Teacher Credibility is one of five key beliefs beneath student motivation, and it is a uniquely powerful force in a classroom. From a position of Credibility, a teacher has leverage for cultivating student beliefs in Value, Belonging, Effort, and Efficacy. But from a position of anti-Credibility, a teacher will have a hard time influencing these other things.

Did you miss the intro series? It covers important territory for maximizing the five key beliefs in your school and classroom. Take a look.

- Part 1: On the Teaching of Souls

- Part 2: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Part 3: Five Critical Qualities about the Five Key Beliefs, in Order of Actionability

Never miss an article again! Subscribe to Dave's weekly newsletter, and be the cool colleague forwarding sweet articles to the team.

Because of this, it's helpful to think of Credibility as the “one belief to rule them all.” Or as the root of the belief mountain.

In this article, let's look at two things:

- I. Important Characteristics of the Credibility Belief

- II. Three Strategies for Cultivating Credibility in the Classroom

I. Important Characteristics of the Credibility Belief

Let's get clear on what we're after.

What it sounds like in the heart of a student [1]

- My teacher is good at her job.

- He knows what he is doing.

- She can make a difference for me.

- He cares about me as a person and a learner.

- She likes her job.

What Credibility is

I love Credibility because it sounds too good to be true. You're telling me that if students believe that I'm a good teacher, then they'll progress more while they're in my class?

Yes — that is what I'm saying. But don't take my word for it.

Featured prominently in research

In the largest meta-analysis in the history of educational research, Dr. John Hattie and his team calculate teacher Credibility at more than twice the effect size of a standard classroom influence (e.g., see p. 66 of Fisher, Frey, and Hattie's recent Distance Learning Playbook). In an earlier book, Hattie, Fisher, and Frey go so far as to claim that “the dynamic of teacher credibility is always at play” (p. 10 of this book).

The reason I bring up those folks is simple: I want you to realize that the profoundly simplistic idea of Credibility — if a child believes you can make a difference for them as their teacher, then you will make a difference for them as their teacher — is built on some firm rock.

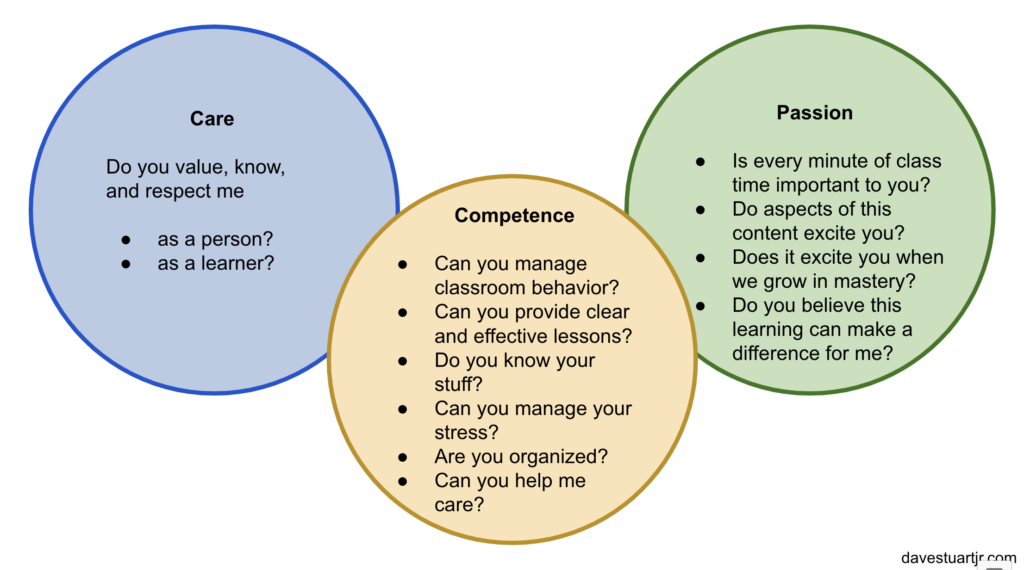

Built student perceptions of CCP — Care, Competence, Passion

There are other constructs for thinking about Credibility's components — e.g., Trust, Competence, Dynamism, and Immediacy in this book — but the one I use is the simplest: CCP. Care, Competence, Passion.

When a student sees consistent signals from you — words, actions — that you care about them (Care), that you know what you're doing (Competence), and that you like what you're doing (Passion), then guess what? They'll probably believe that you're credible.

Undermined by certain teacher misbehavior types

There's this fascinating study where researchers looked at the effects of teacher misbehaviors on teacher credibility in college classrooms. They grouped the misbehaviors into three categories:

- Indolence — arriving late, forgetting test dates, neglecting grading, returning papers late, making class too easy, constantly changing assignments

- Incompetence — presenting poor instructions, making tests too hard, overloading students with information, being boring, mispronouncing words, failing to manage the classroom

- Offensiveness — humiliating students, playing favorites, acting rude, being verbally abusive, making arbitrary decisions

The study found that all misbehavior types harmed teacher credibility but that offensive misbehaviors had the most severe effects.

- The bad news here is that in a given school year, you're going to make some of these mistakes, simply as a byproduct of how complex a classroom is.

- The good news, though, is that Credibility is malleable. Once we know how it works, we can make repairs quite efficiently.

What Credibility isn't

To help us think clearly about this belief, we've got to make sure we avoid common misperceptions.

Misperception 1: If I'm not a student's favorite then I'm not Credible.

One thing I love about Credibility is that there is no scarcity to it. Every teacher in a hallway, in a building, in a s

One thing I love about Credibility is that there is no scarcity to it. Every teacher in a hallway, in a building, in a district, and in the world can be Credible. Each student can have a teacher they believe in.

You and I don't need to compete for Credibility. And in fact, we actually want to help each other grow more Credible because your credibility, as a representative of the school, helps mine as the same.

Meanwhile, teacher popularity or “You're my favorite teacher” compliments are fundamentally built on competition and scarcity. They're about getting the kids to pick ME over YOU. Chasing after that kind of thing, whew! It can sap your soul. I've seen it in myself, and I've seen it in others.

Credibility, thank goodness, doesn't get us going after any of that.

Misperception 2: It all happens in the first week of school. If you mess up there, you're done for.

There's lots of hype around the first days of school, as well there ought to be. You don't get a second chance at a first impression, right?

But the good news with Credibility is that it's a long-term game. No matter how your first week goes, or your next week, or the week after that, what matters most is: How am I going to signal to my students that I am Credible today? How can I signal Care, and/or Competence, and/or Passion to the individuals I teach right now?

In other words, while it's true that first days have special characteristics in the hearts of our students, it's mostly in the humdrum other 179 where Credibility is made or lost.

Misperception 3: If only a few of my students like me, then I'm a Credible teacher.

There are a pair of problems with the idea expressed above.

First of all, Credibility isn't about being liked; it's about being judged as good at your job, being judged as someone who can take your students to someplace good that in their hearts they yearn to go. (And yes, high school teachers — our students' hearts are yearning just as strongly as a five year old beneath those too-cool-for-school veneers!)

It certainly helps to be liked by your students — so long as that being liked doesn't hijack your ego. But, it's not necessarily required. What we're after is something more nuanced than that. Something deeper and stronger and more educationally impactful.

And secondly, teacher Credibility is something we're responsible for trying to cultivate in the hearts of each one of our students — not just the students we have the easiest time gaining rapport with. We can't be satisfied with signaling just to the nice kids or the nerdy kids or the athletic kids or the artsy kids that we care about them — we have to signal this to ALL of them.

II. The Three Best Methods for Cultivating Credibility in the First Weeks of School

I'm picky about my strategies. If they take a ton of extra effort, I'm not interested. If they require a ton of time outside of class, I'm also not interested. If they take a ton of class time away from mastery-building work… you get the idea.

I'm after stuff that gives a big bang for the buck. Small efforts, big results.

(Back in the day, I didn't have this pickiness, and it cost me my job.)

Here are three interventions for cultivating Credibility in the first weeks of school. If you've been reading my work for awhile, these are going to look familiar. That's good news — it means I'm doing my job. 🙂

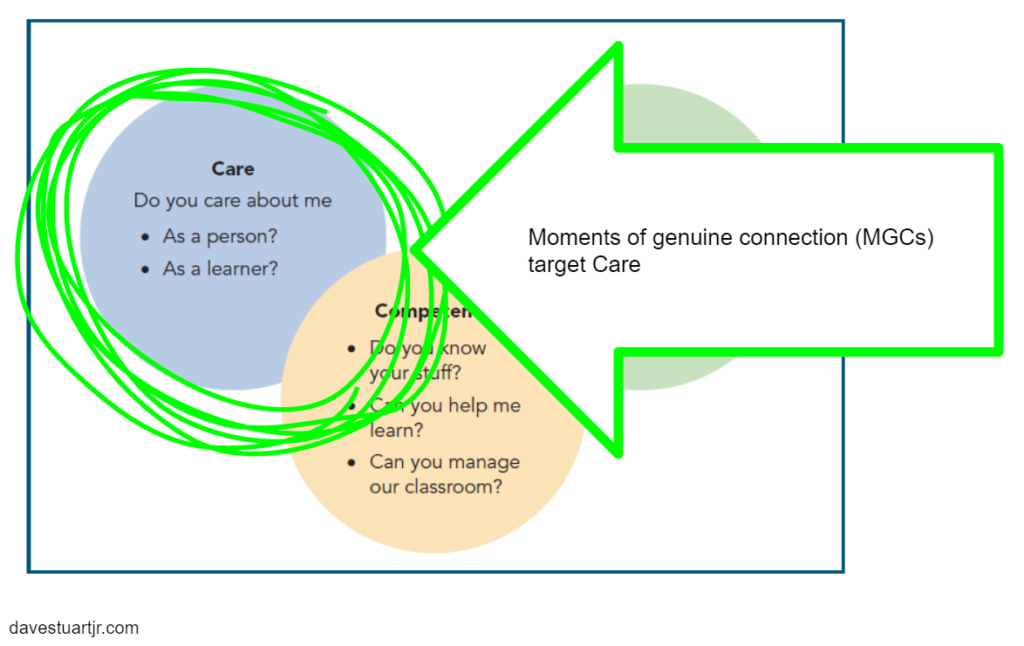

Strategy #1: Track moments of genuine connection.

Tracking moments of genuine connection is probably my most thoroughly unoriginal idea, which is truly amazing because I'm proud of how unoriginal my ideas typically are.

It's something we all do, except for the track part. And the tracking part is where the compounding power comes in.

It's all in the name

This strategy is simple:

- Track — you put all your rosters on a single sheet of paper (I copy and paste into a simple spreadsheet for this), you print out a dozen or so of these sheets of paper, you put 'em on a clipboard, and every time that you attempt an MGC you make a record of it on the clipboard. (A record of it for me = a checkmark, or a P for Personal/A for academic, or a single word summary of what we chatted about.)

- Moments — these are brief, as in 30 to 90 seconds. They are embedded in your normal working hours — meaning, right before class starts I try an MGC or two, right after the bell rings I try one or two, and maybe for a few minutes during an independent practice portion of my lessons I'll try one or two. The idea here is that I don't place relationship-building into the times in my day meant for depressurization (lunch) or productivity (e.g., prep period) or creativity (e.g., after school). I used to have my door open all the time — all loving teachers are supposed to do that, right? — but I found that I was not improving in anything but relationship-building. And relationships aren't the point of school. They're a great reward of school and a great tool for teachers, but they're not the aim.

- of Genuine Connection — what you're trying to do in these moments is to make a student feel valued, known, or respected. Those three words aren't ones I made up — they're all throughout the research on Belonging. So what you're attempting to do in these moments is to make a student feel those ways. Now, some quick notes that help a lot in making this work:

- Balance academic and personal — Sometimes, you want to communicate that you value, know, or respect a student personally, and sometimes you want to communicate that you value, know, or respect a student academically. Many good-intentioned educators make the mistake of only focusing on personal connection — I was like this in my early career. The problem with this is that you're at risk of confusing Credibility with Likeability — and they're not the same thing. It's possible for students to believe that we're nice people and to believe that we're not that good at teaching. We don't want that.

- It's gotta be genuine — If you don't want to waste your time with MGCs, start getting in the habit of working internally on difficulties that you have with liking your students. And, friend, listen — we all have those struggles. A student annoys us, or offends us, or makes us feel disrespected, or causes us grief. These things come with being in relationship with other human beings. What you and I have to do in these cases is get good at examining our hearts for problems and processing them through to resolution. Bonus benefit: when we do this, we grow more emotionally and socially mature.

- All you can do is attempt it — A cool thing about people is how complex and autonomous we are. You and I can never guarantee that a student will feel valued, known, or respected in a given encounter. All we can do is attempt. This is why it's important to keep doing MGCs all year long, filling that clipboard before moving to a fresh page. That way you're getting a decent volume of MGCs for each student, thereby increasing the odds that some of the attempts will really connect.

Works so good that it's dumb

That's what my buddy Eddie Johns said one time in a team meeting when we were talking about MGCs. I considered it a wonderful compliment. MGCs: the dumbest intervention ever.

Also, some schools I've worked with have implemented MGCs at the whole-school level. Talk about power!

Dig deeper into moments of genuine connection

- This is a podcast interview I did with Jenn Gonzalez over at Cult of Pedagogy. It's all about MGCs.

- This is a video I did regarding MGCs once upon a time. (BTW, I've got short videos posting on YouTube 2x/week now — subscribe here so that you don't have to remind yourself to check out the latest.)

- I've got a list of ten or so sample MGCs on p. 30-31 of These 6 Things. Bunch of ordering options for the book right here; if you get a copy for yourself or your team, dog-ear Chapter 2 because it's all about the five key beliefs.

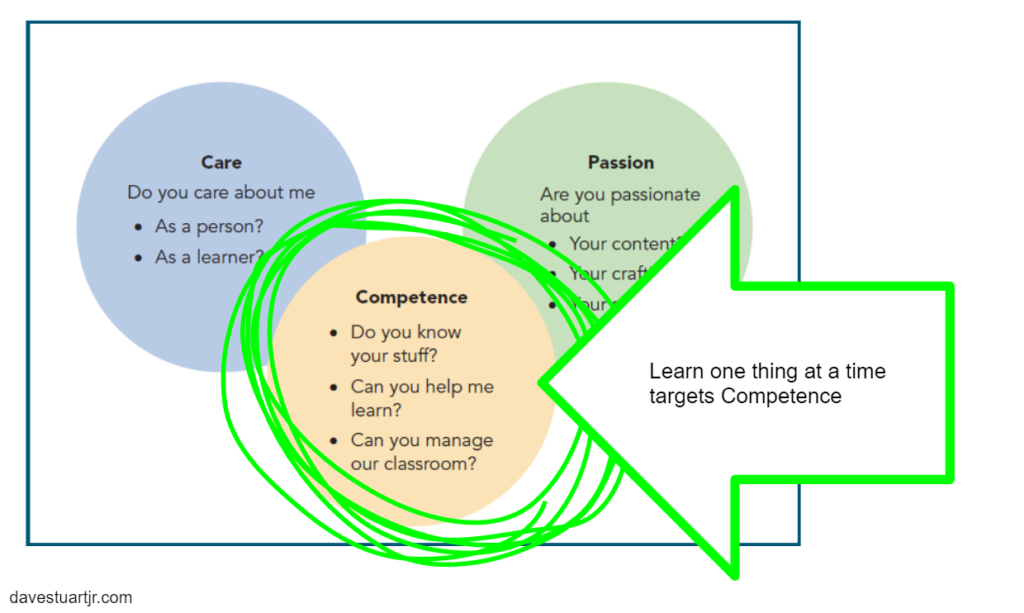

Strategy #2: Learn one thing at a time.

Now let's talk about Competence. This is where I (fail to) give you the lightning-fast method for developing Competence as a teacher.

Here's the deal: unlike with Care, there's really not a fast intervention for getting better at teaching. The stuff that goes into competence — adjusting instruction on the fly, meeting the diverse needs of learners, understanding and acting on principles of learning or motivation, managing a classroom — this is the stuff of expertise, and expertise is won through persistent and deliberate practice.

But if there's a shortcut to competence, it's this

I can still remember when I first became aware that there were thousands of trade books about teaching. Discovering teacher-writers like Jim Burke, Penny Kittle, Carol Jago, Kelly Gallagher, Gerald Graff, Cathy Birkenstein, Mike Schmoker — it was a total thrill, and I read these things like a maniac.

The trouble was that I was always trying something new, chasing the latest strategy I had heard about, doing tons of one-off prep work.

I was unfocused.

Finally, I had had enough, and I decided to read only one book for an entire year. It was Mike Schmoker's Focus. My copy is ragged today, and there's not a thing in the book that I didn't work at repeatedly for that one year of my teaching.

Two positive things happened as a result of this:

- I enjoyed my job more and was less stressed.

- I got better at my job.

How to apply this to the first weeks of school

Basically, pick one thing you'd like to get better at as a teacher in the next few weeks and only invest professional learning energy into improving at that one thing.

If you're new in your career, I recommend fundamentals:

- Classroom management (here's a post where I collected a bajillion mini-articles that helped me years ago; here's a course I published with pro teacher Lynsay Mills Fabio);

- Student motivation (I'm working to make my blog a go-to spot for you on this; you can start by doing a Ctl+F search for the term “key beliefs” on this page; here's a course I published that comprehensively explores the five key beliefs).

More established? Try argumentation, or knowledge-building, or reading, or writing, or speaking/listening. I spend a chapter on each of those These 6 Things. Basically, that book is the fruit of my year of extended meditation on Schmoker.

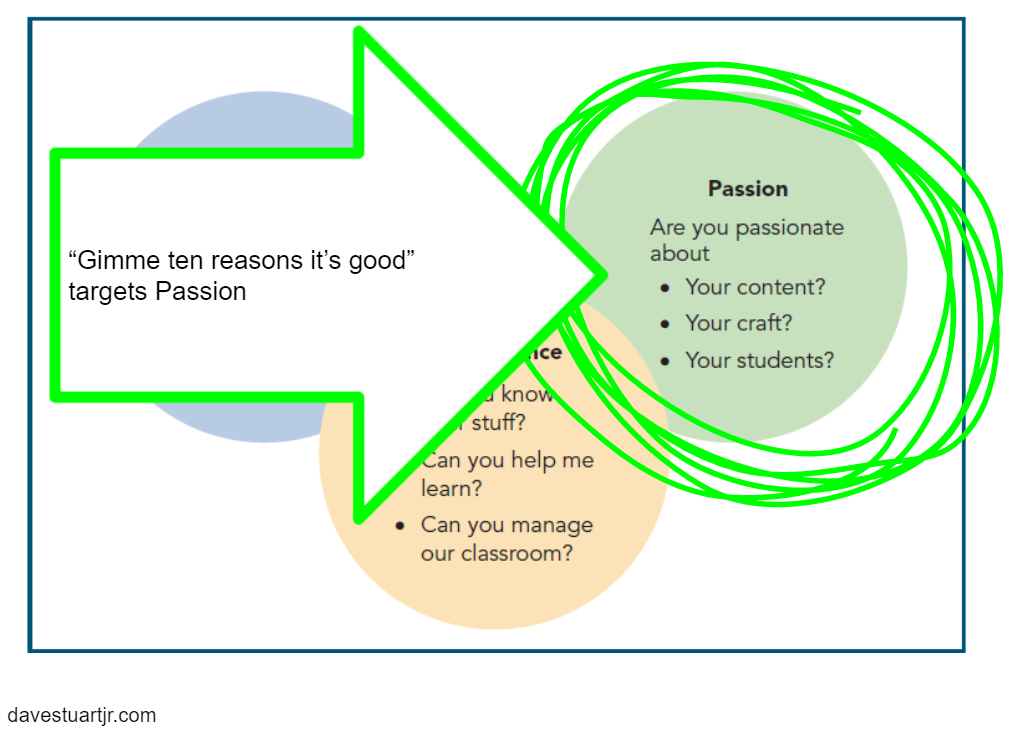

Strategy #3: Gimme ten reasons it's good

From what I can tell, there are three avenues into passion for a given lesson or unit or course.

- Passion about the content

- Passion about your students

- Passion about the craft of connecting #1 to #2

Ideally, you and I would have each of those maxed out at all times. Every lesson, every assignment, and every unit would be like Christmas morning.

Alas, it is often not so. And alas, I must now horrify many of my fellow English teachers by telling about how I don't much like Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451.

How to have passion for teaching a unit you really don't like

So look — maybe you're a science teacher who gets bored by photosynthesis, or an art teacher who dislikes watercolor, or a math teacher who is annoyed by quadratic equations. I don't know what your guilty passion pothole is, but one of mine is Fahrenheit 451.

It's not the plot. It's not the characters. It's not the premise.

It's the writing. The book feels to me like Bradbury was getting paid per stylistic twist. On the very first page, we've got:

- Things getting eaten

- A great python

- Venomous kerosene

- A conductor playing symphonies

- Charcoal ruins of history

- A symbolic helmet numbered 451

- The word stolid

- A jumping house

- Fireflies

- Marshmallows

- Flapping pigeon-winged books

It's just all a bit on the nose for me. That's all.

And the reason I bring it up is not so that you'll question yourself for ever trusting me (folks who don't teach English, believe me — some folks are deeply horrified right now), but rather to say that despite my stylistic complaints with this book, I still am passionate about the F451 unit in our curriculum.

Why? Because it's all kinds of good! Here are ten quick reasons:

- After I surface my complaint with Bradbury's style, a portion of students end up opposing my view and a good-natured argument develops over the whole course of our reading.

- I love the pop-up debate we have about whether our society is really becoming like Bradbury's dystopia. [2]

- Sometimes the descriptions delight me despite myself. (E.g., Beatty's end.)

- I get to model for my students the value (and joy) of doing work that we don't 100% want to do. This open-mindedness is contagious.

- I like comparing with students Bradbury's description of schooling and the schooling they experience.

- I like comparing with students how Bradbury depicts voter decision-making and what they've observed.

- I like the new words we get to play around with because of Bradbury. (E.g., stolid.)

- I like being able to reference F451 for the rest of the school year as a shared part of our class culture.

- I like asking students to bring in questions from their reading and placing them into Conversation Challenge groups where they aim to collectively put to rest as may questions as possible. [3]

- I like how it feels to have a good time teaching something that I don't one hundred percent love.

I could go on! But the point isn't my list — it's yours.

The best way to cultivate a resilient passion for your work is to “gimme ten reasons it's good”

You can make lists of ten for teaching in general, for specific assignments, for units or books or topics, for specific class periods — do it wherever you need a passion pump-up.

But Dave, what if the unit/lesson/course is just legitimately NOT good?

Advocate for change on your own time, but in the meantime, with these students in this class right now, you want to cultivate in yourself a fire for doing right by them.

These three will work

This isn't an exhaustive list by design. Instead, it's me picking the top three strategies for cultivating Credibility in your classroom. These are particularly helpful in the first weeks of school, but they'll also work at all other points in the year. I use each of them regularly. I hope they help you as much as they do me.

The Footnotes

[1] As we discussed in this article, beliefs are knowledge held in the will — meaning they are not necessarily things that we think about or articulate.

[2] I discuss pop-up debates in-depth in Chapter 4 of These 6 Things.

[3] I discuss conversation challenge in-depth in These 6 Things.

Jim Woehrle says

Dave, I could go in-depth on what this has meant for me, but I’ll try to keep it succinct. Few things have changed my practice and instruction over the past few years like the concept of MGCs. Sometimes I use a clipboard, other times a mental note. They’re generally quick, easy to do and pretty darn fun. This is especially true when I find out what kids are passionate about and sort of play dumb/naive/ignorant when I ask them about it. “So…what’s it like to be a really great soccer player? What do you think the Spartans’ chances are this weekend? How’s play practice going these days…everyone off-book yet?” Big payoffs for such a seemingly easy investment.

I once did an experiment where I made a deliberate effort at MGCs in one class and kept it pretty close to the vest with the same course in a different period. It was only for a week and nothing so dramatic as a “good cop/bad cop” or Jekyll/Hyde dichotomy. Just a slight change in my behavior for a few days. Not only did it make a difference in the level of motivation for the students, I also noticed a huge difference in my own level of energy and motivation.

This is powerful stuff, Dave, and I thank you for it immensely.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Jim, thank you for this — this is gold!

Jacob Patrick OConnor says

There is a lot of really helpful information in this blog, and I wanted to thank you for it. I am currently a student teacher. One of my professors, towards the beginning of my program, told my cohort that we shouldn’t use please or thank you when talking to students. The reasoning was that if we are asking or thanking a student for meeting classroom expectations that using those words suggests to them that their behavior wasn’t necessary or required of them. In terms of establishing care with students, to build credibility, what is your opinion on this? I am still new to navigating a classroom environment and would appreciate any insight that an expert such as yourself might have.

Thank you.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Jacob, tell your UM professor that I’d love to come visit the class someday if they are game. I’m just across the state and UM is my alma mater. I’ve always wanted to come back. Take care.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

Also Jacob, so sorry to miss your question! I can see your professor’s point, and when I think on my own interactions with students I do find that I use “thank you” and “please” pretty infrequently when giving instructions. Instead of thank you, I tend to give feedback — “Yes, that’s great”; “Oops, a bit quieter, we need it to help us think”; etc.

sky says

Hi Jacob!

I wonder if you kept this up…

Personally, I’m happy to use “please” and “thank you” in my classroom. I use polite speech with students just as I do with my family. It may be someone’s turn to do the dishes (“meeting expectations”), but I try to express my appreciation, especially when they do their task with a cheerful attitude (but even if they don’t). 😉