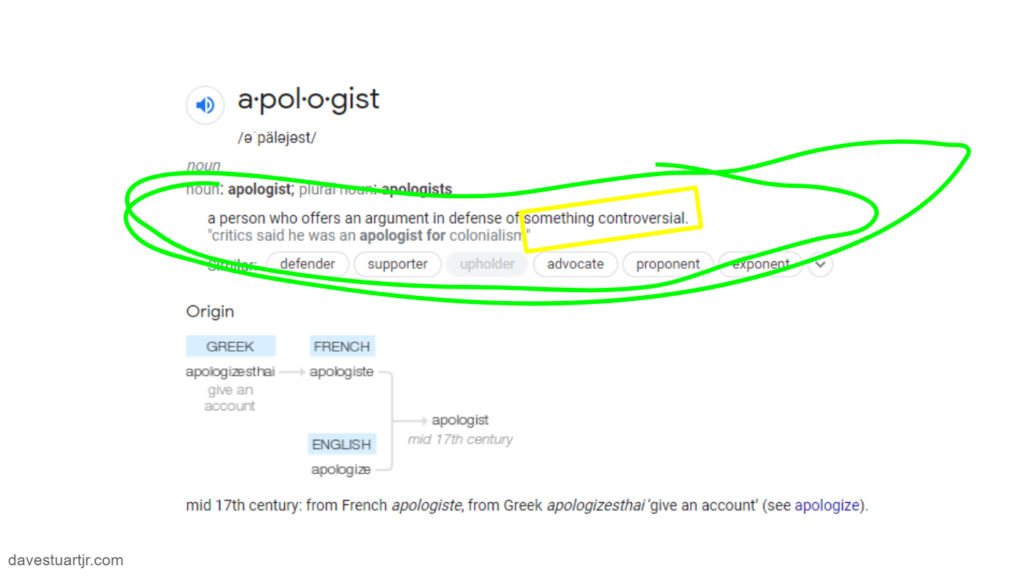

Strategy #2: Channel an apologist.

Now apologizing isn't too common an idea nowadays, is it? Admitting wrong and telling folks about it — that's just not something we often see modeled for us, despite the great utility of apology to a well-lived life.

But that common definition of apology isn't what I want you to channel to cultivate the Value belief in your classroom. Nope.

Instead, I want you to channel the energies of an apologist. Take a look at what I mean:

My friend, you and I, every single day of our teaching careers, represent something that is controversial — or heck, it's even past controversial. It's just a dead issue — most folks don't even think about.

The dead idea? That learning is good because learning is good. That it's not primarily about the utility of your algebra class, or the relevance of your physics lesson, or the fun factor of your world history unit. Nope — what it's about is the uniquely human capacity for pursuing mastery. Mastery is rewarding, fulfilling, emancipatory, amazing, beautiful, and good. For all of us.

No one's ever been smaller for having learned about the things you're trying to teach this school year. No one. Your discipline offers lessons and insights that expand us, give us new eyes, gift us with previously inaccessible ways of interpreting or understanding the big ol' complex world and universe we live in. That's what you're doing when you teach reading or writing or literature or world languages. You're offering a new kind of existence.

So the main idea here is that I want you and me to be the C. S. Lewises of this unpopular, barely thought of idea — this idea that what's on offer in your class is the good stuff. And I say C. S. Lewis on purpose because his apologetic approach was gentle, winsome, respectful, earthy, and imaginative. For Lewis, arguing for a controversial idea — in his case, Christianity during the advent of post-modernism — wasn't a chore to be done or a war to be won. For Lewis, it was a set of pleasures, a series of puzzles. He approached apologetics like an artist and an engineer and a storyteller and a next door neighbor.

That's what I'm saying you can do, from day one, in your classroom.

A few pointers for speeding up your apologetics:

These things will help you to become better quickly in your apologetics for learning:

- Remember that it's fun. It's playful.

- Remember that every class offered in your school helps young people toward long-term flourishing. There's no scarcity with the Value belief. We want our students to value all of their classes. So I say this: avoid any kind of apologetic that makes your discipline shine at the expense of another.

- Ask colleagues to share their approaches. I like to ask people things like, “What's a lesson or type of practice that you ask students to do that they initially find boring or unenjoyable or onerous? How do you ‘make the case' for the task anyways? Why is this task critical to growing in mastery in your discipline?” This line of questioning lets me learn from colleagues' apologetic approaches, and that's always fun. It also helps my colleagues and me make sure that we're never assigning boring or unenjoyable or onerous tasks needlessly. (If a task doesn't help toward mastery, it should not be assigned.)

- Tell stories and use analogies. It's not all about evidence and logic.

- You're making an argument, but you're doing it amicably. Read more about my classroom argumentation philosophy here.

How to apply this to the first weeks of school

For each assignment type you introduce to students, make its case. For example, when I introduce article of the week or pop-up debate to my students, I do so partly from the stance of an apologist. I want my students to understand that all the work we do together is aimed at mastery; none of it is busywork.

Strategy #3: At the end of Week 3, try Chris Hulleman's Build Connections intervention.

Some years back, UVA researcher Chris Hulleman was a part of a series of studies that were interested in helping secondary and post-secondary science students with low “expectancy-value” — they didn't expect to get much from science and didn't particularly care — to find greater motivation in class. They developed an intervention that basically goes like this.

- Step 1: Students brainstorm a list of things they personally value: aspirations, interests, hobbies, relationships.

- Step 2: Students brainstorm a list of things they've learned or practiced recently in class — assignments, skills, knowledge, concepts, projects.

- Step 3: Students draw lines between their two lists — seeking any connection between their own values and what they are learning.

- Step 4: Students write about one of their connections:

- “[Item in List A] connects to [Item in List B] because _____________.”

- “[Item in List B] could be important to my life because ___________.”

That's it.

This intervention took place about once per month. Students with low expectancy-value who received the intervention were significantly more likely to elect science classes in the future and to express an interest in science-related fields. They also tended to have higher science GPAs than their peers in the control group.

(Want to see a video of me conducting this intervention with my own students? Coming this fall — subscribe to the YouTube channel to be sure you don't miss it.)

Help with getting started with this “Build Connections” intervention

Of the three strategies I've shared here, this Build Connections intervention definitely takes the most practice to get good at. To help you with that, try these dig deeper resources:

- Simple Interventions: Building Connections to Help Kids Value Coursework

- Small Tweaks for Making Chris Hulleman’s Build Connections Intervention Work Even Better

- Character Lab's Build Connections page (includes a reproducible PDF to use with students)

- Chris Hulleman's Motivate Lab homepage (use this to access Hulleman's bibliography)

These three will work

In these five key beliefs guides, I'm not aiming at an exhaustive list of strategies. You don't need that. That'll be overwhelming.

Instead, today I shared what I see as the top three strategies for cultivating Value in your classroom. These are particularly helpful in the first weeks of school, but they'll also work at all other points in the year. I use each of them regularly. I hope they help you as much as they do me.

The Footnote

[1] As we discussed in this article, beliefs are knowledge held in the will — meaning they are not necessarily things that we think about or articulate. So when I say, “Sounds like,” I'm not speaking literally.

Leave a Reply